Ms. Marvel: Genre, Medium, and an Intersectional Superhero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

The Transition of Black One-Dimensional Characters from Film to Video Games

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 2016 The ewN Black Face: The rT ansition of Black One- Dimensional Characters from Film to Video Games Kyle A. Harris Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Harris, Kyle A. "The eN w Black Face: The rT ansition of Black One-Dimensional Characters from Film to Video Games." (Spring 2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEW BLACK FACE: THE TRANSITION OF BLACK ONE-DIMENSIONAL CHARACTERS FROM FILM TO VIDEO GAMES By Kyle A. Harris B.A., Southern Illinois University, 2013 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Department of Mass Communications and Media Arts in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2016 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL THE NEW BLACK FACE: THE TRANSITION OF BLACK ONE-DIMENSIONAL CHARACTERS FROM FILM TO VIDEO GAMES By Kyle A. Harris A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the field of Professional Media, Media Management Approved by: Dr. William Novotny Lawrence Department of Mass Communications and Media Arts In the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale -

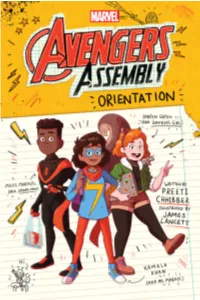

Avengersassembly Orientation

By Preeti Chhibber Illustrated by James Lancett Scholastic Inc. © 2020 MARVEL All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. scholastic and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 978-1-338-58725-8 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. 23 First printing 2020 Book design by Katie Fitch HERO CARD #148 powers NAME: KAMALA KHAN, AKA MS. MARVEL POWERS: Embiggening! Disembiggening! Stretching! Shape-shifting! ms. marvel HERO CARD #477 powers NAME: MILES MORALES, AKA ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN POWERS: Wall-crawling, expo- nential strength, electric shocks, being invisible, but not being creepy like a spider, that is for sure. spider-man HERO CARD #091 powers NAME: DOREEN GREEN, AKA SQUIRREL GIRL POWERS: Powers of a squirrel and (more importantly) powers of a girl. -

An Analysis of Ms. Marvel's Kamala Khan

The “Worlding” of the Muslim Superheroine: An Analysis of Ms. Marvel’s Kamala Khan SAFIYYA HOSEIN Muslim women have been a source of speculation for Western audiences from time immemorial. At first eroticized in harem paintings, they later became the quintessential image of subservience: a weakling to be pitied and rescued from savage Brown men. Current depictions of Muslim women have ranged from the oppressed archetype in mainstream media with films such as The Stoning of Soraya M (2008) to comedic veiled characters in shows like Little Mosque on the Prairie (2012). One segment of media that has recently offered promising attempts for destabilizing their image has been comics and graphic novels which have published graphic memoirs that speak to the complexity of Muslim identity as well as superhero comics that offer a range of Muslim characters from a variety of cultures with different levels of religiosity. This paper explores the emergence of the Muslim superheroine in comic books by analyzing the most developed Muslimah (Muslim female) superhero: the rebooted Ms. Marvel superhero, Kamala Khan, from the Marvel Comics Ms. Marvel series. The analysis illustrates how the reconfiguration of the Muslim female archetype through the “worlding” of the Muslim superhero continues to perpetuate an imperialist agenda for the Third World. This paper uses Gayatri Spivak’s “worlding” which examines the “othered” natives and the global South as defined through Eurocentric terms by imperialists and colonizers. By interrogating Kamala’s representation, I argue that her portrayal as a “moderate” Muslim superheroine with Western progressive values can have the effect of reinforcing Safiyya Hosein is a Ph.D. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Costume Culture: Visual Rhetoric, Iconography, and Tokenism In

COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS A Dissertation by MICHAEL G. BAKER Submitted to: Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez Committee: Tabetha Adkins Donna Dunbar-Odom Mike Odom Head of Department: M. Hunter Hayes Dean of the College: Salvatore Attardo Interim Dean of Graduate Studies: Mary Beth Sampson iii Copyright © 2017 Michael G. Baker iv ABSTRACT COSTUME CULTURE: VISUAL RHETORIC, ICONOGRAPHY, AND TOKENISM IN COMIC BOOKS Michael G. Baker, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2017 Advisor: Christopher Gonzalez, PhD Superhero comic books provide a unique perspective on marginalized characters not only as objects of literary study, but also as opportunities for rhetorical analysis. There are representations of race, gender, sexuality, and identity in the costuming of superheroes that impact how the audience perceives the characters. Because of the association between iconography and identity, the superhero costume becomes linked with the superhero persona (for example the Superman “S” logo is a stand-in for the character). However, when iconography is affected by issues of tokenism, the rhetorical message associated with the symbol becomes more difficult to decode. Since comic books are sales-oriented and have a plethora of tie-in merchandise, the iconography in these symbols has commodified implications for those who choose to interact with them. When consumers costume themselves with the visual rhetoric associated with comic superheroes, the wearers engage in a rhetorical discussion where they perpetuate whatever message the audience places on that image. -

Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 Free Ebook

FREEMS. MARVEL: VOL. 2 EBOOK Adrian Alphona,Takeshi Miyazawa,G. Willow Wilson | 240 pages | 19 Apr 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785198369 | English | New York, United States Ms Marvel (Vol 2) #8 VF 1st Print Marvel Comics | eBay Marvel is the name of several fictional superheroes appearing in comic books published by Marvel Comics. The character was originally conceived as a female counterpart to Captain Marvel. Like Captain Marvel, most of the bearers of the Ms. Marvel title gain their powers through Kree technology or genetics. Marvel has published four ongoing comic series titled Ms. Marvelwith the first two starring Carol Danvers and the third and fourth starring Kamala Khan. Carol Danvers, the first character to use the moniker Ms. Marvel 1 January with super powers as result of the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 which caused her DNA Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 merge with Captain Marvel's. As Ms. Danvers goes on to use the codenames Binary [1] and Warbird. Sharon Ventura, the second character to use the pseudonym Ms. Ventura later joins the Fantastic Four herself in Fantastic Four October and, after being hit by cosmic rays in Fantastic Four JanuaryVentura's body mutates into a similar appearance to that of The Thing and receives the nickname She-Thing. Sofen tricks Bloch into giving her the meteorite that empowers him, and she adopts both the Ms. Marvel: Vol. 2 and abilities of Moonstone. Marvel, Carol Danvers, receiving a costume similar to Danvers' original Danvers wore the Warbird costume at the time. Marvel series beginning in issue 38 June until Danvers takes the title back in issue 47 January Kamala Khan, created by Sana AmanatG. -

Batman in the 50S Free

FREE BATMAN IN THE 50S PDF Joe Samachson,Various,Edmond Hamilton,Bill Finger,Bob Kane,Dick Sprang,Stan Kaye,Sheldon Moldoff | 191 pages | 01 May 2002 | DC Comics | 9781563898105 | English | United States Batman in the Fifties (Collected) | DC Database | Fandom An instantly recognizable theme song, outrageous death traps, ingenious gadgets, an army of dastardly villains and femme fatales, and a pop-culture phenomenon unmatched for generations. James Bondright? When it first premiered inBatman was the most faithful adaptation of a bona fide comic book superhero ever seen on the screen. It was a nearly perfect blend of the Saturday matinee movie serials where most comic book characters had their first Hollywood break and the comics of its time. But the TV series, particularly during its genesis, was both a product of its own time, and that of an earlier era. Both Flash Gordon and Dick Tracy had made the leap to the big screen before Superman had even hit newsstands, and both saw their serial adventures get two sequels. While Flash Gordonparticularly the first one, was a faithful within the limitations of its budget translation of the Alex Raymond comic strips, Dick Tracy was less so. Years before Richard Donner and Christopher Reevethis one made audiences believe a man could fly, and featured a perfectly cast Tom Tyler in the title role, but was still rather beholden to serial storytelling conventions and the aforementioned budgetary limitations. Ad — content continues below. Batman and Robin are portrayed much as they are in the comics, despite some unfortunately cheap costumes, and less than physically convincing actors in the title roles. -

A Lesbian Masquerade

Accessory to Murder: A Lesbian Masquerade Rob K. Baum ABSTRACT Mabel Maney parodies Fifties-era "girl detective" Nancy Drew with lesbian Nancy Clue, mocking the original series' insistence upon heteronormativity while maintaining Keene's luxuriously white, upper class sanctity. This article explores Maney's comic structure from Freudian "dress-up" and professional disguise to lesbian masquerade, demonstrating their ideological difference from gay camp - one queer commentary has repeatedly confused. Maney's conflation of the disparate motives of lesbian masquerade and gay camp lead to her abandonment of lesbian feminist readers. RESUME Mabel Maney fait la parodie de la "fille d£tecfive"des annees 50 Nancy Drew avec la lesbienne Nancy Clue en se moquant de I'insistence que la serie originale portait sur I'heteronormativite tout en gardant la sanctite de la classe superieure luxurieusement blanche. Cet article explore la structure comique de Maney du "deguisement" freudien et du ddguisement professionnel a la masquarade lesbienne, en expliquant leur difference ideologique avec celle du camp gay - ce qu'un commentaire homosexuel a embrouill6 a maintes reprises. L'assemblage que Maney a fait de la disparite des motifs de la masquarade lesbienne et du camp gay l'a porte a delaisser les lectrices feministes lesbiennes. From what we have seen...in this double reading of alienated girlhood are resurrected and reinforced by lesbian/queer revolutionary activity in America, ... Maney's "world o' girls" (the series' fictional the real fear we face, as scholars and activists, is publishing house), positioning women as either not that queers in America will have sex, but that lesbians or lawbreakers - thus subverting the ...queers in America will have politics. -

Captain Marvel Crossword

Name: Date: CAPTAIN MARVEL CROSSWORD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 ACROSS DOWN 1. The Prime, the Deviants and the Eternals are 2. A close friend that shared a number of adventures three kind of... together. 7. Real Name of Captain Marvel 3. She joined this agency upon graduating from high 9. Captain Marvel leaved her troubles with X-Men on school to pursue her dreams of flying. Earth behind to join space pirates called... 4. Ms. Marvel is also known as... 10. Humanoid alien race descendant of bird-like 5. Enemy that vowed to destroy Ms. Marvel. creatures Shi'ar and enemy of Ms. Marvel. 6. Because of Carol's stellar performance, superb 11. Who performed experiments on Carol’s genetic combat skills and natural intellect, she was structure that unleashed the full potential of recruited by... cosmic power? 8. Ms. Marvel joined and helped them many times. 12. Carol’s genetic structure was changed by an explosion to a perfect hybrid of human and ____________ genes. DEATHBIRD MYSTIQUE KREE AIR FORCE C.I.A. SKRULLS LOGAN STARJAMMERS CAROL DANVERS BINARY BROOD AVENGERS Free Printable Crossword www.AllFreePrintable.com Name: Date: CAPTAIN MARVEL CROSSWORD 1 2 S K R U L L S 3 O A 4 B G I 5 6 7 8 M C I C A R O L D A N V E R S Y I N V N F 9 S T A R J A M M E R S O T R N R 10 D E A T H B I R D Y G C Q E E 11 U B R O O D 12 K R E E S ACROSS DOWN 1. -

Body Bags One Shot (1 Shot) Rock'n

H MAVDS IRON MAN ARMOR DIGEST collects VARIOUS, $9 H MAVDS FF SPACED CREW DIGEST collects #37-40, $9 H MMW INV. IRON MAN V. 5 HC H YOUNG X-MEN V. 1 TPB collects #2-13, $55 collects #1-5, $15 H MMW GA ALL WINNERS V. 3 HC H AVENGERS INT V. 2 K I A TPB Body Bags One Shot (1 shot) collects #9-14, $60 collects #7-13 & ANN 1, $20 JASON PEARSON The wait is over! The highly anticipated and much debated return of H MMW DAREDEVIL V. 5 HC H ULTIMATE HUMAN TPB JASON PEARSON’s signature creation is here! Mack takes a job that should be easy collects #42-53 & NBE #4, $55 collects #1-4, $16 money, but leave it to his daughter Panda to screw it all to hell. Trapped on top of a sky- H MMW GA CAP AMERICA V. 3 HC H scraper, surrounded by dozens of well-armed men aiming for the kill…and our ‘heroes’ down DD BY MILLER JANSEN V. 1 TPB to one last bullet. The most exciting BODY BAGS story ever will definitely end with a bang! collects #9-12, $60 collects #158-172 & MORE, $30 H AST X-MEN V. 2 HC H NEW XMEN MORRION ULT V. 3 TPB Rock’N’Roll (1 shot) collects #13-24 & GS #1, $35 collects #142-154, $35 story FÁBIO MOON & GABRIEL BÁ art & cover FÁBIO MOON, GABRIEL BÁ, BRUNO H MYTHOS HC H XMEN 1ST CLASS BAND O’ BROS TP D’ANGELO & KAKO Romeo and Kelsie just want to go home, but life has other plans.