Umidissertation Information Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aetna 2008 African American History Calendar

© 2007 Aetna Inc. Aetna 2007 © Aetna 2008 African American History Calendar Health Marginal Literacy, A Growing Issue in Health Care Literacy By Janet Ohene-Frempong, M.S. Patients are often confused. Health care But there’s also good news: Reading scores for blacks and concepts. They may be unclear about what to do and providers often don’t know it. have gone up in the 10 years since the last national why to do it. They read well. But, they are just not familiar Many people are not aware of the problem of marginal survey was conducted. So the gap is closing. with complex health care issues and systems. They have literacy, which means being able to read, but not with low health literacy. real skill. Individuals fall into poor health for many reasons. Shame can get in the way of good There also are many reasons why people fail to follow health care. Steps can be taken to address the issue. through on what their health care providers ask them to People go out of their way to hide from their doctors that they Marginal health literacy is a serious problem. Steps can do. One main reason for both of these issues can be linked can’t read well. This is true no matter what a person’s age or be taken to correct it: to reading skills. More people than we think do not read race. Researchers have shown that “because of the shame that Expand awareness across the nation about this issue. they hold, some patients may be intimidated and less likely to well. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

1 LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD ewis Hayden died in Boston on Sunday morning April 7, 1889. L His passing was front- page news in the New York Times as well as in the Boston Globe, Boston Herald and Boston Evening Transcript. Leading nineteenth century reformers attended the funeral including Frederick Douglass, and women’s rights champion Lucy Stone. The Governor of Massachusetts, Mayor of Boston, and Secretary of the Commonwealth felt it important to participate. Hayden’s was a life of real signi cance — but few people know of him today. A historical marker at his Beacon Hill home tells part of the story: “A Meeting Place of Abolitionists and a Station on the Underground Railroad.” Hayden is often described as a “man of action.” An escaped slave, he stood at the center of a struggle for dignity and equal rights in nine- Celebrate teenth century Boston. His story remains an inspiration to those who Black Historytake the time to learn about Month it. Please join the Town of Framingham for a special exhibtion and visit the Framingham Public Library for events as well as displays of books and resources celebrating the history and accomplishments of African Americans. LEWIS HAYDEN and the UNDERGROUND RAILROAD Presented by the Commonwealth Museum A Division of William Francis Galvin, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Opens Friday February 10 Nevins Hall, Framingham Town Hall Guided Tour by Commonwealth Museum Director and Curator Stephen Kenney Tuesday February 21, 12:00 pm This traveling exhibit, on loan from the Commonwealth Museum will be on display through the month of February. -

Stories Matter: the Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature (Pp

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 339 CS 512 399 AUTHOR Fox, Dana L., Ed.; Short, Kathy G., Ed. TITLE Stories Matter: The Complexity of CulturalAuthenticity in Children's Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana,IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-4744-5 PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 345p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers ofEnglish, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana,.IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 47445: $26.95members; $35.95 nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010).-- Collected Works General (020) -- Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Literature; *Cultural Context; ElementaryEducation; *Literary Criticism; *Multicultural Literature;Picture Books; Political Correctness; Story Telling IDENTIFIERS Trade Books ABSTRACT The controversial issue of cultural authenticity inchildren's literature resurfaces continually, always elicitingstrong emotions and a wide range of perspectives. This collection explores thecomplexity of this issue by highlighting important historical events, current debates, andnew questions and critiques. Articles in the collection are grouped under fivedifferent parts. Under Part I, The Sociopolitical Contexts of Cultural Authenticity, are the following articles: (1) "The Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature:Why the Debates Really Matter" (Kathy G. Short and Dana L. Fox); and (2)"Reframing the Debate about Cultural Authenticity" (Rudine Sims Bishop). Under Part II,The Perspectives of Authors, -

The Magazine of the Broadside WINTER 2012

the magazine of the broadSIDE WINTER 2012 LOST& FOUND page 2 FEBRUARY 27–AUGUST 25, 2012 broadSIDE THE INSIDE STORY the magazine of the Joyous Homecoming LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA WINTER 2012 Eighteenth-century Stafford County records librarian of virginia discovered in New Jersey are returned to Virginia Sandra G. Treadway arly this year the Library will open an exhibition entitled Lost library board chair Eand Found. The exhibition features items from the past that Clifton A. Woodrum III have disappeared from the historical record as well as documents and artifacts, missing and presumed gone forever, that have editorial board resurfaced after many years. Suddenly, while the curators were Janice M. Hathcock Ann E. Henderson making their final choices about exhibition items from our Gregg D. Kimball collections, the Library was surprised to receive word of a very Mary Beth McIntire special “find” that has now made its way back home to Virginia. During the winter of 1862–1863, more than 100,000 Union editor soldiers with the Army of the Potomac tramped through and Ann E. Henderson camped in Stafford County, Virginia. By early in December 1862, the New York Times reported that military activity had left the copy editor Emily J. Salmon town of Stafford Court House “a scene of utter ruin.” One casualty of the Union occupation was the “house of records” located graphic designer behind the courthouse. Here, the Times recounted, “were deposited all the important Amy C. Winegardner deeds and papers pertaining to this section for a generation past.” Documents “were found lying about the floor to the depth of fifteen inches or more around the door-steps and in photography the door-yard.” Anyone who has ever tried to research Stafford County’s early history can Pierre Courtois attest to the accuracy of the newspaper’s prediction that “it is impossible to estimate the inconvenience and losses which will be incurred by this wholesale destruction.” contributors Barbara C. -

A Narrative of Augusta Baker's Early Life and Her Work As a Children's Librarian Within the New York Public Library System B

A NARRATIVE OF AUGUSTA BAKER’S EARLY LIFE AND HER WORK AS A CHILDREN’S LIBRARIAN WITHIN THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM BY REGINA SIERRA CARTER DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Educational Policy Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor James Anderson, Chair Professor Anne Dyson Professor Violet Harris Associate Professor Yoon Pak ABSTRACT Augusta Braxston Baker (1911-1998) was a Black American librarian whose tenure within the New York Public Library (NYPL) system lasted for more than thirty years. This study seeks to shed light upon Baker’s educational trajectory, her career as a children’s librarian at NYPL’s 135th Street Branch, her work with Black children’s literature, and her enduring legacy. Baker’s narrative is constructed through the use of primary source materials, secondary source materials, and oral history interviews. The research questions which guide this study include: 1) How did Baker use what Yosso described as “community cultural wealth” throughout her educational trajectory and time within the NYPL system? 2) Why was Baker’s bibliography on Black children’s books significant? and 3) What is her lasting legacy? This study uses historical research to elucidate how Baker successfully navigated within the predominantly White world of librarianship and established criteria for identifying non-stereotypical children’s literature about Blacks and Black experiences. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Philippians 4:13 New Living Translation (NLT) ”For I can do everything through Christ,[a] who gives me strength.” I thank GOD who is my Everything. -

The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States, by Benjamin Brawley

Rights for this book: Public domain in the USA. This edition is published by Project Gutenberg. Originally issued by Project Gutenberg on 2011-01-25. To support the work of Project Gutenberg, visit their Donation Page. This free ebook has been produced by GITenberg, a program of the Free Ebook Foundation. If you have corrections or improvements to make to this ebook, or you want to use the source files for this ebook, visit the book's github repository. You can support the work of the Free Ebook Foundation at their Contributors Page. The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States, by Benjamin Brawley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States Author: Benjamin Brawley Release Date: January 25, 2011 [EBook #35063] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NEGRO IN LITERATURE AND ARTS *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Gary Rees and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.) THE NEGRO IN LITERATURE AND ART © MARY DALE CLARK & CHARLES JAMES FOX CHARLES S. GILPIN AS "THE EMPEROR JONES" The Negro in Literature and Art in the United States BY BENJAMIN BRAWLEY Author of "A Short History of the American Negro" REVISED EDITION NEW YORK DUFFIELD & COMPANY 1921 Copyright, 1918, 1921, by DUFFIELD & COMPANY TO MY FATHER EDWARD MACKNIGHT BRAWLEY WITH THANKS FOR SEVERE TEACHING AND STIMULATING CRITICISM CONTENTS CHAP. -

A Journey with Miss Ida B. Wells

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2018 Self-executed dramaturgy : a journey with Miss Ida B. Wells. Sidney Michelle Edwards University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, American Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Sidney Michelle, "Self-executed dramaturgy : a journey with Miss Ida B. Wells." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2956. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2956 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SELF-EXECUTED DRAMATURGY: A JOURNEY WITH MISS IDA B. WELLS By Sidney Michelle Edwards B.F.A., William Peace University, 2013 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Louisville in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Theatre Arts Department of Theatre Arts University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2018 Copyright, 2018 by Sidney Michelle Edwards ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SELF-EXECUTED DRAMATURGY: A JOURNEY WITH MISS IDA B. WELLS By Sidney Michelle Edwards B.F.A., William Peace University, 2013 Certification Approval on April 12, 2018 By the following Thesis Committee: __________________________________ Thesis Director, Johnny Jones ___________________________________ Dr. -

Patrick Valentine Mollie Huston Lee: Founder of Raleigh’S Public Black Library North Carolina Libraries 56, No 1, Spring 1998, Pp

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarShip Patrick Valentine Mollie Huston Lee: Founder of Raleigh’s Public Black Library North Carolina Libraries 56, no 1, Spring 1998, pp. 23-6 Mollie Lee “talked of her library as though it was a living entity of vast importance.” -- W. E. B. DuBois(FN1) As children “we went religiously to the Richard B. Harrison Library.” -- Audrey V. Wall(FN2) Mollie H. Huston Lee was an energetic apostle for libraries and for her race at a time and place that gave little respect to either. Whatever her personal feelings may have been, she knew how to work within the existing power structure to bring libraries and their treasures to her people. Her great achievement lay in developing, maintaining, and increasing public library service to the African American people of Raleigh and Wake County while never losing the dream of ensuring equal library service for everyone. When people would not come to the library, she took a “market basket in hand” and brought books to them—and more.(FN3) The esteem in which she was held later in life is indicated by her selection as an UNESCO library delegate and her appointment as a trustee of the State Library of North Carolina.(FN4) Although public library service was extended to Blacks in Charlotte in 1905, Raleigh had to wait another thirty years.(FN5) No documentation appears to exist today that can explain the long delay—there were twelve Black public libraries in operation across the state by 1935(FN6) -- but White resistance, including that of librarians, was largely to blame. -

African-American Activist Mary Church Terrell and the Brownsville Disturbance Debra Newman Ham Morgan State University

Trotter Review Volume 18 Article 5 Issue 1 Niagara, NAACP, and Now 1-1-2009 African-American Activist Mary Church Terrell and the Brownsville Disturbance Debra Newman Ham Morgan State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Ham, Debra Newman (2009) "African-American Activist Mary Church Terrell and the Brownsville Disturbance," Trotter Review: Vol. 18: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_review/vol18/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the William Monroe Trotter Institute at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Trotter Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bibliography THE TROTTER REVIEW Christian, Garna L. Black Soldiers in Jim Crow Texas 1899–1917. College African-American Activist Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1995. Offers a concise view of the raid and controversy and first description of the unsolved shooting of Captain Macklin at Fort Reno. Mary Church Terrell Lane, Ann J. The Brownsville Affair: National Crisis and Black Reaction. and the Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press, 1971. Examines the raid and aftermath in detail. Like Christian, she does not assess guilt, but criticizes Brownsville Disturbance Roosevelt for denying the soldiers due process. Tinsley, James A. “Roosevelt, Foraker, and the Brownsville Affray.” Journal of Negro History 41 (January, 1956), 43–65. Revives the controversy in a Debra Newman Ham scholarly forum after decades of neglect. -

Received by the Regents February 20, 2020

The University of Michigan Office of Development Unit Report of Gifts Received 4 Year Report as of December 31, 2019 Transactions Dollars Fiscal Year Ended June 30, Fiscal Fiscal Fiscal Year Ended June 30, Fiscal Fiscal YTD YTD YTD YTD Unit 2017 2018 2019 December 31, 2018 December 31, 2019 2017 2018 2019 December 31, 2018 December 31, 2019 A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning 890 785 834 469 474 4,761,133 6,664,328 4,858,713 3,905,392 4,367,777 Penny W. Stamps School of Art and Design 565 644 615 366 348 2,052,654 2,133,117 1,795,126 1,236,963 1,466,436 Stephen M. Ross School of Business 8,418 7,897 7,610 4,332 3,801 32,333,848 31,703,408 41,662,544 26,456,778 20,994,441 School of Dentistry 1,822 1,782 1,920 980 896 6,492,684 4,201,101 3,080,617 1,618,436 1,780,580 School of Education 2,412 2,336 2,557 1,375 1,620 5,938,803 8,474,970 11,298,726 4,507,986 3,578,827 College of Engineering 7,961 7,321 7,459 4,051 3,983 29,135,173 33,935,813 31,682,539 17,337,173 12,892,451 School for Environment and Sustainability 929 900 918 501 556 2,691,334 4,469,385 2,220,414 1,433,307 3,301,149 Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies 2,935 2,508 2,617 1,456 1,400 5,531,888 5,010,647 6,083,214 4,218,373 1,010,695 School of Information 1,328 1,446 1,345 757 706 921,261 1,189,629 3,412,544 2,459,072 670,461 School of Kinesiology 975 1,016 988 525 539 1,361,012 1,014,328 1,394,594 460,816 842,877 Law School 5,984 5,800 5,588 2,967 2,972 14,320,487 24,615,924 12,771,100 7,008,304 8,169,805 College of Literature, Science, and the Arts 17,344 17,407 19,014 10,787 10,625 49,141,904 44,983,558 57,532,052 35,592,264 20,851,552 School of Music, Theatre & Dance 4,583 5,221 4,293 2,632 2,440 8,149,703 6,950,036 10,541,563 5,044,782 3,677,925 School of Nursing 1,695 1,693 1,728 972 859 2,891,012 2,638,340 2,999,712 1,589,844 1,764,274 College of Pharmacy 1,097 1,035 984 521 502 3,273,265 3,451,305 1,945,261 1,230,664 1,207,111 School of Public Health 1,735 1,738 1,760 965 980 7,688,432 11,536,036 4,915,632 1,979,543 1,326,949 Gerald R. -

Capa Oficial

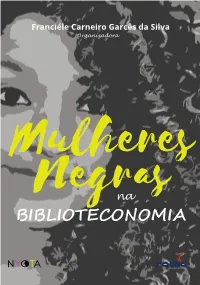

Franciéle Carneiro Garcês da Silva Organizadora Mulheres Negrasna BIBLIOTECONOMIA NYOTA soluções gráficas Franciéle Carneiro Garcês da Silva Organizadora MULHERES NEGRAS NA BIBLIOTECONOMIA Florianópolis, SC Rocha Gráfica e Editora Ltda. 2019 Nyota Coordenação do Selo Franciéle Carneiro Garcês da Silva Nathália Lima Romeiro Site: https://www.nyota.com.br/ Comitê Científico Andreia Sousa da Silva (UDESC) Priscila Sena (UFSC) Daniella Camara Pizarro (UDESC) Gláucia Aparecida Vaz (UFMG) Dirnéle Carneiro Garcez (UFSC) Graziela dos Santos Lima (UNESP) Nathália Lima Romeiro (UFMG) Andreza Gonçalves (UFMG) Bruno Almeida (UFBA) Erinaldo Dias Valério (UFG) Diagramação: Franciéle Carneiro Garcês da Silva Arte da Capa: Dirnéle Carneiro Garcez, Franciéle Carneiro Garcês da Silva. Revisão textual: Pedro Giovâni da Silva Ficha Catalográfica: Priscila Rufino Fevrier – CRB 7-6678 M958 Mulheres negras na Biblioteconomia / Franciéle Carneiro Garcês da Silva (Org.) - Florianópolis, SC: Rocha Gráfica e Editora, 2019. (Selo Nyota) 339 p. Inclui Bibliografia. Disponível em: <https://www.nyota.com.br/>. ISBN 978-85-60527-07-6 (e-book) ISBN 978-85-60527-06-9 (impresso) 1. Biblioteconomia. 2. Mulheres negras. 3. Biblioteconomia Negra. I. Silva, Franciéle Carneiro Garcês da. VI. Título. ESSA OBRA É LICENCIADA POR UMA LICENÇA CREATIVE COMMONS Atribuição – Uso Não Comercial – Compartilhamento pela mesma licença 3.0 Brasil1 É permitido: Copiar, distribuir, exibir e executar a obra Criar obras derivadas Condições: ATRIBUIÇÃO Você deve dar o crédito apropriado ao(s) autor(es) ou à(s) autora(s) de cada capítulo e às organizadoras da obra. NÃO-COMERCIAL Você não pode usar esta obra para fins comerciais. COMPARTILHAMENTO POR MESMA LICENÇA Se você remixar, transformar ou criar a partir desta obra, tem de distribuir as suas contribuições sob a mesma licença2 que este original.