Onl Er Exd 712 1..18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Very Rare Case of Dissecting Cellulitis of the Scalp in an Indonesian Man

A Very Rare Case of Dissecting Cellulitis of the Scalp in an Indonesian Man Rizky Lendl Prayogo1, Lusiana1, Sri Linuwih Menaldi1, Sondang P. Sirait1, Eliza Miranda1 1Department of Dermatology and Venereology Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia / Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo National General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia Keywords: dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, dissecting folliculitis, follicular occlusion tetrad, diagnosis, isotretinoin Abstract: Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp (DCS), also known as dissecting folliculitis, perifolliculitis capitis abscedens et suffodiens (PCAS), or Hoffman’s disease, is a primary neutrophilic cicatricial alopecia without clear etiology. Along with hidradenitis suppurativa, acne conglobata, and pilonidal cyst, they were recognized as ‘follicular occlusion tetrad’. A 43-year-old Indonesian man presented to our department with four years history of persistent, slightly painful subcutaneous nodules, abscesses, and sinuses that discharged purulent exudate on vertex and occipital scalp. There was also associated patchy alopecia. He had severe acne during his adolescence to early adulthood. Trichoscopic evaluation showed yellowish and whitish area lacking of follicular openings. Histopathological examination showed follicular occlusion, dilatation, and rupture with mixed inflammatory infiltrates, mainly neutrophils. The diagnosis of DCS was confirmed by clinical, trichoscopic, and histopathological examinations. Isotretinoin 20 mg daily was given to normalize the follicular keratinization. Considering its very rare occurrence in an Indonesia man, this case was reported to emphasize the diagnosis of DCS. 1 INTRODUCTION should be considered (Otberg & Shapiro, 2012; Scheinfeld, 2014). Considering its low prevalence in DCS, also known as dissecting folliculitis, PCAS, Indonesia, we are intrigued to report a case or Hoffmann’s disease, is a very rare primary emphasizing the diagnosis of DCS. -

Differential Diagnosis of the Scalp Hair Folliculitis

Acta Clin Croat 2011; 50:395-402 Review DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF THE SCALP HAIR FOLLICULITIS Liborija Lugović-Mihić1, Freja Barišić2, Vedrana Bulat1, Marija Buljan1, Mirna Šitum1, Lada Bradić1 and Josip Mihić3 1University Department of Dermatovenereology, 2University Department of Ophthalmology, Sestre milosrdnice University Hospital Center, Zagreb; 3Department of Neurosurgery, Dr Josip Benčević General Hospital, Slavonski Brod, Croatia SUMMARY – Scalp hair folliculitis is a relatively common condition in dermatological practice and a major diagnostic and therapeutic challenge due to the lack of exact guidelines. Generally, inflammatory diseases of the pilosebaceous follicle of the scalp most often manifest as folliculitis. There are numerous infective agents that may cause folliculitis, including bacteria, viruses and fungi, as well as many noninfective causes. Several noninfectious diseases may present as scalp hair folli- culitis, such as folliculitis decalvans capillitii, perifolliculitis capitis abscendens et suffodiens, erosive pustular dermatitis, lichen planopilaris, eosinophilic pustular folliculitis, etc. The classification of folliculitis is both confusing and controversial. There are many different forms of folliculitis and se- veral classifications. According to the considerable variability of histologic findings, there are three groups of folliculitis: infectious folliculitis, noninfectious folliculitis and perifolliculitis. The diagno- sis of folliculitis occasionally requires histologic confirmation and cannot be based -

A Deep Learning System for Differential Diagnosis of Skin Diseases

A deep learning system for differential diagnosis of skin diseases 1 1 1 1 1 1,2 † Yuan Liu , Ayush Jain , Clara Eng , David H. Way , Kang Lee , Peggy Bui , Kimberly Kanada , ‡ 1 1 1 Guilherme de Oliveira Marinho , Jessica Gallegos , Sara Gabriele , Vishakha Gupta , Nalini 1,3,§ 1 4 1 1 Singh , Vivek Natarajan , Rainer Hofmann-Wellenhof , Greg S. Corrado , Lily H. Peng , Dale 1 1 † 1, 1, 1, R. Webster , Dennis Ai , Susan Huang , Yun Liu * , R. Carter Dunn * *, David Coz * * Affiliations: 1 G oogle Health, Palo Alto, CA, USA 2 U niversity of California, San Francisco, CA, USA 3 M assachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA 4 M edical University of Graz, Graz, Austria † W ork done at Google Health via Advanced Clinical. ‡ W ork done at Google Health via Adecco Staffing. § W ork done at Google Health. *Corresponding author: [email protected] **These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract Skin and subcutaneous conditions affect an estimated 1.9 billion people at any given time and remain the fourth leading cause of non-fatal disease burden worldwide. Access to dermatology care is limited due to a shortage of dermatologists, causing long wait times and leading patients to seek dermatologic care from general practitioners. However, the diagnostic accuracy of general practitioners has been reported to be only 0.24-0.70 (compared to 0.77-0.96 for dermatologists), resulting in over- and under-referrals, delays in care, and errors in diagnosis and treatment. In this paper, we developed a deep learning system (DLS) to provide a differential diagnosis of skin conditions for clinical cases (skin photographs and associated medical histories). -

Alopecia with Perifollicular Papules and Pustules

Tyler A. Moss, DO; Thomas M. Alopecia with perifollicular Beachkofsky, MD; Samuel F. Almquist, MD; Oliver J. Wisco, DO; papules and pustules Michael R. Murchland, MD A.T. Still University, Our 23-year-old patient thought his hair loss was Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine, probably “genetic.” But that didn’t explain the painful Kirksville, Mo (Dr. Moss); Kunsan AB, Republic of pustules. Korea (Dr. Beachkofsky); Wilford Hall Medical Center, Lackland AFB, Tex (Drs. Almquist, Wisco, and Murchland) A 23-year-old African American man Physical examination revealed multiple sought care at our medical center because perifollicular papules and pustules on the [email protected] he had been losing hair over the vertex of his vertex of his scalp with interspersed patches DEPARTMENT EDITOR scalp for the past several years. He indicated of alopecia (FIGURE 1). Th ere were no lesions Richard P. Usatine, MD that his father had early-onset male patterned elsewhere on his body and his past medical University of Texas Health alopecia. As a result, he considered his hair history was otherwise unremarkable. Science Center at San Antonio loss “genetic.” However, he described waxing and waning fl ares of painful pustules associ- ● The authors reported no WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS? potential confl ict of interest ated with occasional spontaneous bleeding relevant to this article. and discharge of purulent material that oc- ● HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE curred in the same area as the hair loss. THIS PATIENT? FIGURE 1 Alopecia with a painful twist A B PHOTOS COURTESY OF: OLIVER J. WISCO, DO PHOTOS COURTESY This 23-year-old patient said that he had spontaneous bleeding and discharge of purulent material in the area of his hair loss. -

Dissecting Cellulitis of the Scalp Treated with Rifampicin and Isotretinoin: Case Reports

Dissecting Cellulitis of the Scalp Treated With Rifampicin and Isotretinoin: Case Reports Sofia Georgala, MD, PhD; Chrysovalantis Korfitis, MD; Dikaia Ioannidou, MD; Theodosis Alestas, MD; Georgios Kylafis, MD; Caterina Georgala, MD Dissecting cellulitis of the scalp, or perifolliculitis destruction, and keratinous debris are observed. The capitis abscedens et suffodiens, is an uncom- etiology still remains unclear. Although cultures may mon chronic suppurative disease of the scalp reveal no bacteria, Staphylococcus aureus is occasion- manifested by follicular and perifollicular inflam- ally isolated.1,2 However, follicular hyperkeratosis is matory nodules that suppurate and undermine, thought to play a primary role in the pathogenesis of forming intercommunicating sinuses, and leading dissecting cellulitis of the scalp.3 to scarring alopecia. Treatment generally fails to obtain a permanently successful result; thus, Case Reports many therapeutic options have been proposed. Patient 1—A 24-year-old man presented with a We report 4 cases of dissecting cellulitis of the 2-year history of painful, disseminated, tender nodules scalp successfully treated with oral rifampicin covering the temporal area of the scalp. Many lesions and oral isotretinoin. To our knowledge, this is were inflammatory with purulent discharge. Alopecia the first report of oral rifampicin used concomi- was noted over nodules. The patient reported clinical tantly with oral isotretinoin in this disease entity. worsening after mental and physical stress. He was We also present a brief review of the literature on treated with oral antibiotics, such as clindamycin the topic. hydrochloride and erythromycin, with poor response. Cutis. 2008;82:195-198. Findings from hematologic and biochemical inves- tigation were normal. -

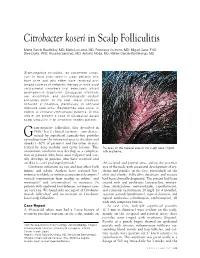

Citrobacter Koseri in Scalp Folliculitis

Citrobacter koseri in Scalp Folliculitis Marta Garcia-Bustinduy, MD; Maria Lecuona, MD; Francisco Guimera, MD; Miguel Saez, PhD; Sara Dorta, PhD; Rosalba Sanchez, MD; Antonio Noda, MD; Rafael Garcia-Montelongo, MD Gram-negative folliculitis, an uncommon condi- tion, is most often seen in older patients who have acne and who either have received pro- longed courses of antibiotic therapy or have used antibacterial cleansers that selectively inhibit gram-positive organisms. Citrobacter infections are uncommon, and dermatologists seldom encounter them. In the past, these infections occurred in hospitals, particularly in neonatal intensive care units. Bacteremias also occur in elderly or immunocompromised patients. In this article, we present a case of Citrobacter koseri scalp folliculitis in an otherwise healthy patient. ram-negative folliculitis, first described in 1968,1 has 2 clinical varieties—one charac- G terized by superficial comedo-free pustules extending from the infranasal area to the chin and cheeks (~80% of patients) and the other charac- terized by deep nodular and cystic lesions. This Pustules on the parietal area of the scalp were ringed uncommon condition may develop as a complica- with erythema. tion in patients who have acne vulgaris2 and usu- ally develops in patients who have received oral antibiotics over prolonged periods.3 the occipital and parietal areas, and on the posterior Citrobacter infections are rare and may affect both area of the neck, with occasional development of ery- infants and adults. Authors have reported bac- thema and papules on the face, particularly on the teremias in elderly or immunocompromised patients,4 chin and cheeks. Folliculitis decalvans and rosacea vertical transmission from mother to infant,5 and had been clinically diagnosed. -

Hair and Nails

Dermatology Hair and nails Paul Grinzi The hair and nails are often neglected in our dermatological Background assessments, as the sheer number and breadth of Hair and nails are elements of dermatology that can often conditions affecting the skin can seem overwhelming. This be omitted from the dermatological assessment. However, article focuses on common and important presentations to there are common and distressing hair and nail conditions that require diagnosis and management. general practice, including general and specific conditions affecting both hair and nails. Objective This article considers common and important hair and nail Hair presentations to general practice. General and specific conditions will be discussed. Structure and function Discussion Although hair no longer has any vital physiological function, its social Hair conditions may have significant psychological and psychological role is extremely important. Abnormalities of hair implications. This article considers assessment and often significantly affect self image and the associated psychological management of conditions of too much hair, hair loss or distress should not be ignored or dismissed. hair in the wrong places. It also considers the common nail Hair arises from the hair matrix (part of the epidermis) and is made conditions seen in general practice and provides a guide to up of modified keratin. In humans, hair follicles show intermittent diagnosis and management. activity. Over its lifecycle, each hair grows to a maximum length (this Keywords: nail diseases; hair diseases; hirsutism; phase is called anagen and can last 3–7 years), and is retained for a alopecia; onychomycosis; skin diseases short time without further growth (catagen, this phase lasts from a few days to 2 weeks), and is eventually shed and replaced (telogen, variable period) by a new anagen phase (Figure 1). -

Jaocdjournaljournal Ofof Thethe Americanamerican Osteopathicosteopathic Collegecollege Ofof Dermatologydermatology

Volume 33 JAOCDJournalJournal OfOf TheThe AmericanAmerican OsteopathicOsteopathic CollegeCollege OfOf DermatologyDermatology FocusFocus onon FlushingFlushing TriggersTriggers AA NeuralNeural LinkLink toto UnderstandingUnderstanding RosaceaRosacea Also in this issue: Adult-onset Multisystemic Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis Review of Secukinumab Phase III Testing: A New Hope for Plaque Psoriasis? Concurrent Unilesional Follicular and Syringotropic Mycosis Fungoides last modified on September 11, 2015 10:08 AM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC COLLEGE OF DERMATOLOGY Page 1 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN OSTEOPATHIC COLLEGE OF DERMATOLOGY 2014-2015 AOCD OFFICERS PRESIDENT Rick Lin, DO, FAOCD PRESIDENT-ELECT Alpesh Desai, DO, FAOCD FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT Karthik Krishnamurthy, DO, FAOCD SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT Daniel Ladd, DO, FAOCD THIRD VICE-PRESIDENT John P. Minni, DO, FAOCD Editor-in-Chief SECRETARY-TREASURER Karthik Krishnamurthy, DO Jere J. Mammino, DO, FAOCD TRUSTEES Danica Alexander, DO, FAOCD (2012-2015) Reagan Anderson, DO, FAOCD (2012-2015) Michael Whitworth, DO, FAOCD (2013-2016) Tracy Favreau, DO, FAOCD (2013-2016) Sponsors: David Cleaver, DO, FAOCD (2014-2017) Amy Spizuoco, DO, FAOCD (2014-2017) AuroraDx Immediate Past-President Ranbaxy Suzanne Sirota Rozenberg, DO, FAOCD EEC Representatives Valeant James Bernard, DO, FAOCD Michael Scott, DO, FAOCD Finance Committee Representative Donald Tillman, DO, FAOCD AOBD Representative Stephen Purcell, DO, FAOCD Executive Director Marsha A. Wise, BS AOCD • 2902 N. Baltimore St. • Kirksville, MO 63501 800-449-2623 • FAX: 660-627-2623 • www.aocd.org COPYRIGHT AND PERMISSION: Written permission must be obtained from the Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology for copying or reprinting text of more than half a page, tables or figures. Permissions are normally granted contingent upon similar permission from the author(s), inclusion of acknowledgment of the original source, and a payment of $15 per page, table or figure of reproduced material. -

A Case of Folliculitis Decalvans with Concomitant Acne Keloidalis

FEATURE ARTICLE ANCC 1.5 Contact Hours 0.5 Pharmacology Contact Hour A Case of Folliculitis Decalvans With Concomitant Acne Keloidalis Nuchae, Androgenic Alopecia, and Profound Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation Mitchell Gleed, Kim Carlson ABSTRACT: Folliculitis decalvans is a cicatricial alopecia CASE REPORT of the parietal scalp and vertex characterized by History of Present Illness erythematous, scarred, confluent patches of alopecia with scattered peripheral pustules and scale. It is most A 37-year-old African American man presented to the common among middle-aged men and is frequently outpatient dermatology clinic complaining of pruritic lesions associated with acne keloidalis nuchae. The pathogen- of the scalp and associated hair loss that had been worsening esis of folliculitis decalvans is not completely understood, over the past month. He described his scalp lesions as but it likely involves an inappropriate inflammatory extremely itchy, mildly painful, and dry; they also frequently response to components of Staphylococcus aureus. would bleed when scratched. Folliculitis decalvans is a chronic disease characterized In 2004, the patient began to develop erythematous by periods of remission and exacerbation. Patients with papules and pustules on his scalp after regularly sharing long-standing, undertreated disease can experience a hard hat with a coworker. At that time, he was diagnosed severe hair loss and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. with superficial bacterial folliculitis and was treated with a Treatment is focused on reducing inflammation and topical antibiotic, which temporarily alleviated his symp- bacterial load using oral antibiotic therapy. Early recog- toms. The patient stated, however, that the lesions returned nition and treatment is paramount to alleviate symptoms quickly and persisted since that time, although the severity and limit irreversible hair loss. -

JAOCD July 09.Indd

Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology Volume 14, Number 1 SPONSORS: ',/"!,0!4(/,/'9,!"/2!4/29s-%$)#)3 July 2009 '!,$%2-!s2!."!89 www.aocd.org Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology Journal of the American Osteopathic College of Dermatology 2008-2009 Officers President: Donald K. Tillman, Jr., D.O., FAOCD President Elect: Marc I. Epstein, D.O., FAOCD First Vice President: Leslie Kramer, D.O., FAOCD Second Vice President: Bradley P. Glick, D.O., FAOCD Third Vice President: James B. Towry, D.O., FAOCD Secretary-Treasurer: Jere J. Mammino, D.O., FAOCD Immediate Past President: Jay S. Gottlieb, D.O., FAOCD Trustees: David L. Grice, D.O., FAOCD Mark A. Kuriata, D.O., FAOCD Karen E. Neubauer, D.O., FAOCD Editors Rick Lin, D.O., FAOCD Jay S. Gottlieb, DO Suzanne Rozenberg, D.O., FAOCD Jon Keeling, DO David Geiss, D.O., FAOCD Andrew Racette, DO Executive Director: Rebecca (Becky) Mansfield Editorial Review Board Kevin Belasco, DO Sponsors: Iqbal Bukhari, MD Global Pathology Laboratory Daniel Buscaglia, DO Medicis Igor Chaplik, DO Tejas Desai, DO Galderma Brad Glick, DO Ranbaxy Melinda Greenfield, DO Andrew Hanley, MD David Horowitz, DO JAOCD Rachel Kushner, DO Founding Sponsor Mark Lebwohl, MD !/#$s%)LLINOISs+IRKSVILLE -/ Matt Leavitt, DO s&!8 WWWAOCDORG Cindy Li, DO Rick Lin, DO #/092)'(4!.$0%2-)33)/.WRITTENPERMISSIONMUSTBEOBTAINED FROMTHE*OURNALOFTHE!MERICAN/STEOPATHIC#OLLEGEOF$ERMATOLOGY Jere Mammino, DO FORCOPYINGORREPRINTINGTEXTOFMORETHANHALFPAGE TABLESORlGURES John Minni, DO 0ERMISSIONSARENORMALLYGRANTEDCONTINGENTUPONSIMILARPERMISSION -

Jemds.Com Original Article

Jemds.com Original Article A CLINICAL OBSERVATIONAL STUDY OF OROCUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS IN PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV/AIDS Nayeem Sadath Haneef1 1Professor and HOD, Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprosy, Deccan College of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad. ABSTRACT CONTEXT India has third highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS patients in the world. There were an estimated 2.31 million (1.8-2.9 million) people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) in India in 2007, whereas, slightly declining to 2.1 million in 2013. Early diagnosis of this infection is important not only for effective treatment of the affected patient but also for prevention of further transmission to others. Cutaneous manifestations can be an early pointer to this infection and hence play an important role in the control of HIV/AIDS. They are also useful for clinical staging (WHO staging) of these patients for therapeutic and prognostic purposes, especially in the absence of sophisticated laboratory facilities, as in many parts of India. The profile of cutaneous manifestations in HIV/AIDS patients varies according to their CD4 count. Some of these manifestations are also unique to certain geographic areas. AIMS To study the local pattern of cutaneous and oral manifestations in people living with HIV/AIDS. SETTINGS AND DESIGN A clinical, observational study was conducted among patients consulting Dermatology, Venereology and Leprosy Department of a Tertiary Care, Medical College Hospital in Telangana State, South India. METHODS AND MATERIAL A total of 120 patients of HIV/AIDS, detected by ELISA or other tests, belonging to all age groups and sexes were included. RESULTS Most common cutaneous manifestations observed were pruritic papular rash (20.8%), scabies (12.5%), folliculitis (11.7%), dermatophytosis (10.8%), xerosis (10.8%), seborrhoeic dermatitis (10%), drug rashes (9.2%), candidal vaginitis (5%), molluscum contagiosum (4.2%), and herpes genitalis (3.3%). -

2019 Texas FI PA Results Ready for Formatting 3-29-20

2019 Texas Fully Insured Pharmacy Prior Authorization Requests Summary Prior Prior Total % Prior % Prior Appeal Appeal Total % Appeals % Appeals IRO Denials IRO Denials Total % IRO % IRO Authorization Authorization Prior Authorizations Authorizations Denials Denials Appeals Upheld Overturned Upheld Overturned IRO Upheld Overturned Approvals Denials Authorizations Approved Denied Upheld Overturned 23,211 7,514 30,725 76% 24% 235 293 528 45% 55% 7 1 8 88% 13% #Proprietary 1 of 83 2019 Texas Pharmacy Prior Authorization Report by Drug Name and 6-digit GPI Drug Name 1st 6 Prior Prior Total Prior % Prior % Prior Appeal Appeal Total Appeals % Appeals % Appeals IRO Denials IRO Denials Total IRO % IRO % IRO digits of Authorization Authorization Authorizations Authorizations Authorizations Denials Denials Upheld Overturned Upheld Overturned Upheld Overturned GPI Approval Denial Approved Denied Upheld Overturned 1STMEDX-PATC 908599 2 2 0% 100% ABILIFY 592500 6 4 10 60% 40% ABIRATERONE 214060 6 6 100% 0% ABSORICA 900500 47 26 73 64% 36% 1 1 2 50% 50% ACANYA 900599 1 1 2 50% 50% ACCU-CHEK 941000 3 2 5 60% 40% ACETAMINOPHEN CAFFEINE 659913 3 2 5 60% 40% ACETAMINOPHEN CODEINE 659910 192 16 208 92% 8% ACETAZOLAMIDE 371000 9 5 14 64% 36% 2 2 0% 100% ACETAZOLAMIDE 611000 2 2 100% 0% ACIPHEX 492700 6 4 10 60% 40% ACITRETIN 902505 1 1 100% 0% ACTEMRA 665000 17 9 26 65% 35% 2 2 0% 100% ACTICLATE 665000 1 1 100% 0% ACTONEL 300420 1 1 100% 0% ACTOPLUS 279980 1 1 100% 0% ACZONE 900510 248 11 259 96% 4% ADAPALENE 900500 11 2 13 85% 15% ADAPALENE 900599 13 5