British-Based Corporations and the Tax 'Race to the Bottom'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Governance

Strategic report Governance and remuneration Financial statements Investor information Corporate Governance In this section Chairman’s Governance statement 78 The Board 80 Corporate Executive Team 83 Board architecture 85 Board roles and responsibilities 86 Board activity and principal decisions 87 Our purpose, values and culture 90 The Board’s approach to engagement 91 Board performance 94 Board Committee information 96 Our Board Committee reports 97 Section 172 statement 108 Directors’ report 109 GSK Annual Report 2020 77 Chairman’s Governance statement In last year’s Governance statement, I explained that our primary Education and focus on Science objective for 2020 was to ensure there was clarity between the Given the critical importance of strengthening the pipeline, Board and management on GSK’s execution of strategy and its the Board has benefitted from devoting a higher proportion of operational priorities. We have aligned our long-term priorities its time in understanding the science behind our strategy and of Innovation, Performance and Trust powered by culture testing its application. It is important that the Board has a and agreed on the metrics to measure delivery against them. working understanding of the key strategic themes upon The Board’s annual cycle of meetings ensures that all major which our R&D strategy is based. These themes have been components of our strategy are reviewed over the course complemented by Board R&D science thematic deep dives. of the year. Our focus was on the fundamentals of our strategy: human The COVID-19 pandemic impacted and dominated all our genetics, the immune system and AI and ML, as well as to lives for the majority of 2020. -

To Arrive at the Total Scores, Each Company Is Marked out of 10 Across

BRITAIN’S MOST ADMIRED COMPANIES THE RESULTS 17th last year as it continues to do well in the growing LNG business, especially in Australia and Brazil. Veteran chief executive Frank Chapman is due to step down in the new year, and in October a row about overstated reserves hit the share price. Some pundits To arrive at the total scores, each company is reckon BG could become a take over target as a result. The biggest climber in the top 10 this year is marked out of 10 across nine criteria, such as quality Petrofac, up to fifth from 68th last year. The oilfield of management, value as a long-term investment, services group may not be as well known as some, but it is doing great business all the same. Its boss, Syrian- financial soundness and capacity to innovate. Here born Ayman Asfari, is one of the growing band of are the top 10 firms by these individual measures wealthy foreign entrepreneurs who choose to make London their operating base and home, to the benefit of both the Exchequer and the employment figures. In fourth place is Rolls-Royce, one of BMAC’s most Financial value as a long-term community and environmental soundness investment responsibility consistent high performers. Hardly a year goes past that it does not feature in the upper reaches of our table, 1= Rightmove 9.00 1 Diageo 8.61 1 Co-operative Bank 8.00 and it has topped its sector – aero and defence engi- 1= Rotork 9.00 2 Berkeley Group 8.40 2 BASF (UK & Ireland) 7.61 neering – for a decade. -

Annex 1: Parker Review Survey Results As at 2 November 2020

Annex 1: Parker Review survey results as at 2 November 2020 The data included in this table is a representation of the survey results as at 2 November 2020, which were self-declared by the FTSE 100 companies. As at March 2021, a further seven FTSE 100 companies have appointed directors from a minority ethnic group, effective in the early months of this year. These companies have been identified through an * in the table below. 3 3 4 4 2 2 Company Company 1 1 (source: BoardEx) Met Not Met Did Not Submit Data Respond Not Did Met Not Met Did Not Submit Data Respond Not Did 1 Admiral Group PLC a 27 Hargreaves Lansdown PLC a 2 Anglo American PLC a 28 Hikma Pharmaceuticals PLC a 3 Antofagasta PLC a 29 HSBC Holdings PLC a InterContinental Hotels 30 a 4 AstraZeneca PLC a Group PLC 5 Avast PLC a 31 Intermediate Capital Group PLC a 6 Aveva PLC a 32 Intertek Group PLC a 7 B&M European Value Retail S.A. a 33 J Sainsbury PLC a 8 Barclays PLC a 34 Johnson Matthey PLC a 9 Barratt Developments PLC a 35 Kingfisher PLC a 10 Berkeley Group Holdings PLC a 36 Legal & General Group PLC a 11 BHP Group PLC a 37 Lloyds Banking Group PLC a 12 BP PLC a 38 Melrose Industries PLC a 13 British American Tobacco PLC a 39 Mondi PLC a 14 British Land Company PLC a 40 National Grid PLC a 15 BT Group PLC a 41 NatWest Group PLC a 16 Bunzl PLC a 42 Ocado Group PLC a 17 Burberry Group PLC a 43 Pearson PLC a 18 Coca-Cola HBC AG a 44 Pennon Group PLC a 19 Compass Group PLC a 45 Phoenix Group Holdings PLC a 20 Diageo PLC a 46 Polymetal International PLC a 21 Experian PLC a 47 -

Ftse4good UK 50

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE4Good UK 50 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Group 0.81 UNITED GlaxoSmithKline 5.08 UNITED Rentokil Initial 0.67 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Anglo American 2.56 UNITED Halma 0.74 UNITED Rio Tinto 4.68 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Antofagasta 0.36 UNITED HSBC Hldgs 6.17 UNITED Royal Dutch Shell A 4.3 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Associated British Foods 0.56 UNITED InterContinental Hotels Group 0.64 UNITED Royal Dutch Shell B 3.75 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AstraZeneca 8.25 UNITED International Consolidated Airlines 0.47 UNITED Schroders 0.28 UNITED KINGDOM Group KINGDOM KINGDOM Aviva 1.15 UNITED Intertek Group 0.65 UNITED Segro 0.95 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Barclays 2.1 UNITED Legal & General Group 1.1 UNITED Smith & Nephew 0.99 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM BHP Group Plc 3.2 UNITED Lloyds Banking Group 2.39 UNITED Smurfit Kappa Group 0.74 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM BT Group 1.23 UNITED London Stock Exchange Group 2.09 UNITED Spirax-Sarco Engineering 0.72 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Burberry Group 0.6 UNITED Mondi 0.67 UNITED SSE 1.13 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Coca-Cola HBC AG 0.37 UNITED National Grid 2.37 UNITED Standard Chartered 0.85 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Compass Group 1.96 UNITED Natwest Group 0.77 UNITED Tesco 1.23 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM CRH 2.08 UNITED Next 0.72 UNITED Unilever 7.99 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM -

Constituents & Weights

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE 100 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Group 0.59 UNITED GlaxoSmithKline 3.7 UNITED RELX 1.88 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Admiral Group 0.35 UNITED Glencore 1.97 UNITED Rentokil Initial 0.49 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Anglo American 1.86 UNITED Halma 0.54 UNITED Rightmove 0.29 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Antofagasta 0.26 UNITED Hargreaves Lansdown 0.32 UNITED Rio Tinto 3.41 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashtead Group 1.26 UNITED Hikma Pharmaceuticals 0.22 UNITED Rolls-Royce Holdings 0.39 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Associated British Foods 0.41 UNITED HSBC Hldgs 4.5 UNITED Royal Dutch Shell A 3.13 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AstraZeneca 6.02 UNITED Imperial Brands 0.77 UNITED Royal Dutch Shell B 2.74 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Auto Trader Group 0.32 UNITED Informa 0.4 UNITED Royal Mail 0.28 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Avast 0.14 UNITED InterContinental Hotels Group 0.46 UNITED Sage Group 0.39 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aveva Group 0.23 UNITED Intermediate Capital Group 0.31 UNITED Sainsbury (J) 0.24 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aviva 0.84 UNITED International Consolidated Airlines 0.34 UNITED Schroders 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM Group KINGDOM KINGDOM B&M European Value Retail 0.27 UNITED Intertek Group 0.47 UNITED Scottish Mortgage Inv Tst 1 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM BAE Systems 0.89 UNITED ITV 0.25 UNITED Segro 0.69 UNITED KINGDOM -

Notice of Annual General Meeting 2011

ASSOCIATED BRITISH FOODS PLC (incorporated and registered in England and Wales under number 00293262) NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE AttENTION If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you are Notice of the annual general meeting of Associated British Foods plc recommended to seek your own independent financial advice to be held at 11.00 am on Friday 9 December 2011 at Congress from a stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or Centre, 28 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3LS is set out in other financial advisor authorised under the Financial Services this document. and Markets Act 2000. A Form of Proxy for use at the annual general meeting is enclosed. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all of your Associated To be valid, the Form of Proxy should be completed and returned British Foods plc shares, please send this document, together with in accordance with the instructions to Equiniti at Aspect House, the accompanying documents (but not the personalised Form of Spencer Road, Lancing BN99 6GU as soon as possible but in any Proxy), as soon as possible to the purchaser or transferee, or to event so as to arrive not later than 11.00 am on Wednesday, the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or 7 December 2011. transfer was effected, for delivery to the purchaser or transferee. Associated British Foods Notice of Meeting 2011 2 Notice of meeting NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN thAT the Ordinary business To propose and, if thought fit, to pass the seventy-siXth AnnUAL GenerAL following resolutions as ordinary resolutions: Meeting OF AssociAteD British Resolution 1 FooDS PLC (the ‘ComPAny’) wiLL To receive the accounts and the reports of the be heLD AT Congress Centre, directors and the auditors thereon for the year 28 GREAT RUsseLL Street, LonDon ended 17 September 2011. -

BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic Report 1

BT Group plc Group BT Annual Report 2020 Beyond Limits BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic report 1 New BT Halo. ... of new products and services Contents Combining the We launched BT Halo, We’re best of 4G, 5G our best ever converged Strategic report connectivity package. and fibre. ... of flexible TV A message from our Chairman 2 A message from our Chief Executive 4 packages About BT 6 investing Our range of new flexible TV Executive Committee 8 packages aims to disrupt the Customers and markets 10 UK’s pay TV market and keep Regulatory update 12 pace with the rising tide of in the streamers. Our business model 14 Our strategy 16 Strategic progress 18 ... of next generation Our stakeholders 24 future... fibre broadband Culture and colleagues 30 We expect to invest around Introducing the Colleague Board 32 £12bn to connect 20m Section 172 statement 34 premises by mid-to-late-20s Non-financial information statement 35 if the conditions are right. Digital impact and sustainability 36 Our key performance indicators 40 Our performance as a sustainable and responsible business 42 ... of our Group performance 43 A letter from the Chair of Openreach 51 best-in-class How we manage risk 52 network ... to keep us all Our principal risks and uncertainties 53 5G makes a measurable connected Viability statement 64 difference to everyday During the pandemic, experiences and opens we’re helping those who up even more exciting need us the most. Corporate governance report 65 new experiences. Financial statements 117 .. -

The Second Release of Prima & Ultima

Notes to Editors: Recommended Retail Selling Price for the full set is £23,500 (including tax and duty) in UK Bottle sizes: 70cl Global Registration Live: 4th August 2021 Global Registration Closes: 23rd August 2021 Link for registration: www.theprimaandultimacollection.com The Second Release of Prima & Ultima: All of the Single Malt Scotch Whiskies included are natural cask strength, non-chill filtered, with no colour added. Auchroisk 1974 47-Year-Old | 48.7% ABV Bottled: 26.01.2121 | Single Refill European Oak Butt Number Bottled: 382 | Mulben, Speyside The very first cask to be filled at Auchroisk when distilling began on 15th January 1974, this cask has been kept back for many years for its character and its rarity. Remarkably rich and spicy, with fruity aromas and smooth flavours. Lagavulin 1992 28-Year-Old | 47.7% ABV Bottled: 20.01.2021 | 5 Freshly Charred American Oak Hogsheads Number Bottled: 1,081 | Port Ellen, Isle of Islay The first of its kind from a small experimental batch matured entirely on Islay in freshly charred American Oak hogsheads, this is a very rare Lagavulin. Time has mellowed the smoky nature of this spirit making it elegantly rounded and smooth in texture. Linkwood 1981 39-Year-Old | 52.9% ABV Bottled: 25.01.21 | 4 new American Oak casks, PX Oloroso seasoned Number Bottled: 701 | Elgin | Speyside Part of the first pioneering trial exploring different maturation processes at the distillery, this triple- rare expression gives it an incredible depth. The rich flavours and aromas of a PX/Oloroso-seasoned cask are deeply integrated with the creamy texture and spicy, toasted characters brought by the new American Oak. -

ABF Annual Report & Accounts 2013

ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2013 Associated British Foods plc Annual Report and Accounts 2013 CONTENTS Directors’ report Business review 1 2013 highlights 2 Group business model and strategy 4 Our businesses at a glance 6 Business strategies 8 Chairman’s statement 20 Operating review 36 Financial review Governance 40 Corporate responsibility 44 Board of directors 46 Corporate governance 62 Remuneration report 76 Other disclosures 80 Statement of directors’ responsibilities in respect of the annual report and the financial statements 81 Independent auditors’ report Financial statements 82 Consolidated income statement 83 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 84 Consolidated balance sheet Our PLC website is available on multiple platforms from mobile devices to laptops. For a more interactive report, 85 Consolidated cash flow statement go online at abf.co.uk/ar2013 86 Consolidated statement of changes in equity For an in-depth look at our sustainable approach to 87 Significant accounting policies business refer to the Associated British Foods’ Corporate 92 Accounting estimates and judgements Responsibility Report 2013 which is available at 93 Notes forming part of the financial abf.co.uk/responsibility statements 127 Company financial statements 132 Progress report Shareholder information 132 Company directory 2013 HIGHLIGHTS 1 Associated British Foods • Another year of strong growth and Directors’ report | Business review | is a diversified international cash generation food, ingredients and • Remarkable performance by Primark -

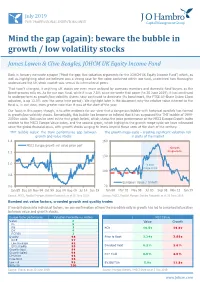

Mind the Gap (Again): Beware the Bubble in Growth / Low Volatility Stocks

July 2019 FOR PROFESSIONAL INVESTORS ONLY Mind the gap (again): beware the bubble in growth / low volatility stocks James Lowen & Clive Beagles, JOHCM UK Equity Income Fund Back in January we wrote a paper (‘Mind the gap: five valuation arguments for the JOHCM UK Equity Income Fund’) which, as well as highlighting what we believed was a strong case for the value contained within our fund, underlined how thoroughly undervalued the UK stock market was versus its international peers. That hasn’t changed, if anything UK stocks are even more unloved by overseas investors and domestic fund buyers as the Brexit process rolls on. As for our own fund, while it is up 7.8% since we wrote that paper (to 30 June 2019), it has continued to underperform as growth/low volatility shares have continued to dominate (its benchmark, the FTSE All-Share Index 12pm adjusted, is up 13.0% over the same time period). We highlight later in the document why the relative value inherent in the fund is, in our view, even greater now than it was at the start of the year. Our focus in this paper, though, is to offer evidence for our view that a dangerous bubble with historical parallels has formed in growth/low volatility stocks. Remarkably, this bubble has become so inflated that it has surpassed the TMT bubble of 1999- 2000 in scale. This can be seen in the first graph below, which shows the price performance of the MSCI Europe Growth index relative to the MSCI Europe Value index, and the second graph, which highlights the growth mega-cycle we have witnessed since the global financial crisis, with growth stocks surging to levels beyond those seen at the start of the century. -

DIAGEO Plc, of 1933 and SECTION 21C of the SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT of 1934, Respondent

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Before the SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 Release No. 10756 / February 19, 2020 SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Release No. 88234 / February 19, 2020 ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDING File No. 3-19701 ORDER INSTITUTING CEASE-AND- In the Matter of DESIST PROCEEDINGS, PURSUANT TO SECTION 8A OF THE SECURITIES ACT DIAGEO plc, OF 1933 AND SECTION 21C OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934, Respondent. MAKING FINDINGS, AND IMPOSING A CEASE-AND-DESIST ORDER I. The Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”) deems it appropriate and in the public interest that cease-and-desist proceedings be, and hereby are, instituted pursuant to Section 8A of the Securities Act of 1933 (“Securities Act”) and Section 21C of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (“Exchange Act”) against DIAGEO plc (“Diageo” or “Respondent”). II. In anticipation of the institution of these proceedings, Respondent has submitted an Offer of Settlement (the “Offer”) which the Commission has determined to accept. Solely for the purpose of these proceedings and any other proceedings brought by or on behalf of the Commission, or to which the Commission is a party, and without admitting or denying the findings herein, except as to the Commission’s jurisdiction over it and the subject matter of these proceedings, which are admitted, Respondent consents to the entry of this Order Instituting Cease-and-Desist Proceedings, Pursuant to Section 8A of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 21C of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Making Findings, and Imposing a Cease-and-Desist Order (“Order”), as set forth below. -

Inaugural Groceries Code Adjudicator Conference

Inaugural Groceries Code Adjudicator Conference Monday 23rd June 2014 Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre Broad Sanctuary, Westminster, London SW1P 3GG INAUGURAL GROCERIES CODE ADJUDICATOR CONFERENCE 2014 Contents Conference programme 2 Supplementary programme 4 Speakers’ biographies 5 Delegates list 8 Groceries Supply Code of Practice 14 Contact the GCA at: Website: www.gov.uk/gca Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0207 271 0221 See the GCA website for copies of presentations, our annual report and a final delegate list. 1 INAUGURAL GROCERIES CODE ADJUDICATOR CONFERENCE 2014 Conference programme 23rd June 2014 9:00am – 9:30am Registration Tea and coffee will be available 9:30am – 10:00am Introduction to the Groceries Code INTRODUCTION Adjudicator Christine Tacon The Adjudicator, appointed to oversee Groceries Code Adjudicator compliance with the Groceries Supply Code of Practice (the Code), formally welcomes everyone and explains her role 10:00am – 10:20am Role of the Trade Association PRESENTATION The Chairman of British Brands Group explains Andrew McCarthy how trade associations support suppliers to Chairman raise Code issues with the GCA and retailers British Brands Group 10:20am – 11:00am Role of the Code Compliance Officer PRESENTATION Two Code Compliance Officers (CCO) discuss Steven Butts their experience of being a CCO Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc David Ward Tesco plc 11:00am – 11:30am Sector research – the results PRESENTATION YouGov’s CEO presents findings from the Stephan Shakespeare GCA-commissioned research to explore