Appendix Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oriental and Pacific Boxing Federation OPBF Male May Ratings 2016

Oriental and Pacific Boxing Federation OPBF Male May Ratings 2016 Minimumweight (105 lbs. / 47.627 kgs) Light Flyweight (108 lbs. / 48.988 kgs) Flyweight (112 lbs. / 50.802 kgs) Champion Chao Zhong Xiong (C ) Champion VACANT Champion Arden Diale (P) Won date September 18, 2015 Won date Won date December 2, 2015 Last defense Last defense Last defense February 20, 2016 (1st def) Silver C. Riku Kano (J) Silver C. Silver C. 1 Merlito Sabillo (P) 1 Ken Shiro (J) 1 Kwanpichit "Express" (T) 2 Ryuya Yamanaka (J) 2 Toshimasa Ouchi (J) 2 Takuya Kogawa (J) 3 Jeronil Borres (P) 3 Cristian Araneta (P) 3 Kongfah Nakornluang (T) 4 Tatsuya Fukuhara (J) 4 Sho Kimura (J) 4 Eaktawan Krungthepthonburi (T) 5 Dexter Alimento (P) 5 Takuro Habu (J) 5 Daigo Higa (J) 6 Genki Hanai (J) 6 Rene Patillano (P) 6 Naoki Mochizuki (J) 7 Jerry Tomogdan (P) 7 Michael Landero (P) 7 Shun Kosaka (J) 8 Petchmanee Kokietgym (T) 8 Detranong Omkrathonk (T) 8 Masahiro Sakamoto (J) 9 Clyde Azarcon (P) 9 Richard Claveras (P) 9 Pablo Carillo (J/ Co) 10 Hiroto Kyoguchi (J) 10 Ben Mananquil (P) 10 Renan Trongco (P) 11 Lito Dante (P) 11 Masataka Taniguchi (J) 11 Marjun Pantilgan (P) 12 Rommel Asenjo (P) 12 Koji Itagaki (J) 12 Pakpoom Hammarach (T) 13 Jeffrey Galero (P) 13 Yu Kimura (J) 13 Masayoshi Hashizume (J) 14 Reiya Konishi (J) 14 Kenichi Horikawa (J) 14 Jay-Ar Diama (P) 15 Roque Lauro (P) 15 Renren Tesorio (P) 15 Giovanni Escaner (P) Super-Flyweight (115 lbs. / 52.163 kgs) Bantamweight (118 lbs / 53.524 kgs) Super-Bantamweight(122 lbs / 55.338 kgs) Champion Takuma Inoue (J) Champion Takahiro Yamamoto (J) Champion Shun Kubo (J) Won date July 6, 2015 Won date August 2, 2015 Won date December 26, 2015 Last defense May 8, 2016 (2nd def.) Last defense December 31, 2015 (1st def.) Last defense May 16, 2016 (1st Def.) Silver C. -

Hennessy Sports Worldwide Ltd, 150 High Street, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN13 1XE England Tel: + 44 (0) 203 146 6000 Office Email: Mick@

150 High Street Sevenoaks Kent TN13 1XE Francisco Valcarcel, President World Boxing Organization 1056 Munoz Rivera Avenue San Juan 00927 Puerto Rico BY EMAIL 6 October 2017 Dear President Valcarcel Notice of Complaint WBO Heavyweight Championship – Joseph Parker v Hughie Fury – 23 September 2017 Please accept this letter as a Complaint submitted to you as President of the WBO pursuant to Article 3 of the WBO Appeal Regulations. The Complainants and interested parties are: Boxer Hughie Lewis Fury Address Hollybank Park, Warburton Bridge Road, Rixton, Warrington WA3 6HC Domicile England Nationality British Telephone Number 07788 874 788 Email Address [email protected] Mailing Address As above Hennessy Sports Worldwide Ltd, 150 High Street, Sevenoaks, Kent, TN13 1XE England Tel: + 44 (0) 203 146 6000 Office Email: [email protected] www.hennessysports.com Promoter Mick Hennessy of Hennessy Sports Worldwide Limited Address 150 High Street, Sevenoaks, Kent TN13 1XE Domicile England Nationality British Telephone Number 0203 146 6050 Email Address [email protected] Mailing Address As above The Complainants and interested parties as referred to above are the challenger and promoter of the WBO World Heavyweight Championship bout that took place at the Manchester Arena on Saturday 23 September 2017. You may consider that Joseph Parker and Duco Promotions Limited are also interested parties. The Complainants consider that the scoring of two of the judges of the bout, John Madfis and Terry O’Connor, do not properly or correctly reflect the contest that took place during the above mentioned bout. Both judges scored the contest in favour of Joseph Parker by 118 to 110 points as compared to the other judge, Rocky Young, who scored the bout as a draw at 114 each (which we still consider to be extremely generous towards Joseph Parker). -

Surname Index to Volumes 1-20 the Colorado Genealogist

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Surname Index to Volumes 1-20 The Colorado Genealogist ©2009 Colorado Genealogical Society Surname Index for Volumes 1-20 Introduction ! This index was scanned and OCR technology used on the original indexes published by the Colorado Genealogical Society. Every attempt has been made to obtain an accurate “reading” of the information. There may still be errors in the transfer. All of the original indexes used the spellings that appeared in the original quarterly publications, some of which may have contained spelling or typographical errors. A prudent searcher will try various spellings of the surnames being searched. ! The index for volumes 1-20 put one surname at the beginning of the listing of alphabetical first names. In transferring this index to searchable pdf, some additional surnames were added for names covering more than 1 column or page. ! Searching Hints •This is a searchable pdf document and uses the same searching tools you would find in your pdf reader, such as Adobe Acrobat Reader. ! •Begin by typing in a surname only. You may have to search on a page for the given name, like you would in a printed index. Where there was more than a column of a surname, some additional surnames were added in. ! •If there are too many “hits” from surname only, then type surname, first name. !That is how it will appear in the index if there are too many of a single surname. •If the surname has a prefix such as “de,” “le” or “van” try entering both with and ! without spaces between names. There are entries in either style.! ©2009 Colorado Genealogical Society Surname Index for Volumes 1-20 of The Colorado Genealogist ABBEY, A. -

Men's Athlete Profiles 1 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON

Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games - Men's Athlete Profiles 49KG – SIMPLICE FOTSALA – CAMEROON (CMR) Date Of Birth : 09/05/1989 Place Of Birth : Yaoundé Height : 160cm Residence : Region du Centre 2018 – Indian Open Boxing Tournament (New Delhi, IND) 5th place – 49KG Lost to Amit Panghal (IND) 5:0 in the quarter-final; Won against Muhammad Fuad Bin Mohamed Redzuan (MAS) 5:0 in the first preliminary round 2017 – AFBC African Confederation Boxing Championships (Brazzaville, CGO) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Matias Hamunyela (NAM) 5:0 in the final; Won against Mohamed Yassine Touareg (ALG) 5:0 in the semi- final; Won against Said Bounkoult (MAR) 3:1 in the quarter-final 2016 – Rio 2016 Olympic Games (Rio de Janeiro, BRA) participant – 49KG Lost to Galal Yafai (ENG) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2016 – Nikolay Manger Memorial Tournament (Kherson, UKR) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Ievgen Ovsiannikov (UKR) 2:1 in the final 2016 – AIBA African Olympic Qualification Event (Yaoundé, CMR) 1st place – 49KG Won against Matias Hamunyela (NAM) WO in the final; Won against Peter Mungai Warui (KEN) 2:1 in the semi-final; Won against Zoheir Toudjine (ALG) 3:0 in the quarter-final; Won against David De Pina (CPV) 3:0 in the first preliminary round 2015 – African Zone 3 Championships (Libreville, GAB) 2nd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the final 2014 – Dixiades Games (Yaounde, CMR) 3rd place – 49KG Lost to Marcus Edou Ngoua (GAB) 3:0 in the semi- final 2014 – Cameroon Regional Tournament 1st place – 49KG Won against Tchouta Bianda (CMR) -

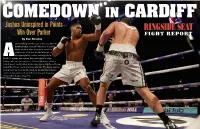

Joshua Uninspired in Points Win Over Parker FIGHT REPORT by Don Stradley

Joshua Uninspired in Points Win Over Parker FIGHT REPORT By Don Stradley nyone walking into the press conference after the Anthony Joshua –Joseph Parker bout in Cardiff, Wales would’ve been shocked by the mood of the room. It felt less like the aftermath of a heavyweight title contest, and more like a Abunch of grumpy men waiting their turn before a judge. Joshua, who won a unanimous 12-round decision, smiled a lot but wasn’t exactly elated. Parker, who looked slightly scuffed up around the left eye, could only shrug and say, “The bigger and bet- ter man won.” As for going 12 rounds for the first time in his pro career, Joshua said he felt good. More smiling and shrugging followed this. It was a shrug fest. y winning, Joshua added another alphabet title to his was focused. I controlled him behind the jab, and the main collection – he has three now – and he said he wants thing is I am the unified champion of the world. I thought it all the belts because it would make him “the most was hard, but going the 12 rounds was light work.” powerful man at the table,” a reference, perhaps, to It was a scrappy bout. Parker used his own jab to keep BDeontay Wilder, the American heavyweight who also owns a things close during the early part of the fight, but by the mid- title belt. Though Joshua and Parker had inspired 78,000 cus- dle rounds it appeared Joshua was landing more often. Parker tomers to crowd into Principality Stadium, Wilder was on the dashed in and out, doing what shorter fighters are supposed minds of many. -

Bruce George Pale Sauni

Skills Highway Workplace Literacy and Numeracy Forum Waipuna Conference Centre, Auckland 2016 Bruce George Pale Sauni Collabora've Project between AKO Aotearoa and Literacy Aotearoa He Taunga Waka BeMer Engagement for Maori and Pasifika Learners Confidence, Competence, Effecve Engagement Founder of the Progressive Educa'on Movement Educaon is a Social process Educaon is growth Educaon is, not a preparaon for life Educaon is life Andragogy is the art and science of adult learning, thus refers to any form of adult learning Which is based on several assumpons Uses the experience and prior knowledge of the learner to par'cipate in ac'vies Integral is the self-identy of the learner. This self-identy is also important in terms of their culture The adult learner learns best when new informaon is presented in a real-life context Paulo Freire’s Cri'cal Literacy (1921-1997) Transformaons of economic and social condions The uses of the students’ own language and culture are important components Developing the learners’ thinking process He Taunga Waka Whanaungatanga-Akaa’a: Connecon, blood relaon Ako-Api’i: To learn, to teach Aro-Akamanako: Reflec've Prac'ce A posi've learning rela'onship based on mutual respect of one’s cultural capital, language and cultural values That first contact is very important it can set up barriers or bring them down Ako : Api’i The learner can become the teacher and vice versa. When this happens the learner’s self-esteem increases and their cultural capital and world view is acknowledged. Reflec've prac'ce (Ac'on + Reflec'on -

Notre Dame Alumnus, Vol. 36, No. 05 -- August-September 1958

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus NOTRE OAME AUG 13 1958 Vol. 36 • No. 5 nUMANITIES LIBRARY Aiig. - Sept. 1958 James E. Armstrong, '25 Editor Exqiiisite receptacle for relic of St Bemadette, inspired by Gold en Dome and sent by Notre Dam 3 \ John F. Laughlin, '48 Club of Borne to Lourdes Confra ternity on campus (see story: Managing Editor "NJ). Club of Eternal City"). ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: • Chapter Two of "U.N.D. .. Night, 1958"- • Rundown on a Record Reunion • Commencement Addresses, Highlights • Presenting the Class of '58 DEATH TAKES DEAN McCARTHY. ALUMNI ASSOCIATION PROFESSOR FRANK J. SKEELER BOARD OF DIRECTORS Officers In tlie past few months death has of Income of Indiana Corporations. J. PATRICK CANNY, '28 Honorary President claimed two men who together ser\'ed Dean McCarthy was bom in Holy- pRiVNCis L. LA^-DEN, '36 President ; the University for more than fifty years. oke, Mass., in 1896. In 1927 he mar EDMO.XD R. HACGAB, '38 James E. McCarthy, dean of the ried Dorotliy Hoban in Chicago. Mrs. Club Vice-President College of Commerce for 32 years, died McCarthy survives, as do three sons,- EUGENE M. KENNEDY, '22 July 11 in Presbyterian Hospital, Chi Edward D., '50; James B., '49, and Class Vice-President *• cago, after a verj* brief illness. Kevin; a daughter, two brothers, a OSCAR J. DORWIN, '17 Mr. McCarthy was appointed Dean sister and eight grandchildren. : : .. Fund Vice-President * Emeritus of Notre Dame October 11, Requiem Mass was celebrated July JAMES E. -

July 2020 HEAVYWEIGHT

July 2020 HEAVYWEIGHT Champion: Anthony Joshua (23-1)- UK- Won a 12-round decision over Andy Ruiz, Jr. (33-1) on Dec. 7, 2019. KO’ed by new champion Andy Ruiz, Jr. in the seventh round on Jun. 1, 2019. 1- Oleksandr Usyk (16-0) –RUS- Won a 12-round bout over Chazz Witherspoon (38-3) on Oct. 12, 2019. Requested to be the mandatory challenger in the Heavyweight division. Section 14. Super Champion. (d) PRIVILEGES AFFORDED SUPER CHAMPIONS. (2) Eligibility to be considered for designation as the mandatory challenger in higher or lower division. If requested by a Super Champion, the Championship Committee may designate the Super Champion as the mandatory challenger for the immediate higher or lower division. The Championship Committee granted Mr. Usyk petition on June 22, 2019. 2- Joseph Parker (26-2)-NZ- TKO’ed Alex Leapai (32-7-4) in the tenth round on Jun. 29, 2019. 3- Daniel Dubois (13-0)-UK- International. KO’ed a classified boxer Kyotaro Fujimoto (21-1) in the second round on Dec. 21, 2019. TKO’ed a classified boxer Ebenezer Tetteh (19-0) in the first round on Sep. 27, 2019. KO’ed Nathan Gorman (16-0) in the fifth round on Jul. 13, 2019. 4- Kubrat Pulev (28-1) – BUL- Won a 10-round bout over Rydell booker (26-2) on Nov. 9, 2019. 5- Andy Ruiz, Jr. (33-1)-USA. Lost a 12-round decision against Anthony Joshua on Dec. 7, 2019. TKO’ed the champion Anthony Joshua (22-0) in the seventh round on June 1, 2019. -

Ranking As of July 14, 2014

Ranking as of July 14, 2014 HEAVYWEIGHT JR. HEAVYWEIGHT LT. HEAVYWEIGHT (Over 201 lbs.)(Over 91,17 kgs) (200 lbs.)(90,72 kgs) (175 lbs.)(79,38 kgs) CHAMPION CHAMPION CHAMPION WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO (Sup Champ UKR MARCO HUCK GER SERGEY KOVALEV RUS 1. Dereck Chisora (International) UK 1. Krzysztof Glowacki (Int-Cont) POL 1. Jean Pascal HAI 2. Andy Ruiz (Int-Cont) USA 2. Vikapita Meroro NAM 2. Eleider Alvarez COL 3. Deontay Wilder USA 3. Nuri Seferi (WBO Europe) MAC 3. Robin Krasniqi (International) GER 4. Tyson Fury UK 4. Grigory Drozd RUS 4. Thomas Williams, Jr. (NABO) USA 5. Christian Hammer ROM 5. Tony Bellew (International) UK 5. Erik Skoglund SWD 6. Kubrat Pulev BUL 6. Nathan Cleverly UK 6. Dmitry Sukhotsky RUS 7. Charles Martin (NABO) USA 7. Jean Marc Mormeck FRA 7. Isidro Ranoni Prieto (Latino) PAR 8. David Price UK 8. Ilunga Makabu SA 8. Dominic Böesel (Inter-Continental) GER 9. Mike Perez CUB 9. Felix Cora, Jr. (Latino) ARG 9. Robert Berridge (Oriental) NZ 10. Bryant Jennings USA 10. Thabiso Mchunu SA 10. Blake Caparello AUST 11. Francesco Pianeta (WBO Europe ITA 11. Chad Dawson USA 11. Nadjib Mohammedi FRA 12. Alexander Povetkin RUS 12. Mirko Larghetti ITA 12. Isaac Chilemba MAL 13. Vyacheslav Glazkov UKR 13. Pawel Kolodziej POL 13. Enrico Koelling GER 14. Irineu Beato Costa, Jr. (Latino BRA 14. Yunier Dorticos USA 14. Umberto Savigne CUB 15. Joseph Parker (Oriental) NZ 15. David Aloua (Asia-Pacific) NZ 15. Oleksandr Cherviak UKR **Noel Gevor (WBO Youth) ARM ** Umar Salamov (WBO Youth) RUS CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS CHAMPIONS WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO WBA DENNIS LEBEDEV WBA BERNARD HOPKINS WBA WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO IBF YOAN PABLO HERNANDEZ IBF BERNARD HOPKINS IBF BERMANE STIVERNE WBC KRZYSZTOF WLODARCZYK WBC ADONIS STEVENSON WBC SUP. -

Report of Gifts, It Is Clear That the Mission of Holy Cross Is Recognized and Appreciated in Heartfelt and Tangible Ways by Its Alumni, Parents, Students and Friends

COLLEGE OF THE HOLY CROSS Report2012 of Gifts TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights of the Year 4 The Holy Cross Fund 6 Honor Roll of Donors 12 Parent Giving 64 Honor Roll of Friends 71 Corporate and Foundation Giving 75 Front and back cover photos by John Gillooly MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT New plans stand on a firm foundation Holy Cross is celebrating a year of impressive dedication and generosity. Contributions to the College made history with a record-breaking 17,227 alumni donors. In recognition of their love and enthusiasm for Holy Cross, 55.2 percent of our alumni made a gift to the College. This achievement keeps Holy Cross among a very small and elite group of colleges and universities that can claim such extraordinary alumni support. An anonymous donor provided a $1 million challenge gift in recognition of this goal, contributing to a total of $22.9 million in donations. In addition, we saw tremendous attendance at our annual dinner of the Holy Cross Leadership Council of New York, where we honored alumnus Stan Grayson ’72. Such devotion has helped make Holy Cross the premier Jesuit liberal arts college in America. In my first few months as president, I have been deeply moved by our caring and enthusiastic Holy Cross community. Our year-end statistics are impressive by any measure, upholding our reputation as one of the country’s most-loved colleges, based on our alumni giving rate. In this Report of Gifts, it is clear that the mission of Holy Cross is recognized and appreciated in heartfelt and tangible ways by its alumni, parents, students and friends. -

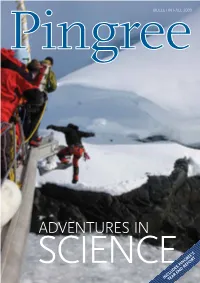

Adventures In

BULLETIN Fall 2009 adventurEs in sCIENCE Ingree’sPort IncludesYear end P re board of trustees 2008–09 Jane Blake Riley ’77, p ’05 President contents James D. Smeallie p ’05, ’09 V ice President Keith C. Shaughnessy p ’04, ’08, ’10 T reasurer Philip G. Lake ’85 4 Pingree Secretary athletes Thanks Anthony G.L. Blackman p ’10 receive Interim Head of School All-American Nina Sacharuk Anderson ’77, p ’09 ’11 honors for stepping up to the plate. Kirk C. Bishop p ’06, ’06, ’08 Tamie Thompson Burke ’76, p ’09 Patricia Castraberti p ’08 7 Malcolm Coates p ’01 Honoring Therese Melden p ’09, ’11 Reflections: Science Teacher Even in our staggering economy, Theodore E. Ober p ’12 from Head of School Eva Sacharuk 16 Oliver Parker p ’06, ’08, ’12 Dr. Timothy M. Johnson Jagruti R. Patel ’84 you helped the 2008–2009 Pingree William L. Pingree p ’04, ’08 3 Mary Puma p ’05, ’07, ’10 annual Fund hit a home run. Leslie Reichert p ’02, ’07 Patrick T. Ryan p ’12 William K. Ryan ’96 Binkley C. Shorts p ’95, ’00 • $632,000 raised Joyce W. Swagerty • 100% Faculty and staff participation Richard D. Tadler p ’09 William J. Whelan, Jr. p ’07, ’11 • 100% Board of trustees participation Sandra Williamson p ’08, ’09, ’10 Brucie B. Wright Guess Who! • 100% class of 2009 participation Pictures from Amy McGowan p ’07, ’10 the archives 26 • 100% alumni leadership Board participation Parents Association President William K. Ryan ’96 • 15% more donations than 2007–2008 A Lumni L eadership Board President Cover Story: • 251 new Pingree donors board of overseers Adventures in Science Alice Blodgett p ’78, ’81, ’82 Susan B. -

Male August Ratings 2015

Oriental and Pacific Boxing Federation OPBF Male August Ratings 2015 Minimumweight (105 lbs. / 47.627 kgs) Light Flyweight (108 lbs. / 48.988 kgs) Flyweight (112 lbs. / 50.802 kgs) Champion VACANT Champion Jonathan Taconing Champion Koki Eto Won date Won date March 25, 2014 Won date June 17, 2014 Last defense Last defense Last defense June 8, 2015 (2nd def.) Man.def.due Man.def.due Man.def.due 1 Xiong Zhao Zhong (C ) 1 Richard Claveras (P) 1 Arden Diale (P) 2 Crison Omayao (P) 2 Yu Kimura (J) 2 Myung-Ho Lee (J) 3 Rommel Asenjo (P) 3 Kenichi Horikawa (J) 3 Kwanpichit "Express" (T) 4 Merlito Sabillo (P) 4 Michael Enriquez (P) 4 Takuya Kogawa (J) 5 Rolly Sumalpong (P) 5 Renren Tesorio (P) 5 Giovanni Escaner (P) 6 Roque Lauro (P) 6 Ken Shiro (J) 6 Renoel Pael (P) 7 Ryuya Yamanaka (J) 7 Rene Patillano (P) 7 Macrea Gandionco (P) 8 Jessie Espinas (P) 8 Jason Manigos Canoy (P) 8 Renan Trongco (P) 9 Takumi Sakae (J) 9 Koji Itagaki (J) 9 Cyborg Nawatedani (J) 10 Jeffrey Galero (P) 10 Atsushi Kakutani (J) 10 Kongfah Nakornluang (T) 11 Tatsuya Fukuhara (J) 11 Toshimasa Ouchi (J) 11 Masayuki Kuroda (J) 12 Ryuji Hara (J) 12 Virgilio Silvano (P) 12 Tetsuma Hayashi (J) 13 Go Odaira (J) 13 Jomar Fajardo (P) 13 Yuki Fukimoto (J) 14 Reiya Konishi (J) 14 Ben Mananquil (P) 14 Fernando Lumacad (P) 15 Genki Hanai (J) 15 Lionel Legada (P) 15 Rommel Oliveros (P) Super-Flyweight (115 lbs. / 52.163 kgs) Bantamweight (118 lbs / 53.524 kgs) Super-Bantamweight(122 lbs / 55.338 kgs) Champion Takuma Inoue (J) Champion Takahiro Yamamoto (J) Champion Shingo Wake Won date July 6, 2015 Won date August 2, 2015 Won date March 10 2013 Last defense Last defense Last defense Feb.