(Eds.) Security Sector Governance in the Western Balkans: Self-Assessment S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Itineraries Rousseau, N. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Rousseau, N. (2019). Itineraries: A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Itineraries A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen op woensdag 20 maart 2019 om 15.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Nicky Rousseau geboren te Dundee, Zuid-Afrika promotoren: prof.dr. -

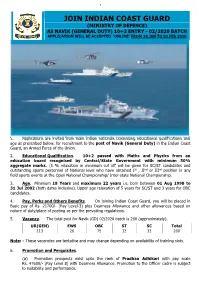

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

Intelligence Services in the National Security System: the Case Of

ELIAMEP Occasional Papers OP07.03 INTELLIGENCE SERVICES IN THE NATIONAL SECURITY SYSTEM : THE CASE OF EYP OP07.03 by Pavlos Apostolidis1 1 Ambassador (ret.), former Director of the National Intelligence Service (1999-2004) & Special Advisor of ELIAMEP - 1 - ELIAMEP Occasional Papers OP07.03 Copyright © 2007 HELLENIC FOUNDATION FOR EUROPEAN AND FOREIGN POLICY (ELIAMEP) All rights reserved ISBN 978-960-8356-22-1 INTELLIGENCE SERVICES IN THE NATIONAL SECURITY SYSTEM : THE CASE OF EYP by Pavlos Apostolidis Ambassador (ret.), former Director of the National Intelligence Service (1999-2004) Special Advisor of ELIAMEP OP07.03 HELLENIC FOUNDATION FOR EUROPEAN & FOREIGN POLICY (ELIAMEP) 49 Vas. Sofias Av. 106 76 Athens, Greece Τel: (+30) 210 7257110 Fax: (+30) 210 7257114 e-mail: [email protected] url: http://www.eliamep.gr _______________________________________________________________ The Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) was founded in 1988 and operates as an independent, non- profit, policy- oriented research and training institute. It functions as a forum of debate on international issues, as an information centre, as well as a point of contact for experts and policymakers. Over the years, ELIAMEP has developed into and influential think-tank on foreign policy and international relations issues. ELIAMEP neither expresses, nor represents, any specific political party view. It is only devoted to the right of free and well- documented discourse. 2 ELIAMEP Occasional Papers OP07.03 INTRODUCTION In February 2006, the Greek Government divulged at a press conference that a large number of Vodafone mobile telephones belonging to members of the Government, the Security Services and others, had been illegally tapped. -

Execution of Imprisonment for Women in the Republic of Kosovo

Leka and Leka: Judiciary and State-Building of Kosovo: Execution of Imprisonment International Journal on Responsibility 2.1 Dec 2018 Judiciary and State-Building of Kosovo: the Execution of Imprisonment for Women in the Republic of Kosovo Saranda Leka, University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina” Dukagjin Leka, University of Gjilan “Kadri Zeka” Abstract Historically it is known that criminal offenses made by females are at a lower level than criminal offenses made by males. However, regardless of gender, it is important to note that for the perpetrators of criminal offenses have also been created the legal basis, and earlier has been used also the customary law, in order to sanction these criminal offenses. But, the main problem throughout the history of mankind has been that through the execution of these sanctions is the re-socialization of those persons achieved, especially for the females, as well as the issue of the physical aspect of the place, where the females should be held, in special prisons or together with other perpetrators of criminal offenses. When considering the penitentiary system in Kosovo, for females who in one way or another have committed a crime and been punished with a prison sentence, it is notable that from the moment they begin serving the sentence, they should be sent to a special prison for women in Kosovo, known as the Lipjan Prison, which is located around 15 kilometers from the capital of Kosovo – Pristina. In this paper, we will try to elaborate historical aspects of the development of the prison for women during the state-building of Kosovo, then the legal basis on which the sentence is served, and we shall not neglect studying and presenting most of the aspects related to the functioning of the single prison for women during the state-building of the Republic of Kosovo. -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

3. Security-Intelligence Services in the Republic of Serbia Bogoljub Milosavljević and Predrag Petrović

3. Security-Intelligence Services in the Republic of Serbia Bogoljub Milosavljević and Predrag Petrović The Security-intelligence services (hence the intelligence services) are among the most important executive actors in any national security systems. In this chapter the term intelligence services denotes only specialised civilian and mili- tary organisations with security-intelligence functions, established within the state apparatus and operating under government control. Intelligence serv- ices should, first of all, provide state bodies with timely, relevant and precise 208 information. They should protect the constitutional order and national interests against penetration by foreign intelligence services and activities of organised criminal and terrorist groups. They are authorised to collect information from public sources, and can use secret methods, techniques and means.285 There are three organisations in Serbia with these responsibilities; the Secu- rity-Information Agency (SIA), the Military Security Agency (MSA) and the Mili- tary Intelligence Agency (MoI). The SIA is directly subordinated to the govern- ment and has the status of a special republic organisation, while both the MSA and MoI are organisational units (administrative bodies) within the Ministry of Defence (MoD) subordinated to the defence minister, and thus also to the gov- ernment. The functions of the intelligence services are specified by positive legal regulations286 and include the usual intelligence activities: 1. The collection and analysis of data relevant for national security, defence and protection of eco- 285 Reconciling the secrecy needs of intelligence services with the fundamental tenets of democ- racy is an important question. In order words, how can this secrecy be reconciled with transpar- ency of state institutions. -

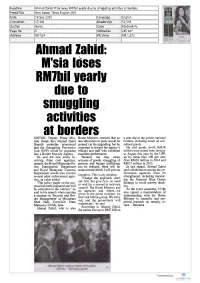

Rm7bll Yearly Smuggling

Headline Ahmad Zahid M'sia loses RM7bil yearly due to smuggling activities at borders MediaTitle New Sabah Times English (KK) Date 18 Sep 2015 Language English Circulation 17,182 Readership 51,546 Section Home Color Black/white Page No 5 ArticleSize 245 cm² AdValue RM 524 PR Value RM 1,572 Ahmad lahid: M'sla loses RM7bll yearly due to smuggling activities at borders SINTOK: Deputy Prime "Min Home Minister, stressed that no a year due to the porous national ister Datuk Seri Ahmad Zahid new allocation or posts would be borders, including losses oh sub Hamidi yesterday announced created via the upgrading, but he sidised goods. that the Smuggling Prevention promised to reward the agency's He said goods worth RM38 Unit (UPP) would be upgraded officers and staff who exhibited million were seized from January into a Border Security Agency. excellent performance. to August this year by the UPP, He said the new entity ift "Believe me that when up by more than 100 per cent volving three core agencies, seizures of goods, smuggling of from RM18 million in 2014 and namely, the Royal Malaysian Po persons and human trafficking RM17 million in 2013. lice, Immigration Department can be reduced, there will be In this regard, Ahmad Zahid and Royal Malaysian Customs some reward which I will give as said collaboration among the en Department would also involve forcement agencies must be incentive. This is my promise. several other enforcement agen strengthened, including translat cies, as value added. "Change the approach, don't ing the National Blue Ocean ask first, but give first...no need "The policy paper on the pro to wait for a reward to motivate Strategy to avoid narrow think posal has been prepared and will ing. -

Submission-Mare-Liberum

1 Submission to the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants: pushback practices and their impact on the human rights of migrants by Mare Liberum Mare Liberum is a Berlin based non-profit-association, that monitors the human rights situation in the Aegean Sea with its own ships - mainly of the coast of the Greek island of Lesvos. As independent observers, we conduct research to document and publish our findings about the current situation at the European border. Since March 2020, Mare Liberum has witnessed a dramatic increase in human rights violations in the Aegean, both at sea and on land. Collective expulsions, commonly known as ‘pushbacks’, which are defined under ECHR Protocol N. 4 (Article 4), have been the most common violation we have witnessed in 2020. From March 2020 until the end of December 2020 alone, we counted 321 pushbacks in the Aegean Sea, in which 9,798 people were pushed back. Pushbacks by the Hellenic Coast Guard and other European actors, as well as pullbacks by the Turkish Coast Guard are not a new phenomenon in the Aegean Sea. However, the numbers were significantly lower and it was standard procedure for the Hellenic Coast Guard to rescue boats in distress and bring them to land where they would register as asylum seekers. End of February 2020 the political situation changed dramatically when Erdogan decided to open the borders and to terminate the EU-Turkey deal of 2016 as a political move to create pressure on the EU. Instead of preventing refugees from crossing the Aegean – as it was agreed upon in the widely criticised EU-Turkey deal - reports suggested that people on the move were forced towards the land and sea borders by Turkish authorities to provoke a large number of crossings. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

POLICY for MANAGING ACCESS to INTELLIGENCE INFORMATION in POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA University of the Witwatersrand

POLICY FOR MANAGING ACCESS TO INTELLIGENCE INFORMATION IN POST-APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA Submitted by Sandra Elizabeth Africa In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PhD in Management University of the Witwatersrand Supervisor: Professor Gavin Cawthra September 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages DECLARATION.................................................................................................... v ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………… vi TABLE OF ACRONYMS………………………………………………………. vii CHAPTER 1: AIM OF THE STUDY ………………………………………….. 1 Problem statement………………………………………………………………… 1 Background………………………………………………………………………... 1 Aim of the study…………………………………………………………………. 3 The research questions…………………………………………………………….. 5 Significance of the study………………………………………………………….. 7 Scope of the study………………………………………………………………… 9 Title of the dissertation…………………………………………………………… 12 Structure of the dissertation………………………………………………………. 13 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY……………………………………………. 15 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 15 Main methodological features of the study………………………………………. 16 Underlying assumptions of the study…………………………………………….. 20 The research process……………………………………………………………… 22 The research tools………………………………………………………………… 24 Interpretation of the research results……………………………………………… 28 Concluding remarks………………………………………………………………. 30 CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW …………………………………….. 31 Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 31 Conceptual approaches to secrecy……………………………………………….. 31 Balancing secrecy and access to information in international relations…………. -

Law on Military Security Agency and Military Intelligence Agency

LAW ON MILITARY SECURITY AGENCY AND MILITARY INTELLIGENCE AGENCY I GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1 This Law shall regulate competences, activities, tasks, authority, oversight and control of the Military Security Agency (hereinafter referred to as the MSA) and the Military Intelligence Agency (hereinafter referred to as the MIA), co-operation, as well as other matters of importance for their operations. Article 2 The MSA and the MIA are the administrative bodies within the Ministry of Defence that perform security and intelligence activities of importance for defence and are part of a unified security and intelligence system of the Republic of Serbia. Article 3 The MSA and MIA shall be independent in conducting their activities within their scope of work. The MSA and MIA shall carry out mutual co-operation and exchange data. The method and contents of mutual co-operation and exchange of data stipulated in Paragraph 2 of this Article shall be regulated by the Minister of Defence. The MSA and the MIA shall co-operate and exchange data with competent institutions, organisations, services and bodies of the Republic of Serbia, as well as security services of other states and international organisations in compliance with the Constitution, the Law, other regulations and general acts, defined intelligence and security policy of the Republic of Serbia and ratified international agreements. In their work, the MSA and the MIA shall be neutral in terms of politics, ideology and interest. Article 4 The MSA and MIA shall have the status of a legal entity. The MSA and MIA shall have their insignia, symbols and other signs and marks. -

Democratic Security Sector Governance in Serbia

PRIF-Reports No. 94 Democratic Security Sector Governance in Serbia Filip Ejdus This report was prepared with the kind support of the Volkswagen-Stiftung. Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) 2010 Correspondence to: PRIF Baseler Straße 27-31 60329 Frankfurt am Main Germany Telephone: +49(0)69 95 91 04-0 Fax: +49(0)69 55 84 81 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.prif.org ISBN: 978-3-942532-04-4 Euro 10.- Summary On 5 October 2000, the citizens of Serbia toppled Slobodan Milošević in what came to be known as the “Bulldozer Revolution”. This watershed event symbolizes not only the end of a decade of authoritarian rule but also the beginning of a double transition: from authoritarian rule to democracy, on the one hand, and from a series of armed conflicts to peace, on the other. This transition has thoroughly transformed Serbian politics in general and Serbia’s security sector in particular. This October, Serbia’s democracy celebrated its tenth anniversary. The jubilee is an appropriate opportunity to reflect on the past decade. With this aim in mind, the report will seek to analyse the impact of democratization on security sector governance in Serbia over the period 2000-2010. In order to do so, in the first part of the report we have developed an analytical framework for studying democratic security sector governance, which is defined as the transparent organization and management of the security sector based on the accountability of decision-makers, respect for the rule of law and human rights, checks and balances, equal representation, active civic participation, public agreement and democratic oversight.