Campus Preservation Master Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes.Form

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS BOARD OF TRUSTEES ARKANSAS SCHOOL FOR MATHEMATICS, SCIENCES AND THE ARTS CREATIVITY AND INNOVATION COMPLEX, SECOND FLOOR OAKLAWN FOUNDATION COMMUNITY CENTER HOT SPRINGS, ARKANSAS 1:30 P.M. MARCH 27, 2019 AND 8:30 A.M. MARCH 28, 2019 TRUSTEES PRESENT: Chairman John Goodson; Trustees Mark Waldrip; Stephen A. Broughton, MD; Charles “Cliff” Gibson III; Morril Harriman; Sheffield Nelson; Kelly Eichler; Tommy Boyer; Steve Cox and Ed Fryar, PhD. UNIVERSITY ADMINISTRATORS AND OTHERS PRESENT: System Administration: President Donald R. Bobbitt; General Counsel JoAnn Maxey; Vice President for Agriculture Mark J. Cochran; Vice President for Academic Affairs Michael K. Moore; Vice President for University Relations Melissa Rust; Chief Financial Officer Gina Terry; Associate Vice President for Finance Chaundra Hall; Associate Vice President for Benefits & Risk Management Services Steve Wood; Senior Director of Policy and Public Affairs Ben Beaumont; Director of Communications Nate Hinkel; Chief Audit Executive Jacob Flournoy; Chief Information Officer Steven Fulkerson; Assistant to the President Angela Hudson and Associate for Administration Sylvia White. UAF Representatives: Chancellor Joseph E. Steinmetz, Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs Jim Coleman, Vice Chancellor for Finance and Administration Chris McCoy, Vice Chancellor for Intercollegiate Athletics Hunter Yurachek, Senior Associate Athletic Director of Business Operations/CFO Clayton Hamilton and Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Charles Robinson. Board of Trustees Meeting March 27 and 28, 2019 Page 2 UAMS Representatives: Chancellor Cam Patterson; Senior Vice Chancellor for Clinical Programs and Chief Executive Officer, UAMS Medical Center, Richard Turnage; Vice Chancellor and Chief Financial Officer Amanda George; Vice Chancellor for Institutional Support Services and Chief Operating Officer Christina Clark and Associate Vice Chancellor, Campus Operations Brian Cotton. -

Arkansas Soccer Media Guide, 2007

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Arkansas Soccer Athletics 2007 Arkansas Soccer Media Guide, 2007 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Women's Athletics Department. Women's Communications Office University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Women's Athletics Department. Women's Sports Information Office Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/soccer Citation University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations., University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Women's Athletics Department. Women's Communications Office., & University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Women's Athletics Department. Women's Sports Information Office. (2007). Arkansas Soccer Media Guide, 2007. Arkansas Soccer. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/soccer/3 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Soccer by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fayetteville, Arkansas One of America’s Best Places to Live The rolling hills of the Ozark Mountain foothills has long been a place for people young and old to unwind and relax, but it wasn’t un- til recently that the secret which is Northwest Arkansas reached the public. Now the region which begins in Fayetteville and stretches up to Bentonville is widely considered one of the best places to live and here are a few examples why. Arkansas Quick -

2014 UA Consolidated Financial Statement

UAThe University of ArkansasM at Monticello Monticello • Crossett • McGehee UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS SYSTEM Consolidated Financial Statements FY2013-14 BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jim von Gremp, Chairman Ben Hyneman, Vice Chairman airman Jane Rogers, Secretary Dr. Stephen A. Broughton, Asst. Secretary Reynie Rutledge David Pryor Mark Waldrip John C. Goodson Mrs. Jane Rogers, Board Chairman Charles “Cliff” Gibson, III Jim von Gremp, Chairman Morril Harriman ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICERS Donald R. Bobbitt President Michael K. Moore Vice President for Academic Affairs Daniel E. Ferritor Vice President for Learning Technologies Barbara A. Goswick Vice President for Finance & CFO Ann Kemp Vice President for Administration Melissa K. Rust Vice President for University Relations Fred H. Harrison \ General Counsel Dr. Donald R. Bobbitt, President Table of Contents Board of Trustees & Administrative Officers .................................................................................... Inside Front Cover Letter of Transmittal ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Independent Auditor’s Report ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Management Discussion & Analysis ............................................................................................................................. 6 Five Year Summary of Key Financial Data ................................................................................................................ -

Vol Walker Hall + the Steven L Anderson Design Center

VOL WALKER HALL + THE STEVEN L ANDERSON DESIGN CENTER THE ADDITION AND RENOVATION TO VOL WALKER HALL AT THE FAY JONES SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE IS A COMPLEX BUT RESOLUTE HYBRID OF A BEAUTIFULLY RESTORED HISTORICAL BUILDING, AND A MODERN COMPLEMENT. Vol Walker Hall + The Steven L. Anderson Design Center The Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design at the University of Arkansas is a striking and effective hybrid of a beautifully restored and renovated historical building, Vol Walker Hall (65,000 SF), and a contemporary insertion and addition, the Steven L. Anderson Design Center (37,000 SF). The ensemble invigorates the historical center of the campus and instills new life in Vol Walker Hall, the campus’s original library and home to the School of Architecture since 1968. The overall design is a didactic model, establishing a tangible discourse between the past and present while providing state of the art facilities for 21st century architectural and design education while achieving LEED Gold in recognition of the sustainable and urban strategies employed. The Anderson Design Center is a modern complement to the neo-classical architecture of Vol Walker Hall, sensitive to the past and conceived to enhance the spatial character of the historic campus plan. The footprint of the addition mirrors that of the traditional structure’s primary east wing, physically and conceptually balancing the old and the new. The Design Center’s contemporary vocabulary resonates with its neighbor’s design through similar materials and proportions. Regulating lines established by Vol Walker Hall’s classical composition and proportions of string courses, cornice lines, fenestration and moldings generated the organizational system for the elevations of the Anderson Design Center. -

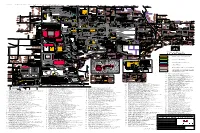

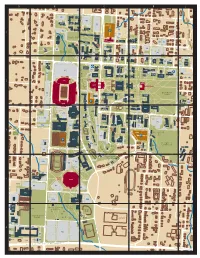

Building Index Legend

DWG LOCATION -- *:\ACADDWGS\CAMPUS\CAMPUS\zCAMP-12( MASTER CAMPUS MAP )\CAMP-12.DWG CLEVELAND ST 123B 123 151 123A 100 80 79 134C GARLAND AVE 134A 134 110 167 101 67 134B DOUGLAS ST 178 DOUGLAS ST 112 174 78 12 182 STORER ST OAKLAND AVE LINDELL AVE LEVERETT ST WHITHAM AVE 98 11 68 97 156 137 115 41 49 168 50 13 142 184 126 114 MAPLE ST MAPLE ST 93 119 7 16 158 10 144 129 108 62 138 2 6 90 72 119A 102 9 REAGAN ST RAZORBACK RD 76 55 172 15 48 135 LAFAYETTE ST 177 71 54 53 39 136 60 170 82 38 152 60A 73 ARKANSAS AVE 30 GARLAND AVE 121 163 WEST AVE 84 47 113 143 22 42 96 153 85 MARKAM RD DICKSON ST DICKSON ST 18 141 91 128 35 124 26 157 109 46 130 75 74 117 61 173 43 116 28 34 139 STADIUM DR STADIUM 86 23 103 176 WILLIAMS ST 179 HARMON AVE HOTZ DR 180 57 57A McILROY AVE 92 31 57B 161 181 92A UNIVERSITY AVE DUNCAN AVE 57E 127 52 57C WALTON ST 94 27 118 164 175D 166 FAIRVIEW ST 175E 155 164A 125 57D 175C 166A MEADOW ST 58 175 14 44 165 LEGEND 140 CENTER ST 25 5 175B CENTER ST 111 UNIVERSITY BUILDINGS 145 184 GREEK HOUSING 185 186 120 8 29 UNIVERSITY HOUSING 63 NETTLESHIP ST VIRGINIA ST ATHLETICS 162 64 x x x x x x x 19 x x x x x x LEROY POND RD x x x x x x x x 149 51 147 21 NON UNIVERSITY BUILDINGS 95 20 105 150 PROPOSED NEW BUILDINGS EASTERN AVE 65 131 OR EXIST BUILDINGS UNDER 99 59 24A CONSTRUCTION 36 RAZORBACK RD 24 107 122 1 66 106 163. -

2021–2022 University of New Orleans New Student and Family Guide

2021–2022 Parent & Family GUIDE About This Guide CollegiateParent has published this guide in partnership with the University of Arkansas. Our goal is to share helpful, timely information about your student’s college experience and to connect you to relevant campus and community resources. Please refer to the school’s website and contact information below for updates to information in the guide or with questions about its contents. CollegiateParent is not responsible for omissions or errors. This publication was made possible by the businesses and professionals contained within it. The presence of university/ college logos and marks in the guide does not mean that the publisher or school endorses the products or services offered by the advertisers. CollegiateParent is committed to improving the accessibility of our content. When possible, digital guides are designed to meet the PDF/UA standard and Level AA conformance to WCAG 2.1. CollegiateParent Unfortunately, advertisements, campus- 3180 Sterling Circle, Suite 200 provided maps, and other third-party Boulder, CO 80301 content may not always be entirely Advertising Inquiries accessible. If you experience issues with Л (866) 721-1357 the accessibility of this guide, please reach î CollegiateParent.com/advertisers out to [email protected]. ©2021 CollegiateParent. All rights reserved. Design by Kade O’Connor Л (479) 575-5002 Л (855) 264-0001 (Toll Free) ƍ [email protected] For more information, please contact: î family.uark.edu University of Arkansas î uark.campusesp.com New Student & Family Programs – Razorback Family Portal ARKU A688 \ facebook.com/RazorbackParent 1 University of Arkansas H instagram.com/RazorbackParent CONTENTS Welcome to the Razorback Family! ............................... -

University of Arkansas Parking Rules

1 2 3 4 5 6 University of Arkansas Transit and Parking web site: Parking Map http://parking.uark.edu Map is not drawn to scale. Map last updated July 26, 2017. Subject to change at any time. To Agricultural Research Lot sign designation takes precedence over map designation. Extension Center Changes may have occurred since the last update. For parking information regarding athletic or special events, Legend please visit the Transit and Parking website or call 40A (479) 575-7275 (PARK). Reserved Hall Ave. Faculty/Staff Cleveland St. Resident Reserved (9 months) 41 UUFF Student 40 MHWR MHER ve. A ve. Remote UAPD ve. 37 A Sub A REID Station Parking Meters GAPG Garland GACS A HOTZ Leverett Ave. Lindell Short-term Meters 42 Oakland MHSR 36B A Patient 75 Parking Parking Garage (Metered Parking Available) GACR NWQC 36 Storer Ave. RFCS Taylor St. Under Construction STAQ NWQB JTCD 42 BKST HOUS CAAC 35N 31N ADA Parking Cardwell Ln. ECHP NWQD Loading Zones NWQA Douglas St. Douglas St. 28 FUTR 36A 30 39 35 78 78A Motorcycle Parking Razorback Rd. 31 ve. ADPS A ve. POSC STAB A ZTAS Scooter Parking FWLR 43 38 66 Ave. Gregg HOLC CIOS Research Oliver Lab Parking 27 AFLS Whitham 29 HLTH MART 34 Reserved Scooter Parking ABCM PDCM 10 VS UNHS DDDS KKGS A FWCS D AOPS B 1 68 PBPS Maple St. Maple St. SCHF KDLS Night Reserved Maple St. B WATR ROSE PTSC ARMY Inn at Carnall Hall 14 ALUM ADMN & Ellas Restaurant Parking Parking Admin. 14D HUNT 9 MEMH No Overnight (See list below) 44 26 ARKA 7 CARN Parking Registrar AGRX 14A 1 PEAH ’ 31N 8 SCSW GRAD FIOR 14C FPAC HOEC AGRI 2 47N 76 14B Reagan St. -

Addendum-2 Brief History of Arkansas Academy of Science Dr

Addendum-2 Brief History of Arkansas Academy of Science Dr. Collis Geren AAS Historian-As reported to the AAS business meeting for April 1st, 2016 From the Arkansas Academy’s Home Page: History The Arkansas Academy of Science began meeting in 1917 as a group of scientists wishing to establish regular avenues of communication with one another and promote science and the dissemination of scientific information in the state. Over the years since, the Academy has been led by scientists of notable accomplishment, such as Dwight Moore, Ruth Armstrong, C. E. Hoffman, Jewel Moore, Joe Nix, Ed Dale, to name a few. The Academy is a non-partisan, non-political, professional organization consisting of scientists who pay dues to join with other scientists to promote science in the state and region. The specific areas of science included (but not limited to) are Biomedical, Botany, Plant Science, Chemistry, Physics, Astronomy, Engineering, Geology, Environmental Science, Ecology, Invertebrate Zoology, and Vertebrate Zoology. An Executive Committee, consisting of a President, Past-President, President-Elect, Vice President, Secretary, Treasurer, Journal Editors and Newsletter Editor convenes twice annually to discuss issues and determine some policy and procedures for maintaining and operating the Academy. The chairpersons of standing committees and the President of the Arkansas Science Teachers Association are invited to meet with the Executive Committee. The Academy holds an annual meeting the second weekend in April during which business is transacted and reports/papers on research and teaching methods are given. The meeting provides many opportunities for colleagues to visit and share information about their respective work. -

Arkansas Men's Track & Field Media Guide, 2012

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Arkansas Men's Track and Field Athletics 2012 Arkansas Men's Track & Field Media Guide, 2012 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/track-field-men Citation University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations. (2012). Arkansas Men's Track & Field Media Guide, 2012. Arkansas Men's Track and Field. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/track- field-men/4 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Men's Track and Field by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2011 SEC OUTDOOR CHAMPIONS Index 1-4 History and Records 49-84 Table of Contents 1 Razorback Olympians 50-51 Media Information 2 Cross Country Results and Records 52-54 Team Quick Facts 3 Indoor Results and Records 55-61 The Southeastern Conference 4 Outdoor Results and Records 62-70 Razorback All-Americans 71-75 2011 Review 5-10 Randal Tyson Track Center 76 2011 Indoor Notes 6-7 John McDonnell Field 77 2011 Outdoor Notes 8-9 Facility Records 78 2011 Top Times and Honors 10 John McDonnell 79 Two-Sport Student Athletes 80 2012 Preview 11-14 Razorback All-Time Lettermen 81-84 2012 Outlook 12-13 2012 Roster 14 The Razorbacks 15-40 Returners 16-35 Credits Newcomers 36-40 The 2012 University of Arkansas Razorback men’s track and fi eld media guide was designed by assistant The Staff 41-48 media relations director Zach Lawson with writting Chris Bucknam 42-43 assistance from Molly O’Mara and Chelcey Lowery. -

BOARD of TRUSTEES Meeting Agenda

UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS BOARD OF TRUSTEES Meeting Agenda March 28-29, 2018 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff University of Arkansas at Little Rock University of Arkansas at Monticello University of Arkansas at Fort Smith University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture Phillips Community College of the University of Arkansas University of Arkansas Community College at Hope University of Arkansas Community College at Batesville University of Arkansas Community College at Morrilton Cossatot Community College of the University of Arkansas University of Arkansas – Pulaski Technical College University of Arkansas Community College at Rich Mountain Arkansas Archeological Survey Criminal Justice Institute Arkansas School for Mathematics, Sciences, and the Arts University of Arkansas Clinton School of Public Service University of Arkansas System eVersity MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS JOHN F. GIBSON UNIVERSITY CENTER GREENROOM UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS AT MONTICELLO MONTICELLO, ARKANSAS MARCH 28-29, 2018 TENTATIVE SCHEDULE: Wednesday, March 28, 2018 - UAM Gibson University Center, Green Room 11 :00 a.m. Tour of Campus for Board Members 12:00 p.m. Lunch for Board Members -House Room (12:30 p.m. Heavy hors d'oeuvres available for all other meeting attendees in Capitol Room) 1:00 p.m. Chair Opens Regular Session 1:00 p.m.* Athletics Committee Meeting 1:45 p.m.* Joint Hospital Committee Meeting 2:15 p.m.* Joint Hospital and Audit and Fiscal Responsibility Committees Combined Meeting 3:15 p.m.* Audit and Fiscal Responsibility Committee Meeting 3:45 p.m.* Buildings and Grounds Committee Meeting 4:15 p.m.* Academic and Student Affairs Committee Meeting 6:00 p.m. -

2007-08 Media Guide.Pdf

07 // 07//08 Razorback 08 07//08 ARKANSAS Basketball ARKANSAS RAZORBACKS SCHEDULE RAZORBACKS Date Opponent TV Location Time BASKETBALL MEDIA GUIDE Friday, Oct. 26 Red-White Game Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. Friday, Nov. 2 West Florida (exh) Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. michael Tuesday, Nov. 6 Campbellsville (exh) Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. washington Friday, Nov. 9 Wofford Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. Thur-Sun, Nov. 15-18 O’Reilly ESPNU Puerto Rico Tip-Off San Juan, Puerto Rico TBA (Arkansas, College of Charleston, Houston, Marist, Miami, Providence, Temple, Virginia Commonwealth) Thursday, Nov. 15 College of Charleston ESPNU San Juan, Puerto Rico 4 p.m. Friday, Nov. 16 Providence or Temple ESPNU San Juan, Puerto Rico 4:30 or 7 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 18 TBA ESPNU/2 San Juan, Puerto Rico TBA Saturday, Nov. 24 Delaware St. Fayetteville, Ark. 2:05 p.m. Wednesday, Nov. 28 Missouri ARSN Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. Saturday, Dec. 1 Oral Roberts Fayetteville, Ark. 2:05 p.m. Monday, Dec. 3 Missouri St. FSN Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. Wednesday, Dec. 12 Texas-San Antonio ARSN Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. Saturday, Dec. 15 at Oklahoma ESPN2 Norman, Okla. 2 p.m. Wednesday, Dec. 19 Northwestern St. ARSN Fayetteville, Ark. 7:05 p.m. Saturday, Dec. 22 #vs. Appalachian St. ARSN North Little Rock, Ark. 2:05 p.m. Saturday, Dec. 29 Louisiana-Monroe ARSN Fayetteville, Ark. 2:05 p.m. Saturday, Jan. 5 &vs. Baylor ARSN Dallas, Texas 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Jan. -

Campusmap.Pdf

A B C D E 40a C L E V E L A N D S T R E E T 41 MHER C L E V E L A N D S T R E E T 40 REID MHWR 37 GARC l i HOTZ a MHSR 75 r 42 T 1 OLIVER AVENUE k 75 e RAZORBACK ROAD NWQC Wilson Park e LINDELL AVENUE 36 r NWQB OAKLAND AVENUE STORER AVENUE Maple Hill 79 C LEVERETT AVENUE BKST Rose l WHITHAM AVENUE ECHP l HOUS JTCD HRDR Hill 35 31 u c D O U G L A S S T R E E T S POSC 28 30 FUTR 36a GARLAND AVENUE 39 43 GTWR 78 78a FWLR Maple Hill HOLR Arboretum 29 ADPS 38 27 AFLS 66 12 STAB 1 HLTH ZTAS CIOS 32 DAVH UNHS DDDS KKGS 34 M A P L E S T R E E T PHMS ACOS 33 AOPS WILSON AVENUE SCHF GREGG AVENUE Sorority Row 10 PARK AVENUE M A P L E S T R E E T ALUM KDLS ADMN ROSE PBPS O HUNT a 26 PTSC ARMY M A P L E S T R E E T 9 AGRX MEMH 44 k 7 R CARN 76 i d 8 PEAH ARKA 25 FPAC LLAW SCSW 2 g WATR HOEC AGRI GRAD e 14b 14c A Arkansas r 2 FBAC b Union o r e CAMPUSMAIN WALK t ARKU Central u MULN WALK m Quad Old Main L A F A Y E T T E S T R E E T Reynolds 72 Stadium Historic Old Main MUSC FNAR CHEM Core Lawn FARM WEST UNST OZAR SDPG 53 CHBC WAHR DISC ARKANSAS AVENUE BAND 4 5 STON 15a RAZS 45 FERR PKAF 6 GIBX COGT 22 ENGR GREGG AVENUE M A R K H A M R O A D GIBS Greek HILL SCEN BELL Theatre GREG MARK JBAR 67 O D I C K S O N S T R E E T a 11 k PHYS SINF FSBC MEEG 73 R CHPN i d D I C K S O N S T R E E T g JBHT e SUST 18 48 FNDR E 71 RAZORBACK ROAD PDTF U Walton KIMP N NANO KASF 73a FSFC 59 50 E 20 19 Arts H O T Z D R I V E BLCA HUMP V Center A W I L L I A M S T R E E T GLAD 3 N 48a YOCM WJWH O M Hotz STADIUM DRIVE HAPG Evergreen R Park MCILROY AVENUE A H Hill 50 WCOB