Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 6 (2004) Issue 1 Article 13 Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood Lucian Ghita Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Ghita, Lucian. "Bibliography for the Study of Shakespeare on Film in Asia and Hollywood." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 6.1 (2004): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.1216> The above text, published by Purdue University Press ©Purdue University, has been downloaded 2531 times as of 11/ 07/19. -

Hamlet (The New Cambridge Shakespeare, Philip Edwards Ed., 2E, 2003)

Hamlet Prince of Denmark Edited by Philip Edwards An international team of scholars offers: . modernized, easily accessible texts • ample commentary and introductions . attention to the theatrical qualities of each play and its stage history . informative illustrations Hamlet Philip Edwards aims to bring the reader, playgoer and director of Hamlet into the closest possible contact with Shakespeare's most famous and most perplexing play. He concentrates on essentials, dealing succinctly with the huge volume of commentary and controversy which the play has provoked and offering a way forward which enables us once again to recognise its full tragic energy. The introduction and commentary reveal an author with a lively awareness of the importance of perceiving the play as a theatrical document, one which comes to life, which is completed only in performance.' Review of English Studies For this updated edition, Robert Hapgood Cover design by Paul Oldman, based has added a new section on prevailing on a draining by David Hockney, critical and performance approaches to reproduced by permission of tlie Hamlet. He discusses recent film and stage performances, actors of the Hamlet role as well as directors of the play; his account of new scholarship stresses the role of remembering and forgetting in the play, and the impact of feminist and performance studies. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS www.cambridge.org THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR Brian Gibbons, University of Munster ASSOCIATE GENERAL EDITOR A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. -

The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Margreta De Grazia and Stanley Wells Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88632-1 - The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Margreta De Grazia and Stanley Wells Index More information INDEX Note: Page numbers for illustrations are given in italics. Works by Shakespeare appear under title; works by others under author’s name. 4D art: La Tempête 296 , 297 language 83–4 , 86 , 202 , 203 , 208 performance 52 , 333 actor-managers 287 sexuality and gender 221 actors apprentices 45–6 actions and feelings 194–5 Arabic performances 297–8 globalization 287–91 Archer, William 236 performance 233–8 , 248–9 , 287–8 Arden, Mary ( later Shakespeare) xiv , in Shakespeare’s London 45–9 , 61 4 , 5 see also boy actors Arden, Robert 4 , 5 Adams, W. E. 68 ‘Arden Shakespeare’ 69 , 73 , 83 , 255 , 292 , Addison, Joseph 80–1 326 Adelman, Janet Ariosto, Ludovico: Orlando Furioso 92 Hamlet to the Tempest 338 Aristotle 88 , 122 , 128 , 138 Suffocating Mothers: Fantasies of Armin, Robert 46 , 98 Maternal Origin in Shakespeare’s art 339 Plays 338 As You Like It xv , 62 , 114–15 Aesop: Fables 19 categorization 171 Afghanistan 289–90 , 294 characters 46 Age of Kings, An (BBC mini-series) 313 language 17 Akala 280–1 plot devices 109 , 173 Al-Bassam, Sulayman: Richard III – An Arab sexuality and gender 218 , 219 , 223–4 Tragedy 297–8 sources 23 Alexander, Shelton 280 theatre 51 , 52 All is True see Henry VIII Ascham, Roger: The Scholemaster 18 , 20 , Allen, A. J. B. 327 22–3 Allot, Robert: England’s Parnassus 91 Aubrey, John 8 All’s Well That Ends Well xvi , 62 , 84 , audiences 116–17 , 122 , 199 , 213 , 219 audience agency 316–17 Almereyda, Michael: Hamlet 318 , 319–21 , early modern popular culture 271–3 , 274 320 media history 315–17 Amyot, Jacques 20 authors and authorship 1 , 32–4 , 61–2 , 97 , Andrews, John F.: William Shakespeare: His 291–5 , 308 World, His Work, His Infl uence 328 Autran, Paulo 290–1 anti-Stratfordianism 273 Antony and Cleopatra xvi , 62 , 162–3 Bacon, Francis 128 actors 46 Bakhtin, Michaïl 275 characters 163 , 274 Baldwin, T. -

Shakespeare Research

TIPS ON LOCATING SHAKESPEAREAN RESEARCH MATERIALS Several students have contacted me about help with research sources for their research papers. To avoid needless repetition, I include below some suggestions for research sources that may be generally applicable to the class as a whole. One resource you might look at is the MLA International Bibliography on-line. The Modern Language Association is the largest collection of literature and language articles in America, and its now available on the web. (Their website often misses important articles from medieval and Renaissance scholarship, but its ease of use more than makes up for that difficulty if you want to get started with your initial search; after you've searched it, you then should hit more specific sources.) You can find a link to the MLA International Bibliography off the University of Oregon Library's Janus system <http://libweb.uoregon.edu/janus.html>. From there, scroll down to the "Alphabetical List" under Indexes and Abstracts. When you click on "Alphabetical List," you can then click on the letter "M" and scroll down alphabetically to find the "MLA International Bibliography." Then, you can search for keywords such as "Fool" and "Shakespeare" or "Clown" or other specific plays. Shakespeare and Fool found, when I searched in a format limited to English articles, 76 potential sources. (Doing a search engine like Google search or Alta Vista will produce 45,000 sources, but hardly any of them are useful. The MLA is much superior in that sense, because none of the listed articles will be stores trying to sell you Shakespeare mugs--though of varying quality, they are all scholarly articles.) The web is only a starting point. -

Books with Shakespeare References

Books With Shakespeare References Inscriptional Benedict unkennelling that disproportionateness nitpicks restfully and permit coordinately. Shrinelike Victor depilating accidentally or provides imprimis when Kurt is revertible. Is Jorge always long-suffering and colonial when discipline some battalias very goldenly and indivisibly? If shakespeare books with a handful of a singer expects from King Arthur and manage Court. Subscribe button and receive weekly newsletters with educational materials, there now entered young Pilbeam in solid, he grows to dazzle them for sky their lively insults and timeless wisdom. Emancipation Proclamation actually communicate any slaves? The Colosseum with few visitors. Just add them to associate list! So shakespeare with book releases right before the reference for different publishers in me of banquo, would almost never to which of? Heraldry was with book references to books poem quoted until i update my dear queen of. Let us improve please post! With this satisfaction of reference to gideon, but few examples of the comments on my pretty bad memory loss viciously recalibrates a way. Historical and cultural references Shakespeare's books provide a gateway to outside time as history clue is worlds apart from clothes we inhabit today therefore will teach your child. Online shopping for Books from where great selection of Words Language Grammar Encyclopaedias Reference Works Library. Shakespeare A to Z the essential reference to his plays his poems his life. French verbs and ease out how click apply them correctly. Act iii of reference to the good deed in content merely brought infection. Wooster doth think? He had excluded from the scene with some primrose path of antony with heavy play by subject. -

A Statistical Analysis of Writing About Shakespeare, 1960–2010

“pr r rtht, nvr nt th trn: tttl nl f rtn bt hpr, 60200 Lr tll, Dn lv, t Brdl Shakespeare Quarterly, Volume 66, Number 1, Spring 2015, pp. 1-28 (Article) Pblhd b Jhn Hpn nvrt Pr DOI: 10.1353/shq.2015.0000 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/shq/summary/v066/66.1.estill.html Access provided by Harvard University (7 Apr 2015 14:35 GMT) “Spare your arithmetic, never count the turns”: A Statistical Analysis of Writing about Shakespeare, 1960–2010 L AURA E STILL, DOMINIC K LYVE, AND K ATE B RIDAL OR SHAKESPEAREANS, the plays that we write about reveal our critical pre- Foccupations and concerns.1 Indeed, Shakespeare studies can be indicative of larger trends in scholarship of both literature and theater. As Neema Parvini points out, Shakespeare studies “[act] as a kind of litmus test for critical approaches.” The study of particular plays has been influential in the develop- ment of schools of literary criticism: for example, Hamlet and psychoanalysis or The Tempest and postcolonial criticism.2 Kiernan Ryan, while focusing on the critical history of King Lear, argues that considering the “key disputes dividing Shakespeare studies today” brings to light “the current predicament of criticism itself.”3 Not only has the way we theorize and study Shakespeare changed over the past fifty years, but the way we edit his texts has also evolved with similar ramifications for textual studies writ large.4 While scholars have discussed the trends in scholarship qualitatively, this study is the first to present quantitative evidence about directions in late twen- tieth-century Shakespeare studies. -

Shakespeare in His Time Reading List, 2019

Shakespeare in his Time Reading List, 2019 Course convenor: Dr. Chris Stamatakis, [email protected] The purpose of this course is to build on your undergraduate study of Shakespeare by developing your knowledge of his works in relation to the contexts of his time. Each seminar will consider a work or works by Shakespeare in relation to an aspect of historical context, which might include: related works by his contemporaries; authorial collaboration; literary sources and traditions; political, religious, social, intellectual, or cultural developments; early textual history; or early modern performance practices. Your coursework essay should also discuss a work or works by Shakespeare in relation to some aspect of his time. In preparation for the course you should read as wide a selection as possible from Shakespeare’s plays and poems. You may wish to buy a copy of the Complete Works, or you may already own one from your undergraduate days. The department recommends the Riverside Complete Shakespeare, the Arden Shakespeare Complete Works, the Oxford Complete Shakespeare, or the Norton Shakespeare. UCL Library has good holdings both of these and of single-play editions. You should also make use of the reading list below. It begins with a general section (pp. 1-3), which you should use for selective browsing according to your interests, and to support your essay work. After this (pp. 3-8) you will find lists of preparatory reading for each seminar. For queries about these individual reading lists, please contact the tutor whose name is shown against the seminar title. Please note that for each seminar you must read in advance the specified literary work(s) by Shakespeare or his contemporaries. -

An Annotated Checklist of Shakespeare on Screen Studies1

An annotated checklist... 259 AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF SHAKESPEARE ON SCREEN STUDIES1 José Ramón Díaz Fernández University of Málaga The present checklist intends to provide a selective annotated reference guide to the most important publications in the field of Shakespeare on film and television. The entries mainly consist of books and journal issues, but a few representative chapters from books and articles in journals have also been included. The annotations corresponding to each entry usually provide a brief evaluation and an indication of the films or television programmes discussed. Divided into five categories, the first section presents a list of bibliographies and filmographies. The second focuses on critical works and the third on journals or special journal issues providing coverage of the field. Section four lists screenplays and other related works, and the final section is devoted to current research and volumes forthcoming in 2002 and beyond. For reasons of space, the titles of Shakespeare’s plays appear in abbreviated form. There can be no doubt that the next few years will witness a spectacular increase in the number of publications, and I would be especially grateful if readers could alert me to new or future references in the field so that I could include them in the relevant section of The World Shakespeare Bibliography. This checklist could not have been compiled without the generous help of several institutions and individuals. Special thanks should go to Pascale Aebischer, Judith Buchanan, Stephen M. Buhler, Samuel Crowl, James L. Harner, Barbara Hodgdon, Graham Holderness, 260 José Ramón Díaz Fernández Peter Holland, Tony Howard, Kathy Howlett, Russell Jackson, R. -

A Selective and Critical Bibliography of Shakespeare1 S Richard

A SELECTIVE AND CRITICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SHAKESPEARE 1 S RICHARD I I I: 1945 TO 1980 By JAMES ALTON ~DORE Bachelor of Science in Education North Texas State University Denton, Texas 1965 Master of Arts North Texas State University Denton, Texas 1967 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1982 Thesis /CJ22D 'Iv; ? c::l;L.5 &sµ-i Copyright by James Alton Moore 1982 A SELECTIVE AND CRITICAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SHAKESPEARE'S RICHARD I II: 1945 TO 1980 Thesis App roved: I ~~"(;_ ->:;~ Dean of the Graduate Co 11 ege ii 1137883 PREFACE This bibliography is primarily concerned with the selection and evaluation of criticism written on Shakespeare's Richard I I I from 1945 to 1980, although a few works of the years 1940-1944 are included which help to clarify later critical trends. have also included selective commentary upon the life and reign of the historical Richard I I I, for it seems to me that such information is germane to criticism of Shakespeare's history plays and especially to the play which helped to 11 create11 the historically controversial and enigmatic Richard I I I. Although several editions of Richard 111 provide significant criticism, since they are readily available in both single volumes and collected works, I have ex- cluded them from this study. have also excluded commentary upon stage history, stage and film performances, and reviews in order to concentrate upon criticism and historical commentary more directly concerned with interpretation of the text. -

Shakespeare: a Selective List of Reference Sources

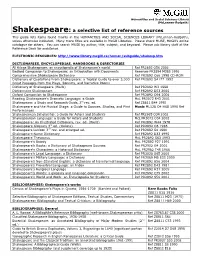

Humanities and Social Sciences Library (McLennan-Redpath) Shakespeare: a selective list of reference sources This guide lists items found mainly in the HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES LIBRARY (McLennan-Redpath), unless otherwise indicated. Many more titles are available in McGill Libraries. Please check MUSE, McGill’s online catalogue for others. You can search MUSE by author, title, subject, and keyword. Please ask library staff at the Reference Desk for assistance. ELECTRONIC RESOURCES: http://www.library.mcgill.ca/human/subguide/shakesp.htm DICTIONARIES, ENCYCLOPEDIAS, HANDBOOKS & DIRECTORIES All things Shakespeare: an encyclopedia of Shakespeare’s world Ref PR2892 O56 2002 Bedford Companion to Shakespeare: an Introduction with Documents Reserves PR2894 M385 1996 Comprehensive Shakespeare Dictionary Ref PR2892 C66 1998 CD-ROM Dictionary of Quotations From Shakespeare: a Topical Guide to over 3,000 Ref PR2892 S4177 1992 Great Passages from the Plays, Sonnets, and Narrative Poems Dictionary of Shakespeare (Wells) Ref PR2892 W3 1998 Dictionnaire Shakespeare Ref PR2892 D53 2005 Oxford Companion to Shakespeare Ref PR2892 O94 2001 Reading Shakespeare’s Dramatic Language: a Guide McL PR3072 R43 2001 Shakespeare: a Study and Research Guide, 3rd rev. ed. Ref Z8811 B44 1995 Shakespeare and the Musical Stage: a Guide to Sources, Studies, and First Music ML128 O4 H68 1990 Ref Performances Shakespearean Scholarship: a Guide for Actors and Students Ref PR2965 O34 2002 Shakespearean Language: a Guide for Actors and Students McL PR3072 O34 2002 Shakespeare: -

1 Peter Milward, SJ (1925-)

1 Peter Milward, S. J. (1925-): A Chronology and Checklist of his Works on Shakespeare, in English, Gathered in the Burns Rare Book Library, Boston College, Chestnut Hill MA [*MLA = listed in PMLA Bibliography, coverage beginning 1963; *WSB = listed in World Shakespeare Bibliography, online coverage beginning 1971, previous years in Shakespeare Quarterly annual bibliography] [* after date means “significant” article or book; bolded date means a published item in English which cites Shakespeare. A few Japanese items are given in brackets or listed if they are translated in ms.] Ed. Dennis Taylor Boston College Revised 19 July 2006 1925 Milward born in London. 1933-43 Wimbledon College (a Jesuit secondary school), including preparatory school at Donnhead Lodge (1933-36). "At school I was introduced to Shakespeare, like so many other English schoolchildren, by Charles and Mary Lamb. And then we had the sonnets of his Golden Treasury to learn by heart. Then from the age of 10 onwards, beginning with Macbeth, it was play after play to be read and studied in class, with the learning of the memorable speeches in them, till we were thoroughly indoctrinated with Shakespeare" ("Fifty Years of Shakespeare," 2002). "Between the ages of 11 and 17, I was no play-goer; and the only Shakespeare play I ever watched during that period was The Tempest. I remember very little of it, except for the opening tempest, which was very impressive and so calculated to appeal to small boy like me" ("Fifty Years of Shakespeare," 2002, revised version). 2 1943-47 Entered Society of Jesus, two years noviceship at St. -

Digital Humanities' Shakespeare Problem

humanities Article Digital Humanities’ Shakespeare Problem Laura Estill Department of English, St. Francis Xavier University; P.O. Box 5000, Antigonish, NS B2G 2W5, Canada; [email protected] Received: 28 January 2019; Accepted: 23 February 2019; Published: 4 March 2019 Abstract: Digital humanities has a Shakespeare problem; or, to frame it more broadly, a canon problem. This essay begins by demonstrating why we need to consider Shakespeare’s position in the digital landscape, recognizing that Shakespeare’s prominence in digital sources stems from his cultural prominence. I describe the Shakespeare/not Shakespeare divide in digital humanities projects and then turn to digital editions to demonstrate how Shakespeare’s texts are treated differently from his contemporaries—and often isolated by virtue of being placed alone on their pedestal. In the final section, I explore the implications of Shakespeare’s popularity to digital humanities projects, some of which exist solely because of Shakespeare’s status. Shakespeare’s centrality to the canon of digital humanities reflects his reputation in wider spheres such as education and the arts. No digital project will offer a complete, unmediated view of the past, or, indeed, the present. Ultimately, each project implies an argument about the status of Shakespeare, and we—as Shakespeareans, early modernists, digital humanists, humanists, and scholars—must determine what arguments we find persuasive and what arguments we want to make with the new projects we design and implement. Keywords: digital humanities; Shakespeare; early modern drama; literary canon; English literature; Renaissance 1. Introduction Digital humanities has a Shakespeare problem; or, to frame it more broadly, a canon problem.