Jewish Women 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting Your Get At

Getting your Get at www.gettingyourget.co.uk Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers. by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB The website at www.gettingyourget.co.uk is sponsored by Barnett Alexander Conway Ingram, Solicitors, London 1 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Dedicated to the loving memory of Sharon Faith’s late parents, Maisie and Dr Oswald Ross (zl) and Deanna Levine’s late parents, Cissy and Ellis Levine (zl) * * * * * * * * Published by Cissanell Publications PO Box 12811 London N20 8WB United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 © Sharon Faith and Deanna Levine First edition: February 2002 Second edition: July 2002 Third edition: 2003 Fourth edition: 2005 ISBN 0-9539213-1-X Fifth edition: 2006 ISBN 0-9539213-4-4 Sixth edition: 2008 ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 2 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Getting your Get Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB List of Contents Page Number Letters of endorsement. Quotes from letters of endorsement ……………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgements. Family Law in England, Wales and Scotland. A note for the reader seeking divorce…………. 8 A note for the lawyer …………….…….. …………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 Legislation: England and Wales …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 Legislation: Scotland ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 1. Who needs a Get? .……………………………………………………………………………….…………………... 14 2. What is a Get? ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 3. Highlighting the difficulties ……………………………………………………………………………….………….. 15 4. Taking advice from your lawyer and others ………………………………………………………………………. -

A QUARTERLY of WOMEN's STUDIES RESOURCES WOMEN's STUDIES LIBRARIAN University of Wisconsin System

WOMEN’S STUDIES LIBRARIAN FEMINIST COLLECTIONS A QUARTERLY OF WOMEN’S STUDIES RESOURCES Volume 33 Number 1 Winter 2012 University of Wisconsin System Feminist Collections A Quarterly of Women’s Studies Resources Women’s Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library 728 State St. Madison, WI 53706 Phone: 608-263-5754 Fax: 608-265-2754 Email: [email protected] Website: http://womenst.library.wisc.edu Editors: Phyllis Holman Weisbard, JoAnne Lehman Cover drawing: Miriam Greenwald Drawings, pp. 15, 16, 17: Miriam Greenwald Graphic design assistance: Daniel Joe Staff assistance: Linda Fain, Beth Huang, Michelle Preston, Heather Shimon, Kelsey Wallner Subscriptions: Wisconsin subscriptions: $10.00 (individuals affiliated with the UW System), $20.00 (organizations affili- ated with the UW System), $20.00 (individuals or non-profit women’s programs), $30.00 (institutions). Out-of-state sub- scriptions: $35.00 (individuals & women’s programs in the U.S.), $65.00 (institutions in the U.S.), $50.00 (individuals & women's programs in Canada/Mexico), $80.00 (institutions in Canada/Mexico), $55.00 (individuals & women's programs elsewhere outside the U.S.), $85.00 (institutions elsewhere outside the U.S.) Subscriptions include Feminist Collections, Feminist Periodicals, and New Books on Women, Gender, & Feminism. Wisconsin subscriber amounts include state tax (except UW organizations amount). All subscription rates include postage. Feminist Collections is indexed by Alternative Press Index, Women’s Studies International, and Library, Information Science, & Technology Abstracts. It is available in full text in Contemporary Women’s Issues and in Genderwatch. All back issues of Feminist Collections, beginning with Volume 1, Number 1 (February 1980), are archived in full text in the Minds@UW institutional repository: http://minds.wisconsin.edu/handle/1793/254. -

Wertheimer, Editor Imagining the Seth Farber an American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B

Imagining the American Jewish Community Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor For a complete list of books in the series, visit www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSAJ.html Jack Wertheimer, editor Imagining the Seth Farber An American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Murray Zimiles Gilded Lions and Soloveitchik and Boston’s Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to Maimonides School the Carousel Ava F. Kahn and Marc Dollinger, Marianne R. Sanua Be of Good editors California Jews Courage: The American Jewish Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe “How Committee, 1945–2006 Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Hollace Ava Weiner and Kenneth D. Camps as Jewish Socializing Roseman, editors Lone Stars of Experiences David: The Jews of Texas Ori Z. Soltes Fixing the World: Jewish Jack Wertheimer, editor Family American Painters in the Twentieth Matters: Jewish Education in an Century Age of Choice Gary P. Zola, editor The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Jacob Edward S. Shapiro Crown Heights: Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Jewry Riot David Zurawik The Jews of Prime Time Kirsten Fermaglich American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: Ranen Omer-Sherman, 2002 Diaspora Early Holocaust Consciousness and and Zionism in Jewish American Liberal America, 1957–1965 Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth Andrea Greenbaum, editor Jews of Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, South Florida editors, 2001 Jews of Brooklyn Sylvia Barack Fishman Double or Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed editors Women and American Marriage Judaism: Historical Perspectives George M. -

Newsletter International Council of Jewish Women: 5655 Silver Creek Valley Road #480, San Jose, CA 95138 U.S.A

April 2014 – Nisan 5774 Newsletter International Council of Jewish Women: 5655 Silver Creek Valley Road #480, San Jose, CA 95138 U.S.A. Website: www.icjw.org Email: [email protected] Tel: +1 408 274 8020 Dear Friends: Just as with all things in our lives, there is indeed a “cycle” in the life of all organizations, including the International Council of Jewish Women. These cycles have one overriding purpose: renewal. In order to grow and move forward, renewal is essential; renewal brings new insights, new energies, new commitment and the opportunity for new growth to our organization and we welcome it. The spring of 2014 is ICJW’s “moment of renewal”. We will welcome new leadership; we will welcome new ideas; we will welcome new energies, and we will offer recognition and honor to those women who have led (and in many cases continue to lead) our organization. This edition of the ICJW Newsletter celebrates this renewal and those who have brought us to this point in our history. As we look forward to our Quadrennial Convention in Prague in May, we are proud to introduce our six newest Honorary Life Members, who will be officially recognized at the Convention, together with the installation of our new leaders. As in past editions, we feature two of our affiliates – the National Council of Jewish Women in Australia, the “home affiliate” of our incoming President, Robyn Lenn; and the Voluntarias Judeo Mexicanas – our rejuvenated affiliate in Mexico. We feature our ongoing efforts at the United Nations, including three exciting programs that we presented at the recent UN Commission on the Status of Women in New York, and our campaigns at the UN and through our affiliates around the world to fight against the reprehensible practice of trafficking. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print t>leedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to t>e removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in ttie original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI* CHARITY WORK AS NATION-BUILDING: AMERICAN JEWISH WOMEN AND THE CRISES DSr EUROPE AND PALESTINE, 1914-1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mary McCune, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Susan M. -

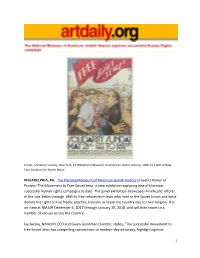

The Movement to Free Soviet Jews, a New Exhibition Exploring One of the Most Successful Human Rights Campaigns to Date

Poster, Solidarity Sunday, New York, 1978 National Museum of American Jewish History, 1990.49.1 Gift of New York Coalition for Soviet Jewry. PHILADELPHIA, PA.- The National Museum of American Jewish History presents Power of Protest: The Movement to Free Soviet Jews, a new exhibition exploring one of the most successful human rights campaigns to date. The panel exhibition showcases Americans’ efforts in the late 1960s through 1990 to free refuseniks—Jews who lived in the Soviet Union and were denied the rights to live freely, practice Judaism, or leave the country due to their religion. It is on view at NMAJH December 6, 2017 through January 15, 2018, and will then travel to a number of venues across the country. Ivy Barsky, NMAJH’s CEO and Gwen Goodman Director, states, “The successful movement to free Soviet Jews has compelling connections to modern-day advocacy, highlighting how 1 grassroots efforts can have an enormous impact. This exhibition serves as a reminder of how individuals can help preserve, protect, and expand America’s unique promise of religious freedom, even for individuals on the other side of the world.” Power of Protest: The Movement to Free Soviet Jews walks visitors through the human rights campaign that took place on behalf of Soviet Jews, one that brought together organizations, student activists, community leaders, and thousands of individuals—and reached the highest echelons of the American government. Americans staged public demonstrations across the country, held massive rallies, and called for politicians to speak out. The exhibition celebrates the struggles and successes of this movement, as well as the experiences of Jewish emigrants from the U.S.S.R. -

10Th Triennial Convention

INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEWISH WOMEN 10th Triennial Convention THEME- "The Jewish Woman in Tomorrow's World" ST MAY, 1975־25TH APRIL 1 MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA I THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE Library ת BI a u s t e i I INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL OF JEWISH WOMEN I. C. J. W. TRIENNIAL CONVENTION ־ May 1 1975 ־ April 25 INDEX Pages Affiliates of ICJW 3-4 5 ־ ICJW Officers, 1972 1975 Chairmen of ICJW Committees 6 ־10th. International Convention Committee 7 8 ־ List of Delegates and Participants 9 11 Convention Program 12 - 16 Pre-Convention Executive Meeting 17-20 Official Opening banquet 21 ־Dr. Herczeg's opening address 21 23 Greetings 23-24 Opening Session 25 Rules for the Convention 25 - 27 Roll Call - Credential Report 28 In Memoriam 29 -31 President's Report 32 - 42 ־ 42־Treasurer's Report 48 Extension and Field Service Committee's Report 48-51 European Committee's Report 52 - 54 Session : "Future Status and Role of the Jewish Women" 55 - 62 Session : "Israel and the Jewish People" 63 - 81 Monday, 28th April 1975 82 ־Session : "Community Services" 83 89 Report of !-he Ways and Means Committee 90 ־Session : "Jewish Education" 91 104 י United Nations Session 105-113 Session dedicated to International Women's Year 114-118 ־ New York 119 121 ־ Report by ICJW United Nations Representative Report by ICJW Representative at UNICEF 122-123 Report by ICJW Representative at United Nations - Geneva 123-124 Report by ICJW Representative at UNESCO - Paris 125-130 Report by ICJW Representative at the Council of Europe 131 - 135 Business Session - Resolutions -

Opening the Torah to Women: the Transformation of Tradition

Opening the Torah to Women: The Transformation of Tradition Women are a people by themselves -Talmud: Shabbat 62a Traditional Judaism believes that both men and women have differentiated and distinct roles delegated through the Torah. A man’s role is focused on positive time-bound mitzvot (commandments), which include but are not limited to, daily praying, wrapping tefillin and putting on a tallit; whereas a women’s role and mitzvot are not time bound and include lighting Shabbat candles, separating a piece of challah for G-d on Shabbat, and the laws of Niddah (menstruation purity). 1 Orthodox Judaism views the separate roles of men and women as a valued and crucial aspect of Jewish life and law, whereas Jewish feminism and more reform branches of Judaism believe these distinctions between men and women are representative of sexual discrimination and unequal opportunity in Judaism. The creation of the Reform and Conservative movement in the late 1800s paved the way for the rise of the Jewish feminist movement in the 1970s, which re-evaluated the classical Jewish texts and halakha (Jewish law) in relation to the role of women in Judaism. Due to Judaism’s ability to evolve and change throughout time, women associated with different Jewish denominations have been able to create their own place within Judaism while also maintaining the traditional aspects of Judaism in order to find a place which connects them most to their religiosity and femininity as modern Jewish women. In Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism), there is a teaching that states that when each soul is created it contains both a female and male soul. -

To All the Boys Who Are Emotionally Sixteen Shifra Lindenberg Web & Social Media Manager Dear Boys, Commit to One Person

WWW.YUOBSERVER.ORG Volume LXV Issue III November 2018 To All the Boys who are Emotionally Sixteen Shifra Lindenberg Web & Social Media Manager Dear boys, commit to one person. I agree with to these relationships that you keep them happy. She’ll find someone Yes, boys. Not men, not guys, you on that. However, the real forming, boys. If the girl feels the who sees her for the incredible boys. Because you didn’t really reason you aren’t ready is that you same as you, in just wanting to individual that she is and puts in the become a man when you turned don’t want to be ready. have companionship so she isn’t work to love her because he loves thirteen, you didn’t completely find You’re comfortable in your lonely, and not because she loves her. yourself during your gap year - if fleeting relationships with girls that you, there may not be damage But you? You’ll keep searching you did take one - and you aren’t hold little to no real commitment. because she wasn’t emotionally for someone who’ll temporarily fill grown up now. It’s so much easier to have a invested in you. You used her, and your void of loneliness, like you’ve Because you’re still growing pseudo-serious relationship with a she used you. But if the girl cared been doing since high school. up. You’re either just turning twenty girl for six to eight months than to about and invested in you, she’ll That’s why you’re emotionally or you’re in your early twenties. -

Jewish Women in Britain by Marlena Schmool

Jewish Women in Britain by Marlena Schmool n giving an overview of Jewish women in Great Britain I intend to touch on three areas: Jewish Iorganisations; participation in synagogue life; and the position of Jewish women’s research in Britain. Naturally, what I have to say will scarcely skim the surface of each topic. The main sources for the data I quote are the regular compilations of synagogue membership and estimates of population which the Board of Deputies Community Research Unit has conducted regularly the past thirty years; and two recent large scale-studies: The Review of Women in the Jewish Community in 1993 for the Chief Rabbi’s Commission on Women; and The Survey of Social Attitudes of British Jews conducted by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research in 1995. In common with other “western” communities, British Jewry is based on immigrants. Its modern history is usually dated from 1656 with the settlement in London of a small group of sephardi Jews from Holland who were quickly followed by co-religionists of ashkenazi stock coming either directly from Germany or via Holland.1 The community continued to grow slowly and by 1800 was estimated at between 20,000 and 25,000.2 By the early 1880s, with an escalating influx from Eastern and Central Europe, British Jewry numbered a little over 60,000.3 Immigrant and native-born alike lived mainly in London, originally concentrating in the Spitalfields and Aldgate/Whitechapel areas at the eastern boundary of the City of London. Between 1880 and 1914 the immigrants and their first-generation British-born children led to a community numbering 300,000.4 Leaders of the established community responded to increased immigration by attempting “to turn the immigrants into Englishmen of the Jewish persuasion” and if this was not possible for the adults, then certainly it was to be attempted for the children.5 From the point of view of acculturated British Jewry, the acceptance they had laboured long to earn seemed threatened by newcomers with strange customs who did not readily blend into the late-Victorian English scene. -

Ifiivsletter

fe^ssbciation for Jewish Studies IfiiVSLETTER Number 45 Fall 1995 25-Year Report of the Executive Secretary From the Seventh Annual Conference, 1975 From the Twenty-Sixth Annual Conference, 1994 Standing, 1. to r.: Charles and Judith Berlin, Frank Talmage, Ismar Schorsch Left to right: Bernard Cooperman, Jehuda Reinharz, Marvin Fox, Seated, 1. to r.: Marvin and June Fox, Salo and Jeanette Baron, Arnold Band Charles and Judith Berlin, Herbert Paper, Arnold Band, Robert Seltzer members, the premier association in its 25-Year Report IN THIS ISSUE field. of the Executive Secretary It has been a quarter-century of Page 1 Charles Berlin enormous achievement. This, our 26th 25-Year Report Harvard University annual conference has 74 sessions and of the Executive Secretary some 300 individuals on the program; in AT THE ANNUAL BANQUET of the AJS on 1973, at our Fifth conference there were Page 6 December 18, 1994, Charles Berlin pre- 8 sessions and 24 names on the program. Gender and Women's Studies sented his report on the state of the Associa- As of this evening, we have some 600 tion after twenty-five years. His report is conference registrations. At our Tenth Page 8 followed here by the edited remarks of the annual conference, in 1978, we had 210 Pedagogy at the AJS current and former officers of the organi- members registered at the conference. zation who spoke on that occasion. After The annual conference of the AJS has Page 10 twenty-two years as Executive Secretary, become the primary meeting for the Jewish Music in the Curriculum Dr. -

We'd Like to Know

We’d Like to Know • If your address changes: Name __________________________________________________________________________________________ Address ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ • If a colleague or friend would like our newsletter: No. 49 2006 – 2007 Name __________________________________________________________________________________________ Address ________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Mail this form to: Ms. Gail Summerhill Department of History The Ohio State University 130 Dulles Hall 230 W. 17th Avenue Columbus, Ohio 43210-1367 Non Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID Columbus, Ohio Permit No. 711 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Department Of History 106 Dulles Hall 230 W. 17th Avenue Columbus, OH 43210-1367 Address service requested 05570-011000-61804-news In This Issue Greetings from the Chair.............................................................. 3 Editorial Staff New Appointments and Growing Programs Professor James Genova Founding of the Faculty of Color Caucus............................................ 5 Professor Matt Goldish Professor Stephanie Smith Archaeological Museum...................................................................... 7 Gail Summerhill New Appointments.............................................................................