The Deprivatization of Art: Dan Graham As an Art Worker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Dan Graham: Mirror Complexities Border Crossings

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Dan Graham: Mirror Complexities By Robert Enright and Meeka Walsh (Winter 2009) Public Space/Two Audiences, 1976. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York “I like to get into new areas,” Dan Graham says in the following interview, “and I like them to be in a borderline situation, rather than definitively one thing.” For over 50 years, Graham has located himself in a number of borderline situations, and from that position of in-betweenness has made an art of perplexing simplicity. Critics generally assign his Schema, 1966, a series of instructional sheets that gave editors sets of data for the composition of printed pages, a generative place in the history of conceptual art. But the various Schema were themselves in border zones of their own, part poetry, part criticism, part visual art. Their newness was in their indeterminacy. Similarly, the deliberately uninflected and abstract photographs he took in 1966 of tract houses, storage tanks, warehouses, motels, trucks and restaurants, subjects he passed in the train on his way into New York from the suburbs, occupied two zones in his mind. In his own estimation, he was “trying to make Donald Judds in photographs.” His first pavilions, beginning with Public Space/Two Audiences made for the Venice Biennale in 1976, were a cross between architecture and sculpture. His cross-disciplinary mobility functioned in all directions: Sol LeWitt’s early sculptures encouraged Graham’s interest in urbanism because the sculptures seemed to him to be about city grids. It’s because of this overall sense of one category of art drifting into another that Graham says, “all my work is a hybrid.” His idea of hybridity was predicated upon an intense degree of experiential involvement; in performance/video works like Nude Two Consciousness Projection(s), 1975, and Intention Intentionality Sequence, 1972, the audience was part of the performance; just as audience involvement was also critical in a number of the pavilions. -

Press Release

Press Release Dan Graham Rock ‘n’ Roll 3 October – 3 November 2018 27 Bell Street, London Opening: 2 October, 6 – 8pm For his tenth exhibition with Lisson Gallery, Dan Graham draws on his long-standing history working with music and performance to present a new stage-set design, alongside over-sized models, video and a courtyard pavilion, exploring the relationship between audience and performer. Based in New York, Graham is an icon of Conceptual art, emerging in the 1960s alongside artists such as Dan Flavin, Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt. A hybrid artist, he has been at the forefront of many of the most significant artistic developments of the last half-century, including site-specific sculpture, video and film installation, conceptual and performance art, as well as social and cultural analysis through his extensive writings. Delving into the performative in the early 1970s – exploring shifts in individual and group consciousness, and the limits of public and private space – Graham’s practice evolved into the installations and pavilions for which he is famous internationally. Today, his work continues to evolve with the world around it, taking on a different reading in the age of social media, photography and obsessive self-documentation. A recent work such as Child’s Play (2015-2016), which was on display recently in Museum of Modern Art’s Sculpture Garden, is from a group of works that Graham describes as fun houses for children and photo ops for parents. The artist’s latest presentation of work focuses on the relationship between musical performance and audience. The space at 27 Bell Street will be occupied by a curvilinear stage-set which visitors will be able to walk around. -

GNR SP | Dan Graham | Preview with Installs | EN.Indd

exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 exhibition view, galeria nara roesler | são paulo, 2017 Galeria Nara Roesler | São Paulo is pleased to present a solo exhibition of Dan Graham’s works (b. Urbana, IL, USA, 1942), on view August 12 through November 12, 2017. The first exhibition of Graham’s work at Galeria Nara Roesler features Pavilion (2016), a new work created specifically for the occasion, in addition to six untitled maquettes (2011–2016) and the video work Death by Chocolate: West Edmonton Shopping Mall (1986–2005). Parallel to the exhibition, the Museum of Image and Sound will screen two of the artist’s emblematic video works: Rock My Religion (1982–1984) and Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30 (2004). Presented in collaboration with Galeria Nara Roesler, the screenings will take place at the museum on Sunday, August 13, at 4pm, followed by a roundtable with guests including Marta Bogéa, Agnaldo Farias and Solange Farkas, who will engage in a discussion about Graham’s works, also at the Museum. Untitled, 2016 2-way mirror glass, aluminium, MDF and acrylic ed 1/3 42 x 107 x 125 cm Sem Título, 2016 2-way mirror glass, aluminium, MDF and acrylic 42 x 107 x 125 cm Untitled, 2011 2-way mirror glass, aluminium, MDF and acrylic ed 1/3 71 x 107 x 107 cm Exhibited across the globe, Dan Graham’s pavilions are emblematic of his critical engagement with the visual and cognitive parameters of architectural language within and outside of art institutions. -

Press Dan Graham: Whitney Museum of American Art Artforum, October

MARIAN GOODMAN GALLERY Dan Graham: WHITNEY MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART By Hal Foster (October 2009) OF ACTIVE ARTISTS over the age of sixty in the United States, Dan Graham may be the most admired figure among younger practitioners. Though never as famous as his peers Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, and Bruce Nauman, Graham has now gained, as artist-critic John Miller puts it, a “retrospective public.” Why might this be so? “Dan Graham: Beyond,” the excellent survey curated by Bennett Simpson of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (the show’s inaugural venue), and Chrissie Iles of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, offers ample reasons. If Minimalism was a crux in postwar art, a final closing of the modernist paradigm of autonomous painting and a definitive opening of practices involving actual bodies in social spaces, its potential still had to be activated, and with his colleagues Graham did just that. (This moment is nicely narrated by Rhea Anastas in the catalogue for the show.) “All my work is a critique of Minimal art,” Graham states (in an intriguing interview with artist Rodney Graham also in the catalogue); “it begins with Minimal art, but it’s about spectators observing themselves as they’re observed by other people.” Hence many of the forms associated with his work: interactions between two performers; performances by the artist that directly engage audiences; films and videos reflexive about the space of their making; installations involving viewers in partitions, mirrors, and/or videos; architectural models; and pavilions of translucent and reflective glass. -

WHITNEY BIENNIAL 2006: DAY for NIGHT to OPEN Signature Survey Measuring the Mood of Contemporary American Art, March 2-May 28, 2006

Press Release Contact: Jan Rothschild, Stephen Soba, Meghan Bullock (212) 570-3633 or [email protected] www.whitney.org/press February 2006 WHITNEY BIENNIAL 2006: DAY FOR NIGHT TO OPEN Signature survey measuring the mood of contemporary American art, March 2-May 28, 2006 Peter Doig, Day for Night, 2005. Private Collection; courtesy Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin. The curators have announced their selection of artists for the 2006 Whitney Biennial, which opens to the public on March 2, and remains on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through May 28, 2006. The list of participating artists appears at the end of this release. Whitney Biennial 2006: Day for Night is curated by Chrissie Iles, the Whitney’s Anne & Joel Ehrenkranz Curator, and Philippe Vergne, the Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The Biennial’s lead sponsor is Altria. "Altria Group, Inc. is proud to continue its forty year relationship with the Whitney Museum of American Art by sponsoring the 2006 Biennial exhibition," remarked Jennifer P. Goodale, Vice President, Contributions, Altria Corporate Services, Inc. "This signature exhibition of some of the most bold and inspired work coming from artists' studios reflects our company's philosophy of supporting innovation, creativity and diversity in the arts." Whitney Biennial 2006: Day for Night takes its title from the 1973 François Truffaut film, whose original French name, La Nuit américaine, denotes the cinematic technique of shooting night scenes artificially during the day, using a special filter. This is the first Whitney Biennial to have a title attached to it. -

Dan Graham Nuggets New and Old Writing on Art, Architecture, And

Dan Graham Critical dialogues Nuggets Dan Graham (born in 1942, lives in New York City), began directing the New and Old Writing John Daniels Gallery (NY) in 1964, where he put on Sol LeWitt's first one-man show. In the group shows he organized he exhibited the works on Art, Architecture, of Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, and Robert Smithson. Like these artists, Graham considered himself a writer-artist, publishing essays and and Culture reviews on rock music, Eisenhower's paintings, and Dean Martin's television show. His earliest work dealt with the magazine page, and one Program of his seminal early works was a series of magazine-style photographs Positions Series with text, “Homes for America” (1966–1967). Focusing on cultural ______________________________________ phenomena, and incorporating photography, video, performance, glass Edited by and mirror structures, Dan Graham's practice has become a key part of Kathy Slade the Conceptual art canon. He is a highly influential figure in the field of ______________________________________ contemporary art, both as a practitioner and as a well-respected critic and theorist. Authors Dan Graham This volume brings together texts written on various artists he admires, ______________________________________ as well as interviews collected since the 1990s, most notably on his Edition large-scale installations incorporating mirrors—a culmination of his long English examination of the psychological relationship between people and December 2013 architecture. ISBN: 978-3-03764-198-9 Softcover, 150 x 210 mm This book is part of the “Positions” series, co-published with Les 160 pages presses du réel and dedicated to artists' writings. Images 17 b/w CHF 20 / EUR 15 / £ 12.95 / US Co-published with ECU Press, Vancouver. -

John Chamberlain

John Chamberlain John Chamberlain was born in 1927 in Rochester, Indiana. He grew up in 1. Luftschloss, 1979 10. Gondola T. S. Eliot, 1981 Chicago and, after serving in the United States Navy from 1943 to 1946, he Painted and chromium-plated steel Painted steel attended the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 1950s. In 1955 and 1956, 2. The Hot Lady from Bristol, 1979 11. Gondola W. H. Auden, 1981 Painted steel Chamberlain studied and taught sculpture at Black Mountain College, near Painted and chromium-plated steel Asheville, North Carolina. He moved to New York in 1956 and the following 3. American Barge, 1979 12. Daddy in the Dark, 1988 Urethane foam and canvas Painted and chromium-plated steel year made Shortstop, his first sculpture incorporating scrap metal from cars. Collection Louise and Leonard Riggio Chamberlain’s first major solo show was presented at the Martha Jackson 4. Black Cherry-No-Cal, 1971 Videotapes transferred to digital files, 13. Black Satin Custard, 1980 Art of Assemblage Gallery, New York, in 1960. His work was included in the black-and white, sound Painted and chromium-plated steel exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1961, and he began Courtesy Castelli Gallery, New York 14. Chickmeat, 1979 showing at Leo Castelli’s New York gallery in 1962. Chamberlain had his first 5. Hit Height Lear, 1979 Painted and chromium-plated steel Painted and chromium-plated steel retrospective in 1971 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and 15. Thordis’ Barge, 1980–81 the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, held a second retrospective 6. -

Graham, New American Film and Video Series”, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Dan Graham b. 1942 Urbana, Illinois Awards 1992 Coutts Contemporary Art Foundation Award Skowgenen Award 1993 City of Nantes Solo Exhibitions 1969 John Daniels Gallery, New York City 1970-71 Anna Leonowens Gallery, Nova Scotia College of Art, Halifax The Mezzanine, Nova Scotia College of Art, Halifax 1972 Fourth Floor Gallery, Halifax, Nova Scotia Lisson Gallery, London (exh cat) Protech-Rivkin Gallery, Washington DC Galleria Toselli, Milan Project Inc, Cambridge, Massachusetts Gallery A 402, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California 1973 Galerie MTL, Brussels Galerie Zwirner, Cologne Galleria Schema, Florence Gallery A 402, Institute of Arts, Valencia 1974 Galleria Marilena Bonomo, Bari, Italy Galerie 17, Paris Royal College of Art, London Lisson Gallery, London Galerie MTL, Brussels Epson School of Art, ‘Performance and Films’, Surrey 1975 Modern Art Agency, Naples John Gibson Gallery, New York Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels Internationaal Cultureel Centrum, Antwerp Griffiths Art Centre, St Lawrence University, Canton, New York Otis Institute Gallery (with Mowry Baden), Los Angeles 1976 Sperone Westwater Fischer, New York Salle Patino, Geneva, Switzerland (exh cat) Samangallery, Genoa Galerie Vega, Liege, Belgium New Gallery, ICA, London Anne-Marie Verna, Zürich Galleria Banco, Brescia Kunsthalle Basel, Switzerland (exh cat) 1977 "Video Piece for two Glass Buildings", Leeds Polytechnic Gallery Rene Block Galerie, Berlin "Articles", Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven (exh cat) Studio Terelli, Ferrara Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, -

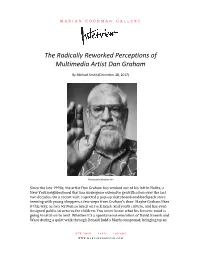

The Radically Reworked Perceptions of Multimedia Artist Dan Graham

The Radically Reworked Perceptions of Multimedia Artist Dan Graham By Michael Smith (December 28, 2017) Photography Sebastian Kim Since the late 1990s, the artist Dan Graham has worked out of his loft in Nolita, a New York neighborhood that has undergone extensive gentrification over the last two decades. On a recent visit, I spotted a pop-up skateboard-and-backpack store teeming with young shoppers a few steps from Graham’s door. Maybe Graham likes it this way, as he’s written so much on rock music and youth culture, and has even designed public structures for children. You never know what his frenetic mind is going to latch on to next. Whether it’s a spontaneous evocation of David Koresh and Waco during a quiet walk through Donald Judd’s Marfa compound; bringing up an anecdote at the most inappropriate moment; or his amazing, almost encyclopedic recall of information that would give most savants a run for their money, Graham, now 75, never ceases to surprise. He’s deeply into astrology. Anyone who meets him almost always enters into his constellation of astrological annotations. He’s an Aries, indicating spontaneity. He’s also into clichés, architecture, music, art, puppets, mixtapes, and TV comedy. I’ve known Graham since the mid-’80s, when the art world was a much smaller place. Today, of course, most people know Graham as an icon, the quintessential hybrid artist whose practice has encompassed a range of media, disciplines, and contexts, including video art (of which he was an early pioneer), architecture, performance, photography, literature, and most notably, a series of steel-and-glass pavilions. -

Dan Graham Lives and Works in New York, NY, USA 1942 Born in Urbana, IL, USA Selected Solo Exhibitions 2019 Francesca Minini

Dan Graham Lives and works in New York, NY, USA 1942 Born in Urbana, IL, USA Selected Solo Exhibitions 2019 Francesca Minini, Milan, Italy 2018 ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll’, Lisson Gallery, London, UK ‘Beyond Walls’, Sirius Arts Centre, County Cork, Ireland ‘New Works By A Small-Town Boy’, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, USA ‘TV Producer as Conceptual Artist’, Greene Naftali, New York, USA 2017 ‘Greatest Hits’, Red Brick Museum, Beijing, China ‘Works That Are Fun For The Family’, Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, Croatia ‘Dan Graham’, Nara Roesler Gallery, São Paulo, Brazil 2016 ‘Dan Graham/Rocks’, Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio, USA ‘Dan Graham: Pavilion Compilation’, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio, USA ‘Dan Graham’, Filomena Soares Gallery, Lisbon, Portugal 2015 ‘Observatory/Playground’, MAMO, Marseille, France ‘Models for Pavilions’, ETH Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland ‘Dan Graham’, Massimo Minini, Brescia, Italy ‘Dan Graham: Two Cubes, One Rotated 45°’, Marian Goodman, Paris, France ‘Dan Graham – Sculpture Or Pavilion?’, Micheline Szwajcer Gallery, Antwerp, Belgium 2014 ‘Photos, Videos and Pavilion’, De Pont Museum, Tilburg, Netherlands Greene Naftali, New York, NY, USA ‘Tunnel of Love’, Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen, Denmark ‘Rock My Religion’, Shaker Museum Mount Lebanon, New York, NY, USA ‘Art as Design/Design as Art’ (with Heimo Zobernig), Galerie Christine Mayer, Munich, Germany ‘The Roof Garden Commission’ (with Günther Vogt), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA 2013 ‘Two Cubes, One Rotated 45°’, Turner Contemporary, Margate, UK ‘Past Future Split Attention’, Manchester International Festival, Manchester, UK 2012 ‘Rock n’ Roll Show: Unrealised Projects for Children and Boutique Architecture’, Hauser & Wirth, Zurich, Switzerland ‘Pavilions’, Lisson Gallery London, UK Johnen Galerie, Berlin, Germany 2011 ‘Models and Videos’, Eastside Projects, Birmingham, UK ‘Exposition d’overture’, Le Consortium, Dijon, France ‘Through the Looking Brain: A Swiss Collection of Conceptual Photography’, Kunstmuseum Sankt Gallen, St. -

Bringing People Together Through Interactive Artworks: an Interview with Jeppe Hein – Urban Times 24.11.2014 13:11

Bringing People Together Through Interactive Artworks: An Interview With Jeppe Hein – Urban Times 24.11.2014 13:11 Bringing People Together Through Interactive Artworks: An Interview With Jeppe Hein 3rd November 2014 Thejas Jagannath ! 1174 points • 132 posts Learn more about Jeppe Hein's transforming artwork in this interview! more info " This is a community post, untouched by our editors. Jeppe Hein has produced many experiential artworks. He bases his artworks on interactive and community oriented features. Jeppe Hein is a famous artist based in Berlin and Copenhagen. He has produced artworks that have been showcased around the world. For instance, appearing rooms which is a water fountain at The South Bank Centre, London has become very successful and popular among residents. He also experiments with mirror and minimalist/conceptual art forms which gives people a reason to connect and draw meaning from his art. He has also contributed a lot to public art as his artworks are usually featured in public spaces. This makes them more accessible so that everyone can enjoy them in the urban realm. https://urbantimes.co/2014/11/bringing-people-together-through-interactive-artworks-an-interview-with-jeppe-hein/ Seite 1 von 29 Bringing People Together Through Interactive Artworks: An Interview With Jeppe Hein – Urban Times 24.11.2014 13:11 I had the opportunity to interview Jeppe Hein. In this interview, he provides some great insights into his artworks, why he makes them interactive and public, and the things we can expect to see from him in the future. Take a look at our conversation below: Thejas: Why do you choose to make your sculptures interactive to the public? Jeppe: In my view, the concept of sculpture is closely linked to communication. -

Dan Graham Transcript

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: DAN GRAHAM, Artist INTERVIEWER: SABINE BREITWIESER, MoMA Chief Curator of Media and Performance Art LOCATION: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART DATE: NOVEMBER 1, 2011 TRANSCRIBER: Janet Crowley, Transcription Completed November 15, 2011 [Crew Discussion] SB: Hi, Dan, hello. I was asked to say the day of today. It’s November the first, 2011, and we are at The Museum of Modern Art on 11 West 53rd Street at the Drawing Study Center. I am Sabine Breitweiser, Chief Curator of Media and Performance Art, talking to artist Dan Graham. Do you want to introduce yourself? DG: Yes. I actually think of myself as more of a writer than an artist, and I don’t think of myself as an architect, but my work is always a hybrid. So I began with magazines, magazine articles and pages. SB: Okay, Dan. You usually start a conversation talking about someone’s zodiac, so I thought that might be a good point to start today. [0:05:17] DG: That’s for picking up women. [laughter] SB: That’s for picking up women, so pick me up. [laughing] So, you’re an Aries, and you recently sent me your zodiac description where you introduced yourself as being a pioneer, re-inventing, constantly yourself. DG: Well, I wouldn’t say that. I would just say that I admire, among the politicians, Kruschev, who was an Aries, who de-Stalinized Russia. And also his son is a very famous American computer scientist. But in terms of the zodiac, my birthday is MoMA Archives Oral History: D.