A HISTORY of INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY in 50 OBJECTS Edited by CLAUDY OP DEN KAMP and DAN HUNTER 10 Corset Kara W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sun Also Rises a Book Catalogue from Capitol Hill Books and Riverby Books

The Sun Also Rises A Book Catalogue from Capitol Hill Books and Riverby Books January 27, 2017 On Hemingway, the Lost Generation, Cocktails, and Bullfighting This winter, Shakespeare Theater Company will perform The Select, a play based on Ernest Hemingway’s iconic novel The Sun Also Rises. To kick off the performance, Capitol Hill Books and Riverby Books have joined forces to assemble a collection of books and other materials related to Hemingway and the “Lost Generation.” Our catalog includes various editions (rare, medium rare, and reading copies) of all of Hemingway’s major works, and many associated materials. For instance, we have a program from a 1925 bullfight in Barcelona, vintage cocktail books, a two volume Exotic Cooking and Drinking Book, and an array of books from Hemingway’s peers and mentors. On Jan. 27th, the Pen Faulkner Foundation, the Shakespeare Theater Company, and the Hill Center are hosting an evening retrospective of Hemingway’s writing. Throughout the evening, actors, scholars, and writers will read, praise, and excoriate Hemingway. Meanwhile mixologists will sling drinks with a Hemingway theme, and we will be there to discuss Gertrude Stein, bullfighting, Death in the Gulfstream, and to talk and sell books. All of the materials in this catalog will be for sale there, and both Riverby and Capitol Hill Books will have displays at our stores set up throughout the month of February. So grab a glass of Pernod, browse through the catalog, and let us know if anything is of interest to you. Contact information is below. We hope to see you on the 27th, but if not come by the shop or give us a call. -

Rezervirano Mjesto Za Tekst

The Story of Woman Anna Eleanor Roosevelt (born October 11, 1884, New York, New York, U.S. — died November 7, 1962, New York City, New York)) She was a leader in her own right and in volved in numerous humanitarian causes throughout her life. By the 1920s she was involved in Democratic Party politics and numerous social reform organizations. In the White House, she was one of the most active first ladies in history and worked for political, racial and social justice. After President Roosevelt’s death, Eleanor was a delegate to the United Nations and continued to serve as an advocate for a wide range of human rights issues. Find more on: https://www.history.com/topics/first-ladies/eleanor-roosevelt https://www.britannica.com/biography/Eleanor-Roosevelt Billie Jean King née Billie Jean Moffitt (born November 22, 1943, Long Beach, California, U.S.) American tennis player whose influence and playing style elevated the status of women’s professional tennis beginning in the late 1960s. In her career she won 39 major titles, competing in both singles and doubles. Find more on: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Billie-Jean-King https://www.billiejeanking.com/ Jerrie Mock Geraldine Lois Fredritz (born November 22, 1925, Newark, Ohio — died September 30, 2014, Quincy, Fla.) "Jerrie," was the first woman to fly around the world. On March 19, 1964, Mock took off from Columbus in her plane, the "Spirit of Columbus", a Cessna 180. Mock's trip around the world took twenty-nine days, eleven hours, and fifty-nine minutes, with the pilot returning to Columbus on April 17, 1964. -

1916 at a Glance – Events in America

What was happening at the time that Harvey Browne Presbyterian was chartered? 1916 AT A GLANCE – EVENTS IN AMERICA Woodrow Wilson was re-elected as President. Wilson was the only president with a Ph. D., and one of 10 Presbyterian presidents. Montana suffragist Jeannette Rankin was the first woman elected to Congress – before women had the vote in national elections. Her first vote was against the U.S. entering World War I. In a later, non-consecutive, term, she voted against participating in World War II. The National Park Service was created by an act of Congress “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein ...” At the time, 35 existing parks, including Yellowstone, came under its management. Lincoln's birthplace in Hodgenville Kentucky became a national park site in 1916, but was not managed by the NPS until 1933. A Jim Crow law regarding segregated neighborhoods in Louisville was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. America's first birth control clinic opened in Brooklyn, New York. Nine days after it opened, its director, nurse and activist Margaret Sanger, was subsequently arrested for distributing written instructions on contraception. Emma Goldman (above) was arrested for giving public lessons on birth control. Louis Brandeis, born in Louisville, became the first Jew to be appointed to the Supreme Court. His nomination was hotly contested because, as Justice William O. Douglas wrote, “Brandeis was a militant crusader for social justice … He was dangerous … because of his brilliance … his courage …. because he was incorruptible.” The Statue of Liberty was damaged by shrapnel from a munitions depot explosion in the New York Harbor, attributed to German saboteurs. -

Harry Crosby - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Harry Crosby - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Harry Crosby(4 June 1898 - 10 December 1929) Harry Crosby was an American heir, a bon vivant, poet, publisher, and for some, epitomized the Lost Generation in American literature. He was the son of one of the richest banking families in New England, a member of the Boston Brahmin, and the nephew of Jane Norton Grew, the wife of financier J. P. Morgan, Jr.. As such, he was heir to a portion of a substantial family fortune. He was a volunteer in the American Field Service during World War I, and later served in the U.S. Ambulance Corps. He narrowly escaped with his life. Profoundly affected by his experience in World War I, Crosby vowed to live life on his own terms and abandoned all pretense of living the expected life of a privileged Bostonian. He had his father's eye for women, and in 1920 met Mrs. Richard Peabody (née Mary Phelps Jacob), six years his senior. They had sex within two weeks, and their open affair was the source of scandal and gossip among blue-blood Boston. Mary (or Polly as she was called) divorced her alcoholic husband and to her family's dismay married Crosby. Two days later they left for Europe, where they devoted themselves to art and poetry. Both enjoyed a decadent lifestyle, drinking, smoking opium regularly, traveling frequently, and having an open marriage. Crosby maintained a coterie of young ladies that he frequently bedded, and wrote and published poetry that dwelled on the symbolism of the sun and explored themes of death and suicide. -

The History of Underwear by Zita Thornton

National Trust Photographic Library / Andreas von Einsiedel. Man’s rich satin dressing gown in the Killerton Costume National Trust Photographic Library / Andreas von Einsiedel. 1940s pink nylon camiknickers Collection, 1830s. The dressing gown has and ‘Christian Dior’ stockings in the Killerton Costume Collection, Killerton House, nr Exeter. brown embroidery. Worn to cover up Nylon was a new fabric during and after the Second World War and was considered a luxury. nightwear to receive informal visitors. the history of underwear by Zita Thornton Do you know what links the bristles of a toothbrush with a pair of stockings? Or who banned thick waists? Or who said “Without foundation there is no fashion” Answers. Toothbrush bristles and stockings were the first objects to be made from nylon in the 1830s. And it was Catherine Medici who was fussy about waist sizes at the court of her husband Henri II of France in the sixteenth century. And it was the Paris couturier, Christian Dior who made the last statement about his post war collection in the 1950s. A study of the history of underwear reveals that all three had a significant influence on what women wore beneath their outer garments. The foundation of underwear the wayward flesh of ladies into the fashionable eighteenth century silhouette and The first under garment was a basic moulded the bodies of growing children by chemise. A simple shift of linen or cotton means of cord, canes and whalebones inserted which was worn day or night up until the into canvas channels which were quilted or twentieth century providing a comfortable and stiffened with paste. -

Fashion Forward

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID NEW HAVEN, CT PERMIT #1090 333 Christian Street PO BOX 5043 BTHE MAGAUZINE OFLLET CHOATE ROSEMARY HALL INFALL ’18 Wallingford, CT 06492-3800 Change Service Requested Play the video to find out howSRP student Vincenzo DiNatale ’19 spent his summer interning at the Yale School of Medicine. The Choate Rosemary Hall Bulletin is printed using vegetable-based inks on 100% post consumer recycled paper. This issue saved 101 In this issue: FASHION FORWARD SIGNATURE MOVES SKYLAR HANSEN-RAJ ’20 trees, 42,000 gallons of wastewater, 291 lbs of waterborne waste, and Alums in the world of fashion Choate's Signature Academic Programs Reflections from Choate's Global Programs 9,300 lbs of greenhouse gases from being emitted. 10 FASHION FORWA R D By Rhea hiRshman While “fashion influencer” is probably not the first description that comes to mind when thinking of the School’s array of accomplished alumni and alumnae, a significant number of alums have put their stamp on the world of fashion and style. CORSETS, BEGONE! Born Mary Phelps Jacobs in 1891, and Although fashionable dress for women was beginning known at school as Polly, Caresse Crosby graduated from to change, stiff, unyielding corsets were still in style when Rosemary Hall in 1910. After divorcing her first husband, Polly was attending dances and meeting eligible young Richard Peabody, with whom she had two children, Polly men. Before a debutante ball in 1910, Polly found herself married Harry Crosby. The couple led an extravagant and with a dilemma: her corset showed from under her dress’s sometimes scandalous expatriate lifestyle. -

Intimates a Supplement to WWD July 2009

WWD intimates A Supplement to WWD July 2009 n RomanticR i ffantasiesi come true with spring’s Victorian- infl uenced lingerie. wINTa001B;9.indd 1 7/17/09 4:27:54 PM WWD intimates ®The retailers’ daily newspaper Published by Fairchild Publications Inc., a subsidiary of Advance Publications Inc., 750 Third Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10017 EDWARD NARDOZA Editor in Chief BRIDGET FOLEY Executive Editor JAMES FALLON Editor RICHARD ROSEN Managing Editor DIANNE M. POGODA Managing Editor, Fashion/Special Reports MICHAEL AGOSTA Special Sections Editor BOBBI QUEEN Senior Fashion Editor KARYN MONGET News Editor, Intimates WWD.COM AMY DITULLIO, Managing Editor Bruno Navarro (News Editor); Véronique Hyland (Associate Editor, Fashion); Lauren Benet Stephenson (Associate Editor, Beauty/Lifestyle) CONTRIBUTORS LOUISE BARTLETT JESSICA IREDALE ART DEPARTMENT ANDREW FLYNN, Group Art Director SHARON BER, AMY LOMACCHIO, Associate Art Directors Courtney Mitchell, Kim Gilby, Designers Eric Perry, Junior Designer Tyler Resty, Art Assistant LAYOUT/COPY DESK PETER SADERA Copy Chief MAUREEN MORRISON Deputy Copy Chief LISA KELLY Senior Copy Editor Adam Perkowsky, Kim Romagnuolo, Sarah Protzman Copy Editors PHOTOGRAPHY ANITA BETHEL, Director John Aquino, Talaya Centeno, George Chinsee, Steve Eichner, Kyle Ericksen, Stéphane Feugère, Giovanni Giannoni, Thomas Iannaccone, Tim Jenkins, Davide Maestri, Dominique Maître, Robert Mitra, David Sawyer, Cliff Watts, Kristen Somody Whalen PHOTO CARRIE PROVENZANO, Photo Editor Lexie Moreland, Ashley Linn Martin, Photo Coordinators BUSINESS JOHN COSCIA, Editorial Business Director PATRICK MCCARTHY Chairman and Editorial Director 732-935-1100 | www.hanro.com wINTa_masthead;5.indd 2 7/17/09 1:57:21 PM IN0727_p004_0CA90.indd 1 7/17/09 2:06:43 PM Introducing CONFIDENTIAL by O Lingerie. -

Transition Magazine 1927-1930

i ^ p f f i b A I Writing and art from transition magazine 1927-1930 CONTRIBUTIONS BY SAMUEL BECKETT PAUL BOWLES KAY BOYLE GEORGES BRAQUE ALEXANDER CALDER HART CRANE GIORGIO DE CHIRICO ANDRE GIDE ROBERT GRAVES ERNEST HEMINGWAY JAMES JOYCE C.G. JUNG FRANZ KAFKA PAUL KLEE ARCHIBALD MACLEISH MAN RAY JOAN MIRO PABLO PICASSO KATHERINE ANNE PORTER RAINER MARIA RILKE DIEGO RIVERA GERTRUDE STEIN TRISTAN TZARA WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS AND OTHERS ■ m i , . « f " li jf IT ) r> ’ j vjffjiStl ‘■vv ■H H Iir ■ nr ¥ \I ififl $ 14.95 $388 in transition: A Paris Anthology IK i\ Paris transition An Anthology transition: A Paris Anthology WRITING AND ART FROM transition MAGAZINE 1927-30 With an Introduction by Noel Riley Fitch Contributions by Samuel BECKETT, Paul BOWLES, Kay BOYLE, Georges BRAQUE, Alexander CALDER, Hart CRANE, Giorgio DE CHIRICO, Andre GIDE, Robert GRAVES, Ernest HEMINGWAY, James JOYCE, C. G. JUNG, Franz KAFKA, Paul KLEE, Archibald MacLEISH, MAN RAY, Joan MIRO, Pablo PICASSO, Katherine Anne PORTER, Rainer Maria RILKE, Diego RIVERA, Gertrude STEIN, Tristan TZARA, William Carlos WILLIAMS and others A n c h o r B o o k s DOUBLEDAY NEW YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY AUCKLAND A n A n c h o r B o o k PUBLISHED BY DOUBLEDAY a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. 666 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10103 A n c h o r B o o k s , D o u b l e d a y , and the portrayal of an anchor are trademarks of Doubleday, a division of B antam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. -

US 2009/0042477 A1 Redenius (43) Pub

US 20090042477A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0042477 A1 Redenius (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 12, 2009 (54) ADJUSTABLE LIFT SYSTEM FOR BRAS Publication Classification (51) Int. Cl. (76) Inventor: Ronald Redenius, Shingle Springs, A4IC 3/10 (2006.01) CA (US) A4D 7700 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ...................... 450/41; 450/56: 450/55; 2/67 Correspondence Address: (57) ABSTRACT ROBERT R. WATERS, ESQ. WATERS LAW OFFICE, PLLC A lifting and shaping system for a bra or other garment uses 633 SEVENTH STREET lift platforms shaped to fit into the cups of the bra and formed HUNTINGTON, WV 25701 (US) from thin material. The lift platforms are attached to the garment toward the center of the garment. Connectors having one end attached to the lift platformand the otherendattached (21) Appl. No.: 12/254,556 to a slide on the E. strap adjust the lift of the lift platform when the slide is moved. Flexible shaping members (22) Filed: Oct. 20, 2008 distribute the lift of the lift platforms and maintain the natural shape of the breasts as they are lifted. Smoothing shields ease Related U.S. Application Data the movement of the lift platforms and connectors within the cloth confines of the breast cups. The flexible shaping mem (63) Continuation of application No. 11/059,194, filed on bers may also perform some of the functions of a smoothing Feb. 16, 2005, now Pat. No. 7,452,260. shield. Patent Application Publication Feb. 12, 2009 Sheet 1 of 6 US 2009/0042477 A1 Patent Application Publication Feb. -

Le Double Jeu De La Brassière Ludmila Bovet

Document generated on 09/27/2021 2 a.m. Québec français Dessus ou dessous, devant ou derrière? Le double jeu de la brassière Ludmila Bovet Chanson et littérature Number 119, Fall 2000 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/56042ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Publications Québec français ISSN 0316-2052 (print) 1923-5119 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Bovet, L. (2000). Dessus ou dessous, devant ou derrière? Le double jeu de la brassière. Québec français, (119), 96–99. Tous droits réservés © Les Publications Québec français, 2000 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Dessus dey an ou Le double jeu de la brassière u'y a-t-il de commun entre une partie de Camisole de nuit l'armure du Moyen Âge, une camisole du En glieu d'haut-de- Les dictionnaires du XVIIe siècle définissent brassière par XVIIe siècle, une veste tricotée pour nourris chausses, ils portant « a waist-coat, for a woman ; or a child » (Cotgrave, diction sons et un soutien-gorge ? Le mot brassière, un garde-robe aussi naire français-anglais datant de 1611 ) ; également par « es nent. Et quelle est la base du mot brassière ? large que d'ici à pèce de camisole que les femmes et les enfants mettent LQe simple mo t bras. -

The Baroness Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven's New York

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_May 17, 2006_______ I, _Jaime L.M. Thompson___________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: “A Wild Apparition Liberated from constraint”: The Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s New York Dada Street Performances and Costume Art of 1913-1923 This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr. Theresa Leininger-Miller___ Dr. Joan Seeman Robinson_______ Dr. Kimberly Paice___________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “A Wild Apparition Liberated from Constraint”: The Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s New York Dada Street Performances and Costume Art of 1913-1923 A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Jaime L.M. Thompson May 2006 Thesis Chair: Dr. Theresa Leininger-Miller Abstract After eighty years of obscurity the German Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927) has reemerged as a valuable subject of study. The Baroness was an artist and a writer whose media included poetry, collage, sculpture, performance and costume art. In chapter one I firmly establish the Baroness’s position as a Dada artist through examining her shared connections with the emergence of European Dada. In final chapters I will examine the most under-examined aspect of the Baroness’s various mediums—her performance and costume art. In the second chapter I will explore the Baroness’s work utilizing performative and feminist theories in relation to Marcel Duchamp’s female alter ego Rrose Sélavy. -

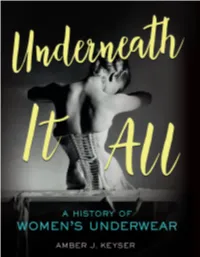

Amber J. Keyser

Did you know that the world’s first bra dates to the fifteenth century? Or that wearing a nineteenth-century cage crinoline was like having a giant birdcage strapped around your waist? Did you know that women during WWI donated the steel stays from their corsets to build battleships? For most of human history, the garments women wore under their clothes were hidden. The earliest underwear provided warmth and protection. But eventually, women’s undergarments became complex structures designed to shape their bodies to fit the fashion ideals of the time. When wide hips were in style, they wore wicker panniers under their skirts. When narrow waists were popular, women laced into corsets that cinched their ribs and took their breath away. In the modern era, undergarments are out in the open. From the designer corsets Madonna wore on stage to Beyoncé’s pregnancy announcement on Instagram, lingerie is part of everyday wear, high fashion, fine art, and innovative technological advances. This feminist exploration of women’s underwear— with a nod to codpieces, tighty- whities, and boxer shorts along the way—reveals the intimate role lingerie plays in defining women’s bodies, sexuality, gender identity, and body image. It is a story of control and restraint but also female empowerment and self- expression. You will never look at underwear the same way again. REINFORCED BINDING AMBER J. KEYSER TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BOOKS / MINNEAPOLIS For Lacy, who puts the voom in va-va-voom Cover photograph: Photographer Horst P. Horst took this image of a Mainbocher corset in 1939. It is one of the most iconic photos of fashion photography.