Miami Surface Shuttle Services: Feasibility Study for Transit Circulator Services in Downtown Miami, Brickell, Overtown, and Ai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Demand Model

TECHNICAL REPORT 6 TRAVEL DEMAND MODEL SEPTEMBER 2019 0 TECHINCAL REPORT 6 TRAVEL DEMAND MODEL This document was prepared by the Miami-Dade Transportation Planning Organization (TPO) in collaboration with the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) District Six, Miami- Dade Expressway Authority (MDX), Florida’s Turnpike Enterprise (FTE), South Florida Regional Transportation Authority (SFRTA), Miami-Dade Department of Transportation and Public Works (DTPW), Miami-Dade Regulatory and Economic Resources (RER) Department, Miami- Dade Aviation Department (MDAD), Miami-Dade Seaport Department, Miami-Dade County Office of Strategic Business Management, City of North Miami, City of Hialeah, City of Miami, City of Miami Beach, City of Miami Gardens, City of Homestead, Miami-Dade County Public Schools, Miami-Dade TPO Citizens’ Transportation Advisory Committee (CTAC), Miami-Dade TPO Bicycle/ Pedestrian Advisory Committee (BPAC), Miami-Dade TPO Freight Transportation Advisory Committee (FTAC), Transportation Aesthetics Review Committee (TARC), Broward County Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), Palm Beach County Transportation Planning Agency (TPA), and the South Florida Regional Planning Council (SFRPC). The Miami-Dade TPO complies with the provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which states: No person in the United States shall, on grounds of race, color,or national origin, be excluded from participating in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. It is also the policy of the Miami-Dade TPO to comply with all the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). For materials in accessible format please call (305) 375-4507. The preparation of this report has been financed in part from the U.S. -

Martin-Vilato Associates, Inc. Consulting Engineers

MARTIN-VILATO ASSOCIATES, INC. Consulting Engineers 2730 S.W. 3rd. AVE., SUITE 402, MIAMI, FL. 33129 PRINCIPALS: Ricardo A. Martín, P.E., President Mechanical Engineer Enrique G. Vilató, P.E., Vice-President Electrical Engineer HISTORY: Martin-Vilato Associates, Inc. was founded in 1981 for the purpose of providing combined mechanical and electrical consulting engineering services to architects, interior designers, developers, and government agencies. The principals have extensive experience in their own fields and are ready to assist their clients from planning to final design and construction. We presently have projects under design or construction all over South Florida. Throughout the years, we have designed projects all over the U.S. and overseas. The firm is fully covered with professional liability and commercial insurance. We are continuously expanding our design capabilities through the use of our computers for lighting design, economic analysis, and energy calculations, as well as for CAD applications At present, the firm employs the services of five engineers, designers, and CAD operators. In 1996, the firm received the “Outstanding Consulting Engineer of the Year” Award issued by the American Institute of Architects (AIA), Miami Chapter. RICARDO A. MARTIN, P.E. Education: B.S.M.E. - University of Florida, March 1971 Registration: Florida, 1975 California, 1980 Texas, 1981 Georgia, 1981 New York, 1991 Colorado, 1995 Experience: For the past 47 years, Mr. Martin has been involved in the mechanical design of a variety of large industrial, commercial, and residential projects including manufacturing facilities, solid waste transfer stations, sewage and water treatment plants, rapid transit systems (under and above ground), airports, hospitals, office buildings, schools and universities, and high-rise apartment buildings; plus numerous other projects for private clients, for local, state and federal government, and for the military. -

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County : Tequesta

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County By ADAM G. ADAMS The great land boom in Florida was centered in 1925. Since that time much has been written about the more colorful participants in developments leading to the climax. John S. Collins, the Lummus brothers and Carl Fisher at Miami Beach and George E. Merrick at Coral Gables, have had much well deserved attention. Many others whose names were household words before and during the boom are now all but forgotten. This is an effort, necessarily limited, to give a brief description of the times and to recall the names of a few of those less prominent, withal important develop- ers of Dade County. It seems strange now that South Florida was so long in being discovered. The great migration westward which went on for most of the 19th Century in the United States had done little to change the Southeast. The cities along the coast, Charleston, Savannah, Jacksonville, Pensacola, Mobile and New Orleans were very old communities. They had been settled for a hundred years or more. These old communities were still struggling to overcome the domination of an economy controlled by the North. By the turn of the century Progressives were beginning to be heard, those who were rebelling against the alleged strangle hold the Corporations had on the People. This struggle was vehement in Florida, including Dade County. Florida had almost been forgotten since the Seminole Wars. There were no roads penetrating the 350 miles to Miami. All traffic was through Jacksonville, by rail or water. There resided the big merchants, the promi- nent lawyers and the ruling politicians. -

Everglades National Park and the Seminole Problem

EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK 21 7 Invaders and Swamps Large numbers of Americans began migrating into south Florida during the late nineteenth century after railroads had cut through the forests and wetlands below Lake Okeechobee. By the 1880s engineers and land developers began promoting drainage projects, convinced that technology could transform this water-sogged country into land suitable for agriculture. At the turn of the cen- EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK AND THE tury, steam shovels and dredges hissed and wheezed their way into the Ever- glades, bent on draining the Southeast's last wilderness. They were the latest of SEMlNOLE PROBLEM many intruders. Although Spanish explorers had arrived on the Florida coast early in the sixteenth century, Spain's imperial toehold never grew beyond a few fragile It seems we can't do anything but harm to those people even outposts. Inland remained mysterious, a cartographic void, El Laguno del Es- when we try to help them. pirito Santo. Following Spain, the British too had little success colonizing the -Old Man Temple, Key Largo, 1948 interior. After several centuries, all that Europeans had established were a few scattered coastal forts. Nonetheless, Europe's hand fell heavily through disease and warfare upon the aboriginal Xmucuan, Apalachee, and Calusa people. By 1700 the peninsula's interior and both coasts were almost devoid of Indians. Swollen by tropical rains and overflowing every summer for millennia, Lake The vacuum did not last long. Creeks from Georgia and Alabama soon Filtered Okeechobee releases a sheet of water that drains south over grass-covered marl into Florida's panhandle and beyond, occupying native hunting grounds. -

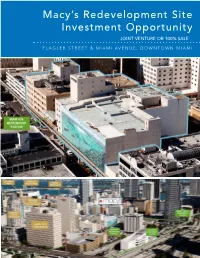

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Suniland Shopping Center 11293-11535 SOUTH DIXIE HWY, PINECREST, FL 33156

FOR LEASE > RETAIL SPACE Suniland Shopping Center 11293-11535 SOUTH DIXIE HWY, PINECREST, FL 33156 Property Features • High-traffic retail center located along Miami-Dade’s busiest and strongest retail corridor, US1 • Nestled between two upscale regional malls, Dadeland Mall & The Falls • Diverse range of shops and restaurants with strong sales • Trade area includes Pinecrest, Coral Gables & Kendall, where residents have an average HH income of $122k and average home values of $1.1M • + 83,500 vpd on US1 • + 11,200 vpd on SW 112th Street • GLA: 82,268 SF CONTACT: ARIEL BERNSTEIN CONTACT: STEVEN HENENFELD COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL 305 779 3152 305 779 3178 2121 Ponce de Leon Boulevard CORAL GABLES, FL CORAL GABLES, FL Suite 1250 [email protected] [email protected] Coral Gables, FL 33134 www.colliers.com SUNILAND SHOPPING CENTER > AREA RETAILERS SUNILAND SHOPPING CENTER > SITE PLAN SECOND FLOOR 11535A S T 11509 L I S E AUTO TAG A DENTIST , N W 1 11507 S 11349 11293A N BARBER SHOP ERN O D 11505 G O A BLOW SUSHIROCK M W DRY “BREEZEWAY” 11515 11521 “BREEZEWAY” FL COMMUNITY BANK 11327 11423-11427 11315 11325 11417 11421 11431 11429 11341 11399 11311 11331 11401 11403 200 11501 BOOKS & POP UP 11503 11355 11293 11297 11299 11301 U.S. HWY 1 / SOUTH DIXIE HIGHWAY - 94,100 VPD 100 11293A Auto Tag 1,651 SF 250 11403 Chicken Kitchen 1,330 SF 110 11293 Sushi Rock Cafe 2,426 SF 260 11415 Flanigans 8,250 SF 120 11297 Books & Books 2,320 SF 270 11417 European Wax Center 1,250 SF 130 11299 CVS Pharmacy 9,370 SF 280 11421 Piola 2,517 -

MDTA Metromover Extensions Transfer Analysis Final Technical Memorandum 3, April 1994

Center for Urban Transportation Research METRO-DADE TRANSIT AGENCY MDTA Metromover Extensions Transfer Analysis FINAL Technical Memorandum Number 3 Analysis of Impacts of Proposed Transfers Between Bus and Mover CUllR University of South Florida College of Engineering (Cf~-~- METRO-DADE TRANSIT AGENCY MDTA Metromover Extensions Transfer Analysis FINAL Technical Memorandum Number 3 Analysis of Impacts of Proposed Transfers Between Bus and Mover Prepared for Metro-Dade.. Transit Agency lft M E T R 0 D A D E 1 'I'··.·-.·.· ... .· ','··-,·.~ ... • R,,,.""' . ,~'.'~:; ·.... :.:~·-·· ,.,.,.,_, ,"\i :··-·· ".1 •... ,:~.: .. ::;·~·~·;;·'-_i; ·•· s· .,,.· - I ·1· Prepared by Center for Urban Transportation Research College of Engineering University of South Florida Tampa, Florida CUTR APRIL 1994 TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM NUMBER 3 Analysis of Impacts of Proposed Transfers between Bus and Mover Technical Memorandum Number 3 analyzes the impacts of the proposed transfers between Metrobus and the new legs of the Metromover scheduled to begin operation in late May 1994. Impacts on passengers walk distance from mover stations versus current bus stops, and station capacity will also be examined. STATION CAPACITY The following sections briefly describe the bus terminal/transfer locations for the Omni and Brickell Metromover Stations. Bus to mover transfers and bus route service levels are presented for each of the two Metromover stations. Figure 1 presents the Traffic Analysis Zones (TAZ) in the CBD, as well as a graphical representation of the Metromover alignment. Omni Station The Omni bus terminal adjacent to the Omni Metromover Station is scheduled to open along with the opening of the Metromover extensions in late May 1994. The Omni bus terminal/Metromover Station is bounded by Biscayne Boulevard, 14th Terrace, Bayshore Drive, and NE 15th Street. -

Wynwood BID Board of Directors Meeting Maps Backlot- 342 NW 24 St, Miami, FL 33127 June 3, 2021 from 11:15 A.M

Wynwood BID Board of Directors Meeting Maps Backlot- 342 NW 24 St, Miami, FL 33127 June 3, 2021 from 11:15 a.m. to 12:36 p.m. **Meeting Minutes are not verbatim** Board Members in Attendance: Albert Garcia, Wynwood BID Irving Lerner, Wynwood BID Marlo Courtney, Wynwood BID Bruce Fischman, Wynwood BID Glenn Orgin, Wynwood BID Gabriele Braha Izsak, Wynwood BID Sven Vogtland, Wynwood BID Jennifer Frehling, Wynwood BID Members Absent: Jon Paul Perez, Wynwood BID Others in Attendance: Pablo Velez, City of Miami City Attorney’s Office Krista Schmidt, City of Miami City Attorney’s Office Commander Daniel Kerr, City of Miami Police Department Taylor Cavazos, Kivvit PR Charles Rabin, Miami Herald Emily Michot, Miami Herald David Polinsky, Fortis Design + Build Elias Mitrani David Lerner, Lerner Family Properties Jonathan Treysten, More Development Robin Alonso, Tricap Andy Charry, Metro 1 Bhavin Dhupelia, Rupees Sachin Dhupelia, Rupees Yircary Caraballo, Arcade1up Eric Mclutchleon, Arcade1up Sarah Porter, Swarm Inc. Christina Gonzalez, Swarm Inc. Henry Bedoya, Dogfish Head Miami Alan Ket, Museum of Graffiti Manny Gonzalez, Wynwood BID Aleksander Sanchez, Wynwood BID Christopher Hoffman, Wynwood BID 1 Wynwood Business Improvement District (BID) Chairman, Albert Garcia, called the meeting to order at 11:15am. PUBLIC COMMENTS: At commencement of the meeting, Albert Garcia opened the public comments portion for the BID Board of Director’s meeting. It was noted that there were no Public Comments. Albert Garcia closed the public comments portion of the BID Board of Director’s meeting. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR REPORT: Wynwood BID Executive Director, Manny Gonzalez, provided an update on the Wynwood Security Network. -

Nordstrom to Open at Turnberry's Aventura Mall in South Florida

Nordstrom to Open at Turnberry's Aventura Mall in South Florida July 7, 2005 SEATTLE, July 7, 2005 /PRNewswire-FirstCall via COMTEX/ -- Seattle-based Nordstrom, Inc. (NYSE: JWN), a leading fashion specialty retailer announced it has signed a letter of intent with Turnberry Associates and the Simon Property Group, Inc. to open a new Nordstrom store at Aventura Mall in South Florida. Nordstrom will build a new, two-level store that will be approximately 167,000 square feet. The store will be attached to existing space that will be renovated to include eight to 10 additional retailers. A parking deck will also be created adjacent to the new Nordstrom. Nordstrom at Aventura Mall is scheduled to open in Fall 2007 and will be the retailer's third location in the Greater Miami/Fort Lauderdale area, and the eighth in Florida. The company will be opening a store at the Gardens Mall in Palm Beach Gardens on March 10, 2006. (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20001011/NORDLOGO ) "We're always interested in being where our customers want us to be," said Erik Nordstrom, executive vice president of full-line stores for Nordstrom. "We opened at The Village of Merrick Park in Coral Gables in 2002 and then at Dadeland Mall just last fall, and have received a positive response from the community. Aventura Mall offers the perfect spot to expand our presence in South Florida serving local residents and out-of-town visitors who love to shop." Aventura Mall is centrally located in the heart of South Florida with more than 250 retail and specialty shops, a 24-screen movie theater and a variety of restaurants. -

Historic Overtown Culture & Entertainment District Master Plan

HISTORIC OVERTOWN CULTURE & ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT 05.30.19 / MASTER PLAN DOCUMENT 1 Historic Overtown Culture & Entertainment District TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 THE VISION 24 DESIGN FRAMEWORK - District Identity + Wayfinding - District Parking - Project Aspirations - Design Elements - Renderings - Community Input - 2nd Avenue Cultural Corridor - Historic Themes - Massing Strategies 52 PROGRAM + METRICS - Architectural Design Framework 16 SITE ANALYSIS - Public Realm Framework - Development Metrics - 9th Street - Public Infrastructure Projects - Location - 2nd Court - Phasing Strategy - Overtown’s Historic Grid - 2nd Avenue - Parcel Ownership - Adjacencies + Connectivity - Design Vision - Current - Street Hierarchy - Public Realm / Parklets - Transactions - Key Existing + Planned Assets - Public Realm / Materiality + Identity - Proposed - District Resilience 2 Historic Overtown Culture & Entertainment District THE VISION The Overtown Culture & Entertainment District will once again become a destination, and will be a place for people to live, work and enjoy its unique history and culture. In 1997 The Black Archives History and Research Foundation destination, and a place for people to live, work and enjoy the unique commissioned a master plan study for the Overtown Folklife Village history and culture that is integral to Miami. to create a unique, pedestrian scaled village environment to anchor the historic core of Overtown; this report builds on that study with an • Create a distinct place that reclaims the role of Blacks in the expanded scope and extent that reflects the changes that have taken history and culture of Miami: An authentically Black experience. place in Miami since that time. • Re-establish Overtown as Miami’s center for Black culture, For most of the 20th century Overtown was a vibrant community that entertainment, innovation and entrepreneurship. -

Miami Condos Most at Risk Sea Level Rise

MIAMI CONDOS MIAMI CONDOS MOST AT RISK www.emiami.condos SEA LEVEL RISE RED ZONE 2’ 3’ 4’ Miami Beach Miami Beach Miami Beach Venetian Isle Apartments - Venetian Isle Apartments - Venetian Isle Apartments - Island Terrace Condominium - Island Terrace Condominium - Island Terrace Condominium - Costa Brava Condominium - -Costa Brava Condominium - -Costa Brava Condominium - Alton Park Condo - Alton Park Condo - Alton Park Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Floridian Condominiums - Floridian Condominiums - Floridian Condominiums - South Beach Bayside Condominium - South Beach Bayside Condominium - South Beach Bayside Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - La Tour Condominium - La Tour Condominium - La Tour Condominium - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Tower 41 Condominium - Tower 41 Condominium - Tower 41 Condominium - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Mimosa Condominium - Mimosa Condominium - Mimosa Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Marlborough House - Marlborough House - Marlborough House - Grandview - Grandview - Grandview - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Sherry Frontenac - Sherry Frontenac - Sherry Frontenac - Carillon - Carillon - Carillon - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Harbor House - Harbor House