Black Settlers Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Docket No. 06-172-U George W. Carpenter

BEFORE THE ARKANSAS PUBLIC SERVICE COMMlSSlON IN TH€ MATTER OF THE APPLICATION OF SOUTHWESTERN ELECTRIC POWER COMPANY 1 FOR A CERTIFICATE OF PUBLIC CONVENIENCE DOCKET NO. 06-172-U AND NECESSITY TO REBUILD AND CONVERT ITS EXISTING 69 KV TRANSMISSION LINE TU 161 KV 1 BETWEEN SWEPCO'S FAYETTEVILLE AND NORTH ) FAYETTEVILLE SUBSTATIONS, ALL LOCATED IN WASHINGTON COUNTY IN ARKANSAS REBUTTAL TESTIMONY OF GEORGE W. CARPENTER March 16,2007 BEFORE THE ARKANSAS PUBLfC SERVICE COMMISSION IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION OF SOUTHWESTERN ELECTRIC POWER COMPANY I G FOR A GERTIFKATE OF PUBLIC CONVENIENCE 1 DOCKET NO.06- I 72. i AND NECESSfTY TO REBUILD AND CONVERT ITS ) 8 EXISTING 69 KV TRANSMlSSlON LINE TO 161 KV ) 9 BETWEEN SWEPCO’S FAYETTEVILLE AND NORTH ) 10 FAYETTEVILLE SUBSTATIONS, ALL LOCATED IN ) 11 WASHfNGTON COUNTY iN ARKANSAS 1 I2 REBUTTAL TESTIMONY OF GEORGE W. CARPENTER 13 Q. Please state your name. 14 A. My name is George W, Carpenter 1s Q. Are you the same George W. Carpenter that filed testimony previously 16 in this case? 17 A. Yes. is Q. Are there corrections to your earlier filed testimony? 19 A. Yes. Throughout my testimony, I make reference to the mute study 20 pehrmed by P8S8J. f have been provided corrected pages 4-28 and 4-29 21 to that study. Those corrected pages are attached hereto and incorporated 22 into my orjginal Exhibit C as though set out therein word fur word. 23 Q. Have you had the opportunity to review the public comments and the 24 Petition to Intervene filed by Irene Pritchard and Thomas Brown? 25 A. -

2040 Metropolitan Transportation Plan

Northwest Arkansas 2040 METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION PLAN Prepared by the Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission in cooperation with the Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department, Missouri Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration March 23, 2016 Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission Membership: City of Avoca City of Bella Vista Benton County City of Bentonville City of Bethel Heights City of Cave Springs City of Centerton City of Decatur City of Elkins City of Elm Springs City of Farmington City of Fayetteville City of Garfield City of Gateway City of Gentry City of Goshen City of Gravette City of Greenland City of Highfill City of Hindsville City of Huntsville City of Johnson City of Lincoln City of Little Flock City of Lowell McDonald County, Missouri City of Pea Ridge City of Pineville, Missouri City of Prairie Grove City of Rogers City of Siloam Springs City of Springdale City of Springtown City of Sulphur Springs City of Tontitown Washington County City of West Fork Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department (AHTD) Missouri Department of Transportation (MODOT) Beaver Water District Ozark Regional Transit Inc. Razorback Transit University of Arkansas ii CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 2 VISION AND GOALS CHAPTER 3 POPULATION AND LANDUSE CHAPTER 4 PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT CHAPTER 5 ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE CHAPTER 6 ENVIRONMENT CHAPTER 7 TRAVEL PATTERNS AND TRAVEL FORECASTING FACILITY DESIGN, MANAGEMENT AND OPERATIONS, CHAPTER 8 AND SYSTEM PERFORMANCE -

A Brief History of South Fayetteville – by J

A Brief History of South Fayetteville – by J. B. Hogan The area of town known as South Fayetteville has a long and interesting history. Most of us know South Fayetteville as the poor side of town, which it has been for nearly all of our history. This is the working class section of Fayetteville, with small, older homes, little corner groceries and neighborhood schools (all of the latter two now nearly defunct). But it wasn’t always where the less affluent citizens of Fayetteville lived – far from it. Much of South Fayetteville, in fact, belonged to one man: arguably the most famous person to ever live here: the second Governor of the State of Arkansas, Archibald Yell. Archibald Yell isn’t just a bypass through the middle of town, he was a living, breathing politician, lawyer and military hero. Yell gained notoriety and the lasting appreciation of Andrew Jackson, Old Hickory, through his military exploits in the War of 1812 and other conflicts in the early years of the nineteenth century. It was President Jackson who gave Yell his first positions in the Arkansas Territory and Yell was also close friends with President James K. Polk, another favorite of Andrew Jackson. After starting in Little Rock in late 1831, by 1834 Yell had moved to Fayetteville – early enough to qualify him as a founding father if not a first settler of our town. Yell was smart with his income and bought up lots of land around town, eventually owning some 900 acres of prime real estate. 500-600 of those acres were in what is now known as South Fayetteville. -

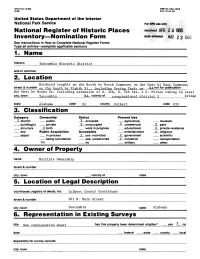

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JWR14 BBS Inventory—Nomination Form 2.3 1985 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Tuscumbia Historic District and/or common 2. Location Bordered roughly on the North by North Commons; on the East by East Commons; street & number on the south by Eighth St., including Spring Park; on -^A not for publication the West by Hooks St. including extension of W. 4th, W. 5th Sts. & S. Milton taking in steel city, town_____ Tuscumbia ___________ NA_ vicinity of congressional district 5 bridge state Alabama code 01 county Colbert code 033 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) private X unoccupied X commercial X park structure _Kboth work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment X religious object in process X yes: restricted X government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted X industrial transportation NA no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple Ownership street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Colbert County Courthouse street & number 201 N. Main Street city, town Tuscumbia state Alabama 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title See continuation sheet has this property been determined eligible? __ yes .X_ no date depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site X good ruins _JL_ altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Tuscunibia Historic District contains 639 properties that represent a diversity of residential, commercial, institutional, recreational buildings and sites associated with over 150 years of development in the city of Tuscumbia. -

Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701 May 2016 Whole Number 88 PRESERVING OUR PAST for FUTURE GENERATIONS Arkansas Statehood Day Sunday, June 12, 2016 2:00 P.M

Flashforward Published by The Washington County Historical Society 118 East Dickson Street * Fayetteville, Arkansas 72701 May 2016 Whole Number 88 PRESERVING OUR PAST FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS Arkansas Statehood Day Sunday, June 12, 2016 2:00 p.m. until 4:00 p.m. First Christian Church of Fayetteville 220 N. College Avenue • Fayetteville, AR The Hon. David Pryor will be the Statehood Day Celebraon speaker for the Washington th County Historical Associaon’s annual observance on Sunday, June 12 , in a program at the First Chrisan Church of Fayeeville. The doors will open at 1:30 p.m. with the program to begin at 2 p.m. Serving as moderator and conversaonalist with former U.S. Senator Pryor will be Kyle Kellams, News Director and Host of Ozarks At Large on KUAF, the Naonal Public Radio staon in Fayeeville. Pryor, who has served over 40 years in elected offices from Arkansas, first as a state th Representave from Ouachita County, Congressman from the 4 Congressional District, Governor of Arkansas and three terms as the U.S. Senator from Arkansas will reflect upon the history of the state. The “conversaon” will be a queson and answer exchange between Pryor and Kellams and not a formal lecture. A er the “conversaon” cookies and lemonade will be served to the membership and all guests. Parking at the church is limited so we ask those who are able to please park in the Washington County Courthouse Parking lot. Congratulations to Tony Wappel on receiving the 2016 Mayor’s Award for Outstanding Service in Historic Preservation for his book with Dennis L. -

Alabama Properties Listed on the National Register Of

ALABAMA PROPERTIES LISTED ON THE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES As of February 19, 2019 KEY: C - Contributing CC - Conditionally Contributing DOE Determination of Eligibility HABS - Historic American Buildings Survey MPS - Multiple Property Submission MRA - Multiple Resource Nomination NC Noncontributing NHL - National Historic Landmark TR - Thematic Resource Nomination Click on the county name below to go directly to beginning of each county listing in this document. Autauga Baldwin Barbour Bibb Blount Bullock Butler Calhoun Chambers Cherokee Chilton Choctaw Clarke Clay Cleburne Coffee Colbert Conecuh Coosa Covington Crenshaw Cullman Dale Dallas Dekalb Elmore Escambia Etowah Fayette Franklin Geneva Greene Hale Henry Houston Jackson Jefferson Lamar Lauderdale Lawrence Lee Limestone Lowndes Macon Madison Marengo Marion Marshall Mobile Monroe Montgomery Morgan Perry Pickens Pike Randolph Russell St. Clair Shelby Sumter Talladega Tallapoosa Tuscaloosa Walker Washington Wilcox Winston AUTAUGA COUNTY BELL HOUSE Listed: 2/12/99 550 Upper Kingston Road 1893 Structures: 4 DANIEL PRATT HISTORIC DISTRICT Listed: 8/30/84 Roughly bounded by Northington Road, 1st, 6th, Bridge, & Court Streets - Prattville 1836-1930 Structures: 224 (192 C, 32 NC) LASSITER HOMEPLACE Listed: 7/17/97 Autauga County 15, 0.5 mi North of junction of Alabama 14 and County Road 15 - Autaugaville Vicinity c. 1825 Structures: 7 (4 C, 3 NC) MONTGOMERY-JANES-WHITTAKER HOUSE Listed: 10/25/74 (Buena Vista) HABS Reynolds Mill Road, three miles South of downtown Prattville Prattville 1821-1822 Structures: 1 MOUNT SINAI SCHOOL Listed: 11/29/01 (The Rosenwald School Building Fund and Associated Buildings MPS) 1820 County Road 57 - Prattville 1919-1937, 1950 Structures: 1 Return to Page 1 This listing is intended to be used as a guide only. -

Campus Preservation Master Plan

University of Arkansas Campus Preservation Master Plan Februrary 2009 Consultant Team Aaron Ruby Susan Turner Rob Yallop Glen Bennett University of Arkansas Campus Preservation Master Plan Dale Jaeger William Shealy The information and professional opinions of Lord, Aeck & Sargent Architecture, Inc. and its subconsultants, presented in this report have been prepared for the exclusive use of the University of Arkansas and may not be relied on by third parties for any purpose without the express written permission of Lord, Aeck & Sargent Architecture, Inc. Acknowledgements Creation of the University of Arkansas Campus Preservation Master Plan was made possible through the generous support of the Getty Foundation. Recognizing the nation’s college and university campuses are repositories for significant cultural resources, the Getty Foundation developed its Campus Heritage Grants Initiative to assist institutions in preserving their historic resources. The Getty Foundation provides support to institutions and individuals throughout the world, funding a diverse range of projects that promote the understanding and conservation of the visual arts. The University of Arkansas and the project team would also like to acknowledge the following individuals and organizations for their contributions towards the success of this project. The Getty Foundation University of Arkansas Facilities Management Planning Group Vaughn Skinner, Resident Director, Arkansas Agricultural Research & Extension Center (AAREC) Ralph Wilcox and the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program staff University of Arkansas Special Collections Dr. Ethel S. Goodstein-Murphree, University of Arkansas School of Architecture Mr. Don Schaefer Mr. Jesse Mason Toms Campus Preservation Master Plan Executive Summary The University of Arkansas Preservation Master Plan was funded through within the Plan document and in a “Catalog of Resources” that provides a Getty Campus Heritage Grant awarded to the institution in 2007. -

FREE-To-SEE ALE TRAIL NORTHWEST ARKANSAS EAT! TOUR! DINING and ATTRACTIONS the RAZORBACK NIGHTLIFE GUIDE GREENWAY TRAIL TEAM and FAMILY FRIENDLY HOTELS

THE VISITOR’S GUIDE NORTHWEST TO ARKANSAS ’ TO NORTHWEST VISITOR S GUIDEARKANSAS MEET!LOCAL BAND POUR! THE AIRPLANES THE FAYETTEVILLE FREE-to-SEE ALE TRAIL NORTHWEST ARKANSAS EAT! TOUR! DINING AND ATTRACTIONS THE RAZORBACK NIGHTLIFE GUIDE GREENWAY TRAIL TEAM AND FAMILY FRIENDLY HOTELS Hampton Inn Fayeeville 479-587-8300 1-800-HAMPTON fayeevillear.hamptoninn.com Holiday Inn Express & Suites Fayeeville 479-444-6006 1-800-HOLIDAY hiexpress.com/fytvillearua Homewood Suites Fayeeville 479-442-3000 1-800-CALL HOME fayeeville.homewoodsuites.com Hilton Garden Inn Fayeeville 479-856-6040 1-888-370-0984 fayeeville.hgi.com WELCOME FAYETTEVILLE GREETING FAYETTEVILLE WE’RE GLAD YOU’RE HERE! On behalf of our team, I would like to welcome you to Fayetteville! If you are a first-time visitor, you’re in for a treat. Everywhere you look, you’ll see breathtaking scenery, a thriving art scene and fun entertainment for residents and travelers. As a business owner and long-time resident, I can’t think of any place I’d rather be than Fayetteville. I’m excited to serve on the Advertising & Promotion Commission because the city means so much to me and my family. My restaurant is one of the many eclectic eateries around town, and I’m proud to be part of this growing culinary community. I could spend all day talking about why Fayetteville is so great. But go ahead and turn the page and find out more. Better yet, explore our city in person and really see it for yourself. We look forward to showing you our home. -

Would Be Lost in the West Avenue Parking Lot at Dickson Street and West Avenue Where the Civic Plaza Is to Be Built; And

of FAYETTe u y 4RKAN' 113 West Mountain Street Fayetteville, AR 72701 479) 575- 8323 Resolution: 37- 20 File Number: 2019- 0898 SAGE PARTNERS, LLC DEPOT LOT PROPOSAL: A RESOLUTION TO AUTHORIZE MAYOR JORDAN TO SIGN LETTERS OF INTENT WITH SAGE PARTNERS, LLC, ON BEHALF OF FAYETTEVILLE DEPOT, LLC AND FARMERS & MERCHANTS BANK ( F/ K/A THE BANK OF FAYETTEVILLE), FOR THE PURCHASE OF APPROXIMATELY 0. 6 ACRES ALONG WITH NECESSARY PERMANENT ACCESS AND TEMPORARY CONSTRUCTION EASEMENTS AT THE NORTHWEST CORNER OF WEST AVENUE AND DICKSON STREET FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF A REPLACEMENT PARKING DECK FOR THE TOTAL AMOUNT OF $ 350, 000. 00, THE CONVEYANCE OF APPROXIMATELY 0. 2 ACRES AT THE NORTH END OF THE CIVIC PLAZA WHEREAS, on December 18, 2018, City Council passed resolution 250- 18 which supported using 10, 000, 000. 00 from the Cultural Arts Corridor Bond for replacement parking for the parking spaces that would be lost in the West Avenue Parking Lot at Dickson Street and West Avenue where the Civic Plaza is to be built; and WHEREAS, on Tuesday, April 9, 2019, the Citizens of Fayetteville approved Question 8 in the bond election that authorized $ 31, 685, 000 for Arts Corridor Bond Improvement which provides that, prior to the removal or loss of twenty- five ( 25) or more public parking spaces from the West Avenue Parking Lot related to the Cultural Arts Corridor, the City must replace the 290 lost parking spaces within 1000 feet of the Walton Arts Center' s west public entrance; and WHEREAS, on March 12, 2019, City staff and Garver Engineering provided an analysis of several locations within 1000 feet of the Walton Arts Center' s west public entrance that would be suitable for replacement parking. -

To Download PDF Of

Photo of Hawksbill Courtesy Arkansas Dept of Parks and Tourism ---- WELCOME ---- Welcome to the first issue of The Best of Northwest No advertiser can pay Arkansas Top 10. We are so excited to share our brand to be included in one of new magazine with you. When one of our advisory our Top 10 lists. If you board member’s asked what model we were using for would like to have us the Top 10 magazine, I enthusiastically told him that include a specific Top 10 we were using the heart model. He said he’d never list in future additions, heard of the heart model. I explained that the Top 10 please contact us via is very close to my heart as it allows us to present to our website. NWA residents, newcomers and visitors the very best of what our beautiful corner of Arkansas has to offer. We believe that our tourists, newcomers and The Top 10 is a natural and much needed off-shoot locals should all be able of our flagship publication and website, the Northwest to get in on the secret of Arkansas Travel Guide. The Northwest Arkansas the best places to eat, play, and stay in NWA. With Travel Guide, with its over sixteen hundred hospitality the Top 10 guide, you have at hand the quickest way industry listings, has been around since 2012, and to ensure that you are not disappointed whether you while it is thorough and useful, it is much like a business are dining, participating in an activity or just wanting a directory, and doesn’t offer a fast way for people to good night’s sleep. -

Washington-Willow Historic District Design Review Guidelines

WASHINGTON-WILLOW HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGN REVIEW GUIDELINES CITY OF FAYETTEVILLE, ARKANSAS 2019 “The mission of the Fayetteville Historic District Commission is to advocate for the preservation of architectural and historic resources of the city; to cultivate sense of place; to promote the use of historic architecture and the built environment for the education, enjoyment, and well-being of residents and visitors; and to encourage preservation of historic integrity in land use and development planning.” ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks are due to the many residents in the Washington-Willow Historic District who provided their time to participate in the public meetings and planning process. In addition to the residents, assistance in the preparation of this manual was provided by the City Planning Division. Particular thanks are due to the Historic District Commission for their contributions to this manual. Mayor Lioneld Jordan City Council Sonia Gutierrez, Ward 1, Position 1 Sarah Marsh, Ward 1, Position 2 Mark Kinion, Ward 2, Position 1 Matthew Petty, Ward 2, Position 2 Sloan Scroggin, Ward 3, Position 1 Sarah Bunch, Ward 3, Position 2 Teresa Turk, Ward 4, position 1 Kyle Smith, Ward 4, Position 2 Historic District Commission Angela Albright Kathryn Cook Rhianon DeLeeuw Alexandria Lee Katie Mihalevich Christine Myres David Stewart City Planning Division Staff Andrew Garner Consultant Thomason and Associates, Preservation Planners, Nashville, Tennessee 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 - Introduction and Purpose of This Manual…..……………..................1 -

Historic Hike of Fayetteville Map

1/ Old Main 7/ Trail of Tears Memorial was designed by Arkansas architect Charles L. Thompson. The courthouse was added to Old Main was built as the first permanent academic building of the University of When members of the eastern Indian nations were forced from their traditional the National Register of Historic Places in 1972, and the jail was added in 1978. Arkansas, originally known as the Arkansas Industrial University. It was built from 1873 homelands in the American southeast and moved west to the Indian Territory, to 1875 and designed in the Second Empire style by architect John Mill van Osdel, based present-day Oklahoma, the path of some of the Cherokee bands came through 12/ Headquarters House Museum on his design for a similar building at the University of Illinois. Today, the dean’s offices Fayetteville during 1838 and 1839. Most of them came southwest from Pea Ridge, & Archibald Yell Law Office of the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences are housed in the building as well passing through the Mount Comfort community and then turning west. John Benge led Headquarters House was built in 1853 for the Jonas and Matilda Tebbetts family. During as several academic departments. Many of the university’s guest speakers appear in a detachment that passed through the south side of Fayetteville and camped near the the Civil War, the Tebbetts left Fayetteville for the safety of the north, and both the Giffels Auditorium on the second floor. The Clock Tower on the southeast corner did not present campus of Fayetteville High School.