Downloads Charts, It Is No Longer Possible to Define Culture in Opposition to the Marketplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT of GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected]

BIRGIT TAUTZ DEPARTMENT OF GERMAN Bowdoin College 7700 College Station, Brunswick, ME, 04011-8477, Tel.: (207) 798 7079 [email protected] POSITIONS Bowdoin College George Taylor Files Professor of Modern Languages, 07/2017 – present Assistant (2002), Associate (2007), Full Professor (2016) in the Department of German, 2002 – present Affiliate Professor, Program in Cinema Studies, 2012 – present Chair of German, 2008 – 2011, fall 2012, 2014 – 2017, 2019 – Acting Chair of Film Studies, 2010 – 2011 Lawrence University Assistant Professor of German, 1998 – 2002 St. Olaf College Visiting Instructor/Assistant Professor, 1997 – 1998 EDUCATION Ph.D. German, Comparative Literature, University of MN, Minneapolis, 1998 M.A. German, University of WI, Madison, 1992 Diplomgermanistik University of Leipzig, Germany, 1991 RESEARCH Books (*peer-review; +editorial board review) 1. Translating the World: Toward a New History of German Literature around 1800, University Park: Penn State UP, 2018; paperback December 2018, also as e-book.* Winner of the SAMLA Studies Book Award – Monograph, 2019 Shortlisted for the Kenshur Prize for the Best Book in Eighteenth-Century Studies, 2019 [reviewed in Choice Jan. 2018; German Quarterly 91.3 (2018) 337-339; The Modern Language Review 113.4 (2018): 297-299; German Studies Review 42.1(2-19): 151-153; Comparative Literary Studies 56.1 (2019): e25-e27, online; Eighteenth Century Studies 52.3 (2019) 371-373; MLQ (2019)80.2: 227-229.; Seminar (2019) 3: 298-301; Lessing Yearbook XLVI (2019): 208-210] 2. Reading and Seeing Ethnic Differences in the Enlightenment: From China to Africa New York: Palgrave, 2007; available as e-book, including by chapter, and paperback.* unofficial Finalist DAAD/GSA Book Prize 2008 [reviewed in Choice Nov. -

Date of Birth 21.02.1981 Place of Birth Göttingen, Germany

CURRICULUM VITAE PD DR. ANNA-LISA MÜLLER PERSONAL INFORMATION Date of birth 21.02.1981 Place of birth Göttingen, Germany SCIENTIFIC CAREER Since Nov. 2020 Deputy Head of the Working Group Human Geography University of Heidelberg, Germany 2019–2020 Senior Researcher Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies (IMIS), University of Osnabrück, Germany 2019 Habilitation, venia legendi “Humangeographie” Department of Geography, University of Bremen, Germany 2013–2019 Senior Researcher Department of Geography, University of Bremen, Germany 2–4/2017 Visiting Academic Durham University, UK 2013 PhD, grade “summa cum laude” Bielefeld University, Germany 2012–2013 Research Assistant Research Group Urban Metamorphoses, HafenCity University Hamburg, Germany PD DR. ANNA-LISA MÜLLER | CV | 1/25 2010–2012 Graduate Student & PhD candidate Bielefeld Graduate School in History and Sociology, Bielefeld University, Germany title of PhD thesis: Green Creative Cities. Designing a New Type of Cities of the 21st Century (in German) 2007–2010 Research Assistant Center of Excellence 16 Cultural Foundations of Integration, Department of Sociology, chair of Prof. Dr. Andreas Reckwitz, University of Konstanz, Germany 10/2004–6/2007 Graduate studies in sociology, German literature and philosophy (Magister-Hauptstudium), University of Konstanz, Germany; grade: “very good”, title of Master's thesis: “Subject, Language and Power in the Work of Judith Butler” 9/2003–7/2004 Undergraduate studies in sociology, University of Växjö, Sweden 10/2001–3/2003 Undergraduate -

Hwa-Byung:The

FROM THE INSTRUCTOR In his prize-winning essay, “Hwa-Byung: The “Han”-Blessed Illness,” Wooyoung Cho taps a global skill set to shed new light on how culture shapes definitions of mental illness. His paper is an outstanding example of student-driven inquiry. I had never heard of the Korean culture-bound mental illness called hwa-byung when Wooyoung proposed this project. But even if I had, I would’ve had no idea where to find narratives about hwa-byung written by young men, let alone be able to translate them from Korean. (Are you curious yet?) In his research, Wooyoung learned that scholarly studies of hwa-byung have focused on middle-aged women and interpreted their symptoms as reflections of Korea’s patriarchal social structure. When he discovered that today more young men are being diagnosed with hwa-byung, he wanted to understand the social causes of their distress. One way he gathered evidence was by searching a Korean online forum and reading posts by young men about their hwa-byung experiences. When students in Marisa Milanese’s “Global Documentary” class read a draft of Wooyoung’s essay in a cross-section peer review exercise, they were understandably skeptical about his methodology. They asked for “a clearer understanding of why analyzing narratives is a credible method to gain insight into this illness.” Wooyoung responded with a revision that provided the theoretical framework necessary to explain the kind of authority those anonymous online posts have in the context of his project. He was wise to listen carefully to his readers. -

Acoustic Biodiversity of Primary Rainforest Ecosystems

Fragments of Extinction: Acoustic Biodiversity of Primary Rainforest Ecosystems David Monacchi a b s t r a c t This paper describes the conceptual origins and develop- ment of the author’s ongoing environmental sound-art project Background Fragments of Extinction, which explores the eco-acoustic com- In 1998, while conducting a field recording campaign on Ital- ity of its organization and making it plexity of the remaining intact ian natural soundscapes, I had the intuition that the biophony available to audiences. In high can- equatorial forests. Crossing [1] of untouched forest ecosystems should exhibit a more opy forests, sounds come from ev- boundaries between bioacous- structured behavior, maximizing efficiency within diversity. I ery direction, including above (e.g. tics, acoustic ecology, electro- acoustic technology and music realized that, if properly reproduced, soundscape recordings birds and monkeys) and below (e.g. composition, the project aims to of these ecosystems could be powerful means for raising aware- amphibians and insects) the listen- reveal the ordered structures of ness of acoustic biodiversity and its heritage [2], now being ing position. The human brain de- nature’s sonic habitats, define a destroyed by rapid deforestation and climate change. When in tects this three-dimensional (3D) possible model of compositional information in its entirety through integration and make the out- 2002, with the help of Greenpeace, I traveled to the equatorial come accessible to audiences Amazon to record in an undisturbed area of old-growth rain- several subparameters that agree to foster awareness of the cur- forest, my hypothesis was immediately confirmed by finding with our composite natural percep- rent “sixth mass extinction.” extremely balanced acoustic systems produced by hundreds tion of direction, depth and dimen- of species of insects, amphibians, birds and mammals neatly sion of sound sources. -

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition

Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition <UN> Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik Die Reihe wurde 1972 gegründet von Gerd Labroisse Herausgegeben von William Collins Donahue Norbert Otto Eke Martha B. Helfer Sven Kramer VOLUME 86 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/abng <UN> Scholarly Editing and German Literature: Revision, Revaluation, Edition Edited by Lydia Jones Bodo Plachta Gaby Pailer Catherine Karen Roy LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> Cover illustration: Korrekturbögen des “Deutschen Wörterbuchs” aus dem Besitz von Wilhelm Grimm; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Wilhelm Grimm’s proofs of the “Deutsches Wörterbuch” [German Dictionary]; Biblioteka Jagiellońska, Libr. impr. c. not. ms. Fol. 34. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jones, Lydia, 1982- editor. | Plachta, Bodo, editor. | Pailer, Gaby, editor. Title: Scholarly editing and German literature : revision, revaluation, edition / edited by Lydia Jones, Bodo Plachta, Gaby Pailer, Catherine Karen Roy. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2015. | Series: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik ; volume 86 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015032933 | ISBN 9789004305441 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: German literature--Criticism, Textual. | Editing--History--20th century. Classification: LCC PT74 .S365 2015 | DDC 808.02/7--dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032933 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0304-6257 isbn 978-90-04-30544-1 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-30547-2 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

18 Au 23 Février

18 au 23 février 2019 Librairie polonaise Centre culturel suisse Paris Goethe-Institut Paris Organisateur : Les Amis du roi des Aulnes www.leroidesaulnes.org Coordination: Katja Petrovic Assistante : Maria Bodmer Lettres d’Europe et d’ailleurs L’écrivain et les bêtes Force est de constater que l’homme et la bête ont en commun un certain nombre de savoir-faire, comme chercher la nourriture et se nourrir, dormir, s’orienter, se reproduire. Comme l’homme, la bête est mue par le désir de survivre, et connaît la finitude. Mais sa présence au monde, non verbale et quasi silencieuse, signifie-t-elle que les bêtes n’ont rien à nous dire ? Que donne à entendre leur présence silencieuse ? Dans le débat contemporain sur la condition de l’animal, son statut dans la société et son comportement, il paraît important d’interroger les littératures européennes sur les représentations des animaux qu’elles transmettent. AR les Amis A des Aulnes du Roi LUNDI 18 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h JEUDI 21 FÉVRIER 2019 à 19 h LA PAROLE DES ÉCRIVAINS FACE LA PLACE DES BÊTES DANS LA AU SILENCE DES BÊTES LITTÉRATURE Table ronde avec Jean-Christophe Table ronde avec Yiğit Bener, Dorothee Bailly, Eva Meijer, Uwe Timm. Elmiger, Virginie Nuyen. Modération : Francesca Isidori Modération : Norbert Czarny Le plus souvent les hommes voient dans la Entre Les Fables de La Fontaine, bête une espèce silencieuse. Mais cela signi- La Méta morphose de Kafka, les loups qui fie-t-il que les bêtes n’ont rien à dire, à nous hantent les polars de Fred Vargas ou encore dire ? Comment s’articule la parole autour les chats nazis qui persécutent les souris chez de ces êtres sans langage ? Comment les Art Spiegelman, les animaux occupent une écrivains parlent-ils des bêtes ? Quelles voix, place importante dans la littérature. -

The History of Emotions Past, Present, Future Historia De Las Emociones: Pasado, Presente Y Futuro a História Das Emoções: Passado, Presente E Futuro

Revista de Estudios Sociales 62 | Octubre 2017 Comunidades emocionales y cambio social The History of Emotions Past, Present, Future Historia de las emociones: pasado, presente y futuro A história das emoções: passado, presente e futuro Rob Boddice Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/939 ISSN: 1900-5180 Publisher Universidad de los Andes Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2017 Number of pages: 10-15 ISSN: 0123-885X Electronic reference Rob Boddice, “The History of Emotions”, Revista de Estudios Sociales [Online], 62 | Octubre 2017, Online since 01 October 2017, connection on 04 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ revestudsoc/939 Los contenidos de la Revista de Estudios Sociales están editados bajo la licencia Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 10 The History of Emotions: Past, Present, Future* Rob Boddice** Received date: May 30, 2017 · Acceptance date: June 10, 2017 · Modification date: June 26, 2017 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.7440/res62.2017.02 Como citar: Boddice, Rob. 2017. “The History of Emotions: Past, Present, Future”. Revista de Estudios Sociales 62: 10-15. https:// dx.doi.org/10.7440/res62.2017.02 ABSTRACT | This article briefly appraises the state of the art in the history of emotions, lookingto its theoretical and methodological underpinnings and some of the notable scholarship in the contemporary field. The predominant focus, however, lies on the future direction of the history of emotions, based on a convergence of the humanities and neuros- ciences, and -

Use of Portable Microbial Samplers for Estimating Inhalation Exposure to Viable Biological Agents

Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology (2007) 17, 31–38 r 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1559-0631/07/$30.00 www.nature.com/jes Use of portable microbial samplers for estimating inhalation exposure to viable biological agents MAOSHENG YAO AND GEDIMINAS MAINELIS Department of Environmental Sciences, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 14 College Farm Road, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901-8551, USA Portable microbial samplers are being increasingly used to determine the presence ofmicrobial agents in the air; however, their performance charac teristics when sampling airborne biological agents are largely unknown. In addition, it is unknown whether these samplers could be used to assess microbial inhalation exposure according to the particle sampling conventions. This research analyzed collection efficiencies of MAS-100, Microflow, SMA MicroPortable, Millipore Air Tester, SAS Super 180, BioCulture, and RCS High Flow portable microbial samplers when sampling six bacterial and fungal species ranging from 0.61 to 3.14mm in aerodynamic diameter. The efficiencies with which airborne microorganisms were deposited on samplers’ collection medium were compared to the particle inhalation and lung deposition convention curves. When sampling fungi, RCS High Flow and SAS Super 180 deposited 80%–90% ofairborne spores on agar F highest among investigated samplers. Other samplers showed collection efficiencies of 10%–60%. When collecting bacteria, RCS High Flow and MAS-100 collected 20%–30%, whereas other samplers collected less than 10% ofthese bioparticles. Comparison ofsamplers’ collection efficiencies with particle inhalation convention curves showed that RCS High Flow and SAS Super 18 0 could be used to assess inhalation exposure to particles larger than 2.5 mm, such as fungal spores. -

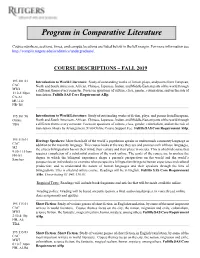

Program in Comparative Literature

Program in Comparative Literature Course numbers, sections, times, and campus locations are listed below in the left margin. For more information see http://complit.rutgers.edu/academics/undergraduate/. COURSE DESCRIPTIONS – FALL 2019 195:101:01 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, CAC North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through MW4 a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of 1:10-2:30pm translation. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. CA-A1 MU-212 HB- B5 195:101:90 Introduction to World Literature: Study of outstanding works of fiction, plays, and poems from European, Online North and South American, African, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Middle-Eastern parts of the world through TBA a different theme every semester. Focus on questions of culture, class, gender, colonialism, and on the role of translation. Hours by Arrangement. $100 Online Course Support Fee. Fulfills SAS Core Requirement AHp. 195:110:01 Heritage Speakers: More than half of the world’s population speaks or understands a minority language in CAC addition to the majority language. This course looks at the way they use and process each of those languages, M2 the effects bilingualism has on their mind, their culture and their place in society. This is a hybrid course that 9:50-11:10am requires completion of a substantial portion of the work online. The goals of the course are to analyze the FH-A1 degree to which the bilingual experience shape a person's perspectives on the world and the world’s Sanchez perspective on individuals; to examine what perspective bilingualism brings to human experience and cultural production; and to understand the nature of human languages and their speakers through the lens of bilingualism. -

Culture and Care Danely, Jason

U20145 CULTURE AND CARE INTRODUCTION This module examines care as one of the most fundamental adaptive strategies for human survival and social flourishing, providing a counterpoint to anthropological accounts that focus on conflict, friction, and violence. The central claim that we will investigate and question over the course is that care has been fundamental to the enhancement of human biosocial evolution and continues to be central as we consider ways to enhance our future. Though fundamental (or because it is fundamental) care has taken on a variety of cultural meanings, structuring social relations from the intimate to the global. Who is deserving of care? When does care of another supersede self-care? Do I have a right to care? Does this right include a right to sex or death? Some of the most important questions about human wellbeing revolve around care. Ethical debates about how to treat socially marginal, non-productive, and vulnerable groups (the sick and disabled, the elderly, children, orphans, immigrants and displaced persons, etc.), for example, depend on deeply invested cultural norms and assumptions surrounding care; if we are to join these debates, we need to be able to critically examine the idea, practice, and felt experience of care. This course begins by examining the evolution of our uniquely human capacity for care, including the neurobiological, emotional, and social adaptations that support empathy and cooperation. Next, we look at moral and ethical dimensions of care as expressed rituals of religious devotion and healing. Third, we look at modern caring institutions and how care has become linked to citizenship, education and welfare. -

Music and Environment: Registering Contemporary Convergences

JOURNAL OF OF RESEARCH ONLINE MusicA JOURNALA JOURNALOF THE MUSIC OF MUSICAUSTRALIA COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA ■ Music and Environment: Registering Contemporary Convergences Introduction H O L L I S T A Y L O R & From the ancient Greek’s harmony of the spheres (Pont 2004) to a first millennium ANDREW HURLEY Babylonian treatise on birdsong (Lambert 1970), from the thirteenth-century round ‘Sumer Is Icumen In’ to Handel’s Water Music (Suites HWV 348–50, 1717), and ■ Faculty of Arts Macquarie University from Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony (No. 6 in F major, Op. 68, 1808) to Randy North Ryde 2109 Newman’s ‘Burn On’ (Newman 1972), musicians of all stripes have long linked ‘music’ New South Wales Australia and ‘environment’. However, this gloss fails to capture the scope of recent activity by musicians and musicologists who are engaging with topics, concepts, and issues [email protected] ■ relating to the environment. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney Despite musicology’s historical preoccupation with autonomy, our register of musico- PO Box 123 Broadway 2007 environmental convergences indicates that the discipline is undergoing a sea change — New South Wales one underpinned in particular by the1980s and early 1990s work of New Musicologists Australia like Joseph Kerman, Susan McClary, Lawrence Kramer, and Philip Bohlman. Their [email protected] challenges to the belief that music is essentially self-referential provoked a shift in the discipline, prompting interdisciplinary partnerships to be struck and methodologies to be rethought. Much initial activity focused on the role that politics, gender, and identity play in music. -

YOKO TAWADA Exhibition Catalogue

VON DER MUTTERSPRACHE ZUR SPRACHMUTTER: YOKO TAWADA’S CREATIVE MULTILINGUALISM AN EXHIBITION ON THE OCCASION OF YOKO TAWADA’S VISIT TO OXFORD AS DAAD WRITER IN RESIDENCE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, TAYLORIAN (VOLTAIRE ROOM) HILARY TERM 2017 ExhiBition Catalogue written By Sheela Mahadevan Edited By Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann and Chantal Wright Contributed to by Yoko Tawada, Henrike Lähnemann, Chantal Wright, Emma HuBer and ChriStoph Held Photo of Yoko Tawada Photographer: Takeshi Furuya Source: Yoko Tawada 1 Yoko Tawada’s Biography: CABINET 1 Yoko Tawada was born in 1960 in Tokyo, Japan. She began to write as a child, and at the age of twelve, she even bound her texts together in the form of a first book. She learnt German and English at secondary school, and subsequently studied Russian literature at Waseda University in 1982. After this, she intended to go to Russia or Poland to study, since she was interested in European literature, especially Russian literature. However, her university grant to study in Poland was withdrawn in 1980 because of political unrest, and instead, she had the opportunity to work in Hamburg at a book trade company. She came to Europe by ship, then by trans-Siberian rail through the Soviet Union, Poland and the DDR, arriving in Berlin. In 1982, she studied German literature at Hamburg University, and thereafter completed her doctoral work on literature at Zurich University. Among various authors, she studied the poetry of Paul Celan, which she had already read in Japanese. Indeed, she comments on his poetry in an essay entitled ‘Paul Celan liest Japanisch’ in her collection of essays named Talisman and also in her essay entitled ‘Die Niemandsrose’ in the collection Sprachpolizei und Spielpolyglotte.