Grappa, the Misunderstood Elixir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bigger & Bolder Stepping up Your Flavor Game in Adult Beverages

It’s all about the Flavor: Bigger & Bolder Stepping up your Flavor Game in Adult Beverages WHO’S DRINKING AND WHAT? consumed alcohol in past week Adult millennials Gen X Overall Young Millennials Adult Millennials Gen X Boomers 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Beer Cocktail/ Red wine White wine Distilled Bourbon/ Liqueur ‐ Rosé wine Sparkling Coffee Cider Brandy, mixed drink spirit ‐ neat/ whiskey ‐ neat / (blush) wine cocktail port, sherry, straight up neat/ straight up etc. straight up Note FLAVOR is most important attribute of any alcoholic beverage Most commonly mentioned hurdle to most alcoholic beverages can be the key driver of value What Does the Web say about your Brand Flavor? Latitude29 ‐ Tiki authority Beach Bum Berry’s Tiki Bar in New Orleans Are customers Do you have enough BIG FLAVOR and BIG portraying what you PRESENTATIONS to get people clicking! are about? Red Robin Got people interested with Canned Cocktails and Fun Flavored Boozy Milkshakes Serving the well balanced and Flavorful Beer cocktails in a “Can” added interest to purchase. CPK’s Strawberry Mango Cooler NAB LTO did outrageous numbers – blending beloved strawberry with other more Adventuresome Flavors such as ginger, mango, guava and finished with Fresca. Bold Flavor, light in calories …. ….Now it’s a core menu item! Safe & Familiar + Unique & Bold Flavor = Winner! FOOD & BEVERAGES WITH A FLAVORFUL STORY Having something FLAVORFUL to say Photos sell. They really do. The items that we photograph, we’ll see three times as many sales as not‐pictured items. Keith Marron, Catalina Restaurant Group January 2015 no picture picture 72 65 63 59 58 56 54 49 47 47 46 42 41 31 Combo Meal Dessert Beverage Pasta Dish Breakfast Dish App / Side Sandwich True for alcoholic beverages? no picture picture 31.6 But pictures may backfire… 27.3 BARRIO SOUR AT HARLOW (L.A.), with Tequila Cabeza, El Silencio Black Mezcal, egg white, demerara syrup and a spiced cabernet float. -

Cocktails Unlike Brandy, Which Is Distilled from Wine, Grappa Is Distilled from the “Soul of the Grape”

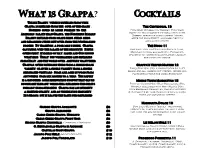

What is Grappa? Cocktails Unlike Brandy, which is distilled from wine, Grappa is distilled from the “soul of the grape”. The Centennial 13 Nothing could be more foreign to the High West Double Rye Whiskey, High West Barreled Boulevardier, Peychaud's Bitters. American palate than Grappa the Northern Italian , Stirred, served up with a cherry. Named Brandy distilled from grape skins, stems, seeds, after the Main Street landmark directly and remaining juices left over from the winemaking across the street. process. By tradition, a poor man’s drink. Grappa The Hugo 11 can pistol-whip the palate of the neophyte. Rustic, inspired from the Northern Alps of Italy, Muddled orange slices & mint, Prosecco, often fiery it smells of hay earth and God knows , , Splash of St. Germain Elderflower Liqueur- what else. Today, top winemakers and distillers served on the rocks. from Italy, and the world over, artfully craft their Grappas, often distilling them from a single grape Grappa's Vesper Martini 12 variety, or even a single variety from a single Tanqueray Gin, Stolichnaya Vodka & Lillet Blanc are all shaken, not stirred, served in a designated vineyard Some are aged in wood from . flute with a twist-The James Bond way! anywhere from six months to a year. The result is a smoother, more insinuating product that can be Mining Town Manhattan 15 downright elegant, while still retaining the spirit’s Park City's own High West Rendezvous Rye Whiskey is blended with High West's 36th primary characteristics Grappa has an intensity . , Vote Barreled Manhattan, Vermouth Rosso a pristine quality, and an underlying simplicity. -

ENOGLAM Lombardy-Veneto, Italy

ENOGLAM Lombardy-Veneto, Italy Grappa and Brandy are the most traditional of Italian spirits and represent a time- honoured custom of sharing time together after a meal with a digestif in hand. Grappa is obtained by distilling the "pomace" (or "leftovers") from the winemaking process, while Brandy is created by distilling wine. In its original version Grappa used to be clear and very strong, but in the last few years Italian distillers have moved to a more elegant and complex concept of the spirit through extended maturation in oak. In 2010 Marcello Bruschetti (owner of Enoglam) and Luciano Brotto (distiller) met and together they decided to take one step further in order to let the concept of Products Grappa evolve even further in terms of elegance and complexity. They wanted Grappa to sit at the same table as the most exclusive and famous brown spirits Dwine Brandy produced all over the world. The "Enoglam" project (which includes two brands: EVO EVO Grappa Riserva and OdeV) experimented with the use of native woods - such as Cherry, Chestnut, FUMO Grappa Riserva Beech - for longer maturation periods before bottling, and also with unusual procedures like the smoking of the pomace before distillation. The intent was to develop a spirit with a unique, strong, international personality. Today we still define these spirits as "Grappa" and "Brandy", but such definitions are far from describing their roundness, complexity, and elegance. We should probably start calling these spirits simply "EVO", making it a synonym of Italian Style in the spirits' world. "My meeting with Luciano Brotto changed my life. -

Champagne & Sparkling Wine (By the Glass) Grappa Port Wine the Bar

Champagne & Sparkling Wine (by the glass) 125ml Nyetimber, England 2010 £10.50 Taittinger, Reserve Brut NV £13.50 Taittinger Prestige Rosé NV £16.50 Taittinger, Brut Vintage 2008 £29.00 Wine (by the glass) 175ml 250ml White th Stonedale, Chenin Blanc, Western This late 17 century house, rebuilt by the Dawley £7.00 £9.50 Cape, South Africa 2013 family, stands on the cellars of an older building, the Las Boleras, Pinot Gris, Mendoza £9.00 £12.00 windows of which can be seen behind the flower Argentina 2014 Planeta, La Segreta, Grecanico, borders each side of this East exit. Prior to leaving the £8.50 £11.50 Chardonnay, Fiano, Viognier 2014 building you should notice the carvings above the Petit Chablis, Maison Olivier Tricon £12.50 £16.00 fireplace by Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721). A plaque France 2013 beside the left hand window tells of the great cedar Yealands, Sauvignon Blanc, £13.50 £17.50 Marlborough, New Zealand 2014 tree that fell in 1930 giving the name to our Cocktail Rose bar. Whilst enjoying your drink, and before the sunset, look out of the window to admire the avenue of lime Château du Donjon, Minervois, £9.00 £12.50 France 2014 trees, planted around 1716 with no other intention Red than the magnificent vista. The flavours, the views, the smell of a crackling fire, the sound of a piano and £7.00 £9.50 Primitivo, Salento, Italy, 2014 obviously good company; all is part of the Cedar Bar Tres Palacios, Merlot, Reserve, £9.00 £12.00 Maipo Valle, Chile 2012 experience. -

Grappa Cabernet

GRAPPA CABERNET E00052070 Grappa Cabernet - cl 70 Grappa is a pomace eau-de-vie, obtained by distilling fermented grape skins used in wine production. It is the most ancient and traditional distillate in Northern Italy and its name comes from “graspo”, a local name for the bunch. A symbol of man’s talent and passion, it is the heritage of peasant experience and wisdom, which transformed a solid raw material into a transparent, crystal clear liquid, rich in diverse organoleptic sensations. Grappa Alexander is the ideal meeting point between tradition and innovation, between the millenary history of this precious distillate and the evolution in its production technique, which mitigated its original harshness to make it softer, more refined and elegant. This Grappa is not for drinking, but for slow tasting, in small sips. Production Area: Veneto, Italy Vine: Pomace from Cabernet grapes Characteristics: Quality and care for the raw materials are the first and most important steps in the production of a good grappa. For this reason, healthy, fresh and vinous pomace of the vines harvested in dedicated areas are stored with care to preserve all their quality. Grappa Cabernet Alexander has its origin in the dark and rich grapes of Cabernet Franc and Cabernet Sauvignon vines, originary of Gironde, which reached Veneto at the beginning of the 20th century and became widespread leading to wines with intense color, rich in tannins and aromatic substances, with remarkable quality and longevity. Grappa is produced during three distillation phases with different temperature. The process takes place in traditional copper alembics, which allow for under vacuum distillation (greater protection of aromas), with bain-marie heating (indirect and therefore more delicate system). -

An Authentication Study on Grappa Spirit: the Use of Chemometrics to Detect a Food Fraud

Article An Authentication Study on Grappa Spirit: The Use of Chemometrics to Detect a Food Fraud Silvia Arduini 1, Alessandro Zappi 2,* , Marcello Locatelli 3 , Salvatore Sgrò 1 and Dora Melucci 2 1 Chemical Laboratory of Bologna, Anti-Fraud and Controls Office-Laboratories Section, DT VI, Italian Customs and Monopolies Agency, 40121 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (S.A.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 Department of Chemistry “Giacomo Ciamician”, University of Bologna, 40126 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Pharmacy, University “G. D’Annunzio” of Chieti-Pescara, 66100 Chieti, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: An authenticity study on Italian grape marc spirit was carried out by gas chromatography (GC) and chemometrics. A grape marc spirit produced in Italy takes the particular name of “grappa”, a product which has peculiar tradition and production in its country of origin. Therefore, the evaluation of its authenticity plays an important role for its consumption in Italy, as well as for its exportation all around the world. For the present work, 123 samples of grappa and several kinds of spirits were analyzed in their alcohol content by electronic densimetry, and in their volatile fraction by gas-chromatography with a flame-ionization detector. Part of these samples (94) was employed as a training set to compute a chemometric model (by linear discriminant analysis, LDA) and the other part (29 samples) was used as a test set to validate it. Finally, two grappa samples seized from the Citation: Arduini, S.; Zappi, A.; market by the Italian Customs and Monopolies Agency and considered suspicious due to their aroma Locatelli, M.; Sgrò, S.; Melucci, D. -

Consuming Alcohol on a Gluten Free Diet

Presents… It should be noted that distilled alcoholic spirits (hard liquors) are considered gluten free by the manufacturers. The claim is that distillation eliminates any gluten in the beverage. Gluten Free Society does not recommend the consumption of any spirit derived from grain regardless of manufacturer claims. Drink at your own risk!!! Alcohol is generally not recommended because common consumption is not healthy regardless of gluten status. Many advocate the intake of wine as a heart disease preventative. Gluten Free Society does not recommend daily use of any alcoholic beverage. Remember that gluten sensitivity causes liver damage as does alcohol intake. Beer, meads, and ales Wine Wine Coolers Brandy Champagne Cider Cognac Malted beverages Grappa Ouzo Rum Sake Schnapps Tequila Vodka Whiskey Beer is typically brewed using grain. Many beers labeled “gluten free” use sorghum, millet, buckwheat, and brown rice as a substitute for wheat and barley. As sorghum, millet, and rice contain glutens, these beers are not recommended. Drink at your own risk!! Wine and champagne are produced from grapes. Typically wine is safe on a gluten free diet, but it is recommended that you check with the manufacturer to make sure no gluten has been added. Wine coolers are NOT gluten free as they contain barley malt. Brandy is distilled from fruit. Most commonly used are pears, cherries, peaches, and raspberries. It is safe on a gluten free diet. Cider is generally made from the fermented juice of apples. The juice is typically fermented in oak barrels by adding yeast. It has a higher alcoholic content than beer (5% or greater). -

Peruvian Pisco Grappa

UNIT 2 2 Lesson 6: Peruvian pisco vs. Grappa Peruvian pisco Grappa Must rest in neutral casks Can be bottled after Aging a minimum of 3 months. distillation or aged in barrels. Only wine is distilled. Skins, pips A pomace brandy. The fermented skins, Use of stalks are discarded before seeds and stalks leftover from distillation. No water allowed. winemaking are distilled. No water pomace allowed. UNIT 1 2 Lesson 6: Peruvian pisco vs. Grappa Pomace/Marc UNIT 2 2 Lesson 6: Peruvian pisco vs. Grappa ● Peruvian pisco is usually distilled with a copper pot, direct flame heated. Sometimes a falca still is used. ● Grappa is distilled using double boiler (bain-marie) or steam distillation to prevent burning. ● Grappa is watered down after distillation to reach desired proof. Distilling grappa UNIT 2 2 Lesson 6: Peruvian pisco vs. Grappa Peruvian pisco Grappa Regions Made in one of the 5 pisco Made from Italian grapes & distilled in regions, from grapes grown in Italy, the Italian part of Switzerland or those regions. San Marino. Grape Made from any of the 8 Made from any grape varieties permitted by the variety used in wine-making. s D.O. in Peru. UNIT 2 2 Lesson 6: Peruvian pisco vs. Grappa Peruvian pisco Grappa Flavoring No flavoring or infusions Allows for flavoring or allowed during infusions production. post-distillation. Classifications None Classified according to its age, the grape or grapes from which the marc was obtained and, sometimes, the essences used to flavor it. UNIT 2 2 Lesson 6: Peruvian pisco vs. Grappa Grappa is classified according to its age, the grape or grapes from which the marc was obtained and, sometimes, the essences used to flavor it. -

Spirits Menu

SPIRITS VODKA RYE Belvedere ……………………..…………….13 Bulliet…………………………………….….12 Chopin ……………..………………………..13 High West Double Rye………………….…14 Ciroc ………………………..………………..11 High West Rendezvous Rye…………….…22 Grey Goose Orange………………..………12 Knob Creek …………………………………12 Grey Goose ……………….………….……..12 Micther’s ………………………………….…16 Hanger One…….……………………………12 Pikesville ………………………………….…16 Kettle One Citron.….……………………….12 Rittenhouse …………………………….…..10 Ketel One…………………………………….12 Russels..………………………………….…..13 Square One Cucumber.……………………12 Templeton 4yr ………………………….…..10 Titos………………………………………….10 Tin Cup ………………………………….…..12 Vanilla Stoli………………………………….10 Savage and Cook “Lip Service” ……….…15 Sazerac ………………………………….…..12 BOURBON Whistle Pig 6 Year Piggy Back…………….16 Basil Haden’s ……..…………………..….…16 Blanton’s…………………………………..…18 IRISH/CANADIAN Booker’s ………………………………….… 22 Jameson…………………………………..…10 Buffalo Trace ……………………………..…10 Green Spot…………………………………..18 Bulliet …………………………………….….12 Redbreast 12yr………………………………19 Colonel E.H. Taylor Single Barrel …….…..20 Crown Royal…………………………………10 Colonel E.H. Taylor Small Batch ……….…18 Eagle Rare……………………………………14 JAPANESE Elijah Craig Small Batch ……………….…..18 Akashi……………………………………..…14 Four Roses Single Barrel ………….…….…14 Kaiyo……………………………………….…20 Hanckocks……………………………………24 Nobushi………………………………………16 High West American Prairie ………..…….12 Knob Creek……………………………….…14 SINGLE MALT SCOTCH Larceny………………………………….……12 Balvenie 14yr Caribbean Cask……………19 Maker’s Mark ………………………….……12 Dalwhinnie 15yr………………………….…18 Michter’s ………………………………….…16 Glenfiddich 15yr -

Day Drinks D&Co 06.18.2020

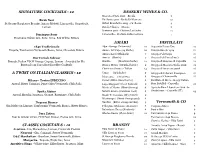

SIGNATURE COCKTAILS • 12 DESSERT WINES & CO. Moscato D’Asti 2015 - Braida 8 Birds Nest Vin Santo 2011 - Badia Di Morrona 10 St.George Raspberry Brandy, Amaro Meletti, Limoncello, Grapefruit, Birbet Bracchetto 2013 - Ca’ Rossa 8 Lemon Barolo Chinato - Mossio 8 Sauterne 2011 - Chateau Laribotte 11 Piucinque Sour Limoncello - Profumi Della Costiera 7 Piucinque Italian Gin, Suze, Lime, Egg White, Bitters AMARI DISTILLATI 1840 Tradizionale Alpe - Genepy (Artemisia) 10 Acquavite Prime Uve 12 Tequila, Tamburnin Vermouth Rosso, Lime, Chocolate Bitters Amaro Del Capo (29 Herbs) 10 Grappa Barolo 1984 18 Amaro Zarri (Rhubarb) 7 Grappa Poli Sarpa 15 Our French Sidecar Averna (Myrtle) 9 Grappa Poli Pera (Pear) 16 Brandy, Italian VSOP Orange Cognac, Lemon - Awarded by Ms. Braulio (Mountain herbs) 12 Grappa di Bassano di Capovilla 12 Barstool’s on Top 5 Best East Bay Cocktails Branca Menta (Menthol-bitter) 9 Grappa di Moscato Giallo 2010 19 Chartruse Green or Yellow 14 Grappa di Amarone 2008 16 A TWIST ON ITALIAN CLASSICS • 12 Cynar (Artichoke) 8 Grappa di Cabernet Sauvignon 15 Disaronno (Amaretto) 8 Grappa of Chamomille 15 Milano - Torino INDECISO Fernet (Bitter-Sweet herbs) 8 Distillato di Birra - Hoppy Italian Aperol, Bitter Campari, Punt e Mes Vermouth, Club Soda Lago Maggiore (Clove-Saffron) 9 Beer Distilled - Capovilla 20 Maria al Monte (Mint-Ginseng) 8 Agricole Rum Liberation 2010 de Spritz Alpino Meletti Amaro (Genziana root) 8 Guadeloupe - Capovilla (IT) 23 Aperol, Braulio, Prosecco, Orange, Rosemary, Club Soda Monte S. Costanzo (Dry Fernet) -

Wine List Grap

ER, N EST Y H C O R PA WINE LIST GRAP U A E V U I O TA L I A N N • BY THE GLASS• WHITE LAMBERTI • Prosecco NV • Veneto, Italy 9 • 36 ROSATELLO • Moscato NV • Provincia di Pavia, Italy 9 • 36 LAURENT MIQUEL • Albarino 2018 • Lagrasse, France 9 • 36 KIM CRAWFORD • Sauvignon Blanc 2018 • Marlborough, New Zealand 12 • 48 MEIOMI • Chardonnay 2017 • California 12 • 48 LUCIEN ALBRECHT • Gewürztraminer Reserve 2017 • Alsace, France 14 • 56 OLIVIER LEFLAIVE • Bourgogne Blanc “les Sétilles” • Burgundy, France 14 • 56 RED DREAMING TREE • “Crush” Red Blend 2017 • California 10 • 40 VIÑA BUJÁNDA • Tempranillo Crianza DOC 2016 • Rioja, Spain 10 • 40 TENUTA REGALEALI • Nero D’Avola DOC 2017 • Sicily, Italy 12 • 48 MARCHESI DI GRÉSY • Dolcetto d’Alba “Monte Aribaldo” DOC 2017 • Piedmont, Italy 12 • 48 LULI • Pinot Noir 2017 • Santa Lucia Highlands, California 15 • 56 SMITH & HOOK • Cabernet Sauvignon 2017 • Central Coast, California 15 • 56 EL ESTECO • Malbec 2016 • Calchaquí Valley, Argentina 15 • 56 • BY THE BOTTLE• WHITE ROYAL TOKAJI (500 ml) • Late Harvest White Blend 2016 • Tokaj, Hungary 36 LAMOREAUX LANDING • Semi-Dry Riesling 2017 • Finger Lakes, New York 30 TENUTA CARRETTA • Roero Arneis ‘Cayega’ DOCG 2014 • Piobesi d’Alba, Italy 40 RE MANFREDI • Bianco Basilicata IGT 2017 • Venosa, Italy 40 BOTTEGA VINAIA ESTATE • Pinot Grigio DOC 2018 • Trentino, Italy 30 STADT KREMS • Grüner Veltliner 2017 • Kremstal, Austria 42 WISEGUY • Sauvignon Blanc 2016 • Yakima Valley, Washington 40 LOUIS JADOT • Pouilly-Fuissé 2017 • Burgundy, France 56 ROMBAUER • -

Dessert Beverage Amari Grappa Dolci D

DESSERT BEVERAGE DESSERT BEVERAGE Corvina Blend 2010 David Sterza Recioto 15 Corvina Blend 2010 David Sterza Recioto 15 Valpolicella, Veneto Valpolicella, Veneto Zibibbo 2015 Donnafugata ‘Ben Rye’ 19 Zibibbo 2015 Donnafugata ‘Ben Rye’ 19 Passito di Pantelleria, Sicilia Passito di Pantelleria, Sicilia Myrtle Berry NV Tremontis ‘Mirto’ 12 Myrtle Berry NV Tremontis ‘Mirto’ 12 Sardegna Sardegna Red Eye Rye 11 Red Eye Rye 11 coffee infused rye whiskey try on the rocks coffee infused rye whiskey try on the rocks DOLCI DOLCI PEAR CROSTATA 10 PEAR CROSTATA 10 pear, hazelnut, ginger, honey, thyme pear, hazelnut, ginger, honey, thyme TORTA DI CIOCCOLATO 10 TORTA DI CIOCCOLATO 10 chocolate mousse, cherry cream, red wine sauce chocolate mousse, cherry cream, red wine sauce PEACH PANNA COTTA 10 PEACH PANNA COTTA 10 bellini mezzo, raspberry coulis, biscotto al burro bellini mezzo, raspberry coulis, biscotto al burro GELATO OR SORBETTO FLIGHT 7 GELATO OR SORBETTO FLIGHT 7 seasonal seasonal AMARI 9 AMARI 9 HOUSE FLIGHT 12 | CUSTOM FLIGHT 15 HOUSE FLIGHT 12 | CUSTOM FLIGHT 15 Bosca ‘Cardamaro’ moscato infused with cardoons & blessed thistle Bosca ‘Cardamaro’ moscato infused with cardoons & blessed thistle Nonino ‘Quintessentia’ grape distillate blended with amaro Nonino ‘Quintessentia’ grape distillate blended with amaro Averna herbs, roots, citrus rind Averna herbs, roots, citrus rind Tempus Fugit ‘Gran Classico’ rhubarb, gentian, orange peel Tempus Fugit ‘Gran Classico’ rhubarb, gentian, orange peel Tosolini rosemary, star anise, coffee Tosolini rosemary,