Instructional Outline Smoking the Pipe: Peace Or War?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trends in Bidi and Cigarette Smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by Age, Gender and Education

Research Trends in bidi and cigarette smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by age, gender and education Sujata Mishra,1 Renu Ann Joseph,1 Prakash C Gupta,2 Brendon Pezzack,1 Faujdar Ram,3 Dhirendra N Sinha,4 Rajesh Dikshit,5 Jayadeep Patra,1 Prabhat Jha1 To cite: Mishra S, ABSTRACT et al Key questions Joseph RA, Gupta PC, . Objectives: Smoking of cigarettes or bidis (small, Trends in bidi and cigarette locally manufactured smoked tobacco) in India has smoking in India from 1998 What is already known about this topic? likely changed over the last decade. We sought to to 2015, by age, gender and ▸ India has over 100 million adult smokers, the education. BMJ Global Health document trends in smoking prevalence among second highest number of smokers in the world – 2016;1:e000005. Indians aged 15 69 years between 1998 and 2015. after China. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2015- Design: Comparison of 3 nationally representative ▸ There are already about 1 million adult deaths 000005 surveys representing 99% of India’s population; the per year from smoking. Special Fertility and Mortality Survey (1998), the Sample Registration System Baseline Survey (2004) What are the new findings? and the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (2010). ▸ The age-standardised prevalence of smoking Setting: India. declined modestly among men aged 15–69 years, ▸ Additional material is Participants: About 14 million residents from 2.5 but the absolute number of male smokers at these published online only. To million homes, representative of India. ages grew from 79 million in 1998 to 108 million view please visit the journal in 2015. -

Golden Bat PDF Book

GOLDEN BAT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sandy Fussell,Rhian Nest James | none | 01 May 2011 | Walker Books Australia | 9781921529474 | English | Newtown, Australia Golden Bat PDF Book The packages historically featured a golden bat on a moss green background. Incidentally it was 4 sen 0. Kills in Nyzul Isle will not count toward this trial; it must be defeated in Valkurm Dunes. Electronic cigarettes. Photo Gallery. Looking for something to watch? Antispam by CleanTalk. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. As part of the plans for the exploitation of China, during the thirties and forties the subsidiary tobacco industry of Mitsui had started production of special "Golden Bat" cigarettes using the then popular in the Far East trademark. External Sites. Edit Did You Know? Anime and manga portal. The mastermind of the plan, the General of the Imperial Japanese Army Kenji Doihara was later prosecuted and convicted for war crimes before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East sentenced him to death, but no actions ever took place against the company which profited from their production. After a quick fight, the underwater people kidnap Terry and flee inside a nearby puddle; Gaby tells this to Dr. MediaWiki spam blocked by CleanTalk. Erich Nazo. Company Credits. The design was also changed along with it. User Ratings. The only clip available of "Phantoma Phantaman" on the internet. Start a Wiki. It's worthy to note that the series was actually translated in Spanish as " Fantasmagorico ", with surviving episodes and official VHS releases found around the Internet. Sign In Don't have an account? Emily Paird Andrew Hughes Categories :. -

Trends in Bidi and Cigarette Smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by Age, Gender and Education

Research BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2015-000005 on 6 April 2016. Downloaded from Trends in bidi and cigarette smoking in India from 1998 to 2015, by age, gender and education Sujata Mishra,1 Renu Ann Joseph,1 Prakash C Gupta,2 Brendon Pezzack,1 Faujdar Ram,3 Dhirendra N Sinha,4 Rajesh Dikshit,5 Jayadeep Patra,1 Prabhat Jha1 To cite: Mishra S, ABSTRACT et al Key questions Joseph RA, Gupta PC, . Objectives: Smoking of cigarettes or bidis (small, Trends in bidi and cigarette locally manufactured smoked tobacco) in India has smoking in India from 1998 What is already known about this topic? likely changed over the last decade. We sought to to 2015, by age, gender and ▸ India has over 100 million adult smokers, the education. BMJ Global Health document trends in smoking prevalence among second highest number of smokers in the world – 2016;1:e000005. Indians aged 15 69 years between 1998 and 2015. after China. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2015- Design: Comparison of 3 nationally representative ▸ There are already about 1 million adult deaths 000005 surveys representing 99% of India’s population; the per year from smoking. Special Fertility and Mortality Survey (1998), the Sample Registration System Baseline Survey (2004) What are the new findings? and the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (2010). ▸ The age-standardised prevalence of smoking Setting: India. declined modestly among men aged 15–69 years, ▸ Additional material is Participants: About 14 million residents from 2.5 but the absolute number of male smokers at these published online only. To million homes, representative of India. -

Cultural Affiliation Statement for Buffalo National River

CULTURAL AFFILIATION STATEMENT BUFFALO NATIONAL RIVER, ARKANSAS Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño Nicholas Laluk Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Contract Agreement CA 1248-00-02 Task Agreement J6068050087 UAZ-176 Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85711 June 1, 2008 Table of Contents and Figures Summary of Findings...........................................................................................................2 Chapter One: Study Overview.............................................................................................5 Chapter Two: Cultural History of Buffalo National River ................................................15 Chapter Three: Protohistoric Ethnic Groups......................................................................41 Chapter Four: The Aboriginal Group ................................................................................64 Chapter Five: Emigrant Tribes...........................................................................................93 References Cited ..............................................................................................................109 Selected Annotations .......................................................................................................137 Figure 1. Buffalo National River, Arkansas ........................................................................6 Figure 2. Sixteenth Century Polities and Ethnic Groups (after Sabo 2001) ......................47 -

Tobacco Directory Deletions by Manufacturer

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed From The California Tobacco Directory by Manufacturer Brand Manufacturer Date Comments Removed Catmandu Alternative Brands, Inc. 2/3/2006 Savannah Anderson Tobacco Company, LLC 11/18/2005 Desperado - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Peace - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 Revenge - RYO Bailey Tobacco Corporation 5/4/2007 The Brave Bekenton, S.A. 6/2/2006 Barclay Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Belair Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Private Stock Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/2/2008 2004 Raleigh Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/6/2005 2004 Viceroy Brown & Williamson * Became RJR July 5/3/2010 2004 Coronas Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Palace Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Record Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 VL Canary Islands Cigar Co. 5/5/2006 Freemont Caribbean-American Tobacco Corp. 5/2/2008 Kingsboro Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Roger Carolina Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Aura Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Cheyenne - RYO Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Decade Cheyenne International, LLC 1/5/2018 Bridgeton CLP, Inc. 5/4/2007 DT Tobacco - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Railroad - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Smokers Palace - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Smokers Select - RYO CLP, Inc. 5/30/2008 Southern Harvest - RYO CLP, Inc. 7/13/2007 Davidoff Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 7/19/2016 Malibu Commonwealth Brands, Inc. 5/31/2017 McClintock - RYO Commonwealth Brands, Inc. -

X I.D • for Centuries the Upper Missouri River Valley Was a Lifeline

X Ht:;t 0 ....:J 1\)0 ~ I.D • (1"1' (1"1 For centuries the Upper Missouri River Valley was a lifeline winding patterns. Intermarriage and trade helped cement relations. and through a harsh land, drawing Northern Plains Indians to Its wooded eventually the two cultures became almost Indistinguishable. With banks and rich soli. Earthlodge people, like the nomadic tribes, the Arlkaras to the south, they formed an economic force that hunted bison and other game but were essentially a farming people dominated the region. living In villages along the Missouri and Its tributaries. At the time of their contact with Europeans, these communities were the culmina After contact with Europeans in the early 18th century, the villages tion of 700 years of settlement In the area. Traditional oral histories began to draw a growing number of traders. Tragically. the prosper link the ancestors of the Mandan and Hldatsa tribes living on the Ity that followed was accompanied by an enemy the Indians could Knife River with tribal groups east of the Missouri River. Migrating not fight: European disease. When smallpox ravaged the tribes in for several hundred years along waterways, they eventually settled 1781, the Mandans fled upriver, nearer Hldatsa Village. The people along the Upper Missouri. One Mandan story tells of the group's from Awatlxa Xi'e abandoned their village, returning to the area In creation along the river. Coming Into conflict with other tribes, the 1796 to build Awatixa Village (Sakakawea Site). The weakened Mandans moved northward to the Heart River and adopted an tribes were now easier targets for Sioux raiders, who burned architecture characterized by round earthlodges. -

A Survey on Health Status of Women Beedi Workers in Mukkudal

A SURVEY ON HEALTH STATUS OF WOMEN BEEDI WORKERS IN MUKKUDAL Minor Research Project Report Submitted to MANONMANIAM SUNDARANAR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Prof. B. William Dharma Raja Co-ordinator, PMMMNMTT/MHRD/GOI Professor& Head, School of Education Manonmaniam Sundaranar University Tirunelveli Tamilnadu - 627012. Submitted by Dr.S.Alamelumangai Assistant Professor Centre for Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy Manonmaniam Sundaranar University Abishekapatti, Tirunelveli- 627012. Tamilnadu, India. Page CONTENTS No Foreword by Prof. P. Madhava Soma Sundram i Acknowledgements ii Preface iii List of Tables iv CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION 1-8 CHAPTER –II REVIEW OF LITERATURE 9- 17 CHAPTER – III RESEARCH METHODOL OGY 18-26 27-45 CHAPTER – IV SOCIO- DEMOCRAPHIC CHARATESTIC AND HEALTH STATUS OF WOMEN BEEDI WORKERS 46- 53 CHAPTER – V SUMMARY, FINDINGS, RESULTS AND DISCUSSION CHAPTER – VI CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS 54-56 B1—B4 BIBLIOGRAPHY APPENDIX INTERVIEW SCHEDULE A1- A3 PHOTOS kNdhd;kzpak; Re;judhh; gy;fiyf;fofk; MANONMANIAM SUNDARANAR UNIVERSITY Reaccredited with “A” Grade by NAAC (3rd Cycle) Director, Planning & Development TIRUNELVELI – 627 012. TAMILNADU, INDIA Prof. P. Madhava Soma Sundaram Director, Planning & Development FOREWORD Beedi rolling causes significant health hazards. Beedi rollers are exposed to unburnt tobacco dust through cutaneous and pharyngeal route. The International Labor Organization cites ailments such as exacerbation of tuberculosis, asthma, anemia, giddiness, postural and eye problems, and gynecological difficulties among beedi workers. They are not aware of their rights. Studies have been conducted on beedi workers but not many studies are carried out in rural areas. Thus, any study that is carried out to understand working condition and health hazards in beedi workers residing in the rural areas, adds value to the domain. -

American Indian Views of Smoking: Risk and Protective Factors

Volume 1, Issue 2 (December 2010) http://www.hawaii.edu/sswork/jivsw http://hdl.handle.net/10125/12527 E-ISSN 2151-349X pp. 1-18 ‘This Tobacco Has Always Been Here for Us,’ American Indian Views of Smoking: Risk and Protective Factors Sandra L. Momper Beth Glover Reed University of Michigan University of Michigan Mary Kate Dennis University of Michigan Abstract We utilized eight talking circles to elicit American Indian views of smoking on a U.S. reservation. We report on (1) the historical context of tobacco use among Ojibwe Indians; (2) risk factors that facilitate use: peer/parental smoking, acceptability/ availability of cigarettes; (3) cessation efforts/ inhibiting factors for cessation: smoking while pregnant, smoking to reduce stress , beliefs that cessation leads to debilitating withdrawals; and (4) protective factors that inhibit smoking initiation/ use: negative health effects of smoking, parental and familial smoking behaviors, encouragement from youth to quit smoking, positive health benefits, “cold turkey” quitting, prohibition of smoking in tribal buildings/homes. Smoking is prevalent, but protective behaviors are evident and can assist in designing culturally sensitive prevention, intervention and cessation programs. Key Words American Indians • Native Americans • Indigenous • tobacco • smoking • community based research Acknowledgments We would like to say thank you (Miigwetch) to all tribal members for their willingness to share their stories and work with us, and in particular, the Research Associate and Observer (Chi-Miigwetch). This investigation was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 DA007267 via the University of Michigan Substance Abuse Research Center (UMSARC). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or UMSARC. -

A Comparative Analysis of Early Late Woodland Smoking Pipes from the Arkona Cluster

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-14-2018 1:00 PM Guided by Smoke: A Comparative Analysis of Early Late Woodland Smoking Pipes from the Arkona Cluster Shane McCartney The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Hodgetts, Lisa M. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Anthropology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Shane McCartney 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation McCartney, Shane, "Guided by Smoke: A Comparative Analysis of Early Late Woodland Smoking Pipes from the Arkona Cluster" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5757. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5757 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This thesis undertakes a comparative analysis of ceramic and stone pipes recovered from eight archaeological sites located near present day Arkona, Ontario. Commonly known as the Arkona Cluster, these sites date to between A.D. 1000 and 1280 during the early Late Woodland Period and are thought to be part of a borderland region between distinct cultural groups known as the Western Basin Younge Phase and the Early Ontario Iroquoians. Using a combination of distribution and attribute data from each site’s pipe assemblage, I explore how the similarities and differences observed can be used to draw insights into the potential relations between the sites and how they relate to a larger regional context of identity formation, territorialization and intergroup interaction and exchange. -

WC8810007 Ceremonial Pipe, Probably Iowa, C. 1800-1830. A

WC8810007 Ceremonial Pipe, probably Iowa, c. 1800-1830. A pipe stem made of ashwood, fitting into a red stone pipe bowl, total length 47.75 inches; 121.2 cm. The stem is of the flat type, though slightly convex in cross section, and slightly tapering toward the mouthpiece. From near the mouthpiece down about half of the stem length is wrapped with one quill-plaited bands of porcupine quills. A bundle of horsehair is tied with sinew at the center of the underside, and horsehair also covered the mouthpiece before much of that hair wore off. The pipe bowl is of the elbow type, made of a siliceous argillite called catlinite. The bowl flares up to a banded rim around the slightly rounded top, with a narrow smoke hole. A small ornamental crest rises from the shank. This ceremonial pipe once was in the collection of Andre Nasser; its earlier history is unknown. The formal features of this pipe bowl and its stem indicate their origin from the region between the western Great Lakes and the Missouri River, presumably in the period of c. 1800-1830. An even earlier date might be argued in view of some very similar pipes collected before 1789, now in the Musee de l’Homme, Paris. However, most of the other examples were collected in the early decades of the 19th century. The deep red color and its fairly easy carving made catlinite the favorite pipestone. Contrary to a popular idea, catlinite does not harden on exposure to air. Most of the material was quarried at a well-known site now preserved as Pipestone National Monument, near Pipestone, Minn. -

Plain-Packaging.Pdf

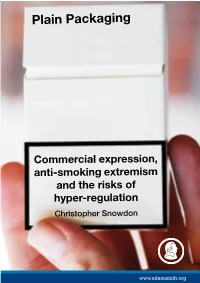

Plain Packaging Commercial expression, anti-smoking extremism and the risks of hyper-regulation Christopher Snowdon www.adamsmith.org Plain Packaging Commercial expression, anti-smoking extremism and the risks of hyper-regulation Christopher Snowdon The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any views held by the publisher or copyright owner. They are published as a contribution to public debate. Copyright © Adam Smith Research Trust 2012 All rights reserved. Published in the UK by ASI (Research) Ltd. ISBN: 1-902737-84-9 Printed in England Contents Executive Summary 5 1 A short history of plain packaging 7 2 Advertising? 11 3 Scraping the barrel 13 4 Will it work? 18 5 Unintended consequences 23 6 Intellectual property 29 7 Who’s next? 31 8 Conclusion 36 Executive summary 1. The UK government is considering the policy of ‘plain packaging’ for tobacco products. If such a law is passed, all cigarettes, cigars and smokeless tobacco will be sold in generic packs without branding or trademarks. All packs will be the same size and colour (to be decided by the government) and the only permitted images will be large graphic warnings, such as photos of tumours and corpses. Consumers will be able to distinguish between products only by the brand name, which will appear in a small, standardised font. 2. As plain packaging has yet to be tried anywhere in the world, there is no solid evidence of its efficacy or unintended consequences. 3. Focus groups and opinion polls have repeatedly shown that the public does not believe that plain packaging will stop people smoking. -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 52 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 52 NO. 1 WINTER 2001 PUBLISHED BY THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio MEMBERSHIP AND DUES TERM Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of EXPIRES A.S.O. OFFICERS January as follows: Regular membership $20.00; husband and wife (one copy of publication) $21.00; Individual Life Membership $400. Husband and wife 2002 President Walt Sperry, 302V? Fairmont Ave., Mt. Vernon, OH Life Membership $600. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published 43050 (740) 392-9774. quarterly, is included in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of 2002 Vice President Russell Strunk, PO Box 55, Batavia, OH Ohio is an incorporated non-profit organization. 45103, (513) 752-7043. PUBLICATIONS AND BACK ISSUES 2002 Immediate Past President Carmel "Bud" Tackett, 905 Charleston Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Pike, Chillicothe, OH 45601, (740) 772-5431. Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $40.00 add $4.50 P-H 2002 Treasurer Gary Kapusta, 3294 Herriff Rd., Ravenna, OH 44266, Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H (330) 296-2287. Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 add $1.50 P-H 2002 Executive Secretary Len Weidner, 13706 Robins Road, The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse.$25.00 add $2.50 P-H Westerville, OH 43081 (740) 965-2868. 1980's & 1990's $ 6.00 add $1.50 P-H 2002 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Drive, Plain City, 1970's $ 8.00 add $1.50 P-H OH 43064, (614)873-5471.