NOTES on the EAST AFRICAN MIOCENE PRIMATES. by D. G. Macinnes,Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unravelling the Positional Behaviour of Fossil Hominoids: Morphofunctional and Structural Analysis of the Primate Hindlimb

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Doctorado en Biodiversitat Facultad de Ciènces Tesis doctoral Unravelling the positional behaviour of fossil hominoids: Morphofunctional and structural analysis of the primate hindlimb Marta Pina Miguel 2016 Memoria presentada por Marta Pina Miguel para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, programa de doctorado en Biodiversitat del Departamento de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia (Facultad de Ciències). Este trabajo ha sido dirigido por el Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont) y el Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez (The George Washington Univertisy). Director Co-director Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez A mis padres y hermana. Y a todas aquelas personas que un día decidieron perseguir un sueño Contents Acknowledgments [in Spanish] 13 Abstract 19 Resumen 21 Section I. Introduction 23 Hominoid positional behaviour The great apes of the Vallès-Penedès Basin: State-of-the-art Section II. Objectives 55 Section III. Material and Methods 59 Hindlimb fossil remains of the Vallès-Penedès hominoids Comparative sample Area of study: The Vallès-Penedès Basin Methodology: Generalities and principles Section IV. -

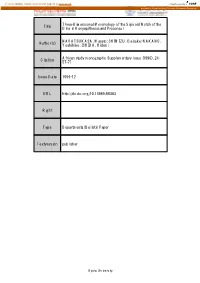

Title Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of the Title Ulna in Kenyapithecus and Proconsul NAKATSUKASA, Masato; SHIMIZU, Daisuke; NAKANO, Author(s) Yoshihiko; ISHIDA, Hidemi African study monographs. Supplementary issue (1996), 24: Citation 57-71 Issue Date 1996-12 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68383 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 24: 57-71, December 1996 57 THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF THE SIGMOID NOTCH OF THE ULNA IN KENYAPITHECUS AND PROCONSUL Masato Nakatsukasa Daisuke Shimizu Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University Yoshihiko Nakano Department of Biological Anthropology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Osaka University Hidemi Ishida Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University ABSTRACT The three-dimensional (3-D) morphology of the sigmoid notch was examined in Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, and several living anthropoids by using an automatic 3-D digitizer. It was revealed that Kenyapithecus and Proconsul exhibit a very similar morphology of the dis tal region of the sigmoid notch; including the absence of a median keel and a downward sloped coronoid process. In addition, the proxilnal region of the sigmoid notch is curved more acutely relative to the distal region in Proconsul. This morphological complex is unique and not found in the examined living primates. The benefits of 3-D morphometries are discussed. Key Words: Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, sigmoid notch, three-dimensional morphometrics, ulna. INTRODUCTION Recently, automatic three-dimensional (3-0) digitizers have become more fre quently to be used for biometrics. -

Glaciation (Oakley, 1950). Variations in the Proposed Beginning Dates

EVOLUTION OF THE HUMAN HAND AMD THE GREAT HAND-AXE TRADITION Grover S. Krantz The hand-axe is both the earliest and the longest persisting of standar- dized stone tools. They present a continuous history of one tool type from the first to the third interglacial periods, a span.of at least 200,000 years and perhaps as many as half a million. Equally remarkable is their geographical range which covers all of Africa, western Europe and southern Asia--fully half of-the then habitable Old Vorld. Aside from differences in the local stone that was utilized, hand-axes from this whole area are constructed on the same plan and show no clear regional typology. Other tool types occur with hand-axes: utilized flakes are found at all levels, and in the later half of the sequence there-are cleavers, ovates, trimmed flakes and spherical stone balls. Throughout the sequence, however, the basic design of the hand-axe continues with its intended formnapparently unchanged. We thus have a continuous record of man's attempts to produce a single type of 'implement over mst of his tool making history. (See Figure 1.) Recent discoveries of fossil man have made it increasingly evident that biological evolution of the human body was also in progress coincident with the development of ancient stone tool types. 'While the exact time of appearance of Homo siens is still in some dispute (see Stewart, 1950 and Oakley., 1957), it is no nowseriously maintained that the earliest tool makers necessarily approximated the modern or even the neanderthal morphologies. -

8. Primate Evolution

8. Primate Evolution Jonathan M. G. Perry, Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Stephanie L. Canington, B.A., The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Learning Objectives • Understand the major trends in primate evolution from the origin of primates to the origin of our own species • Learn about primate adaptations and how they characterize major primate groups • Discuss the kinds of evidence that anthropologists use to find out how extinct primates are related to each other and to living primates • Recognize how the changing geography and climate of Earth have influenced where and when primates have thrived or gone extinct The first fifty million years of primate evolution was a series of adaptive radiations leading to the diversification of the earliest lemurs, monkeys, and apes. The primate story begins in the canopy and understory of conifer-dominated forests, with our small, furtive ancestors subsisting at night, beneath the notice of day-active dinosaurs. From the archaic plesiadapiforms (archaic primates) to the earliest groups of true primates (euprimates), the origin of our own order is characterized by the struggle for new food sources and microhabitats in the arboreal setting. Climate change forced major extinctions as the northern continents became increasingly dry, cold, and seasonal and as tropical rainforests gave way to deciduous forests, woodlands, and eventually grasslands. Lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers—once diverse groups containing many species—became rare, except for lemurs in Madagascar where there were no anthropoid competitors and perhaps few predators. Meanwhile, anthropoids (monkeys and apes) emerged in the Old World, then dispersed across parts of the northern hemisphere, Africa, and ultimately South America. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Wrist and Ankle Morphology of Hominoids and Lorisids, with Implications for the Evolution of Hominoid Locomotion

Durham E-Theses A comparative analysis of the wrist and ankle morphology of hominoids and lorisids, with implications for the evolution of hominoid locomotion Read, Catriona S. How to cite: Read, Catriona S. (2001) A comparative analysis of the wrist and ankle morphology of hominoids and lorisids, with implications for the evolution of hominoid locomotion, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3775/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 A Comparative Analysis of the Wrist and Ankle Morphology of Hominoids and Lorisids, with Implications for the Evolution of Hominoid Locomotion A Dissertation presented by Catriona S. Read to The Graduate School For the degree of Master of Science m Biological Anthropology Department of Anthropology University of Durham September 2001 The co11yright of this thesis rests with the author. -

Ancestral Facial Morphology of Old World Higher Primates (Anthropoidea/Catarrhini/Miocene/Cranium/Anatomy) BRENDA R

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 88, pp. 5267-5271, June 1991 Evolution Ancestral facial morphology of Old World higher primates (Anthropoidea/Catarrhini/Miocene/cranium/anatomy) BRENDA R. BENEFIT* AND MONTE L. MCCROSSINt *Department of Anthropology, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901; and tDepartment of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 Communicated by F. Clark Howell, March 11, 1991 ABSTRACT Fossil remains of the cercopithecoid Victoia- (1, 5, 6). Contrasting craniofacial configurations of cercopithe- pithecus recently recovered from middle Miocene deposits of cines and great apes are, in consequence, held to be indepen- Maboko Island (Kenya) provide evidence ofthe cranial anatomy dently derived with regard to the ancestral catarrhine condition of Old World monkeys prior to the evolutionary divergence of (1, 5, 6). This reconstruction has formed the basis of influential the extant subfamilies Colobinae and Cercopithecinae. Victoria- cladistic assessments ofthe phylogenetic relationships between pithecus shares a suite ofcraniofacial features with the Oligocene extant and extinct catarrhines (1, 2). catarrhine Aegyptopithecus and early Miocene hominoid Afro- Reconstructions of the ancestral catarrhine morphotype pithecus. AU three genera manifest supraorbital costae, anteri- are based on commonalities of subordinate morphotypes for orly convergent temporal lines, the absence of a postglabellar Cercopithecoidea and Hominoidea (1, 5, 6). Broadly distrib- fossa, a moderate to long snout, great facial -

08 Early Primate Evolution

Paper No. : 14 Human Origin and Evolution Module : 08 Early Primate Evolution Development Team Principal Investigator Prof. Anup Kumar Kapoor Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Dr. Satwanti Kapoor (Retd Professor) Paper Coordinator Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Mr. Vijit Deepani & Prof. A.K. Kapoor Content Writer Department of Anthropology, University of Delhi Prof. R.K. Pathak Content Reviewer Department of Anthropology, Panjab University, Chandigarh 1 Early Primate Evolution Anthropology Description of Module Subject Name Anthropology Paper Name Human Origin and Evolution Module Name/Title Early Primate Evolution Module Id 08 Contents: Fossil Primates: Introduction Theories of primate origin Primates: Pre- Pleistocene Period a. Palaeocene epoch b. Eocene epoch c. Oligocene epoch d. Miocene – Pliocene epoch Summary Learning outcomes: The learner will be able to develop: an understanding about fossil primates and theories of primate origin. an insight about the extinct primate types of Pre-Pleistocene Period. 2 Early Primate Evolution Anthropology Fossil Primates: Introduction In modern time, the living primates are graded in four principle domains – Prosimian, Monkey, Ape and man. On the basis of examination of fossil evidences, it has been established that all the living primates have evolved and ‘adaptively radiated’ from a common ancestor. Fossil primates exhibit a palaeontological record of evolutionary processes that occurred over the last 65 to 80 million years. Crucial evidence of intermediate forms, that bridge the gap between extinct and extant taxa, is yielded by the macroevolutionary study of the primate fossil evidences. The paleoanthropologists often utilize the comparative anatomical method to develop insight about morphological adaptations in fossil primates. -

Proconsul Africanus: an Examination of Its Anatomy and Evidence for Its

Perspectives Proconsul africanus: lutionists claim P. africanus lived from 19–17 Ma an examination of (though some sources extend the range to 23–14 its anatomy and Ma) with the KNM-RU evidence for its 7290 specimen falling in the middle at 18 million extinction in a post- years old. Flood catastrophe With the scarcity of hominid fossils from sites alleged to be 3 million Matthew Murdock years old, it is unlikely that so many of the delicate In 1948, Dr Mary Leakey found a Proconsul bones, such as distorted skull at Site R106 on Rusinga vertebrae, wrist and ankle Island, Western Kenya. The find was bones, and ‘thousands of a nearly complete cranium, mandi finger bones’ of baby pro ble and full dentition. Because the Figure 1. Left side of P. africanus cranium KNM-RU 7290 consuls, found during later showing crushed and distorted parietal. skull did not resemble any previously excavations would survive found, a new genus was named for six times longer. These KNMRU 7290 is remarkable this individual. Arthur Hopwood of bones are most likely postFlood, and in that it preserves all 32 teeth. The 11 the Natural History Museum (London) only a few thousand years old. dental formula is 2:1:2:3 in both the coined the name ‘Proconsul’ in honour upper and lower jaw. Proconsul has of the circus chimp ‘Consul the Great’, The skull the typical 5-Y pattern of cusps which which had become famous for riding is seen in the lower molars of other a bicycle, and smoking cigarettes.1,2 The distorted cranium possesses hominoids (Figure 2). -

The Joints of the Evolving Foot. Part M. the Fossil Evidence

J. Anat. (1980), 131, 2, pp. 275-298 275 With 8 figures Printed in Great Britain The joints of the evolving foot. Part m. The fossil evidence 0. J. LEWIS Department of Anatomy, St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical College, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ (Accepted 8 January 1980) INTRODUCTION In the previous two papers (Lewis, 1980a, b) an analysis of form and function in the joints of the primate foot revealed that the human foot presents certain unique features. Yet affinity with other Primates, and particularly the great apes, is abundantly manifest and the unique human attributes are progressive modifications of functional complexes which were initially evolved for arboreal life; in this sense the arboreal foot was pre-adaptive to the specialized structure required by terrestrial bipedal man. In the present paper an attempt will be made to formulate an hypothesis which can explain the morphological changes which could have remodelled an ape-like foot in such a way as to adapt it to essentially human functions. Ideally, this hypothesis should highlight the key features of changed morphology. Modern methods of constructing phylogenies (Delson, 1977; Tattersall & Eldredge, 1977) largely focus attention on such derived, specialized or apomorphic characters. Using these apomorphic features some of the fossil evidence will be examined with a view to establishing a phylogenetic tree and eventually a reasonable scenario for the evolution of man. Fortuitously, fossil tali and calcanei which carry the imprints of many of the apomorphic characters are relatively abundant. Even more valuable is the almost complete tarsus and metatarsus from Bed I, Olduvai Gorge (Olduvai Hominid 8) dated at 1-7 million years before the present. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Moya` -Sola` et al. 10.1073/pnas.0811730106 SI Text netic relationships between all these taxa by classifying them all Systematic Framework. In Table S1 we provide a systematic into a single family Afropithecidae with 2 subfamilies (Keny- classification of living and fossil Hominoidea to the tribe level, apithecinae and Afropithecinae). by further including extant taxa and extinct genera discussed in The systematic scheme used here requires several nomencla- this paper. Hominoidea are defined as the group constituted by tural decisions, which deserve further explanation. The nomina Hylobatidae and Hominidae, plus all extinct taxa more closely Kenyapithecini and Kenyapithecinae are adopted instead of related to them than to Cercopithecoidea. Hominidae, in turn, Griphopithecinae and Griphopithecini (see also ref. 25) merely are defined as the group containing Ponginae and Homininae, because the former have priority. It is unclear why neither Begun plus all extinct forms more closely related to them than to (1) nor Kelley (2) specify the authorship of Griphopithecinae (or Hylobatidae. While this broad concept of Hominidae is currently Griphopithecidae), but, to our knowledge, the authorship of the used by many paleoprimatologists (e.g., refs. 1–2), the systematic latter nomina must be attributed to Begun (ref. 4, p. 232: Table position of primitive (or archaic) putative hominoids is far from 10.1), which therefore do not have priority over Kenyapithecinae clear (see below). Begun (3–5) employs the terms ‘‘Eohomi- Andrews, 1992. Griphopithecinae thus remains potentially valid noidea’’ and ‘‘Euhominoidea’’ to informally refer to hominoids only if Kenyapithecus (and Afropithecus, see below) are excluded of primitive and modern aspect, respectively. -

The Evolution of Human and Ape Hand Proportions

ARTICLE Received 6 Feb 2015 | Accepted 4 Jun 2015 | Published 14 Jul 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8717 OPEN The evolution of human and ape hand proportions Sergio Alme´cija1,2,3, Jeroen B. Smaers4 & William L. Jungers2 Human hands are distinguished from apes by possessing longer thumbs relative to fingers. However, this simple ape-human dichotomy fails to provide an adequate framework for testing competing hypotheses of human evolution and for reconstructing the morphology of the last common ancestor (LCA) of humans and chimpanzees. We inspect human and ape hand-length proportions using phylogenetically informed morphometric analyses and test alternative models of evolution along the anthropoid tree of life, including fossils like the plesiomorphic ape Proconsul heseloni and the hominins Ardipithecus ramidus and Australopithecus sediba. Our results reveal high levels of hand disparity among modern hominoids, which are explained by different evolutionary processes: autapomorphic evolution in hylobatids (extreme digital and thumb elongation), convergent adaptation between chimpanzees and orangutans (digital elongation) and comparatively little change in gorillas and hominins. The human (and australopith) high thumb-to-digits ratio required little change since the LCA, and was acquired convergently with other highly dexterous anthropoids. 1 Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052, USA. 2 Department of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York 11794, USA. 3 Institut Catala` de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP), Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici Z (ICTA-ICP), campus de la UAB, c/ de les Columnes, s/n., 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s (Barcelona), Spain. -

Hominid Adaptations and Extinctions Reviewed by MONTE L. Mccrossin

Hominid Adaptations and Extinctions David W. Cameron Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2004, 260 pp. (hardback), $60.00. ISBN 0-86840-716-X Reviewed by MONTE L. McCROSSIN Department of Sociology and Anthropology, New Mexico State University, P.O. Box 30001, Las Cruces, NM 88003, USA; [email protected] According to David W. Cameron, the goal of his book Asian and African great apes), and the subfamily Gorillinae Hominid Adaptations and Extinctions is “to examine the (Graecopithecus). Cameron states that “the aim of this book, evolution of ape morphological form in association with however, is to re-examine and if necessary revise this ten- adaptive strategies and to understand what were the envi- tative evolutionary scheme” (p. 10). With regard to his in- ronmental problems facing Miocene ape groups and how clusion of the Proconsulidae in the Hominoidea, Cameron these problems influenced ape adaptive strategies” (p. 4). cites as evidence “the presence of a frontal sinus” and that Cameron describes himself as being “acknowledged inter- “they have an increased potential for raising arms above nationally as an expert on hominid evolution” and dedi- the head” (p. 10). Sadly, Cameron seems unaware of the cates the book to his “teachers, colleagues and friends” fact that the frontal sinus has been demonstrated to be a Peter Andrews and Colin Groves. He has participated in primitive feature for Old World higher primates (Rossie et fieldwork at the late Miocene sites of Rudabanya (Hunga- al. 2002). Also, no clear evidence exists for the enhanced ry) and Pasalar (Turkey). His Ph.D. at Australian National arm-raising abilities of proconsulids compared to their University was devoted to “European Miocene faciodental contemporaries, including the victoriapithecids.