1 Q&A: Medication Restraint Produced by Robert D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2018; 3(1)

ADVANCED JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE. 2019; 3(1): e7 Ziaei et al Review Article DOI: 10.22114/ajem.v0i0.117 Management of Violence and Aggression in Emergency Environment; a Narrative Review of 200 Related Articles Maryam Ziaei1, Ali Massoudifar2, Ali Rajabpour-Sanati3, Ali-Mohammad Pourbagher-Shahri3, Ali Abdolrazaghnejad1* 1. Department of Emergency Medicine, Khatam-Al-Anbia Hospital, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran. 2. Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandarabbas, Iran. 3. Faculty of Medicine, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran. *Corresponding author: Ali Abdolrazaghnejad; Email: [email protected] Published online: 2018-11-29 Abstract Context: The aim of this study is to reviewing various approaches for dealing with agitated patients in emergency department (ED) including of chemical and physical restraint methods. Evidence acquisition: This review was conducted by searching “Violence,” “Aggression,” and “workplace violence” keywords in these databases: PubMed, Scopus, EmBase, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Database, and Google Scholar. In addition to using keywords for finding the papers, the related article capability was used to find more papers. From the found papers, published papers from 2005 to 2018 were chosen to enter the paper pool for further review. Results: Ultimately, 200 papers were used in this paper to conduct a comprehensive review regarding violence management in ED. The results were categorized as prevention, verbal methods, pharmacological interventions and physical restraint. Conclusion: In this study various methods of chemical and physical restraint methods were reviewed so an emergency medicine physician be aware of various available choices in different clinical situations for agitated patients. -

Restraint Module for Travel Nurses

Restraints Objectives Recognize federal regulations related to use of restraint. Distinguish between behavioral and non-behavioral restraint application requirements. Competent to apply restraints Understand proper documentation of restraint use Knowledge of restraint monitoring Knowledge of alternatives to restraint Knowledge of restraint discontinuation 1 Joint Commission and CMS Requirements The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) standards related to restraint use focus on limiting the use of restraints and seclusion to: . Emergency situations when a person is at imminent risk of harming himself or herself or others . When nonphysical safety measures have been ineffective . When safety requires an immediate physical response . Restraint use MUST be Ordered by the Physician AND MUST BE APPROPRIATELY DOCUMENTED Hospital policy on Restraints . The hospital uses restraint or seclusion only when it can be clinically justified or when warranted by patient behavior that threatens the physical safety of the patient, staff, or others . Restraints should be considered once less restrictive interventions have been considered/tried and are determined to be inadequate for the clinical purpose. Any use of restraint will be discontinued at the earliest possible time, based on reassessment of the patient’s continuing need for the restraint . Restraint is never used as a means of coercion, convenience, or retaliation by staff. 2 Definitions RESTRAINTS . A restraint is any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely. A restraint is a drug or medication when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient’s behavior or restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition. -

Florida State Hospital State of Florida Operating Procedure Department of No

FLORIDA STATE HOSPITAL STATE OF FLORIDA OPERATING PROCEDURE DEPARTMENT OF NO. 150-14 CHILDREN AND FAMILIES CHATTAHOOCHEE, April 26, 2017 Health MEDICAL RESTRAINTS & SAFETY DEVICES 1. Purpose: This operating procedure prescribes the use of medical restraints and safety devices at Florida State Hospital. It establishes guidelines and methods to be employed by Hospital staff in restraining residents when the need is of a medical nature. 2. Scope: This procedure applies to all units at Florida State Hospital which use medical restraints. 3. References: a. Florida Statutes, Chapter 394 b. Florida Administrative Code 59A-3, Hospital Licensure c. Restraint Proper Environment OBRA Restraint Guidelines d. State Operations Manual, Appendix A, Survey Protocol, Regulations and Interpretive Guidelines for Hospitals, e. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, HHS. §482.13 Conditions of Participation: Patient’s Rights 4. Philosophy of Florida State Hospital: Medical restraints of residents are methods of last resort and shall not be used unless lesser restrictive methods of intervention have been attempted and determined to be ineffective. Residents will be fully evaluated for restraint elimination and/or reduction at the time of each recovery team review (monthly, bi-monthly, 6-months and annual) and at the time of the 180-day review. Medical restraints shall be applied/ utilized in a manner that is most comfortable to the resident while preserving his/her dignity. Medical Restraints and safety devices shall NOT: a. impair neurovascular integrity; b. impair respiration; c. be tied to bedrails or moving parts of a gerichair or wheelchair; d. prevent residents from eating comfortably; e. interfere with toilet needs; This Operating Procedure supersedes: Operating Procedure 150-14 dated April 21, 2016 OFFICE OF PRIMARY RESPONSIBILITY: Medical Services DISTRIBUTION: See Training Requirements Matrix April26,2017 FSHOP150-14 f. -

Agency Nurse Orientation 2020

CHI Saint Joseph Health: Agency Nurse Orientation 2020 Table of Contents Welcome and Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 4 Mission, Vision and Values .............................................................................................................................. 4 Standards of Conduct ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Orientation Information .................................................................................................................................. 5 CHI Saint Joseph Health Nursing Vision ................................................................................................... 6 Confidentiality .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Disaster Codes .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Dress Code ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Environment of Care ................................................................................................................................ 9 Incident Reporting ................................................................................................................................. -

CMS Restraint Training Requirements H a N D B O O K the CMS Restraint Training Requirements Handbook Is Published by Hcpro, Inc

THE CM Restraint Training Requirements As of January 2007, the Centers for HANDBOOK Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires that your hospital comply with new Conditions of Participation for patient restraint and seclusion. The new requirements focus on patient rights and include additional staff training requirements regarding restraint and seclusion. This portable handbook from HCPro is the perfect training tool to help staff members comply with the new CMS restraint and seclu- sion rules. Concise and easy to use, this handbook explains the specifics of the new training requirements, including the following prescriptive requirements: • Application of restraints • Implementation of seclusion • Monitoring of patients in restraint/seclusion • Assessment of patients in restraint/seclusion • Providing care for a patient in restraint/seclusion It also includes sample competency assessment “skill sheets” for staff who are involved in restraint and seclusion. For additional products about CMS compliance, visit HCPro’s online CMSRT | 200 Hoods Lane | Marblehead, MA | 01945 The CMS Restraint Training Requirements H a n d b o o k The CMS Restraint Training Requirements Handbook is published by HCPro, Inc. Copyright © 2007 HCPro, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. 5 4 3 2 1 ISBN 978-1-60146-068-4 No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without prior written consent of HCPro, Inc., or the Copyright Clearance Center (978/750-8400). Please notify us immediately if you have received an unauthorized copy. HCPro, Inc., provides information resources for the healthcare industry. HCPro, Inc., is not affiliated in any way with The Joint Commission, which owns the JCAHO and Joint Commission trademarks. -

The Lethal Consequences of Restraint

EQUIP FOR EQUALITY A SPECIAL REPORT from the Abuse Investigation Unit NATIONAL REVIEW OF RESTRAINT RELATED DEATHS OF CHILDREN AND ADULTS WITH DISABILITIES: The Lethal Consequences of Restraint UIP FO Q R E E TM Q Y U A L I T UIP FO Q R E E TM Q Y U A L I T Mission Established in 1985, the mission of Equip for Equality is to advance the human and civil rights of people with disabilities in Illinois. Equip for Equality is a private not- for-profit legal advocacy organization designated by the governor to operate the federally mandated Protection and Advocacy System (P&A) to safeguard the rights of people with physical and mental disabilities, including developmental disabilities and mental illness. Equip for Equality is the only comprehensive statewide advocacy organization for people with disabilities and their families. All individuals with a disability in Illinois (as defined by the ADA) are eligible for services, including children, senior citizens, and individuals in state-operated facilities, nursing homes, and community-based programs. Services, Programs, and Projects Abuse Investigation Unit works to prevent abuse, neglect, and deaths of children and adults with disabilities in community-based programs, nursing homes, and state institutions. The Unit works with public investigatory agencies to improve their performance and coordination with each other; conducts investigations of abuse and neglect cases; alerts service providers to dangerous conditions and practices. Public Policy Advocacy achieves changes in state legislation, public policies and programs to safeguard individual rights and personal safety, enhance choice and self- determination, and promote independence, productivity, and community integration. -

Hospital Reporting of Deaths Related to Restraint and Seclusion

Report Template Version = 06-15-05_rev.08 Department of Health and Human Services OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL HOSPITAL REPORTING OF DEATHS RELATED TO RESTRAINT AND SECLUSION Daniel R. Levinson Inspector General September 2006 OEI-09-04-00350 Report Template Version = 06-15-05_rev.08 Office of Inspector General http://oig.hhs.gov The mission of the Office of Inspector General (OIG), as mandated by Public Law 95-452, as amended, is to protect the integrity of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) programs, as well as the health and welfare of beneficiaries served by those programs. This statutory mission is carried out through a nationwide network of audits, investigations, and inspections conducted by the following operating components: Office of Audit Services The Office of Audit Services (OAS) provides all auditing services for HHS, either by conducting audits with its own audit resources or by overseeing audit work done by others. Audits examine the performance of HHS programs and/or its grantees and contractors in carrying out their respective responsibilities and are intended to provide independent assessments of HHS programs and operations. These assessments help reduce waste, abuse, and mismanagement and promote economy and efficiency throughout HHS. Office of Evaluation and Inspections The Office of Evaluation and Inspections (OEI) conducts national evaluations to provide HHS, Congress, and the public with timely, useful, and reliable information on significant issues. Specifically, these evaluations focus on preventing fraud, waste, or abuse and promoting economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in departmental programs. To promote impact, the reports also present practical recommendations for improving program operations. -

6.003 Seclusion Or Restraint Process

OREGON STATE HOSPITAL POLICIES AND PROCEDURES SECTION 6: Patient Care POLICY: 6.003 SUBJECT: Seclusion or Restraint Process POINT CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER PERSON: APPROVED: JOHN SWANSON DATE: NOVEMBER 22, 2017 INTERIM ADMINISTRATOR I. POLICY A. Oregon State Hospital (OSH) provides humane care and treatment to each patient in the least restrictive manner consistent with safety for patients, health care personnel (HCP), and the public. OSH believes that a unit culture and milieu based on respectful, non-coercive interactions between HCP and patients is the safest environment. B. OSH strives to prevent, reduce, and eliminate the use of seclusion or restraint. Seclusion or restraint use is considered an indicator of treatment failure and a safety measure of last resort as expressed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration. C. Non-physical interventions should be used before physical interventions unless safety demands an immediate physical response. HCP must focus on using non- physical interventions early to prevent an emergency situation to decrease the need for using seclusion or restraint. D. The use of seclusion or restraint poses risks to the physical safety and the psychological well-being of the patient and HCP. Therefore, seclusion or restraint may be used only in an emergency when there is imminent danger of harm. 1. The use of restrictive measures must be the result of careful deliberation by HCP who: a. have sufficient clinical knowledge of the patient and the circumstances, and b. who are trained in the theory and practice of seclusion or restraint techniques as well as in the prevention of their use. -

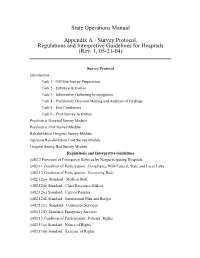

Survey Protocol, Regulations and Interpretive Guidelines for Hospitals (Rev

State Operations Manual Appendix A - Survey Protocol, Regulations and Interpretive Guidelines for Hospitals (Rev. 1, 05-21-04) Survey Protocol Introduction Task 1 - Off-Site Survey Preparation Task 2 - Entrance Activities Task 3 - Information Gathering/Investigation Task 4 - Preliminary Decision Making and Analysis of Findings Task 5 - Exit Conference Task 6 – Post-Survey Activities Psychiatric Hospital Survey Module Psychiatric Unit Survey Module Rehabilitation Hospital Survey Module Inpatient Rehabilitation Unit Survey Module Hospital Swing-Bed Survey Module Regulations and Interpretive Guidelines §482.2 Provision of Emergency Services by Nonparticipating Hospitals §482.11 Condition of Participation: Compliance With Federal, State and Local Laws §482.12 Condition of Participation: Governing Body §482.12(a) Standard: Medical Staff §482.12(b) Standard: Chief Executive Officer §482.12(c) Standard: Care of Patients §482.12(d) Standard: Institutional Plan and Budget §482.12(e) Standard: Contracted Services §482.12(f) Standard: Emergency Services §482.13 Condition of Participation: Patients’ Rights §482.13(a) Standard: Notice of Rights §482.13(b) Standard: Exercise of Rights §482.13(c) Standard: Privacy and Safety §482.13(d) Standard: Confidentiality of Patient Records §482.13(e) Standard: Restraint for Acute Medical and Surgical Care §482.13(f) Standard: Seclusion and Restraint for Behavior Management §482.21 Condition of Participation: Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement §482.21(a) Standard: Program Scope §482.21(b) Standard: -

03-004 Patient Restraint

Wintergreen(Fire(and(Rescue Standard'Operating'Guideline Subject: Patient'Restraint Reference'Number: EMS'030004 Effective'Date: 270Oct014 Last'Revision'Date: 200Feb018 Signature'of'Approval Curtis'Sheets,'Chief Purpose: To provide guidelines on the use of restraints in the field or during transport for patients who are violent or potentially violent and may harm self or others. Policy: 1. When restraints are necessary such activity will be undertaken in a manner that protects the patient's and provider’s health and safety. 2. Behavior restraints are to be used only when necessary in situations where the patient is potentially violent and is exhibiting behavior that is dangerous to self or others. Only reasonable force sufficient to restrain the patient shall be used. 3. Pre-hospital personnel must consider that aggressive or violent behavior may be a symptom of a medical condition such as head trauma, alcohol, drug-related problems, metabolic disorders, stress and psychiatric disorders. The provider must strictly adhere to the TJEMS protocols appropriate for the symptoms presented. 4. The method of restraint used shall allow for adequate monitoring of vital signs and shall not restrict the ability to protect the patient's airway or compromise neurological or vascular status. Definitions: 1. Medical Restraint - is a sub definition of physical restraint and is used to limit the ability or temporarily immobilize a patient for non-behavioral management reasons. (e.g., to promote healing by preventing the dislodgment of medical devices, or to protect a child or adult who is confused and/or disoriented and unable to follow instructions for his/her personal safety). -

HEALTH SERVICES POLICY & PROCEDURE MANUAL North

HEALTH SERVICES POLICY & PROCEDURE MANUAL North Carolina Department Of Public Safety SECTION: Care and Treatment of Prison Patient – Restrictive Procedures POLICY # TX III-3 PAGE 1 of 3 SUBJECT: Use of Restraints for Medical EFFECTIVE DATE: October 2014 Purposes SUPERCEDES DATE: October 2007 References: Related ACA Standards 4th Edition Standards for Adult Correctional Institutions 4-4405 PURPOSE To provide guidelines on the use of physical restraints for medical and/or post-surgical purposes POLICY The offender has the right to be free from any physical or chemical restraints imposed by the medical staff for the purposes of discipline or convenience. Restraints are only to be used when clinically necessary to improve the patient’s well-being and when other less restrictive measures have been found to be ineffective to protect the patient from harm. The restraint should be ended at the earliest possible time based on assessment and reevaluation of the offender’s condition. Only a registered nurse or medical provider has the authority to initiate and discontinue restraints based on clinical judgment. During acute medical and post-surgical care, a restraint may be necessary to ensure that an intravenous or feeding tube will not be removed or when an offender who is temporarily or permanently incapacitated with a broken hip will not attempt to walk before it is medically appropriate. That means a medical restraint may be used to limit mobility or temporarily immobilize a patient related to a medical, post-surgical or dental procedure. The rationale that the offender should be restrained because he/she “might” fall is an inadequate basis for using a restraint. -

Medical Restraints: Bioethical Issues

Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri MEDICAL RESTRAINTS: BIOETHICAL ISSUES 23 April 2015 1 INDEX Presentation ................................................................................................................. 3 1. Premise .................................................................................................................. 4 2. The bioethical scenario……………………………………………………................... 5 3. The normative scenario ......................................................................................... 9 4. Medical restraints in Mental Healthcare and Diagnosis Services: research guidelines ............................................................................................................ 12 5. Restraint and non-restraint culture ....................................................................... 16 6. Reasons for not restraining .................................................................................. 17 7. Strategies of change ............................................................................................ 18 8. Restraints and the elderly .................................................................................... 20 9. The spread of the use of mechanical restraints in residential care facilities and hospitals ....................................................................................................... 21 10. Conclusions and recommendations ..................................................................... 22 2 Presentation The opinion “Medical restraints: