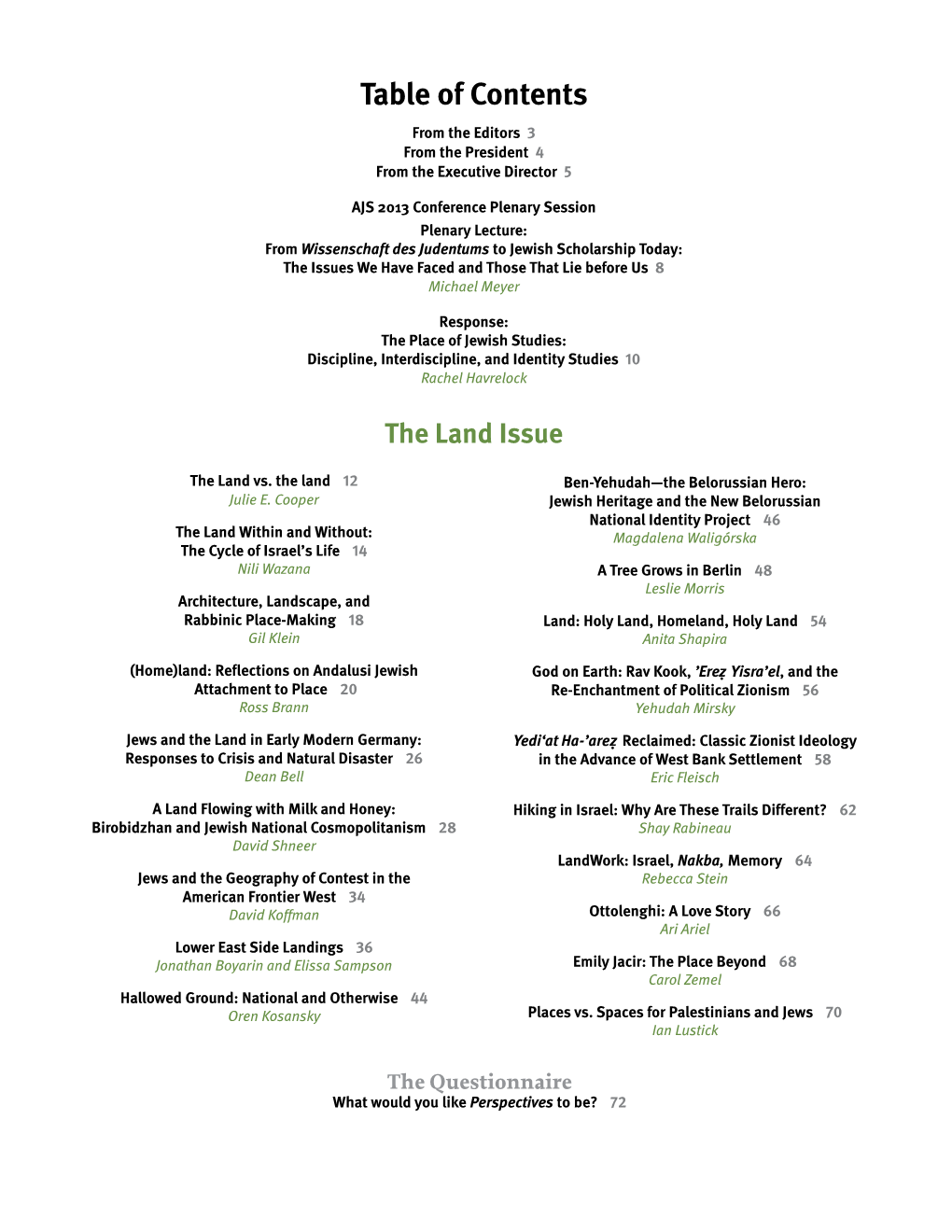

Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When Scholarship Disturbs Narrative: Ian Lustick on Israel's Migration

FORUM When Scholarship Disturbs Narrative Ian Lustick on Israel’s Migration Balance Comment by Sergio DellaPergola ABSTRACT: In response to Ian Lustick’s article on Israel’s migration bal- ance in the previous issue of Israel Studies Review, I question the author’s (lack of) theoretical frame, data handling, and conclusions, all set up against a robust narrative. I show that, until 2010, Israel displayed a posi- tive, if weakened, migration balance and that immigration trends contin- ued to reflect conditions among Diaspora Jewish populations more than Israel’s absorption context. Emigration rates from Israel, while admittedly difficult to measure, were objectively moderate and proportionally lower, for example, than those of Switzerland, a more developed country of similar size, or those of ethnic Germans returning to and then again leav- ing Germany. The main determinants of emigration from Israel—namely, ‘brain drain’—consistently related to socio-economic changes and not to security. I also reject Lustick’s assumptions about the ideological bias of Israel’s research community when dealing with international migration. Scholarship about Israel should not ignore global contextualization and international comparisons. KEYwords: aliyah, economy, emigration, immigration, Israel, Lustick, security, yeridah, Zionism The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but is a practical question. Man must prove the truth—i.e., the reality and power, the this-sidedness of his thinking, in practice. The dispute over the reality or non-reality of thinking that is isolated from practice is a purely scholastic question. — Marx, Theses on Feuerbach Don’t confuse us with your data: we know the situation. -

December Layout 1

Vol. 38-No. 2 ISSN 0892-1571 November/December 2011-Kislev/Tevet 5772 PRESERVING THE PAST – GUARDING THE FUTURE: 30 YEARS OF ACHIEVEMENT ANNUAL TRIBUTE DINNER OF THE AMERICAN & INTERNATIONAL SOCIETIES FOR YAD VASHEM he annual gathering of the American passed on but whose spirit joins us on this and prejudice. We are always pleased to the imperative of Holocaust remembrance Tand International Societies for Yad joyous occasion. I am proud to see how far have with us and recognize the major lead- and thus help ensure that no nation – any- Vashem is an experience in remembrance we have come since that first meeting, ership of this spectacular 800 member as- where, anytime – should ever again suffer and continuity. This year the organization thanks to the generosity of all who are here sociation. a calamity of the unprecedented nature is celebrating its thirtieth anniversary. At tonight and those we remember with love. “The Young Leadership Associates are and scope that befell our people some 70 the Tribute Dinner that was held on No- We witness the growth of Yad Vashem, its the guardians of the future and will be re- years ago in Europe,” said Rabbi Lau. vember 20 at the Sheraton Hotel in New many sites and museums built, and pro- sponsible for ensuring our legacy. Recognizing the tremendous contribu- York, survivors were joined by the genera- grams established, through our efforts. “Our thoughts tonight are bittersweet; we tion of the Societies’ chairman Eli tions that are their inheritors of Jewish con- “And we see our future leaders, the remember our loved ones and all which Zborowski to the cause of Holocaust re- tinuity. -

Jacob Saar Yagil Henkin Hike the Land of Israel

Jacob Saar Yagil Henkin Hike the land of Israel Israel National Trail Includes for download: The Jerusalem trail Recommended Alternate Routes And the Best 25 day hikes in Israel Reviewed by Dany Gaspar Third Edition Copyright © Jacob Saar All rights reserved. It is expressly forbidden to copy, reproduce, photograph, record, digitize, disseminate, store in a database, restore or record by any electronic, optical or mechanical means any part of the book, without written permission from the copyright owner. Printed in Israel Although the authors have taken all reasonable care in preparing this book, the authors and publishers make no warranty about the accuracy or completeness of its content and, to the maximum extent permitted, disclaim all liability arising from its use. Copyrights for maps in this guide: All Rights Reserved by the Survey of Israel 2017. The maps are printed with Survey of Israel permission. Survey of Israel is an Agency for Geodesy, Cadastre, Mapping and Geographical Information and is an Official Agency of the Government of the State of Israel. For most recent updates about changes to trail, to find a hiking partner, your comments to the guide and any other INT related issue please visit the forum. Forum: http://israeltrail.myfastforum.org ISBN 978-965-42046-6-8 Important Links The Jerusalem trail guide & maps: http://israeltrail.myfastforum.org/forum54.php Recent changes to the trail: http://israeltrail.myfastforum.org/forum43.php Recommended INT alternate routes: http://israeltrail.myfastforum.org/forum54.php Forum: http://israeltrail.myfastforum.org Website in English: http://israeltrail.net Website in German: http://www.israel-trail.com . -

Avner Shalev ( Hebrew

(born 1939 ,אבנר שלו : Avner Shalev ( Hebrew Avner Shalev has been Chairman of the Yad Vashem Directorate since 1993. From the beginning of his tenure, Shalev has strived to redefine Holocaust remembrance and education, introducing a far-reaching multiyear redevelopment plan with the goal of preparing Yad Vashem to meet the challenges of Holocaust commemoration in the 21st century. To that end, he has put education at the forefront of Yad Vashem’s activities by opening the International School for Holocaust Studies, as well as enlarging Yad Vashem’s archives and research facilities, and building a new Museum Complex. He is Chief Curator of the landmark Holocaust History Museum that opened in 2005, and of Yad Vashem's permanent exhibit in the Jewish Block at the Auscwitz-Birkenau State Museum, which opened in 2013. He has lead the uploading of Yad Vashem’s Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names onto the Internet, harnessing modern technology in the service of Holocaust remembrance and education. In 2003, Shalev accepted the Israel Prize on behalf of Yad Vashem, in recognition of Yad Vashem’s special contribution to State of Israel. In 2007, Shalev was awarded the Legion of Honor by French President Nicolas Sarkozy for his efforts on behalf of Holocaust awareness worldwide, and also accepted Spain’s Prince of Asturias Award for Concord on behalf of Yad Vashem. In 2011 he received the Worthy of Jerusalem Award from the City of Jerusalem. In 2014 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Distinction by Israeli President Shimon Peres, for his outstanding contribution to the State of Israel and to humanity. -

Sept. 30 Issue Final

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday September 30, 2003 Volume 50 Number 6 www.upenn.edu/almanac Two Endowed Chairs in Political Science Dr. Ian S. Lustick, professor of political director of the Solomon Asch Center for Study ternational Organization, and Journal of Inter- science, has been appointed to the Bess Hey- of Ethnopolitical Conflict. national Law and Politics. The author of five man Professorship. After earning his B.A. at A specialist in areas of comparative politics, books and monographs, he received the Amer- Brandeis University, Dr. Lustick completed international politics, organization theory, and ican Political Science Associationʼs J. David both his M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Middle Eastern politics, Dr. Lustick is respon- Greenstone Award for the Best Book in Politics California, Berkeley. sible for developing the computational model- and History in 1995 for his Unsettled States, Dr. Lustick came to ing platform known as PS-I. This software pro- Disputed Lands: Britain and Ireland, France Penn in 1991 following gram, which he created in collaboration with and Algeria, Israel and the West Bank-Gaza. In 15 years on the Dart- Dr. Vladimir Dergachev, GEngʼ99, Grʼ00, al- addition to serving as a member of the Council mouth faculty. From lows social scientists to simulate political phe- on Foreign Relations, Dr. Lustick is the former 1997 to 2000, he served nomena in an effort to apply agent-based model- president of the Politics and History Section of as chair of the depart- ing to public policy problems. His current work the American Political Science Association and ment of political sci- includes research on rights of return in Zionism of the Association for Israel Studies. -

Emily Jacir: Europa 30 Sep 2015 – 3 Jan 2016 Large Print Labels and Interpretation Galleries 1, 8 & 9

Emily Jacir: Europa 30 Sep 2015 – 3 Jan 2016 Large print labels and interpretation Galleries 1, 8 & 9 1 Gallery 1 Emily Jacir: Europa For nearly two decades Emily Jacir has built a captivating and complex artistic practice through installation, photography, sculpture, drawing and moving image. As poetic as it is political, her work investigates movement, exchange, transformation, resistance and silenced historical narratives. This exhibition focuses on Jacir’s work in Europe: Italy and the Mediterranean in particular. Jacir often unearths historic material through performative gestures and in-depth research. The projects in Europa also explore acts of translation, figuration and abstraction. (continues on next page) 2 At the heart of the exhibition is Material for a film (2004– ongoing), an installation centred around the story of Wael Zuaiter, a Palestinian intellectual who was assassinated outside his home in Rome by Israeli Mossad agents in 1972. Taking an unrealised proposal by Italian filmmakers Elio Petri and Ugo Pirro to create a fi lm about Zuaiter’s life as her starting point, the resulting installation contains documents, photographs, and sound elements, including Mahler’s 9th Symphony as one of the soundtracks to the work. linz diary (2003), is a performance by Jacir captured by one of the city’s live webcams that photographed the artist as she posed by a fountain in a public square in Linz, Austria, at 6pm everyday, over 26 days. During the performance Jacir would send the captured webcam photo of herself to her email list along with a small diary entry. In the series from Paris to Riyadh (drawings for my mother) (1998–2001), a collection of white vellum papers dotted with black ink are delicately placed side by side. -

Wertheimer, Editor Imagining the Seth Farber an American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B

Imagining the American Jewish Community Brandeis Series in American Jewish History, Culture, and Life Jonathan D. Sarna, Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor For a complete list of books in the series, visit www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSAJ.html Jack Wertheimer, editor Imagining the Seth Farber An American Orthodox American Jewish Community Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph B. Murray Zimiles Gilded Lions and Soloveitchik and Boston’s Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to Maimonides School the Carousel Ava F. Kahn and Marc Dollinger, Marianne R. Sanua Be of Good editors California Jews Courage: The American Jewish Amy L. Sales and Leonard Saxe “How Committee, 1945–2006 Goodly Are Thy Tents”: Summer Hollace Ava Weiner and Kenneth D. Camps as Jewish Socializing Roseman, editors Lone Stars of Experiences David: The Jews of Texas Ori Z. Soltes Fixing the World: Jewish Jack Wertheimer, editor Family American Painters in the Twentieth Matters: Jewish Education in an Century Age of Choice Gary P. Zola, editor The Dynamics of American Jewish History: Jacob Edward S. Shapiro Crown Heights: Rader Marcus’s Essays on American Blacks, Jews, and the 1991 Brooklyn Jewry Riot David Zurawik The Jews of Prime Time Kirsten Fermaglich American Dreams and Nazi Nightmares: Ranen Omer-Sherman, 2002 Diaspora Early Holocaust Consciousness and and Zionism in Jewish American Liberal America, 1957–1965 Literature: Lazarus, Syrkin, Reznikoff, and Roth Andrea Greenbaum, editor Jews of Ilana Abramovitch and Seán Galvin, South Florida editors, 2001 Jews of Brooklyn Sylvia Barack Fishman Double or Pamela S. Nadell and Jonathan D. Sarna, Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed editors Women and American Marriage Judaism: Historical Perspectives George M. -

The Hebrew-Jewish Disconnection

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects College of Graduate Studies 5-2016 The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection Jacey Peers Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses Part of the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Peers, Jacey. (2016). The eH brew-Jewish Disconnection. In BSU Master’s Theses and Projects. Item 32. Available at http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses/32 Copyright © 2016 Jacey Peers This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. THE HEBREW-JEWISH DISCONNECTION Submitted by Jacey Peers Department of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages Bridgewater State University Spring 2016 Content and Style Approved By: ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Joyce Rain Anderson, Chair of Thesis Committee Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Anne Doyle, Committee Member Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Julia (Yulia) Stakhnevich, Committee Member Date 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my mom for her support throughout all of my academic endeavors; even when she was only half listening, she was always there for me. I truly could not have done any of this without you. To my dad, who converted to Judaism at 56, thank you for showing me that being Jewish is more than having a certain blood that runs through your veins, and that there is hope for me to feel like I belong in the community I was born into, but have always felt next to. -

March 2021 ACADEMIC BIOGRAPHY Lynn Keller E-Mail: Rlkeller@Wisc

March 2021 ACADEMIC BIOGRAPHY Lynn Keller E-mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D., University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1981 Dissertation: Heirs of the Modernists: John Ashbery, Elizabeth Bishop, and Robert Creeley, directed by Robert von Hallberg M.A., University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, 1976 B.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, 1973 Academic Awards and Honors: Bradshaw Knight Professor of Environmental Humanities (while director of CHE, 2016-2019) Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, 2015-2016 Martha Meier Renk Bascom Professor of Poetry, January 2003 to August 2019; emerita to present UW Institute for Research in the Humanities, Senior Fellow, Fall 1999-Spring 2004 American Association of University Women Fellowship, July 1994-June 1995 Vilas Associate, 1993-1995 (summer salary 1993, 1994) Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching, 1989 University nominee for NEH Summer Stipend, 1986 Fellow, University of Wisconsin Institute for Research in the Humanities, Fall semester 1983 NEH Summer Stipend, 1982 Doctoral Dissertation awarded Departmental Honors, English Department, University of Chicago, 1981 Whiting Dissertation Fellowship, 1979-80 Honorary Fellowship, University of Chicago, 1976-77 B.A. awarded “With Distinction,” Stanford University, 1973 Employment: 2016-2019 Director, Center for Culture, History and Environment, Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, UW-Madison 2014 Visiting Professor, Stockholm University, Stockholm Sweden, Spring semester 2009-2019 Faculty Associate, Center for Culture, History, and Environment, UW-Madison 1994-2019 Full Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison [Emerita after August 2019] 1987-1994 Associate Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1981-1987 Assistant Professor, English Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1981 Instructor, University of Chicago Extension (course on T.S. -

Latkes Traditional Latkes Are Made of Shredded, White Potatoes. They Are the Richer Brother of Potato Pancakes, a German Staple

Latkes Traditional latkes are made of shredded, white potatoes. They are the richer brother of potato pancakes, a German staple. There are endless variations. Any veggie can be used to make latkes. As for me, I’m a lazy cook, so I’ve assembled a latke using frozen, shredded hash browns. Here is a traditional latke recipe, although there are many out there, and my shortcut version. Bon Appetit. Traditional Latkes 1 pound of potatoes, peeled or not, shredded ½ cup finely chopped onion 1 egg ½ tsp. salt pinch black pepper oil for frying sour cream applesauce Rinse the shredded potatoes. If you shred them in advance, cover with cold water. Mix all ingredients except oil. Heat oil, ½ inch deep. (It should pop when you put a drop of water in, but be careful! Too hot and the latkes will burn before they cook inside.) Take a scoop of the mixture and pat it into a flat, 3 inch pattie, about ½ inch thick. The sides should not be thinner than the middle. Fry a few at a time, turning when the bottom gets brown. Remove to a plate with paper towels to soak up the excess oil. Eat these puppies warm with sour cream and applesauce. I know this sounds like a terrible combination to anyone who has not had latkes, but try it. You’ll like it. This recipe doesn’t call for matzo meal, but I always use some. Be sure you let the mixture stand a while before shaping, if you add matzo meal, so the matzo meal binds to the rest of the ingredients. -

Memory Trace Fazal Sheikh

MEMORY TRACE FAZAL SHEIKH 2 3 Front and back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°50 41”N / 35°13 47”E Israeli side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of Neve Yaakov and Beit Ḥanīna. Just beyond the wall lies the neighborhood of al-Ram, now severed from East Jerusalem. Inside front and inside back cover image: ‚ ‚ 31°49 10”N / 35°15 59”E Palestinian side of the Separation Wall on the outskirts of the Palestinian town of ʿAnata. The Israeli settlement of Pisgat Ze’ev lies beyond in East Jerusalem. This publication takes its point of departure from Fazal Sheikh’s Memory Trace, the first of his three-volume photographic proj- ect on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Published in the spring of 2015, The Erasure Trilogy is divided into three separate vol- umes—Memory Trace, Desert Bloom, and Independence/Nakba. The project seeks to explore the legacies of the Arab–Israeli War of 1948, which resulted in the dispossession and displacement of three quarters of the Palestinian population, in the establishment of the State of Israel, and in the reconfiguration of territorial borders across the region. Elements of these volumes have been exhibited at the Slought Foundation in Philadelphia, Storefront for Art and Architecture, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and the Pace/MacGill Gallery in New York, and will now be presented at the Al-Ma’mal Foundation for Contemporary Art in East Jerusalem, and the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center in Ramallah. In addition, historical documents and materials related to the history of Al-’Araqīb, a Bedouin village that has been destroyed and rebuilt more than one hundred times in the ongoing “battle over the Negev,” first presented at the Slought Foundation, will be shown at Al-Ma’mal. -

Discovering the Other Judeo-Spanish Vernacular

ḤAKETÍA: DISCOVERING THE OTHER JUDEO-SPANISH VERNACULAR ALICIA SISSO RAZ VOCES DE ḤAKETÍA “You speak Spanish very well, but why are there so many archaic Cervantes-like words in your vocabulary?” This is a question often heard from native Spanish speakers regarding Ḥaketía, the lesser known of the Judeo-Spanish vernacular dialects (also spelled Ḥakitía, Ḥaquetía, or Jaquetía). Although Judeo-Spanish vernacular is presently associated only with the communities of northern Morocco, in the past it has also been spoken in other Moroccan regions, Algeria, and Gibraltar. Similar to the Djudezmo of the Eastern Mediterranean, Ḥaketía has its roots in Spain, and likewise, it is composed of predominantly medieval Castilian as well as vocabulary adopted from other linguistic sources. The proximity to Spain, coupled with other prominent factors, has contributed to the constant modification and adaptation of Ḥaketía to contemporary Spanish. The impact of this “hispanization” is especially manifested in Haketía’s lexicon while it is less apparent in the expressions and aphorisms with which Ḥaketía is so richly infused.1 Ladino, the Judeo-Spanish calque language of Hebrew, has been common among all Sephardic communities, including the Moroccan one, and differs from the spoken ones.2 The Jews of Spain were in full command of the spoken Iberian dialects throughout their linguistic evolutionary stages; they also became well versed in the official Spanish dialect, Castilian, since its formation. They, however, have continually employed rabbinical Hebrew and Aramaic 1 Isaac B. Benharroch, Diccionario de Haquetía (Caracas: Centro de Estudios Sefardíes de Caracas, 2004), 49. 2 Haїm Vidal Séphiha, “Judeo-Spanish, Birth, Death and Re-birth,” in Yiddish and Judeo-Spanish, A European Heritage, ed.