Stable and Secure?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 2 the PROJECT 2.0 the Project 2.1 Project Road Alignment

Kaladan Multimodal Transport Project in Mizoram EIA-EMP Report Construction of road from NH-54 to Indo-Myanmar border Chapter-2- The Project CHAPTER 2 THE PROJECT 2.0 The Project 2.1 Project road alignment The Project Road takes off at 76.400 km on NH-54 at Lawngtlai town in south Mizoram, runs towards the south and terminates at Indo Myanmar border ( River Zocha) road. The Project road alignment passes through frequently cultivated degraded jhumland. It crosses the existing BRO roads, namely, Lawngtlai to Diltlang Parva road at one point and Nalkawn Chamdur Valley road at four points. The road, proposed to be of double – lane NH standard is of length 99.830 km. The road also passes through the villages of Saizawh East and Zochachhuah. The location of this proposed trade route has been shown in Map 2.1 . About 17.88 % length of the road passes through private land , 75.76% passes through degraded jhumland and 6.36 % pass through forest land. The road passes through mainly two villages ,viz Saizawh East and Zochachhuah. 2.2 Proposed Road Segments The road has been divided into four homogeneous segments I, II, III and IV with respect to physical features as given in following table Table2.1: Project road segments Location in chainages Type of Terrain Major River crossing Length Segment Name of Location From To (km) Hilly Steep River at km Lawngtlai Leichhekawn Segment-I (0.00) (40.980) 40.980 4.098 36.882 Ruankhum 34.634 Leichhekawn R.Ngengpui Segment-II (40.980) (56.500) 15.520 9.1568 6.3632 Ngengpui 56.500 Darnam R.Ngengpui Saddle Segment-III -

Executive Summary

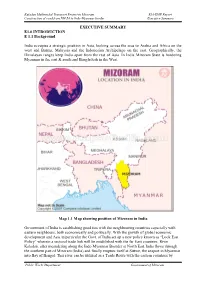

Kaladan Multimodal Transport Project in Mizoram EIA-EMP Report Construction of road from NH-54 to Indo-Myanmar border Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY E1.0 INTRODUCTION E 1.1 Background India occupies a strategic position in Asia, looking across the seas to Arabia and Africa on the west and Burma, Malaysia and the Indonesian Archipelago on the east. Geographically, the Himalayan ranges keep India apart from the rest of Asia. In India Mizoram State is bordering Myanmar in the east & south and Bangladesh in the West. Map 1.1 Map showing position of Mizoram in India Government of India is establishing good ties with the neighbouring countries especially with eastern neighbours, both economically and politically. With the growth of global economic development and Asia in particular the Govt. of India set up a new policy known as “Look East Policy” wherein a sectoral trade link will be established with the far East countries. River Kaladan, after meandering along the Indo Myanmar Boarder at North East India flows through the southern part of Mizoram (India) and finally empties itself at Sittwe, the seaport in Myanmar into Bay of Bengal. This river can be utilized as a Trade Route with the eastern countries by Public Works Department Government of Mizoram Kaladan Multimodal Transport Project in Mizoram EIA-EMP Report Construction of road from NH-54 to Indo-Myanmar border Executive Summary Inland waterway up to the navigable point and by road transport where navigation is not feasible. Then the goods to imported can be distributed in other parts of the country especially among north eastern states by road or train .So the means of transport comprises of sea, inland water, roads & railways and land will serve as a Multi-Modal trade route. -

The Mizoram Gazette Published by Authority

Regd. No. NE 907 • The Mizoram Gazette Published by Authority VOL. xxv Aizawl Friday, 1. 11. 1996 Kartika 10, S.E. 1918 Issue No. 44 Government of Mizoram Part I Appointments, Postings, Transfers, Powers, Leave and Other Personal Notioes and Order&. • (ORDERS BY THE GOVERNOR) I • ! • NOTIFICATIO NS • No. A. 19015j1� 196-VIG the 1st November, 1996. On the expiry of his re-employ ment as Deputy Superintendent of Police, Anti-Corruption Branch for period of 4 (four) months with effect from 1.7.1996 to 31.10 1996, Pu R. Doliana, Deputy Superintendent of Police, Anti-Corruption Branch is released from the office of Superintendent of Police, Anti-Corruption Branch on 31.10.96(AjN). T. Sangkunga, Deputy Secretary to the Govt. of Mizoram, Vigilance Department. No. A. 33012jlj96-HFW(L) the 28th October, 1996. The Governor of Mizoram is pleased to retire and release Pi Thanpari Pautu, Dy. Director (Nursing), Mizoram Aizawl who bas attained the age of superannuation retirement with effect from 31. 10. 1996 (A N)' She wiIl hand over charge to Director, Health & Family Welfare Department. Haukhum Hauzel, Commisioner to the Govt. of Mizoram, Health & Family Welfare Department. \ 2 No. A.l1 013/1/94-EDN(L): the 31st October, 1996. In the interest of Public Service, the Governor of Mizoram is pleased to order tr:J.n<;f�r and posting of the fo llowing Lecturers to the Colleges shown against their nam�s with immediate effect. 51. Name of Lectura Present place New place Remarks No. of posting of posting I 2 3 4 5 • Pu T. -

Pab) 2O1a-19, Hetd on 25.5,2018 - Circulation of Minutes in Respect of L{Izoram

F. No. 20 5/2018-15.17 Governrnent of India Ivlinistry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education & Uteracy Oated the 13s August, 2018 Ssbiect: Samagra Shiksha -Meeting of the project Approval Board (pAB) 2O1a-19, hetd on 25.5,2018 - Circulation of Minutes in respect of l{izoram. The meeting of the Project Approvat Board of Samagra Shikha was held on 25.5.2018 in Conference Room No.220-A Wing, Department of Fertilizers, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi to consider and approve the Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B), 2018-19 for the State of l\4izoram. 2. A copy of the PAB minutes duty approved by the Secretary(SE&L) in respect of A 2018 19 for the State of l4izoram under Samagra Shiksha ls enclosed. Under Secretary to Tel Email: sbhushan To 1. Shri Rakesh Srivastava, Secretary, tyinistry of W & C.D. 2. Smt. t4. Sathiyavathy, Secretary, I4inistry of Labour & Emptoyment. 3. l4s. G. Latha Krishna Rao, Secretary, I\4 n stry of Social Justice & Empowerment 4. Iqs. Leena Nair, Secretary, ltinistry of TrjbalAffairs 5. Stlri Parameswarao lyer, kretary, ltinistry of Drinking Water & Sanitatio!, 4th floor, paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New De|hi,110003. 6. Shri Ameising Luikham, Secretary, 14 nistry of Minority Affairs, 11th floor, paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003. 7. Ms. G. Latha Krishna Rao, Secretary, Department of Disability Affairs, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi - 11OOO3. 8. Ms. Poonam Srivastava, Dy. Adviser (Education), Niti Aayog. 9. Prof. Hrushikesh Senapaty, Director, NCERT. 10. -

The Mizoram Gazette

The Mizoram Gazette EXTRA ORDINARY Published by Authority Regn. No. NE-313(MZ) Rs.2/- per Issue VOL-XXXIV Aizawl, Monday, 17.10 .2005 Asvina25, S.E. 1927, Issue No.274 NOTICE OF PUBLICATION OF LIST OF POLLING STATIONS No.H.I4012/S/2005- DC(LTI), the 1 st September,2005. In pursuance of the provisions of Rule159 (1 ) of "The Lai Autonomous District Council (Constitution and Conduct of Business) Rules,2002 , I, Johny T. O. Returning Officer for General Election to Lai Autonomous District Council-2005hereby provide for 1-23 MDCConstituencies, the list of polling stations specified in the appended list for the . polling areas or groups of voters noted against each. Sd/ JohnyT.O. ReturningOfficer 1-23 MDC Constituencies LaiAutonomous DistrictCouncil LawngtlaiDistrict : Lawngtlai � A r 2 Ex-27412005 AI}PENDIX : LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR GENERAL ELECTION TO LAI AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL - 2005 '10. & Name of MDC No. & Name of Polling Building in which it will Whether for all voters or Polling Areas Constituency Station be located men only or women only t 2 3 4 5 t) 111 - Pangkhua Govt. Middle School, Pangkhua Pangkhua For all voters 1 - PANGKHlJA 112 - Cheural Govt. Middle School, Cheural 1) Cheural -do- 2/1 - Sangau-I 1) Sangau -I -do- 2 - SANGAU EAST Primary School- I, Sangau-I 2) Sentetfiang 2/2 - Thaltlang Middle School, Thaltlang 1) Thaltlang -do - - 1) Sangau - II 311 -Sangau -II Govt. Middle School, Sangau-II -do - - 2) Part of Sam!au I - 3 - SANGAU WEST 311 (A) - Sangau -II 1) Sangau. II Govt. Middle School, Sangau-II -do - u Auxiliary 2) Part of Sanga • I 4/1 -Lungtian Middle School, Lungtian 1)Lungtia n -do- 4 - LUNGTIAN 4/2 - Vartek Primary School, Vartek 1) Vartek -do- 4/3 - Vartekkai Primary School, Vartekkai 1) Vartekkai -do- 5/1 - Lungpher Govt. -

3669 Ha Project Cost

0 AREA : 3669 Ha Project Cost : 550.35 Lakhs Hmawngbuchhuah, Kakichhuah, Sabualtlang. Prepared by, DO, Soil & Water Conservation Deptt. 1 INDEX CHAPTER Page No. 1. Introduction ------------------------------------------3 2. Project Profile ------------------------------------------8 3. Basic Information of Project Villages ------------------------------------------13 4. Participatory Rural Appraisal ------------------------------------------14 5. Problem Typology ------------------------------------------15 6. Project Intervention Plan ------------------------------------------18 7. DPR Plan Abstract ------------------------------------------19 8. Preparatory Phase. ------------------------------------------20 9. Work Plan Details ------------------------------------------21 10. Consolidation and Withdrawal Phase. ----------------------------------23 11. Capacity Building Institute Identified ----------------------------------24 12. Institutional & Capacity building Plan ----------------------------------25 13. Basic Profile of the project location -------- -------------------------27 14. Maps of the project ----------------------------------28 15. Institutional mechanism& Agreements. ----------------------------------32 16. SWOT Analysis of PIA. ----------------------------------33 17. PIA & Watershed Committee details. ----------------------------------34 18. Convergence Plans. ----------------------------------35 19. Expected Outcomes. ----------------------------------37 20. Expected Estimate Outcomes. ----------------------------------39 -

F. No. Msdp-13/176/2017-Msdp-MOMA Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11Th Floor, Pt Deen Dayal Antodaya Bhavan C.G.O

F. No. MsDP-13/176/2017-MsDP-MOMA Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11th Floor, Pt Deen Dayal Antodaya Bhavan C.G.O. Complex, Lodi Road NewDelhi-110003 Dated: 27.09.2017 To, The Pay & Accounts Officer, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Paryavaran Bhavan, New Delhi Subject: Grant in aid under the Centrally Sponsored Scheme of Multi sectoral Development Programme for Minority Concentration District to Government of Mizoram for the year 2017-18 for Lawngtlai District. Sir, In continuation to this Ministry's sanction letter of even number dated 29.02.2016, I am directed to convey the sanction of the President for release of an amount of Rs 2, 91, 11,000/- (Rupees Two Crore Ninety-One Lakh Eleven Thousand Only) as 2nd instalment to the Govt. of Mizoram for implementing the scheme "Multi Sectoral Development Programme for Minority Concentration Districts" for Lawngtlai district as per the details enclosed at Annexure -I. The non-recurring grant may be released to the Govt. of Mizoramthrough CAS, Reserve Bank of India, Nagpur. 2. The State Government should ensure that proportionate share of State share for the projects mentioned at Annexure-I is released to the implementing agency along with Central share. 3. The expenditure is debitable to Demand No.66, Ministry of Minority Affairs Major Head- "3601" Grant-in-aid to State Governments, 06- Grants for State Plan Schemes (Sub Major Head), 101-General-(Welfare of Schedule Casts/Schedule Tribes and Other Backward Classes and Minorities) -Other Grants (Minor Head), 49 - Multi sectoral Development Programme for minorities, 49.00.35 - Grant for creation of capital assets for the year 2017-18. -

1 List of Health Insitution Including Hospital/Private

LIST OF HEALTH INSITUTION INCLUDING HOSPITAL/PRIVATE HOSPITAL/SUB-DISTRICT HOSPITAL/CHC/PHC/MAIN CENTRE/SUB-CENTRE AND CLINICS AIZAWL WEST DISTRICT HOSPITAL/PRIVATE PHC/UPHC MAIN CENTRE SUB-CENTRE SUB-CENTRE CLINICS CLINICS COVERED HOSPITAL/SUB- COV ERED VILLAGES VILLAGES DISTRICT HOSPITAL/ CHC HOSPITAL UPHC under 1) Aizawl S M/C 1) Republic S/C Republic 1) ITI Clinic ITI 1. Referral Hospital, NUHM 2) Upper Republic S/C Upper Republic 2) Tuikhuahtlang Clinic Tuikhuahtlang Falkawn 1. Chawlhhmun 3) Mission Veng S/C Mission Vengthlang 3) Republic Vengthlang Republic Vengthlang 2. Dist. TB Centre, 2. Hlimen 4) Kulikawn S/C Kulikawn 4) Thakthing Clinic Thakthing Aizawl Dist., 3. Lawipu 5) Venghnuai S/C Venghnuai 5) Model Veng Clinic Model Veng Falkawn 6) Salem S/C Salem Veng 6) Mission Veng Clinic Mission Veng 7) Tlangnuam S/C Tlangnuam 7) S. Hlimen Clinic S. Hlimen SUB-DISTICT Tlangnuam Vengthar 8) Samtlang Clinic Samtlang HOSPITAL 8) Melthum S/C Melthum 9) Lungleng Clinic Lungleng 1. Kulikawn Hospital Saikhamakawn 10) Damveng Clinic Damveng 9) Lungleng S/C Lungleng PRIVATE HOSPITAL 10) Hualngohmun S/C Hualngohmun 1. Aizawl Hospital, 11) Melriat S/C Melriat Khatla 2) Aizawl West 1) Zotlang S/C Zotlang 1) Kanan Clinic Kanan 2. BN Hospital, M/C 2) Vaivakawn S/C Vaivakawn 2)Rangvamual Clinic Rangvamual Kulikawn 3) Hunthar S/C Hunthar Phunchawng 3. Alpha Hospital, Kulikawn 4) Tanhril Tanhril 3) Bungkawn Vengthar Bungkawn Vengthar 4. Seventh Day Tuivamit 4) Lawipu Clinic Lawipu Hospital, Vaivakawn 5) Sakawrtuichhun S/C Sakawrtuichhun 5) Dinthar -

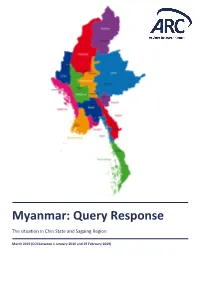

Myanmar: Query Response

Myanmar: Query Response The situation in Chin State and Sagaing Region March 2019 (COI between 1 January 2016 and 19 February 2019) Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. © Asylum Research Centre, 2019 ARC publications are covered by the Creative Commons License allowing for limited use of ARC publications provided the work is properly credited to ARC, it is for non-commercial use and it is not used for derivative works. ARC does not hold the copyright to the content of third party material included in this report. Reproduction or any use of the images/maps/infographics included in this report is prohibited and permission must be sought directly from the copyright holder(s). Please direct any comments to [email protected] Cover photo: © Volina/shutterstock.com 2 Contents Explanatory Note ............................................................................................................................ 7 Sources and databases consulted ................................................................................................. 13 List of acronyms ............................................................................................................................ 17 Map of Myanmar .......................................................................................................................... 18 Map of Chin State ........................................................................................................................ -

Globalization and Connectivity in Mizoram

Vol. VI, Issue 2 (December 2020) http://www.mzuhssjournal.in/ Globalization and Connectivity in Mizoram T. Lianhmingsanga * Abstract The process of globalization has resulted in the improvement of infrastructure and transportation and communication, international trade, and business. Along with globalization in Mizoram, the Act East Policy will play a significant role in the development of the state and it will gain many benefits as it will be the corridor for Southeast Asia and central India. Many routes in terms of aviation, by-roads, and of course railways within Mizoram state will lie in a great strategic point for India. Also, the coming up of globalization in the state of Mizoram has brought much development for the state as well as for the people. But development cannot be seen immensely as the connectivity within the state is in very bad shape. For the accomplishment and flourish of the so-called ‘Act East Policy’ good connectivity within the state is a must. Keywords : Connectivity, Globalization, Flourish, Transport. Introduction Globalization integrates and mobilizes the cultural values of the people. Many states and countries are amalgamated and mutated due to globalization. It has a gigantic effect on the social, economic, political, cultural, and way of life. Globalization is the progression over which societies and economies which is incorporated over cross border flow of ideas, technology, capital, communication, goods and services, and that of information. The process of globalization began in the 20th century; as a result, the improvement of infrastructure and transportation and communication, international trade, and business gradually grew rapidly. Due to this, the way of life, livelihood, and culture of the Mizo has immensely changed. -

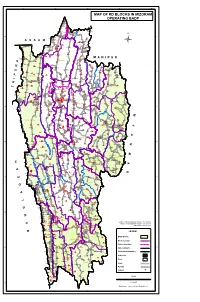

Map of Rd Blocks in Mizoram Operating Badp

92°20'0"E 92°40'0"E 93°60'0"E 93°20'0"E 93°40'0"E MAP OF RD BLOCKS IN MIZORAM Vairengte II OPERATING BADP Vairengte I Saihapui (V) Phainuam Chite Vakultui Saiphai Zokhawthiang North Chhimluang North Chawnpui Saipum Mauchar Phaisen Bilkhawthlir N 24°20'0"N 24°20'0"N Buhchang Bilkhawthlir S Chemphai North Thinglian Bukvannei I Tinghmun BuBkvIaLnKneHi IAI WTHLIR Parsenchhip Saihapui (K) Palsang Zohmun Builum Sakawrdai(Upper) Thinghlun(Lushaicherra) Hmaibiala Veng Rengtekawn Kanhmun South Chhimluang North Hlimen Khawpuar Lower Sakawrdai Luimawi KOLASIB N.Khawdungsei Vaitin Pangbalkawn Hriphaw Luakchhuah Thingsat Vervek E.Damdiai Bungthuam Bairabi New_Vervek Meidum North Thingdawl Thingthelh Lungsum Borai Saikhawthlir Rastali Dilzau H Thuampui(Zawlnuam) Suarhliap R Vengpuh i(Zawlnuam) i Chuhvel Sethawn a k DARLAWN g THINGDAWL Ratu n a Zamuang Kananthar L Bualpui Bukpui Zawlpui Damdiai Sunhluchhip Lungmawi Rengdil N.Khawlek Hortoki Sailutar Sihthiang R North Kawnpui I i R Daido a Vawngawnzo l Vanbawng v i Tlangkhang Kawnpui w u a T T v Mualvum North Chaltlang N.Serzawl i u u Chiahpui i N.E.Tlangnuam Khawkawn s T Darlawn a 24°60'0"N 24°60'0"N Lamherh R Kawrthah Khawlian Mimbung K Sarali North Sabual Sawleng Chilui Zanlawn N.E.Khawdungsei Saitlaw ZAWLNUAM Lungmuat Hrianghmun SuangpuilaPwnHULLEN Vengthar Tumpanglui Teikhang Venghlun Chhanchhuahna kepran Khamrang Tuidam Bazar Veng Nisapui MAMIT Phaizau Phuaibuang Liandophai(Bawngva) E.Phaileng Serkhan Luangpawn Mualkhang Darlak West Serzawl Pehlawn Zawngin Sotapa veng Sentlang T l Ngopa a Lungdai -

In the Fast Tract Court Lunglei Judicial District: Lunglei

IN THE FAST TRACT COURT LUNGLEI JUDICIAL DISTRICT: LUNGLEI. ……………………….. Regd.No. 367/11 Crl.Tr.No. 161/2011 u/s 302/468/341 IPC r/w 6(1)(a) IPP Rules Ref: Lawngtlai P/S/ Case.No. 132/94. State of Mizoram. ………… Complainant Vrs Dawncheuva……………………..Accused. Date of hearing……………………..18/2/2012 Date of Judgment &Order ……….. 8/3/2013 BEFORE Lucy Lalrinthari, District & Sessions Judge PRESENT For the Prosecution - ZDL Pianmawia, P.P. For the Defence - B.Gupta, Advocate JUGEMENT & ORDER 1. The accused Dawncheuva S/o Sawnkhupa of Hmunnuam, Lawngtlai District, Mizoram has been facing trial in connection with Lawngtlai P/S/ Case No. 132/1994 u/s 302/468/34 IPC r/w 6(1)(a) IPP Rules Vide Crl.Tr. No.161/2009 the case having stood till today, the court delivers the following judgment. 2. The prosecution story of the case in brief is that on 23/11/1994, S.I. Thanawrha O/C Bungtlang out-post submitted FIR before the Officer-in- charge Lawngtlai P/S to the effect that on 19/11/1994 @ 5:00 PM he received a secret information from source that one Dawncheuva was seen at Bungtlang South on 19/11/94 while he was boarded at one truck. But his friend Kapkhanthanga who was also went to Bangladesh side along with him (Dawncheuva) was not seen. Source deeply suspected that Kapkhanthanga was killed by Dawncheuva and requested him to enquire about the matter. He along with parties rushed to Hmunnuam village to 2 enquire about the matter on 20/11/94 @ 5:00 AM.