Pyne's Ground-Plum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legumes of the North-Central States: C

LEGUMES OF THE NORTH-CENTRAL STATES: C-ALEGEAE by Stanley Larson Welsh A Dissertation Submitted, to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Systematic Botany Approved: Signature was redacted for privacy. Signature was redacted for privacy. artment Signature was redacted for privacy. Dean of Graduat College Iowa State University Of Science and Technology Ames, Iowa I960 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORICAL ACCOUNT 3 MATERIALS AND METHODS 8 TAXONOMIC AND NOMENCLATURE TREATMENT 13 REFERENCES 158 APPENDIX A 176 APPENDIX B 202 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express his deep gratitude to Professor Duane Isely for assistance in the selection of the problem and for the con structive criticisms and words of encouragement offered throughout the course of this investigation. Support through the Iowa Agricultural Experiment Station and through the Industrial Science Research Institute made possible the field work required in this problem. Thanks are due to the curators of the many herbaria consulted during this investigation. Special thanks are due the curators of the Missouri Botanical Garden, U. S. National Museum, University of Minnesota, North Dakota Agricultural College, University of South Dakota, University of Nebraska, and University of Michigan. The cooperation of the librarians at Iowa State University is deeply appreciated. Special thanks are due Dr. G. B. Van Schaack of the Missouri Botanical Garden library. His enthusiastic assistance in finding rare botanical volumes has proved invaluable in the preparation of this paper. To the writer's wife, Stella, deepest appreciation is expressed. Her untiring devotion, work, and cooperation have made this work possible. -

Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Stones River National Battlefield

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Stones River National Battlefield Natural Resource Report NPS/STRI/NRR—2016/1141 ON THIS PAGE Native warm season grass, located south of Stones River National Battlefield visitor center Photograph by: Jeremy Aber, MTSU Geospatial Research Center ON THE COVER Karst topography in the cedar forest at the “Slaughter Pen,” Stones River National Battlefield Photograph by: Jeremy Aber, MTSU Geospatial Research Center Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Stones River National Battlefield Natural Resource Report NPS/STRI/NRR—2016/1141 Henrique Momm Zada Law Siti Nur Hidayati Jeffrey Walck Kim Sadler Mark Abolins Lydia Simpson Jeremy Aber Geospatial Research Center Department of Geosciences Middle Tennessee State University Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 February 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. -

How Illinois Kicked the Exotic Habit

HOW ILLINOIS KICKED THE EXOTIC HABIT Francis M. Harty Illinois Department of Conservation 2005 Round Bam Road Champagne, IL 61821 Introduction For the purpose of this paper, an exotic species is defined as "a plant or animal not native to North America." The history of folly surrounding the premeditated and accidental introduction of exotic animals has been well-documented (DeVos et al. 1956, Elton 1958, Hall 1963, Laycock 1966, Ehrenfeld 1970, Bratton 1974/1975, Howe and Bratton 1976, Moyle 1976, Courtenay 1978, Coblentz 1978, Iverson 1978, Weller 1981, Bratton 1982, Vale 1982, and Savidge 1987). In 1963, Dr. E. Raymond Hall wrote, "Introducing exotic species of vertebrates is unscientific, economically wasteful, politically shortsighted, and biologically wrong." Naturalizing exotic species are living time bombs, but no one knows for sure how much time we have. For example, the ring necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), touted as the Midwestern example of a good exotic introduction, has recently developed a nefarious relationship with the greater prairie chicken (Tympanuchus cupido) in Illinois. Parasitism of prairie chicken nests by hen pheasants and harassment of displaying male chickens by cock pheasants are contributing to the decline of prairie chickens in Illinois (Vance and Westemeier 1979). The interspecific competition between the exotic pheasant (which is expanding its range in Illinois) and the native prairie chicken (which is an endangered species in Illinois) may be the final factor causing the extirpation of the prairie chicken from Illinois; it has already been extirpated from neighboring Indiana. In 1953, Klimstra and Hankla wrote, "In connection with the development of a pheasant adapted to southern conditions, the compatibility of pheasants and quail (Colinus virginianus) needs to be evaluated. -

This Week's Sale Plants

THIS WEEK’S SALE PLANTS (conifers, trees, shrubs, perennials, tropical, tenders, tomatoes, pepper) Botanical Name Common Name CONIFERS Cephalotaxus harringtonia 'Duke Gardens' Japanese Plum Yew Cephalotaxus harringtonia 'Prostrata' Japanese Plum Yew Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Nana Gracilis' Dwarf Hinoki Cypress Cupressus arizonica 'Carolina Sapphire' Arizona Cypress Juniperus conferta 'Blue Pacific' Shore Juniper Juniperus horizontalis 'Wiltonii' Blue Rug Juniper Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar Taxodium distichum 'Emerald Shadow' Bald Cypress Thuja 'Green Giant' Giant Arborvitae TREES Aesculus ×neglecta 'Erythroblastos' Hybrid Buckeye Aesculus hippocastanum 'Digitata' Horsechestnut Asimina triloba 'Levfiv' Susquehanna™ Pawpaw Asimina triloba 'Wansevwan' Shenandoah™ Pawpaw Asimina triloba Pawpaw Carpinus caroliniana 'J.N. Upright' Firespire™ Musclewood Cercidiphyllum japonicum 'Rotfuchs' Red Fox Katsura Tree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Katsura Tree Davidia involucrata 'Sonoma' Dove Tree Fagus grandifolia American Beech Ginkgo biloba 'Saratoga' Ginkgo Ostrya virginiana Hop Hornbeam Quercus alba White Oak Quercus coccinea Scarlet Oak Quercus phellos Willow Oak SHRUBS Abelia ×grandiflora 'Margarita' Glossy Abelia Abelia ×grandiflora 'Rose Creek' Glossy Abelia Aesculus parviflora var. serotina 'Rogers' Bottlebrush Buckeye Aronia arbutifolia 'Brilliantissima' Chokeberry Aronia melanocarpa 'UCONNAM165' Low Scape® Mound Chokeberry Aucuba japonica 'Golden King' Japanese Aucuba Aucuba japonica 'Marmorata' Japanese Aucuba Berberis ×gladwynensis 'William -

These De Doctorat De L'universite Paris-Saclay

NNT : 2016SACLS250 THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE PARIS-SACLAY, préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud ÉCOLE DOCTORALE N° 567 Sciences du Végétal : du Gène à l’Ecosystème Spécialité de doctorat (Biologie) Par Mlle Nour Abdel Samad Titre de la thèse (CARACTERISATION GENETIQUE DU GENRE IRIS EVOLUANT DANS LA MEDITERRANEE ORIENTALE) Thèse présentée et soutenue à « Beyrouth », le « 21/09/2016 » : Composition du Jury : M., Tohmé, Georges CNRS (Liban) Président Mme, Garnatje, Teresa Institut Botànic de Barcelona (Espagne) Rapporteur M., Bacchetta, Gianluigi Università degli Studi di Cagliari (Italie) Rapporteur Mme, Nadot, Sophie Université Paris-Sud (France) Examinateur Mlle, El Chamy, Laure Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Examinateur Mme, Siljak-Yakovlev, Sonja Université Paris-Sud (France) Directeur de thèse Mme, Bou Dagher-Kharrat, Magda Université Saint-Joseph (Liban) Co-directeur de thèse UNIVERSITE SAINT-JOSEPH FACULTE DES SCIENCES THESE DE DOCTORAT DISCIPLINE : Sciences de la vie SPÉCIALITÉ : Biologie de la conservation Sujet de la thèse : Caractérisation génétique du genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Présentée par : Nour ABDEL SAMAD Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR ÈS SCIENCES Soutenue le 21/09/2016 Devant le jury composé de : Dr. Georges TOHME Président Dr. Teresa GARNATJE Rapporteur Dr. Gianluigi BACCHETTA Rapporteur Dr. Sophie NADOT Examinateur Dr. Laure EL CHAMY Examinateur Dr. Sonja SILJAK-YAKOVLEV Directeur de thèse Dr. Magda BOU DAGHER KHARRAT Directeur de thèse Titre : Caractérisation Génétique du Genre Iris évoluant dans la Méditerranée Orientale. Mots clés : Iris, Oncocyclus, région Est-Méditerranéenne, relations phylogénétiques, status taxonomique. Résumé : Le genre Iris appartient à la famille des L’approche scientifique est basée sur de nombreux Iridacées, il comprend plus de 280 espèces distribuées outils moléculaires et génétiques tels que : l’analyse de à travers l’hémisphère Nord. -

Reproductive Success and Soil Seed Bank Characteristics of <Em>Astragalus Ampullarioides</Em> and <Em>A. Holmg

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2011-07-06 Reproductive Success and Soil Seed Bank Characteristics of Astragalus ampullarioides and A. holmgreniorum (Fabaceae): Two Rare Endemics of Southwestern Utah Allyson B. Searle Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Searle, Allyson B., "Reproductive Success and Soil Seed Bank Characteristics of Astragalus ampullarioides and A. holmgreniorum (Fabaceae): Two Rare Endemics of Southwestern Utah" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 3044. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3044 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Reproductive Success and Soil Seed Bank Characteristics of Astragalus ampullarioides and A. holmgreniorum (Fabaceae), Two Rare Endemics of Southwestern Utah Allyson Searle A Thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Loreen Allphin, Chair Bruce Roundy Susan Meyer Renee Van Buren Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences Brigham Young University August 2011 Copyright © 2011 Allyson Searle All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Reproductive Success and Soil Seed Bank Characteristics of Astragalus ampullarioides and A. holmgreniorum (Fabaceae), Two Rare Endemics of Southwestern Utah Allyson Searle Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, BYU Master of Science Astragalus ampullarioides and A. holmgreniorum are two rare endemics of southwestern Utah. Over two consecutive field seasons (2009-2010) we examined pre- emergent reproductive success, based on F/F and S/O ratios, from populations of both Astragalus ampullarioides and A. -

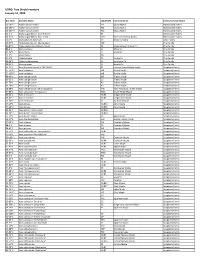

UDBG: Tree Shrub Inventory January 10, 2020

UDBG: Tree Shrub Inventory January 10, 2020 Acc. Num Scientific Name LOCATION Common Name Family Common Name 15-167*1 Abelia 'Canyon Creek' TE2 Glossy Abelia Honeysuckle Family 15-167*2 Abelia 'Canyon Creek' TE2 Glossy Abelia Honeysuckle Family 15-167*3 Abelia 'Canyon Creek' TE2 Glossy Abelia Honeysuckle Family 02-2*1 Abelia x grandiflora 'Little Richard' F5 Honeysuckle Family 18-87*1 Abelia x grandiflora 'Rose Creek' TREE Rose Creek Glossy Abelia Honeysuckle Family 70-1*1 Abeliophyllum distichum C3 White Forsythia Olive Family 15-57*1 Abies balsamea var. phanerolepis NBF Pine Family 90-47*1 Abies cephalonica 'Meyer's Dwarf' C2 Meyer's Dwarf Grecian Fir Pine Family 89-4*1 Abies concolor C1 White Fir Pine Family 01-74*1 Abies firma C1 Momi Fir Pine Family 12-9*7 Abies fraseri PILL Pine Family 71-1*2 Abies koreana C1 Korean Fir Pine Family 95-26*1 Abies nordmanniana C1 Nordmann Fir Pine Family 96-21*1 Abies pinsapo C1 Spanish Fir Pine Family 14-72*1 Acer [Crimson Sunset] = 'JFS-KW202' FE Crimson Sunset hybrid maple Soapberry Family 17-100*1 Acer barbatum WR Florida Maple Soapberry Family 17-100*2 Acer barbatum WR Florida Maple Soapberry Family 88-40*1 Acer buergerianum W2 Trident Maple Soapberry Family 91-32*1 Acer buergerianum C3 Trident Maple Soapberry Family 92-78*1 Acer buergerianum A2 Trident Maple Soapberry Family 92-78*2 Acer buergerianum A2 Trident Maple Soapberry Family 18-28*1 Acer buergerianum 'Mino Yatsubusa' FH5 Mino Yatsubusa Trident Maple Soapberry Family 94-95*1 Acer campsetre 'Compactum' WV1 Dwarf Hedge Maple Soapberry Family -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al. -

The Genus Astragalus (Fabacaeae) in Illinois

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science received 7/14/03 (2003), Volume 97, #1, pp. 11-18 accepted 11/9/03 The Genus Astragalus (Fabacaeae) in Illinois William E. McClain, Adjunct Research Associate in Botany Illinois State Museum, Springfield, Illinois 62706 and John E. Ebinger, Professor Emeritus of Botany Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois 61920 ABSTRACT Herbarium and field searches were made to determine the former and current distribution of the five Astragalus species (milk vetch) known from Illinois. Of these, the adventive A. agrestis Doug. has been reported once from the state. The native species A. crassicar- pus Nutt., A. distortus Torrey & Gray, A. tennesseensis Gray, and A. canadensis L. have experienced population declines due to habitat destruction. Astragalus canadensis is a widely distributed species of high quality prairie remnants, A. crassicarpus is known primarily from glacial drift prairies in Macoupin County, A. tennesseensis is known from a single site in Tazewell County, while only six small colonies of A. distortus survive, all from wind blown sand and loess deposits in Cass, Mason and Scott counties. Astragalus crassicarpus and A. tennesseensis are presently listed as endangered in Illinois, and endangered status is recommended for A. distortus. INTRODUCTION The genus Astragalus L., (milk vetch) is represented by more than 2,000 species in the Northern Hemisphere including 375 that occur in the United States (Isely 1998). Many are prairie and plains species of the western United States and Canada, but some occur in woodlands, barrens, and glades in the eastern United States (Gleason and Cronquist 1991). As members of the Fabaceae (Legume or Pulse Family), the genus belongs to the tribe Galegeae. -

Dry-Storage and Light Exposure Reduce Dormancy of Arabian Desert Legumes More Than Temperature

Bhatt, Bhat, Phartyal and Gallacher (2020). Seed Science and Technology, 48, 2, 247-255. https://doi.org/10.15258/sst.2020.48.2.12 Research Note Dry-storage and light exposure reduce dormancy of Arabian desert legumes more than temperature Arvind Bhatt1,2, N.R. Bhat1, Shyam S. Phartyal3* and David J. Gallacher4 1 Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research, P.O. Box 24885 Safat, 13109, Kuwait 2 Lushan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lushan, Jiujiang City, China 3 Nalanda University, School of Ecology and Environment Studies, Rajgir, 803116, India 4 School of Life and Environmental Sciences, The University of Sydney, Narrabri NSW 2390, Australia * Author for correspondence (E-mail: [email protected]) (Submitted January 2020; Accepted May 2020; Published online May 2020) Abstract Propagation and conservation of desert plants are assisted by improved understanding of seed germination ecology. The effects of dry-storage on dormancy and germination were studied in seven desert legumes. Mature seeds were collected in summer 2017 and germinated within one week of collection (fresh) and after six months (dry-storage) under two temperature and two light regimes. Seed weight of two species increased 22-55% within 24 hours of water imbibition but others increased ≤ 7%. Germination ranged from 0-32% in fresh and 2-92% in dry-stored seeds, indicating a mix of non- and physically-dormant seeds at maturity. Dry-storage at ambient room temperature was effective at relieving dormancy, though the extent was species-dependent. Germination percentage increased in response to light exposure during incubation, while the effect of temperature was species-dependent. -

Astragalus Missouriensis Nutt. Var. Humistratus Isely (Missouri Milkvetch): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Astragalus missouriensis Nutt. var. humistratus Isely (Missouri milkvetch): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project July 13, 2006 Karin Decker Colorado Natural Heritage Program Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Decker, K. (2006, July 13). Astragalus missouriensis Nutt. var. humistratus Isely (Missouri milkvetch): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/astragalusmissouriensisvarhumistratus.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work benefited greatly from the input of Colorado Natural Heritage Program botanists Dave Anderson and Peggy Lyon. Thanks also to Jill Handwerk for assistance in the preparation of this document. Nan Lederer at University of Colorado Museum Herbarium provided helpful information on Astragalus missouriensis var. humistratus specimens. AUTHOR’S BIOGRAPHY Karin Decker is an ecologist with the Colorado Natural Heritage Program (CNHP). She works with CNHP’s Ecology and Botany teams, providing ecological, statistical, GIS, and computing expertise for a variety of projects. She has worked with CNHP since 2000. Prior to this, she was an ecologist with the Colorado Natural Areas Program in Denver for four years. She is a Colorado native who has been working in the field of ecology since 1990. Before returning to school to become an ecologist she graduated from the University of Northern Colorado with a B.A. in Music (1982). She received an M.S. in Ecology from the University of Nebraska (1997), where her thesis research investigated sex ratios and sex allocation in a dioecious annual plant. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

List of Extirpated, Endangered, Threatened and Rare Vascular Plants in Indiana: An Update James R. Aldrich, John A. Bacone and Michael A. Homoya Indiana Department of Natural Resources Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 Introduction The status of Indiana's rarest vascular plants was last revised in 1981 by Bacone et al. (3). Since that publication much additional field work has been undertaken and accordingly, our knowledge of Indiana's rarest plant species has greatly increased. The results of some of this extensive field work have been discussed by Homoya (9) and Homoya and Abrell (10) for southern Indiana and by Aldrich et al. (1) for northern Indiana. Wilhelm's (17) discussion on the special vegetation of the Indiana Dunes Na- tional Lakeshore has also provided us with a much clearer understanding of the status of rare, threatened and endangered plants in northwest Indiana. Unfortunately, the number of species thought to be extinct in Indiana has more than tripled. Previous reports (2, 3) indicated that 26 species were extirpated in In- diana. The work that has been conducted to date leads us to believe that as many as 90 species may be extirpated. Without a doubt, the single factor most responsible for this extirpation has been and continues to be, the destruction of natural habitat. Compilation and Selection Criteria Lists of Bacone and Hedge (2), Bacone et al. (3), Barnes (4), Crankshaw (5) and Crovello (6) were consulted and provide the foundation for this report. New additions to this list include state records discovered since Deam (7) and a number of recommen- dations from field botanists.