The Quintessentially English Tune an Appraisal of the ʻcut-Timeʼ Hornpipe, Using Examples from the Burnett Ms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Danu Study Guide 11.12.Indd

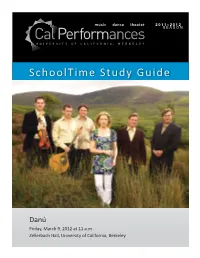

SchoolTime Study Guide Danú Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 9, 2012 at 11 am, your class will a end a performance by Danú the award- winning Irish band. Hailing from historic County Waterford, Danú celebrates Irish music at its fi nest. The group’s energe c concerts feature a lively mix of both ancient music and original repertoire. For over a decade, these virtuosos on fl ute, n whistle, fi ddle, bu on accordion, bouzouki, and vocals have thrilled audiences, winning numerous interna onal awards and recording seven acclaimed albums. Using This Study Guide You can prepare your students for their Cal Performances fi eld trip with the materials in this study guide. Prior to the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student resource sheet on pages 2 & 3 and hand it out to your students several days before the performance. • Discuss the informa on About the Performance & Ar sts and Danú’s Instruments on pages 4-5 with your students. • Read to your students from About the Art Form on page 6-8 and About Ireland on pages 9-11. • Engage your students in two or more of the ac vi es on pages 13-14. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding ques ons, found on pages 2,4,6 & 9. • Immerse students further into the art form by using the glossary and resource sec ons on pages 12 &15. At the performance: Students can ac vely par cipate during the performance by: • LISTENING CAREFULLY to the melodies, harmonies and rhythms • OBSERVING how the musicians and singers work together, some mes playing in solos, duets, trios and as an ensemble • THINKING ABOUT the culture, history, ideas and emo ons expressed through the music • MARVELING at the skill of the musicians • REFLECTING on the sounds and sights experienced at the theater. -

Traditional Fiddle Music of the Scottish Borders

CD Included Traditional Fiddle Music of the Scottish Borders from the playing of Tom Hughes of Jedburgh Sixty tunes from Tom’s repertoire inherited from a rich, regional family tradition fully transcribed with an analysis of Tom’s old traditional style. by Peter Shepheard Traditional Fiddle Music of the Scottish Borders from the playing of Tom Hughes of Jedburgh A Player’s Guide to Regional Style Bowing Techniques Repertoire and Dances Music transcribed from sound and video recordings of Tom Hughes and other Border musicians by Peter Shepheard scotlandsmusic 13 Upper Breakish Isle of Skye IV42 8PY . 13 Breacais Ard An t-Eilean Sgitheanach Alba UK Taigh na Teud www.scotlandsmusic.com • Springthyme Music www.springthyme.co.uk [email protected] www.scotlandsmusic.com Taigh na Teud / Scotland’s Music & Springthyme Music ISBN 978-1-906804-80-0 Library Edition (Perfect Bound) ISBN 978-1-906804-78-7 Performer’s Edition (Spiral Bound) ISBN 978-1-906804-79-4 eBook (Download) First published © 2015 Taigh na Teud Music Publishers 13 Upper Breakish, Isle of Skye IV42 8PY www.scotlandsmusic.com [email protected] Springthyme Records/ Springthyme Music Balmalcolm House, Balmalcolm, Cupar, Fife KY15 7TJ www.springthyme.co.uk The rights of the author have been asserted Copyright © 2015 Peter Shepheard Parts of this work have been previously published by Springthyme Records/ Springthyme Music © 1981 A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library. The writer and publisher acknowledge support from the National Lottery through Creative Scotland towards the writing and publication of this title. All Rights Reserved. -

Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using Folk Dance in Secondary Schools

Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part Contemporary Folk Dance Fusion Using folk dance in secondary schools By Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Scourfield Unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage Explore | Discover | Take Part The Full English The Full English was a unique nationwide project unlocking hidden treasures of England’s cultural heritage by making over 58,000 original source documents from 12 major folk collectors available to the world via a ground-breaking nationwide digital archive and learning project. The project was led by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and in partnership with other cultural partners across England. The Full English digital archive (www.vwml.org) continues to provide access to thousands of records detailing traditional folk songs, music, dances, customs and traditions that were collected from across the country. Some of these are known widely, others have lain dormant in notebooks and files within archives for decades. The Full English learning programme worked across the country in 19 different schools including primary, secondary and special educational needs settings. It also worked with a range of cultural partners across England, organising community, family and adult learning events. Supported by the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Folk Music Fund and The Folklore Society. Produced by the English Folk Dance and Song Society (EFDSS), June 2014 Written by: Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield Edited by: Frances Watt Copyright © English Folk Dance and Song Society, Kerry Fletcher, Katie Howson and Paul Schofield, 2014 Permission is granted to make copies of this material for non-commercial educational purposes. -

Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in the Late Lancashire Witches: a Reel Crux?

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 139–49 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.8 Note Brett D. Hirsch Hornpipes and Disordered Dancing in The Late Lancashire Witches: A Reel Crux? A memorable scene in act 3 of Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome’s The Late Lancashire Witches (first performed and published 1634) plays out the bewitching of a wedding party and the comedy that ensues. As the party- goers ‘beginne to daunce’ to ‘Selengers round’, the musicians instead ‘play another tune’ and ‘then fall into many’ (F4r).1 With both diabolical interven- tion (‘the Divell ride o’ your Fiddlestickes’) and alcoholic excess (‘drunken rogues’) suspected as causes of the confusion, Doughty instructs the musi- cians to ‘begin againe soberly’ with another tune, ‘The Beginning of the World’, but the result is more chaos, with ‘Every one [playing] a seuerall tune’ at once (F4r). The music then suddenly ceases altogether, despite the fiddlers claiming that they play ‘as loud as [they] can possibly’, before smashing their instruments in frustration (F4v). With neither fiddles nor any doubt left that witchcraft is to blame, Whet- stone calls in a piper as a substitute since it is well known that ‘no Witchcraft can take hold of a Lancashire Bag-pipe, for itselfe is able to charme the Divell’ (F4v). Instructed to play ‘a lusty Horne-pipe’, the piper plays with ‘all [join- ing] into the daunce’, both ‘young and old’ (G1r). The stage directions call for the bride and bridegroom, Lawrence and Parnell, to ‘reele in the daunce’ (G1r). At the end of the dance, which concludes the scene, the piper vanishes ‘no bodie knowes how’ along with Moll Spencer, one of the dancers who, unbeknownst to the rest of the party, is the witch responsible (G1r). -

2020 Syllabus

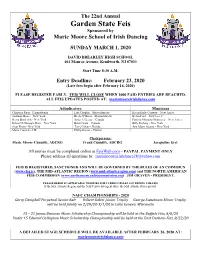

The 22nd Annual Garden State Feis Sponsored by Marie Moore School of Irish Dancing SUNDAY MARCH 1, 2020 DAVID BREARLEY HIGH SCHOOL 401 Monroe Avenue, Kenilworth, NJ 07033 Start Time 8:30 A.M. Entry Deadline: February 23, 2020 (Late fees begin after February 16, 2020) PLEASE REGISTER EARLY. FEIS WILL CLOSE WHEN 1000 PAID ENTRIES ARE REACHED. ALL FEIS UPDATES POSTED AT: mariemooreirishdance.com Adjudicators Musicians Christina Ryan - Pennsylvania Lisa Chaplin – Massachusetts Karen Early-Conway – New Jersey Siobhan Moore - New York Breda O’Brien – Massachusetts Kevin Ford – New Jersey Kerry Broderick - New York Jackie O’Leary – Canada Patricia Moriarty-Morrissey – New Jersey Eileen McDonagh-Morr – New York Brian Grant – Canada Billy Furlong - New York Sean Flynn - New York Terry Gillan – Florida Ann Marie Acosta – New York Marie Connell – UK Philip Owens – Florida Chairpersons: Marie Moore-Cunniffe, ADCRG Frank Cunniffe, ADCRG Jacqueline Erel All entries must be completed online at FeisWeb.com – PAYPAL PAYMENT ONLY Please address all questions to: [email protected] FEIS IS REGISTERED, SANCTIONED AND WILL BE GOVERNED BY THE RULES OF AN COIMISIUN (www.clrg.ie), THE MID-ATLANTIC REGION (www.mid-atlanticregion.com) and THE NORTH AMERICAN FEIS COMMISSION (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) JIM GRAVEN - PRESIDENT. PLEASE REFER TO APPLICABLE WEBSITES FOR CURRENT RULES GOVERNING THE FEIS If the Mid-Atlantic Region and the NAFC have divergent rules, the Mid-Atlantic Rules prevail. NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS - 2020 Gerry Campbell Perpetual -

Suggested Repertoire

THE LEINSTER SCHOOL OF RATE YOUR ABILITY REPERTOIRE LIST MUSIC & DRAMA Level 1 Repertoire List Bog Down in the Valley Garryowen Polka Level 2 Repertoire List Maggie in the Woods Planxty Fanny Power Level 3 Repertoire List Jigs Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle The Kesh Jig (Tom Morley) The Hag’s Purse Blarney Pilgrim The Merry Blacksmith The Swallowtail Jig Tobin’s Favourite Double Jigs: (two, and three part jigs) The Hag at the Churn I Buried My Wife and Danced on her Grave The Carraroe Jig The Bride’s Favourite Saddle the Pony Rambling Pitchfork The Geese in the Bog (Key of C or D) The Lilting Banshee The Mist Covered Meadow (Junior Crehan Tune) Strike the Gay Harp Trip it Upstairs Slip Jigs: (two, and three part jigs) The Butterfly Éilish Kelly’s Delight Drops of Brandy The Foxhunter’s Deirdre’s Fancy Fig for a Kiss The Snowy Path (Altan) Drops of Spring Water Hornpipes Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle Napoleon Crossing the Alps (Tom Morley) The Harvest Home Murphys Hornpipes: (two part tunes) The Boys of Bluehill The Homeruler The Pride of Petravore Cornin’s The Galway Hornpipe Off to Chicago The Harvest Home Slides Slides (Two and three Parts) The Brosna Slides 1&2 Dan O’Keefes The Kerry Slide Merrily Kiss the Quaker Reels Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle The Raven’s Wing (Tom Morley) The Maid Behind the Bar Miss Monaghan The Silver Spear The Abbey Reel Castle Kelly Reels: (two part reels) The Crooked Rd to Dublin The Earl’s Chair The Silver Spear The Merry Blacksmith The Morning Star Martin Wynne’s No 1 Paddy Fahy’s No 1 Fr. -

Ceilidhsoc Tunebook, Web Edition

The Greene Tunebook Tunes from The Red House, WWW Edition Hello Folks This tunebook attempts to bring together the music that has been played at the Red House session over the past few years, as well as some new tunes that people would like to introduce and a little local talent. There will always be several different ways to play folk tunes - what I have tried to do is write down the versions that will be most familiar to the musicians who play at the session. Where chords are given that are, as far as possible, the bog standard ones (not the weard and wonderful ones, as Steve would say!) to help rhythm players. To the best of my knowledge the runes are all tradidional unless an author is named. I'd like to thank (in no particular order): Micky, Simon, Ruth, Susannah, Jess, Richard, Rob, Alison, Phil, Paul and all current ceilisocks for their runes and suggestions. And Anna, for putting up with me typing in tunes in the middle of the night. Hope it's useful! Richard John Greene Contents / Crib Sheet 500, La 1 Trad 72nd's Farewell to Aberdeen 1 March, Trad After the Battle of Aughrim 1 Trad Angeline the Baker 1 Trad Around the World for Sport 2 Trad Atholl Highlanders 2 Kevin Briggs Auld Grey Cat 2 Trad Ballydesmond Polkas, The 3 Trad Banish Misfortune 3 Trad Bear Dance 3 Trad Behind the haystack 3 Trad Blackthorn Stick 4 Trad Blarney Pilgrim, The 4 Trad Bonny Kate 4 Trad Bourree de Ceilidh Monster 5 Phil Waters Bourree Tournante 5 Trad Boys of Bluehill 5 Trad Breton Dance Tune 6 Trad Brighton Camp 6 Trad Bunch Of Keys, The 6 Trad i Butterfly, -

Dance, Space and Subjectivity

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CHICHESTER an accredited college of the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON DANCE, SPACE AND SUBJECTIVITY Valerie A. Briginshaw This thesis is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by publication. DANCE DEPARTMENT, SCHOOL OF THE ARTS October 2001 This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a higher degree of the University of Southampton. WS 2205643 2 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 ..::r'.). NE '2...10 0 2. UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CmCHESTER an accredited college of the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DANCE Doctor of Philosophy DANCE, SPACE AND SUBJECTIVITY by Valerie A. Briginshaw This thesis has been completed as a requirement for a higher degree of the University of Southampton Thisthesis, by examining relationships between dancing bodies and space, argues that postmodern dance can challenge traditional representations of subjectivity and suggest alternatives. Through close readings of postmodern dances, informed by current critical theory, constructions of subjectivity are explored. The limits and extent of subjectivity are exposed when and where bodies meet space. Through a precise focus on this body/space interface, I reveal various ways in which dance can challenge, trouble and question fixed perceptions of subjectivity. The representation in dance of the constituents of difference that partly make up subjectivity, (such as gender, 'race', sexuality and ability), is a main focus in the exploration of body/space relationships presented in the thesis. Based on the premise that dance, space and subjectivity are constructions that can mutually inform and construct each other, this thesis offers frameworks for exploring space and subjectivity in dance. These explorations draw on a selective reading of pertinent poststructuralist theories which are all concerned with critiquing the premises of Western philosophy, which revolve around the concept of an ideal, rational, unified subject, which, in turn, relies on dualistic thinking that enforces a way of seeing things in terms of binary oppositions. -

Paradigmatic of Folk Music Tradition?

‘Fiddlers’ Tunebooks’ - Vernacular Instrumental Manuscript Sources 1860-c1880: Paradigmatic of Folk Music Tradition? By: Rebecca Emma Dellow A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music June 2018 2 Abstract Fiddlers’ Tunebooks are handwritten manuscript books preserving remnants of a largely amateur, monophonic, instrumental practice. These sources are vastly under- explored academically, reflecting a wider omission in scholarship of instrumental music participated in by ‘ordinary’ people in nineteenth-century England. The tunebooks generate interest amongst current folk music enthusiasts, and as such can be subject to a “burden of expectation”,1 in the belief that they represent folk music tradition. Yet both the concepts of tradition and folk music are problematic. By considering folk music from both an inherited perspective and a modern scholarly interpretation, this thesis examines the place of the tunebooks in notions of English folk music tradition. A historical musicological methodology is applied to three post-1850 case-study manuscripts drawing specifically on source studies, archival research and quantitative analysis. The study explores compilers’ demographic traits and examines content, establishing the existence of a heterogeneous repertoire copied from contemporary textual sources directly into the tunebooks. This raises important questions regarding the role played by publishers and the concept of continuous survival in notions of tradition. A significant finding reveals the interaction between aural and literate practices, having important implications in the inward and outward transmission and in wider historical application. The function of both the manuscripts and the musical practice is explored and the compilers’ acquisition of skill and sources is examined. -

Border Pipes

IN THIS ISSUE Letters(3): Mouth Blown Pipes(4): North Hero 2003(7): Summer School 2003(8): Hamish Moore Concert(12): Interview - Robbie Greensitt Ann Sessoms(15): Dance to Your Daddy tune (23): Washingtons march(24): "Bagpipes and Border Pipers"(26): Jackie Latin(32): Harmonic Proportion(34): Collogue 2003(38): Reviews(52): Letters appropriate key were again made. From Peter Aitchison Sets pitched in D with Highland Dunbar, Scotland fingering had actually been made in the mid-19 t century by the Glasgow Looking back into the Common Stock maker William Gunn. Sets fitted with issue of Dec 2002 [Vol 17 No.2], practice chanters exist but they suffer Nigel Bridges writes about the from the poor intonation and tone of strathspey "The Gruagach" by P/M the miniature pipes. D.R.MacLeennan on page three. On In my opinion the revival of any page fourteen Iain Maclnnes mentions instrument or tradition depends upon D.R.MacLellan. Maybe it should be several factors. There must be an D.R.MacLennan? P.S. I knew him. interest or demand for the particular instrument, there must be music appropriate to the instrument, and From Robbie Greensitt there must be instruments available. Monkseaton Northumberland This implies that there must be EDITORIAL hit the streets and, judging by the [abridged - Ed] makers, players and music publishers, The cover picture of a musette was orders and comments, has been well I was surprised by Colin Ross and as well as other enthusiasts like purchasd by Ian Mackay in Bombay! The received. assertion in the June issue of Common historians, working together to promote the revival. -

2.5 Graded Requirements: Irish Traditional Music

2.5 Graded requirements: Irish Traditional Music See page 43 for the graded requirements for bodhrán examinations. Step - Irish Traditional Music The candidate will be expected to perform four tunes. The tunes should be simple in type (for example, easy marches, airs, polkas, etc). No ornamentation or embellishment will be expected but credit will be given for accuracy, fluency, phrasing and style. 25 marks per piece. See page 24 for suggested repertoire for this grade. Grade 1 - Irish Traditional Music See page 24 for suggested repertoire for this grade. Component 1: Performance 60 marks The candidate will be expected to perform three tunes of different types. Ornamentation is not required but the performance should be fluent, well phrased and in style. Component 2: Repertoire 20 marks Three tunes of different types should be prepared and one will be heard at the examiner’s discretion. Ornamentation is not required but the performance should be fluent, well phrased and in style. Component 3: Supplementary Tests 20 marks x To beat time (clap or foot tap) in a polka, double jig or reel performed by the examiner. x To identify tune types (air, polka or double jig) performed by the examiner. x To identify instruments (tin whistle, flute, fiddle, accordion) in audio extracts played by the examiner. x To describe the candidate’s own instrument in detail and name a prominent player of the instrument. Grade 2 - Irish Traditional Music See page 24 for suggested repertoire for this grade. Component 1: Performance 60 marks The candidate will be expected to perform three tunes of different types, at least one of which must be a hornpipe, jig or reel.