Education and Koranic Literacy in West Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Question of 'Race' in the Pre-Colonial Southern Sahara

The Question of ‘Race’ in the Pre-colonial Southern Sahara BRUCE S. HALL One of the principle issues that divide people in the southern margins of the Sahara Desert is the issue of ‘race.’ Each of the countries that share this region, from Mauritania to Sudan, has experienced civil violence with racial overtones since achieving independence from colonial rule in the 1950s and 1960s. Today’s crisis in Western Sudan is only the latest example. However, very little academic attention has been paid to the issue of ‘race’ in the region, in large part because southern Saharan racial discourses do not correspond directly to the idea of ‘race’ in the West. For the outsider, local racial distinctions are often difficult to discern because somatic difference is not the only, and certainly not the most important, basis for racial identities. In this article, I focus on the development of pre-colonial ideas about ‘race’ in the Hodh, Azawad, and Niger Bend, which today are in Northern Mali and Western Mauritania. The article examines the evolving relationship between North and West Africans along this Sahelian borderland using the writings of Arab travellers, local chroniclers, as well as several specific documents that address the issue of the legitimacy of enslavement of different West African groups. Using primarily the Arabic writings of the Kunta, a politically ascendant Arab group in the area, the paper explores the extent to which discourses of ‘race’ served growing nomadic power. My argument is that during the nineteenth century, honorable lineages and genealogies came to play an increasingly important role as ideological buttresses to struggles for power amongst nomadic groups and in legitimising domination over sedentary communities. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850

The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Benjamin, Jody A. 2016. The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493374 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 A dissertation presented by Jody A. Benjamin to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African and African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2016 © 2016 Jody A. Benjamin All rights reserved. Dissertation Adviser: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Jody A. Benjamin The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 Abstract This study re-examines historical change in western Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the lens of cotton textiles; that is by focusing on the production, exchange and consumption of cotton cloth, including the evolution of clothing practices, through which the region interacted with other parts of the world. It advances a recent scholarly emphasis to re-assert the centrality of African societies to the history of the early modern trade diasporas that shaped developments around the Atlantic Ocean. -

El León Y El Cazador. História De África Subsahariana Titulo Gentili, Anna Maria

El león y el cazador. História de África Subsahariana Titulo Gentili, Anna Maria - Autor/a Autor(es) Buenos Aires Lugar CLACSO Editorial/Editor 2012 Fecha Colección Sur-Sur Colección Independencia; Descolonización; Colonialismo; Estado; Historia; Etnicidad; Mercado; Temas África; Libro Tipo de documento http://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/clacso/sur-sur/20120425121712/ElLeonyElCazado URL r.pdf Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.0 Genérica Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar EL LEÓN Y EL CAZADOR A Giorgio Mizzau Gentili, Anna Maria El león y el cazador : historia del África Subsahariana . - 1a ed. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : CLACSO, 2012. 576 p. ; 23x16 cm. - (Programa Sur-Sur) ISBN 978-987-1543-92-2 1. Historia de África. I. Título CDD 967 Otros descriptores asignados por la Biblioteca Virtual de CLACSO: Historia / Estado / Colonialismo / Descolonización / Independencia / Etnicidad / Mercado / Democracia / Tradición / África subsahariana Colección Sur-Sur EL LEÓN Y EL CAZADOR HISTORIA DEL ÁFRICA SUBSAHARIANA Anna Maria Gentili Editor Responsable Emir Sader - Secretario Ejecutivo de CLACSO Coordinador Académico Pablo Gentili - Secretario Ejecutivo Adjunto de CLACSO Área de Relaciones Internacionales Coordinadora Carolina Mera Asistentes del Programa María Victoria Mutti y María Dolores Acuña Área de Producción Editorial y Contenidos Web de CLACSO Responsable Editorial Lucas Sablich Director de Arte Marcelo Giardino Producción Fluxus Estudio Impresión Gráfica Laf SRL Primera edición El león y el cazador. -

Introduction

Introduction This book aims to study the lives of a number of West African ʿulamāʾ from northern Nigeria, Mali, and Mauritania, who, after seeing the defeat of the Muslim jihād against European colonizers, chose to undertake the hijra (emi- gration) to Mecca and Medina. In doing so they seized the opportunity to perform the ḥajj (pilgrimage to Mecca), and later settled there as mujāwirūn/ mujāwir (residents of the neighborhoods of the two holy mosques of Mecca and Medina). In this hijra, the majority of people took the Sudan route (rather than the Maghrib route to Cairo and then to the Hijaz), which in the nine- teenth- and early twentieth-century was the more common route of most West African pilgrims to Mecca and Medina. Some of these pilgrims who were fleeing colonization were also, to a lesser extent, attracted by opportunities to work in agriculture (especially cotton cul- tivation) or in the army in Sudan, first under the rule of the Mahdī and then under English colonial rule. The descendents of these migrants now form a significant proportion of the population in Sudan, where they are often called Fallāta; in Saudi Arabia they are called Takārira or Takkāra (sing. Takrūrī).1 Some of these West African ʿulamāʾ who arrived in the Hijaz after the conquest of the region by Ibn Saʿūd (1925–26) embraced his Wahhābī-Salafī doctrine and helped spread it through the Hijaz and elsewhere in Saudi Arabia by teaching and preaching in mosques and schools. In this book, I argue that these ʿulamāʾ from Africa (and also those from India) in Mecca and Medina were not working for an international Islamic project, but were rather performing the Islamic duty of daʿwa (missionary work or propaganda), which for them was to spread the Wahhābiyya—the version of Islam they came to embrace and that they regarded as the only correct and valid doctrine. -

A Tale of Two Floodplains: Comparative Perspectives on the Emergence of Complex Societies and Urbanism in the Middle Niger and Senegal Valleys

A tale of two floodplains: comparative perspectives on the emergence of complex societies and urbanism in the middle Niger and Senegal valleys SUSAN KEECH MCINTOSH Floodplains have always had a special place in the study of human social complexity. Particularly in the case of floodplains in otherwise arid regions, the consequences for human society of access by agriculturalists to a vital, localized resource – water – are revealing by their contrast with surrounding areas. For many reasons, among them the discipline’s long- standing preoccupation with pristine cultural developments, no studies were undertaken prior to the late 1970’s of arid-region floodplains in sub-Saharan Africa. The widespread assumption was that cultural complexity in sub-Saharan Africa as a whole was late, and derived, regardless of its geographic situation. The purpose of this paper is to outline the archaeological sequences that have emerged as the result of fieldwork by my husband, myself and others1 in the two great floodplains of the west African Sahel, the inland Niger delta of Mali and the middle Senegal valley of Senegal. I will show how the sequences revealed by archaeology are dramatically different in the two floodplains, involving precocious site growth and population aggregation during the first millennium AD in the case of the inland Niger delta, and a very decentralized, non-agglomerated population distribution during the same time period in the case of the middle Senegal valley. I will discuss the various aspects of the two floodplains that encouraged these differences and then close with some brief comments on the relevance of these findings to comparative studies of cultural complexity and urbanism. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Dick's Creek and Its Southerly Tributary That Parallels Oakdale and Merritt Street for About 2.5 Kilometers

Dick’s Creek Richard Pierpoint “Captain Dick” Courageous Leader, Soldier, Hero To the West of Merritt Street, St.Catharines running along side present day Oakdale Avenue within Canal Valley, is Dick’s Creek. Its waterway tells a discordant series of tales that informs that which we see today on Merritt Street. The first and second Welland canals followed Dick’s Creek as they left the boundary of St. Catharines (as it was in 1829 to 1915) and travelled south toward the town of Merritton and the Niagara Escarpment. The First Welland Canal finished in 1829 and used for fifteen years, and the Second Welland Canal finished in 1845 and used until 1915 both follow the main branch of Dick's Creek and its southerly tributary that parallels Oakdale and Merritt Street for about 2.5 kilometers. Dick’s Creek was named after respected, well-liked, Richard “Captain Dick” Pierpoint, who in his life- time was captured by or sold by local slave traders to an America bound British slave ship at 16, escaped American slavery by joining the Loyalist militia in 1780 at 36, acquired in recognition of his brave service a large land grant in 1791 encompassing Dick’s Creek at 47, voluntarily fought in the war of 1812 on behalf of Upper Canada against the Americans as a member of the Coloured Militia he co-founded at 68, received and fulfilled the harsh conditions of acquiring a further land grant in Fergus at the age of 82, and then returned to the area of Dick’s Creek now actively used as part of the Welland Canal where he lived nobly until his death in 1838 at the distinguished age of 94. -

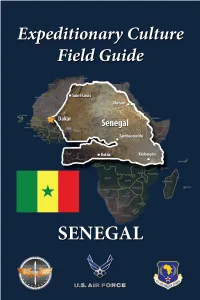

ECFG-Senegal-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo a courtesy of the United Nations). The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” ECFG the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Senegal, focusing on unique cultural Senegal features of Senegalese society and is designed to complement other pre- deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Syed Dissertation Final 2

Al-ḤājjʿUmar Tāl and the Realm of the Written: Mastery, Mobility and Islamic Authority in 19th Century West Africa by Amir Syed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolph T. Ware, Chair Professor Paul Johnson Professor Rüdiger Seesemann, University of Bayreuth Professor Andrew Shryock Dedication To my parents, Safiulla and Fazalunissa, for bringing me here; And to Shafia, Neha, and Lina, for continuing to enrich me ii Acknowledgements It is overwhelming to think about the numerous people who made this journey possible; from small measures of kindness, generosity and assistance, to critical engagement with my ideas, and guiding my intellectual development. Words cannot capture the immense gratidue that I feel, but I will try. I would never have become a historian without the fine instruction I received from the professors at the University of British Columbia. From among them, I will single out Paul Lewin Krause, whose encouragement and support first put me on this path to scholarship. His lessons on writing and teaching are a treasure trove that, so many years later, I continue to draw from. By coming to the University of Michigan, I found a new set of professors, colleagues, and friends. Through travel and intellectual engagement, away from Ann Arbor, I also met many others who have helped me over the years. I would like to first thank my committee members for helping me see this project through. Over numerous years, and perhaps hundreds of conversations, my advisor, Butch Ware, helped me develop my ideas, and get them onto paper. -

Muslim Identity in the Archaeological Record of American Enslavement Kacie Allen

African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter Volume 12 Article 2 Issue 3 September 2009 9-1-2009 Looking East: Muslim Identity in the Archaeological Record of American Enslavement Kacie Allen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/adan Recommended Citation Allen, Kacie (2009) "Looking East: Muslim Identity in the Archaeological Record of American Enslavement," African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/adan/vol12/iss3/2 This Articles, Essays, and Reports is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Allen: Looking East: Muslim Identity in the Archaeological Record of Ame September 2009 Newsletter Looking East: Muslim Identity in the Archaeological Record of American Enslavement B y Kacie Allen* Abstract A significant number of those Africans enslaved in the Americas were Muslim. Archaeological investigation has yet to be made concerning their stories. This article explores the archaeology of Islam to provide a foundation for understanding the materiality of Muslim identity as it appears in the context of American enslavement, and the historical circumstances which resulted in significant numbers of African Muslims becoming enslaved in the Americas. Drawing on the documentary record, it relates a selection of the life stories of enslaved African American Muslims. In pursuit of a critical, explanatory, and emancipatory archaeology, I undertake an examination of artifacts recovered from contexts of African and African American enslavement in North America. -

Cronología De Las Guerras En La Baja Edad Media: Europa Y Resto Del Mundo

CRONOLOGÍA DE LAS GUERRAS EN LA BAJA EDAD MEDIA: EUROPA Y RESTO DEL MUNDO Magatem, 16 de noviembre del 2018 Susana Noemí Tomasi En la tabla siguiente se determinan las guerras (ya sean entre países, zonas geográficas, reinos, ciudades o guerras civiles dentro de un mismo país o reino) cronológicamente, que se encuentran registradas en la Baja Edad Media y que han sido desarrolladas en los Tomo III y IV de “LA RELACIÓN ENTRE LAS CRISIS ECONOMICAS Y LAS GUERRAS – EN LA EDAD MEDIA- SEGUNDA PARTE BAJA EDAD MEDIA – EUROPA Y RESTO DEL MUNDO”. FECHA LUGAR DESCRIPCION DEL ACTO DE GUERRA 985/1014 India Rajaraja Chola, derrotó a los Chalukyas del este, los Pandyas de Madurai y las Gangas de Mysore. 985/1014 India En la guerra contra los Pandyas, Rajaraja capturó al rey de Pandya, Amarabhujanga y a los generales Cholas, en el puerto de Virinam. 985/1014 India Durante el reinado de Rajaraja Chola, hubo continuas guerras con los Chalukyas occidentales para afirmar la supremacía 988/991 Francia Guerra civil entre Carlos, duque de Lorena, apoyado por el duque de Aquitania, Guillermo IV, contra Hugo Capeto, duque de Francia, quien triunfó y reinó hasta 996. 993 Ghazni El emir Nuh II ibn Manṣūr se enfrentó a la rebelión de sus jefes Fa'iq y 'Abu ‘Alī Simjuri y pidió ayuda a Sevuk Tegin que intervino en Jorasán para equilibrar fuerzas. 994 Japón Hubo levantamientos en diferentes provincias y el emperador envió a comandantes de las tropas imperiales, para detener los mismos. 994 Europa El emperador de los búlgaros Samuel, atacó Croacia, Central venciendo al Zupan Vladimir y marchando hacia Zadar, donde sitió al rey en la ciudad de Nin, sin tomarla regresó a Bulgaria.