Making Mathematics American: Gender, Professionalization, and Abstraction During the Growth of Mathematics in the United States, 1890-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JM Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston

1 'Presences of the Infinite': J. M. Coetzee and Mathematics Peter Johnston PhD Royal Holloway University of London 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Peter Johnston, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Dated: 3 Abstract This thesis articulates the resonances between J. M. Coetzee's lifelong engagement with mathematics and his practice as a novelist, critic, and poet. Though the critical discourse surrounding Coetzee's literary work continues to flourish, and though the basic details of his background in mathematics are now widely acknowledged, his inheritance from that background has not yet been the subject of a comprehensive and mathematically- literate account. In providing such an account, I propose that these two strands of his intellectual trajectory not only developed in parallel, but together engendered several of the characteristic qualities of his finest work. The structure of the thesis is essentially thematic, but is also broadly chronological. Chapter 1 focuses on Coetzee's poetry, charting the increasing involvement of mathematical concepts and methods in his practice and poetics between 1958 and 1979. Chapter 2 situates his master's thesis alongside archival materials from the early stages of his academic career, and thus traces the development of his philosophical interest in the migration of quantificatory metaphors into other conceptual domains. Concentrating on his doctoral thesis and a series of contemporaneous reviews, essays, and lecture notes, Chapter 3 details the calculated ambivalence with which he therein articulates, adopts, and challenges various statistical methods designed to disclose objective truth. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society

ISSN 0002-9920 of the American Mathematical Society February 2006 Volume 53, Number 2 Math Circles and Olympiads MSRI Asks: Is the U.S. Coming of Age? page 200 A System of Axioms of Set Theory for the Rationalists page 206 Durham Meeting page 299 San Francisco Meeting page 302 ICM Madrid 2006 (see page 213) > To mak• an antmat•d tub• plot Animated Tube Plot 1 Type an expression in one or :;)~~~G~~~t;~~i~~~~~~~~~~~~~:rtwo ' 2 Wrth the insertion point in the 3 Open the Plot Properties dialog the same variables Tl'le next animation shows • knot Plot 30 Animated + Tube Scientific Word ... version 5.5 Scientific Word"' offers the same features as Scientific WorkPlace, without the computer algebra system. Editors INTERNATIONAL Morris Weisfeld Editor-in-Chief Enrico Arbarello MATHEMATICS Joseph Bernstein Enrico Bombieri Richard E. Borcherds Alexei Borodin RESEARCH PAPERS Jean Bourgain Marc Burger James W. Cogdell http://www.hindawi.com/journals/imrp/ Tobias Colding Corrado De Concini IMRP provides very fast publication of lengthy research articles of high current interest in Percy Deift all areas of mathematics. All articles are fully refereed and are judged by their contribution Robbert Dijkgraaf to the advancement of the state of the science of mathematics. Issues are published as S. K. Donaldson frequently as necessary. Each issue will contain only one article. IMRP is expected to publish 400± pages in 2006. Yakov Eliashberg Edward Frenkel Articles of at least 50 pages are welcome and all articles are refereed and judged for Emmanuel Hebey correctness, interest, originality, depth, and applicability. Submissions are made by e-mail to Dennis Hejhal [email protected]. -

Boyer Is the Martin A

II “WE ARE ALL ISLANDERS TO BEGIN WITH”: THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO AND THE WORLD IN THE LATE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES J OHN W. B OYER OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON HIGHER XVIIEDUCATION XVII THE COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Hermann von Holst, oil portrait by Karl Marr, 1903 I I “WE ARE ALL ISLANDERS TO BEGIN WITH”: The University of Chicago and the World in the Late Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries INTRODUCTION he academic year 2007–08 has begun much like last year: our first-year class is once again the largest in T our history, with over 1,380 new students, and as a result we have the highest Autumn Quarter enroll- ment in our history at approximately 4,900. We can be proud of the achievements and the competitiveness of our entering class, and I have no doubt that their admirable test scores, class ranks, and high school grade point averages will show their real meaning for us in the energy, intelligence, and dedication with which our new students approach their academic work and their community lives in the College. I have already received many reports from colleagues teaching first-year humanities general education sections about how bright, dedicated, and energetic our newest students are. To the extent that we can continue to recruit these kinds of superb students, the longer-term future of the College is bright indeed. We can also be very proud of our most recent graduating class. The Class of 2007 won a record number of Fulbright grants — a fact that I will return to in a few moments — but members of the class were rec- ognized in other ways as well, including seven Medical Scientist Training This essay was originally presented as the Annual Report to the Faculty of the College on October 30, 2007. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 10:06:53AM Via Free Access 268 Revue De Synthèse : TOME 139 7E SÉRIE N° 3-4 (2018) Chercheur Pour IBM

REVUE DE SYNTHÈSE : TOME 139 7e SÉRIE N° 3-4 (2018) 267-288 brill.com/rds A Task that Exceeded the Technology: Early Applications of the Computer to the Lunar Three-body Problem Allan Olley* Abstract: The lunar Three-Body problem is a famously intractable problem of Newtonian mechanics. The demand for accurate predictions of lunar motion led to practical approximate solutions of great complexity, constituted by trigonometric series with hundreds of terms. Such considerations meant there was demand for high speed machine computation from astronomers during the earliest stages of computer development. One early innovator in this regard was Wallace J. Eckert, a Columbia University professor of astronomer and IBM researcher. His work illustrates some interesting features of the interaction between computers and astronomy. Keywords: history of astronomy – three body problem – history of computers – Wallace J. Eckert Une tâche excédant la technologie : l’utilisation de l’ordinateur dans le problème lunaire des trois corps Résumé : Le problème des trois corps appliqué à la lune est un problème classique de la mécanique newtonienne, connu pour être insoluble avec des méthodes exactes. La demande pour des prévisions précises du mouvement lunaire menait à des solutions d’approximation pratiques qui étaient d’une complexité considérable, avec des séries tri- gonométriques contenant des centaines de termes. Cela a très tôt poussé les astronomes à chercher des outils de calcul et ils ont été parmi les premiers à utiliser des calculatrices rapides, dès les débuts du développement des ordinateurs modernes. Un innovateur des ces années-là est Wallace J. Eckert, professeur d’astronomie à Columbia University et * Allan Olley, born in 1979, he obtained his PhD-degree from the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science Technology (IHPST), University of Toronto in 2011. -

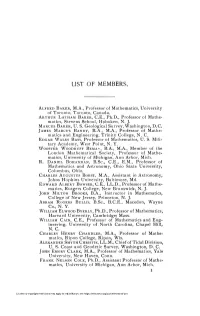

List of Members

LIST OF MEMBERS, ALFRED BAKER, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada. ARTHUR LATHAM BAKER, C.E., Ph.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Stevens School, Hpboken., N. J. MARCUS BAKER, U. S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. JAMES MARCUS BANDY, B.A., M.A., Professor of Mathe matics and Engineering, Trinit)^ College, N. C. EDGAR WALES BASS, Professor of Mathematics, U. S. Mili tary Academy, West Point, N. Y. WOOSTER WOODRUFF BEMAN, B.A., M.A., Member of the London Mathematical Society, Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. R. DANIEL BOHANNAN, B.Sc, CE., E.M., Professor of Mathematics and Astronomy, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. CHARLES AUGUSTUS BORST, M.A., Assistant in Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md. EDWARD ALBERT BOWSER, CE., LL.D., Professor of Mathe matics, Rutgers College, New Brunswick, N. J. JOHN MILTON BROOKS, B.A., Instructor in Mathematics, College of New Jersey, Princeton, N. J. ABRAM ROGERS BULLIS, B.SC, B.C.E., Macedon, Wayne Co., N. Y. WILLIAM ELWOOD BYERLY, Ph.D., Professor of Mathematics, Harvard University, Cambridge*, Mass. WILLIAM CAIN, C.E., Professor of Mathematics and Eng ineering, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N. C. CHARLES HENRY CHANDLER, M.A., Professor of Mathe matics, Ripon College, Ripon, Wis. ALEXANDER SMYTH CHRISTIE, LL.M., Chief of Tidal Division, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D. C. JOHN EMORY CLARK, M.A., Professor of Mathematics, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. FRANK NELSON COLE, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Mathe matics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich. -

Interview of Albert Tucker

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange About Harlan D. Mills Science Alliance 9-1975 Interview of Albert Tucker Terry Speed Evar Nering Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_harlanabout Part of the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Speed, Terry and Nering, Evar, "Interview of Albert Tucker" (1975). About Harlan D. Mills. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_harlanabout/13 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Science Alliance at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in About Harlan D. Mills by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Princeton Mathematics Community in the 1930s (PMC39)The Princeton Mathematics Community in the 1930s Transcript Number 39 (PMC39) © The Trustees of Princeton University, 1985 ALBERT TUCKER CAREER, PART 2 This is a continuation of the account of the career of Albert Tucker that was begun in the interview conducted by Terry Speed in September 1975. This recording was made in March 1977 by Evar Nering at his apartment in Scottsdale, Arizona. Tucker: I have recently received the tapes that Speed made and find that these tapes carried my history up to approximately 1938. So the plan is to continue the history. In the late '30s I was working in combinatorial topology with not a great deal of results to show. I guess I was really more interested in my teaching. I had an opportunity to teach an undergraduate course in topology, combinatorial topology that is, classification of 2-dimensional surfaces and that sort of thing. -

Wallace Eckert

Wallace Eckert Nakumbuka Dk Eckert aliniambia, "Siku moja, kila mtu atakuwa na kompyuta kwenye dawati lao." Macho yangu yalifunguka. Hiyo lazima iwe katika miaka mapema ya 1950’s. Aliona mapema. -Eleanor Krawitz Kolchin, mahojiano ya Huffington Post, Februari 2013. Picha: Karibu 1930, Jalada la Columbiana. Wallace John Eckert, 1902-1971. Pamoja na masomo ya kuhitimu huko Columbia, Chuo Kikuu cha Chicago, na Yale, alipokea Ph.D. kutoka Yale mnamo 1931 chini ya Profesa Ernest William Brown (1866-1938), ambaye alitumia kazi yake katika kuendeleza nadharia ya mwongozo wa mwezi. Maarufu zaidi kwa mahesabu ya mzunguko wa mwezi ambayo yaliongoza misheni ya Apollo kwenda kwa mwezi, Eckert alikuwa Profesa wa Sayansi ya Chuo Kikuu cha Columbia kutoka 1926 hadi 1970, mwanzilishi na Mkurugenzi wa Ofisi ya Taasisi ya Taaluma ya Thomas J. Watson katika Chuo Kikuu cha Columbia (1937-40), Mkurugenzi wa Ofisi ya Amerika ya US Naval Observatory Nautical Almanac (1940-45), na mwanzilishi na Mkurugenzi wa Maabara ya Sayansi ya Watson ya Sayansi katika Chuo Kikuu cha Columbia (1945-1966). Kwanza kabisa, na daima ni mtaalam wa nyota, Eckert aliendesha na mara nyingi alisimamia ujenzi wa mashine za kompyuta zenye nguvu kusuluhisha shida katika mechanics ya mbinguni, haswa ili kuhakikisha, kupanua, na kuboresha nadharia ya Brown. Alikuwa mmoja wa kwanza kutumia mashine za kadi za kuchomwa kwa suluhisho la shida tata za kisayansi. Labda kwa maana zaidi, alikuwa wa kwanza kusasisha mchakato wakati, mnamo 1933-34, aliunganisha mahesabu na kompyuta za IBM kadhaa na mzunguko wa vifaa na vifaa vya muundo wake ili kusuluhisha usawa wa aina, njia ambazo baadaye zilibadilishwa na kupanuliwa kwa IBM ya "Aberdeen "Calculator inayoweza kupatikana ya Udhibiti wa Mpangilio, Punch Kuhesabu elektroniki, Calculator ya Kadi iliyopangwa, na SSEC. -

I Iistory Ofsoence

ISSN 0739-4934 NEWSLETTER I IISTORY OFSOENCE .~.o.~.~.~.~.Js.4 ..N· u·M·B·ER.. 2............ _________ S00E~~ 1984 HSS EXECUTIVE PRESIDENTIAL COMMITTEE ADDRESS PRESIDENT EDWARD GRANT, Indiana University VICE-PRESIDENT WILLIAM COLEMAN, University of BY GERALD HOLTON Wisconsin - Madison SECRETI\RY AUDREY DAVIS, Smithsonian Institution DELIVERED AT THE ANNUAL HSS BANQUET, 1REASURER PALMER HOUSE HOTEL, Cl-ITCAGO, SPENCER R. WEART, American Institute of Physics 29 DECEMBER 1985 EDITOR ARNOLD THACKRAY, University of Pennsylvania It is surely appropriate, and should routinely be the case, that a retiring presi dent of a professional society give some accounting of his stewardship. Which The History of Science Society was founded in of the expectations raised four years earlier, when he ran for office, have been 1924 to secure the future of Isis, the international reasonably fulfilled? Which of the promises were kept, and which proved to be review that George Sarton (1884-19561 bad too difficult for the time being, despite best efforts? Where does the Society now founded in Belgium in 1912. The Society seeks to stand, viewed as an organization whose main purpose is to support the work foster interest in the history of science and its so cial and cultural relations, to provide a forum for and careers of its members? And what must still be done in this period of discussion, and to promote scholarly research in growth, by each of us pitching in on some task? the history of science. The Society pursues these To discuss these issues is to point out the opportunities for your personal and objectives by the publication of its journal Isis, by continued involvement in the affairs of our Society. -

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Individual Fates and Global Impact Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright 2009 © by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siegmund-Schultze, R. (Reinhard) Mathematicians fleeing from Nazi Germany: individual fates and global impact / Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-12593-0 (cloth) — ISBN 978-0-691-14041-4 (pbk.) 1. Mathematicians—Germany—History—20th century. 2. Mathematicians— United States—History—20th century. 3. Mathematicians—Germany—Biography. 4. Mathematicians—United States—Biography. 5. World War, 1939–1945— Refuges—Germany. 6. Germany—Emigration and immigration—History—1933–1945. 7. Germans—United States—History—20th century. 8. Immigrants—United States—History—20th century. 9. Mathematics—Germany—History—20th century. 10. Mathematics—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. QA27.G4S53 2008 510.09'04—dc22 2008048855 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 Contents List of Figures and Tables xiii Preface xvii Chapter 1 The Terms “German-Speaking Mathematician,” “Forced,” and“Voluntary Emigration” 1 Chapter 2 The Notion of “Mathematician” Plus Quantitative Figures on Persecution 13 Chapter 3 Early Emigration 30 3.1. The Push-Factor 32 3.2. The Pull-Factor 36 3.D. -

Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Department Of

Basilios Bessarion Mystras 1436 Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 Università di Padova 1444 Academic Genealogy of the Oakland University Vittorino da Feltre Marsilio Ficino Cristoforo Landino Università di Padova 1416 Università di Firenze 1462 Theodoros Gazes Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Università di Mantova 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Firenze 1477 Constantinople 1433 DepartmentThe Mathematics Genealogy Project of is a serviceMathematics of North Dakota State University and and the American Statistics Mathematical Society. Demetrios Chalcocondyles http://www.mathgenealogy.org/ Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Accademia Romana 1452 Université de Paris 1363, 1375 Université Catholique de Louvain 1485 Università di Firenze 1493 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1478 Mystras 1452 Jan Standonck Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Johannes von Gmunden Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Jean Tagault François Dubois Janus Lascaris Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes Stöffler Collège Sainte-Barbe 1474 Universität Basel 1477 Universität Wien 1406 Università di Padova Università di Padova Université Catholique de Louvain 1504, 1515 Université de Paris 1516 Università di Padova 1472 Università -

E. T. Bell and Mathematics at Caltech Between the Wars Judith R

E. T. Bell and Mathematics at Caltech between the Wars Judith R. Goodstein and Donald Babbitt E. T. (Eric Temple) Bell, num- who was in the act of transforming what had been ber theorist, science fiction a modest technical school into one of the coun- novelist (as John Taine), and try’s foremost scientific institutes. It had started a man of strong opinions out in 1891 as Throop University (later, Throop about many things, joined Polytechnic Institute), named for its founder, phi- the faculty of the California lanthropist Amos G. Throop. At the end of World Institute of Technology in War I, Throop underwent a radical transformation, the fall of 1926 as a pro- and by 1921 it had a new name, a handsome en- fessor of mathematics. At dowment, and, under Millikan, a new educational forty-three, “he [had] be- philosophy [Goo 91]. come a very hot commodity Catalog descriptions of Caltech’s program of in mathematics” [Rei 01], advanced study and research in pure mathematics having spent fourteen years in the 1920s were intended to interest “students on the faculty of the Univer- specializing in mathematics…to devote some sity of Washington, along of their attention to the modern applications of with prestigious teaching mathematics” and promised “to provide defi- stints at Harvard and the nitely for such a liaison between pure and applied All photos courtesy of the Archives, California Institute of Technology. of Institute California Archives, the of courtesy photos All University of Chicago. Two Eric Temple Bell (1883–1960), ca. mathematics by the addition of instructors whose years before his arrival in 1951. -

Mcshane-E-J.Pdf

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES EDWARD JAMES MCSHANE 1904–1989 A Biographical Memoir by LEONARD D. BERKOVITZ AND WENDELL H. FLEMING Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs, VOLUME 80 PUBLISHED 2001 BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. EDWARD JAMES MCSHANE May 10, 1904–June 1, 1989 BY LEONARD D. BERKOVITZ AND WENDELL H. FLEMING URING HIS LONG CAREER Edward James McShane made D significant contributions to the calculus of variations, integration theory, stochastic calculus, and exterior ballistics. In addition, he served as a national leader in mathematical and science policy matters and in efforts to improve the undergraduate mathematical curriculum. McShane was born in New Orleans on May 10, 1904, and grew up there. His father, Augustus, was a medical doctor and his mother, Harriet, a former schoolteacher. He gradu- ated from Tulane University in 1925, receiving simultaneously bachelor of engineering and bachelor of science degrees, as well as election to Phi Beta Kappa. He turned down an offer from General Electric and instead continued as a student instructor of mathematics at Tulane, receiving a master’s degree in 1927. In the summer of 1927 McShane entered graduate school at the University of Chicago, from which he received his Ph.D. in 1930 under the supervision of Gilbert Ames Bliss. He interrupted his studies during 1928-29 for financial reasons to teach at the University of Wichita. It was at Chicago that McShane’s long-standing interest in the calculus of variations began.