Inside Llewyn Davis Blog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Folk Music As Tactical Media

‘Svec in this powerfully revisionist book shows how the HENRY ADAM SVEC folk revival’s communications milieus, metaphors, and, in a brilliant reading of Bob Dylan, its songs, had already discovered that “the folk and the machine are often one and the same”. From Lomax‘s computer-generated Global American Jukebox and Dylan’s Telecaster to today’s music apps and YouTube, from the Hootenanny to the Peoples’ Mic, the folk process, then as now, Svec argues, reclaims our humanity, reinventing media technologies to become both instruments Media as Tactical Music American Folk of resistance and fields for imagining new societies, new Folk Music selves, and new futures.‘ – Robert Cantwell, author of When We Were Good: The Folk Revival ‘Svec’s analysis of the American folk revival begins from the premise that acoustic guitars, banjos, and voices have as Tactical much to teach us about technological communication and ends, beautifully, with an uncovering of “the folk” within our contemporary media environments. What takes center stage, however, is the Hootenanny, both as it informs the author’s own folk-archaeological laboratory of imaginary media and as it continues to instantiate political community – at a Media time when the need for protest, dissent, and collectivity is particularly acute.‘ – Rita Raley, Associate Professor of English at the University of California, Santa Barbara HENRY ADAM SVEC is Assistant Professor of Communica- tion Studies at Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi. ISBN 978-94-629-8494-3 HENRY ADAM SVEC Amsterdam AUP.nl University 9 789462 984943 Press AUP_recursions.reeks_SVEC_rug11.7mm_v03.indd 1 09-11-17 14:04 American Folk Music as Tactical Media The book series Recursions: Theories of Media, Materiality, and Cultural Techniques provides a platform for cuttingedge research in the field of media culture studies with a particular focus on the cultural impact of media technology and the materialities of communication. -

California Film Institute Sponsorship Opportunities

MILL VALLEY FILM FESTIVAL | CALIFORNIA FILM INSTITUTE SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES THE CALIFORNIA FILM INSTITUTE celebrates film as art and education by presenting the annual MILL VALLEY FILM FESTIVAL, exhibiting film year-round at the non-profit CHRISTOPHER B. SMITH RAFAEL FILM CENTER, and building the next generation of filmmakers and film lovers through CFI EDUCATION. The MILL VALLEY FILM FESTIVAL is an The SMITH RAFAEL FILM CENTER is a CFI EDUCATION is building the next eleven-day celebration of the finest inde- beautifully restored Art Deco theater with generation of filmmakers and film lovers pendent and international films, tributes three screens and state-of-the-art presen- through its creative film programs which and galas. A hot stop on the Oscar® cir- tation, offering year-round programming annually serve over 8,000 students, educa- cuit, MVFF attracts the most talented and of internationally acclaimed screenings, tors, adults and families. Using film as an celebrated industry elite. The Festival an- special community events and in-person educational tool, programs reach across nually welcomes more than 200 filmmakers filmmaker appearances. In 2015, the Smith social, cultural and economic boundaries representing more than 50 countries, and Rafael Film Center welcomed 145,000 film to support and encourage youth toward hosts an audience of 68,000+ guests. lovers and 123 filmmaker guests. critical thinking, media literacy and a nuanced worldview. As a sponsor of CFI: THE RAFAEL, MVFF or CFI EDUCATION, you will contribute to the success of the mission and associate your business with distinctive and internationally recognized programs. Individual packages are designed around the unique needs of your company to more keenly focus on areas relevant to your brand such as product sampling, talent access and brand awareness, product placement, brand immersion and on-site activation. -

Actress Carey Mulligan to Receive the Artistic Achievement Award During the Centerpiece Presentation of Wildlife Costume Desi

Media Contact: Nick Harkin / Matthew Bryant Carol Fox and Associates 773.969.5033 / 773.969.5034 [email protected] [email protected] For Immediate Release: Sept. 12, 2018 ACTRESS CAREY MULLIGAN TO RECEIVE THE ARTISTIC ACHIEVEMENT AWARD DURING THE CENTERPIECE PRESENTATION OF WILDLIFE COSTUME DESIGNER RUTH CARTER (BLACK PANTHER, SELMA) TO BE HONORED WITH A CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT THIS YEAR’S BLACK PERSPECTIVES TRIBUTE The Festival will also pay tribute to the legacy of actress and Festival co-founder Colleen Moore and Chicago graphic artist Art Paul th CHICAGO – The 54 Chicago International Film Festival, presented by Cinema/Chicago, today announced Tributes to actress Carey Mulligan in conjunction with this year’s Centerpiece film Wildlife, and costume designer Ruth Carter as part of the Festival’s annual Black Perspectives Program. The Festival will also celebrate posthumously two artists special to Chicago, graphic designer Art Paul in conjunction with a screening of Jennifer Kwong’s Art Paul of Playboy: The Man Behind the Bunny, and actress and Chicago International Film Festival co-founder Colleen Moore, with a screening of The Power and the Glory (1933). The tributes will take place over the course of the Festival’s 12-day run at AMC River East 21 (322 E. Illinois St.) in Chicago, October 10-21, 2018. British actress Carey Mulligan is one of the paramount talents of her generation. Nominated for an Oscar®, a Golden Globe, and a SAG award for her radiant portrayal of the innocent teenage Jenny in An Education, Mulligan has delivered captivating performances across stage and screen, including Shame, The Great Gatsby, Inside Llewyn Davis, Mudbound, and this year’s Festival selection, Wildlife. -

William B. Kaplan CAS

Career Achievement Award Recipient William B. Kaplan CAS CAS Filmmaker Award Recipient George SPRING Clooney 2021 Overcoming Atmos Anxiety • Playing Well with Other Departments • RF in the 21st Century Remote Mixing in the Time of COVID • Return to the Golden Age of Booming Sound Ergonomics for a Long Career • The Evolution of Noise Reduction FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS NOMINEE MOTION PICTURE LIVE ACTION PRODUCTION MIXER DREW KUNIN RERECORDING MIXERS REN KLYCE, DAVID PARKER, NATHAN NANCE SCORING MIXER ALAN MEYERSON, CAS ADR MIXER CHARLEEN RICHARDSSTEEVES FOLEY MIXER SCOTT CURTIS “★★★★★. THE FILM LOOKS AND SOUNDS GORGEOUS.” THE GUARDIAN “A WORK OF DAZZLING CRAFTSMANSHIP.” THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER “A stunning and technically marvelous portrait of Golden Era Hollywood that boasts MASTERFUL SOUND DESIGN.” MIRROR CAS QUARTERLY, COVER 2 REVISION 1 NETFLIX: MANK PUB DATE: 03/15/21 BLEED: 8.625” X 11.125” TRIM: 8.375” X 10.875” INSIDE THIS ISSUE SPRING 2021 CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD RECIPIENT WILLIAM B. KAPLAN CAS | 20 DEPARTMENTS The President’s Letter | 4 From the Editor | 6 Collaborators | 8 Learn about the authors of your stories 26 34 Announcements | 10 In Remembrance | 58 Been There Done That |59 CAS members check in The Lighter Side | 61 See what your colleagues are up to 38 52 FEATURES A Brief History of Noise Reduction | 15 Remote Mixing in the Time of COVID: User Experiences | 38 RF in the Twenty-First Century |18 When mix teams and clients are apart Filmmaker Award: George Clooney | 26 Overcoming Atmos Anxiety | 42 Insight to get you on your way The 57th Annual CAS Awards Nominees for Outstanding Achievement Playing Well with Other Production in Sound Mixing for 2020 | 28 Departments | 48 The collaborative art of entertainment Outstanding Product Award Nominees| 32 Sound Ergonomics for a Long Career| 52 Return to the Golden Age Staying physically sound on the job Cover: Career Achievement Award of Booming | 34 recipient William B. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

King's Film Society Past Films 1992 –

King’s Film Society Past Films 1992 – Fall 1992 Truly, Madly, Deeply Sept. 8 Howard’s End Oct. 13 Search for Intelligent Signs of Life In the Universe Oct. 27 Europa, Europa Nov. 10 Spring 1993 A Woman’s Tale April 13 Everybody’s Fine May 4 My Father’s Glory May 11 Buried on Sunday June 8 Fall 1993 Enchanted April Oct. 5 Cinema Paradiso Oct. 26 The Long Day Closes Nov. 9 The Last Days of Chez-Nous Nov. 23 Much Ado About Nothing Dec. 7 Spring 1994 Strictly Ballroom April 12 Raise the Red Lantern April 26 Like Water for Chocolate May 24 In the Name of the Father June 14 The Joy Luck Club June 28 Fall 1994 The Wedding Banquet Sept 13 The Scent of Green Papaya Sept. 27 Widow’s Peak Oct. 9 Sirens Oct. 25 The Snapper Nov. 8 Madame Sousatzka Nov. 22 Spring 1995 Whale Music April 11 The Madness of King George April 25 Three Colors: Red May 9 To Live May 23 Hoop Dreams June 13 Priscilla: Queen of the Desert June 27 Fall 1995 Strawberry & Chocolate Sept. 26 Muriel’s Wedding Oct. 10 Burnt by the Sun Oct. 24 When Night Rain Is Falling Nov. 14 Before the Rain Nov. 28 Il Postino Dec. 12 Spring 1996 Eat Drink Man Woman March 25 The Mystery of Rampo April 9 Smoke April 23 Le Confessional May 14 A Month by the Lake May 28 Persuasion June 11 Fall 1996 Antonia’s Line Sept. 24 Cold Comfort Farm Oct. 8 Nobody Loves Me Oct. -

Inspired by the Life and Times of Woody Guthrie Saturday, October 24, 2020 7:30 PM Livestreamed from Universal Preservation Hall

This Land Sings: Inspired by the Life and Times of Woody Guthrie Saturday, October 24, 2020 7:30 PM Livestreamed from Universal Preservation Hall David Alan Miller, conductor Kara Dugan, mezzo soprano Michael Maliakel, baritone F. Murray Abraham, narrator Welcome to the Albany Symphony’s 2020-21 Season Re-Imagined! The one thing I have missed more than anything else during the past few months has been spending time with you and our brilliant Albany Symphony musicians, discovering, exploring, and celebrating great musical works together. Our musicians and I are thrilled to be back at work, bringing you established masterpieces and gorgeous new works in the comfort and convenience of your own home. Originally conceived to showcase triumph over adversity, inspired by the example of Beethoven and his big birthday in December, our season’s programming continues to shine a light on the ways musical visionaries create great art through every season of life. We hope that each program uplifts and inspires you, and brings you some respite from the day-to-day worries of this uncertain world. It is always an honor to stand before you with our extraordinarily gifted musicians, even if we are now doing it virtually. Thank you so much for being with us; we have a glorious season of life- affirming, deeply moving music ahead. David Alan Miller Heinrich Medicus Music Director This Land Sings: Inspired by the Life and Times of Woody Guthrie Saturday, October 24, 2020 | 7:30 PM Livestreamed from Universal Preservation Hall David Alan Miller, conductor Kara Dugan, mezzo soprano Michael Maliakel, baritone F. -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

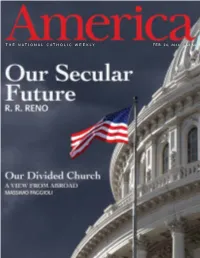

T H E N at I O N a L C at H O L I C W E E K Ly Feb. 24, 2014

THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY FEB. 24, 2014 $3.50 OF MANY THINGS Published by Jesuits of the United States state in the Abbey: it is an opportunity lived in London for nearly 106 West 56th Street three years before I set foot in for the truth of revelation to scandalize New York, NY 10019-3803 Westminster Abbey. Since the humankind’s nationalist fictions. Ph: 212-581-4640; Fax: 212-399-3596 I Yet does that happen? Throughout Subscriptions: 1-800-627-9533 16th-century English reformations, the my visit, I couldn’t help but wonder www.americamagazine.org Abbey has been the most prominent facebook.com/americamag and cherished place of worship in whether the Abbey was enacting the twitter.com/americamag the Church of England. Americans “comedy” of the city of God or the will know the Abbey from television “tragedy” of the city of man. The PRESIDENT AND EDITOR IN CHIEF coverage of the funeral of Princess monuments to the tragic figures of Matt Malone, S.J. Diana and the wedding of her son empire share cherished space with those EXECUTIVE EDITORS Prince William. The place is a curious to the equally tragic figures of a gloomy Robert C. Collins, S.J., Maurice Timothy Reidy admixture of church and state, Catholic modernity. In some ways, the Abbey has MANAGING EDITOR Kerry Weber and Protestant, self-adulation and simply swapped one metanarrative for LITERARY EDITOR Raymond A. Schroth, S.J. transcendent beauty. As a Roman another. Yet is either story truly inspired SENIOR EDITOR & CHIEF CORRESPONDENT Catholic, I experienced an unexpected, by, indeed authored by, the Gospel? I Kevin Clarke almost visceral parochial anxiety as wondered whether an ecclesial body so EDITOR AT LARGE James Martin, S.J. -

Inside Llewyn Davis Blog

DOES LLEWYN SAVE THE CAT? STC Analysis of Inside Llewyn Davis by Tom Reed The latest Coen Brothers movie has divided audiences and critics. Some call it a poetic and profound masterpiece; others find it dull, off-putting and depressing. Considering the paltry box office it’s clear mainstream moviegoers have ignored it. Along with the Academy. Why? What’s the explanation? Is this greater or lesser Coen Brothers? When I found out that a cat figured prominently in the action, I was immediately intrigued by the prospect of applying the BS2. Given the narrative prominence of a feline (an orange tabby, no less), this was a must-do. Not that I ever thought the Coens consciously applied it themselves – they’re too iconoclastic for that. They go their own way. On the other hand, they are master craftsmen at the height of their powers, which is why I was irresistibly drawn to see where and how the worlds of Blake Snyder and Joel and Ethan Coen intersected, if at all, and if that exploration could shed light on the movie and its performance. I think it can. Inside Llewyn Davis is a small, somber film, especially by mainstream standards. It feels like a character study, as Oscar Isaac, the actor portraying Llewyn, occupies virtually every frame, and doesn’t do much more than bounce around NYC looking for a place to sleep and a few bucks, playing some tunes along the way while alienating family and friends wherever he goes. Though unmistakably character-driven, it is far more than a mere character study. -

Musical Films

Musicals 42nd Street (NR) Damn Yankees (NR) 1776 (PG) A Date with Judy (NR) Across the Universe (PG-13) Deep in My Heart (NR) Alexander’s Ragtime Band (NR) De-Lovely (PG-13) All That Jazz (R) Dirty Dancing (PG-13) An American in Paris (NR) The Dolly Sisters (NR) Anchors Aweigh (NR) Dreamgirls (PG-13) Annie Get Your Gun (NR) Easter Parade (NR) The Band Wagon (NR) El Cantante (R) The Barkleys of Broadway (NR) Everyone Says I Love You (R) Begin Again (R) Evita (PG) Bells are Ringing (NR) The Fabulous Baker Boys (R) Bessie (TV-MA) Fame (1980 – R) Beyond the Sea (PG-13) Fame (2009 – PG) Blue Hawaii (PG) Fiddler on the Roof (G) The Blues Brothers (R) The Five Pennies (NR) Born to Dance (NR) Footloose (1984 – PG) Brigadoon (NR) Footloose (2011 – PG-13) The Broadway Melody (NR) For Me and My Gal (NR) Broadway Melody of 1936 (NR) Forever Plaid (G) Broadway Melody of 1938 (NR) Funny Face (NR) Broadway Melody of 1940 (NR) Funny Girl (G) Bye, Bye Birdie (G) A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Cabaret (PG) the Forum (NR) Cadillac Records (R) The Gay Divorcee (NR) Calamity Jane (NR) Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (G) Camelot (G) Get On Up (PG-13) Carmen Jones (NR) Gigi (G) Carousel (NR) The Glenn Miller Story (NR) Chicago (PG-13) Going My Way (NR) Cinderella (NR) Good News (NR) Cover Girl (NR) Grease (PG) Crazy Heart (R) Grease 2 (PG) Grease Live! (TV14) Look for the Silver Lining (NR) The Great Ziegfeld (NR) Love & Mercy (PG-13) Guys and Dolls (NR) Love Me Tender (NR) Gypsy (NR) Love’s Labour’s Lost (PG) Hair (PG) Mamma Mia! (PG-13) Hairspray (PG) Meet Me in St. -

Dr. Christopher Donovan Film Culture Associated Faculty: Professor

Film Culture Cinema 180.301 Spring 2016 Instructor: Dr. Christopher Donovan Film Culture Associated Faculty: Professor Philippe Met, Professor Lance Wahlert Film Culture Managers: Ann Molin, Michael Molisani, Emma Edoga, Breanna Himschoot Description Designed for the participants of Gregory College House’s Film Culture residential program, this course provides a flexible, immersive cinema studies experience, intended to introduce students to a wide range of films and to provide practice both speaking and writing about the art form. There are a number of weekly screening series (generally Sunday through Thursday, with some weekend events); the majority of these screenings are followed by moderated discussions. The screenings/discussions, which take place evenings in the Gregory College House cinema on the first floor of Van Pelt Manor, serve as the coursework for the class; there is no regular weekly meeting time, but rather a quota of screening attendance. To fully engage with contemporary cinema, there are also a minimum of six excursions per semester to area theatres to see and analyze contemporary releases; some past trips have included “12 Years a Slave,” “The Social Network,” “The Artist,” “Black Swan,” "The Martian," “Gravity,” “Hugo,” “Argo,” “Drive,” “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,” “Ex Machina,” “Amour,” “Foxcatcher,” “Lincoln,” “The Skin I Live In,” “Gone Girl,” "Interstellar," "Spotlight," “The Descendants,” “Holy Motors,” “Life of Pi,” “It Follows,” “Inherent Vice,” Inside Llewyn Davis,” “The White Ribbon,” “The Hunger Games” and “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire,” "Room," “A Separation,” “Blue is the Warmest Color,” “Zero Dark Thirty,” “The Hurt Locker,” “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” “The King’s Speech,” “Dallas Buyers Club” and many more.