Baptisms in Mixquiahuala, Hidalgo, 1681-17401

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concluye El 1Er Periodo Ordinario Del 3Er Año De Ejercicio De La LXIV Legislatura

Pachuca, Hgo., a 29 de diciembre de 2020. Concluye el 1er periodo ordinario del 3er año de ejercicio de la LXIV Legislatura Este martes 29 de diciembre, integrantes de la LXIV Legislatura del Congreso del Estado de Hidalgo, previo a clausurar los trabajos del Primer Periodo Ordinario de Sesiones del Tercer Año de Ejercicio, sesionaron para aprobar 82 de 84 propuestas de Leyes de Ingresos municipales para igual número de ayuntamientos que serán vigentes durante el Ejercicio Fiscal 2021. Los 82 ayuntamientos a los que les fueron autorizados, son Acatlán, Acaxochitlán, Actopan, Agua Blanca, Ajacuba, Alfajayucan, Almoloya, Apan, Atitalaquia, Atlapexco, Atotonilco de Tula, Atotonilco el Grande, Calnali, Cardonal, Chapantongo, Chapulhuacán, Chilcuautla, Cuautepec de Hinojosa, El Arenal, Eloxochitlán, Emiliano Zapata, Epazoyucan, Francisco I. Madero y Huautla. Asimismo, Huasca de Ocampo, Huazalingo, Huehuetla, Huejutla, Huichapan, Ixmiquilpan, Jacala, Jaltocan, Juárez Hidalgo, La Misión, Lolotla, Metepec, Metztitlán, Mineral de la Reforma, Mineral del Chico, Mineral del Monte, Mixquiahuala, Molango, Nicolás Flores, Nopala, Omitlán de Juárez, Pachuca de Soto, Pacula, Pisaflores, Progreso de Obregón, San Salvador, San Agustín Metzquititlán, San Agustín Tlaxiaca y San Bartolo Tutotepec. También, San Felipe Orizatlán, Santiago de Anaya, Tasquillo, Tecozautla, Tenango de Doria, Tepeapulco, Tepehuacán de Guerrero, Tepeji del Río, Tepetitlán, Tetepango, Tezontepec de Aldama, Tianguistengo, Tizayuca, Tlahuelilpan, Tlahuiltepa, Tlanalapa, Tlanchinol, Tlaxcoapan, Tolcayuca, Tula de Allende, Tulancingo de Bravo, Villa de Tezontepec, Xochiatipan, Xochicoatlán, Yahualica, Zacualtipán de Ángeles, Zapotlán de Juárez, Zempoala y Zimapán. Se explicó que las iniciativas de Leyes de Ingresos que se dictaminan, son congruentes con lo establecido a la Ley de Hacienda para los Municipios del Estado de Hidalgo, al señalar el ámbito y la vigencia de su aplicación, los conceptos de ingresos que constituyen la hacienda pública de los Municipios, así como las reglas que regirán su operación. -

Programa De Fomento Agropecuario Delegación

DELEGACIÓN ESTATAL HIDALGO SUBDELEGACIÓN AGROPECURIA PROGRAMA DE FOMENTO AGROPECUARIO LISTADO DE BENEFICIARIOS DEL COMPONENTE PIMAF ALTA PRODUCTIVIDAD UNIDAD DE NO. FOLIO ESTATAL DISTRITO CADER MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD BENEFICIO DESCRIPCION CANTIDAD MEDIDA 1 HG1400014436 HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN NOPALA DE VILLAGRAN BATHA Y BARRIOS SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 433.60 2 HG1400003250 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN LA VEGA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.00 3 HG1400014773 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN SAN JUAN METZTITLÁN SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 20.00 4 HG1400014784 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN SAN JUAN METZTITLÁN SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.02 5 HG1400004599 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN MADHO CORRALES SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 3.00 6 HG1400003733 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN YONTHE GRANDE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.00 7 HG1400004942 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN SANTA MARÍA LA PALMA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.00 8 HG1400005711 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN PRIMERA MANZANA DOSDHA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.00 9 HG1400004970 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN TERCERA MANZANA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 7.00 10 HG1400004208 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN EL BERMEJO SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 5.00 11 HG1400004640 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN XAMAGE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.00 12 HG1400005043 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN YONTHE GRANDE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 2.00 13 HG1400003742 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN XAMAGE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 2.00 14 HG1400014757 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN ATZOLCINTLA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.08 15 HG1400005744 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN MADHO CORRALES SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 3.00 16 HG1400005254 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN NAXTHEY SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.00 17 HG1400014867 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN SAN JUAN METZTITLÁN SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 9.50 18 HG1400005061 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN EL DOYDHE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. -

Delegación En El Estado De Hidalgo Subdelegación Agropecuaria Jefatura Del Programa De Fomento a La Agricultura Pa

DELEGACIÓN EN EL ESTADO DE HIDALGO SUBDELEGACIÓN AGROPECUARIA JEFATURA DEL PROGRAMA DE FOMENTO A LA AGRICULTURA PADRÓN DE BENEFICIARIOS DEL COMPONENTE REPOBLAMIENTO Y RECRIA PECUARIA-INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO EN LAS UPP MONTO DE NO. ESTADO FOLIO ESTATAL REGION DEL PAIS DISTRITO CADER MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD BENEFICIO DESCRIPCIÓN TIPO DE PERSONA APOYO ($) 1 HIDALGO HG1600005161 centro HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA SAN ANTONIO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP EQUIPO 280,350.00 FÍSICA 2 HIDALGO HG1600005217 centro TULANCINGO SAN BARTOLO TUTOTEPEC METEPEC EL VESUBIO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 241,455.00 FÍSICA 3 HIDALGO HG1600005232 centro TULANCINGO SAN BARTOLO TUTOTEPEC METEPEC LAS TROJAS INFRAESTRUCTURA 238,994.00 FÍSICA 4 HIDALGO HG1600005388 centro TULANCINGO TULANCINGO SINGUILUCAN SANTA ANA CHICHICUAUTLA INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 237,899.20 FÍSICA 5 HIDALGO HG1600005403 centro TULANCINGO TULANCINGO SINGUILUCAN SANTA ANA CHICHICUAUTLA INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 237,899.20 FÍSICA 6 HIDALGO HG1600005422 centro HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA EL SALTO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP EQUIPO 196,000.00 FÍSICA 7 HIDALGO HG1600005434 centro HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA EL SALTO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 18,900.00 FÍSICA 8 HIDALGO HG1600005462 centro MIXQUIAHUALA TULA TULA DE ALLENDE SANTA ANA AHUEHUEPAN INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP EQUIPO 213,689.70 FÍSICA 9 HIDALGO HG1600005481 centro TULANCINGO TULANCINGO SINGUILUCAN EL VENADO -

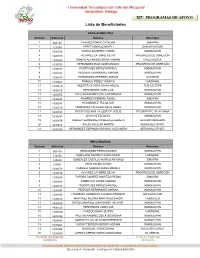

XIV. PROGRAMAS DE APOYO Lista De Beneficiarios

Universidad Tecnológica del Valle del Mezquital Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo. XIV. PROGRAMAS DE APOYO Lista de Beneficiarios BECA ALIMENTICIA Número Matrícula Nombre Municipio 1 083137 CHAVEZ PONCE CATALINA ZIMAPÁN 2 123069 PEREZ IGNACIO NAYELI SAN SALVADOR 3 1330186 VIXTHA QUITERIO YADIRA IXMIQUILPAN 4 1330189 ÁLVAREZ LATORRE SILVIA PROGRESO DE OBREGÓN 5 1330455 RAMOS ALVARADO ERIKA YAZMIN CHILCUAUTLA 6 1330573 HERNÁNDEZ RUIZ JOSÉ MANUEL PROGRESO DE OBREGÓN 7 1330733 RODRÍGUEZ PÉREZ MARISOL IXMIQUILPAN 8 1330741 PEDRAZA HERNÁNDEZ MARINA IXMIQUILPAN 9 1330817 HERNANDEZ HERRERA MIRIAM ACTOPAN 10 1330867 RÓMULO PÉREZ YESSICA CARDONAL 11 1430142 MONTER OLVERA JUAN CARLOS TLAHUILTEPA 12 1430726 HERNANDEZ JOSE LUIS IXMIQUILPAN 13 1430856 FALCON RAMIREZ ZEILA GEORGINA IXMIQUILPAN 14 1530453 RAMÍREZ FERRERA ÁNGEL ZIMAPÁN 15 1530584 HERNÁNDEZ TREJO JAIR IXMIQUILPAN 16 1530719 YERBAFRIA CALLEJAS DALIA HASEL IXMIQUILPAN 17 1630191 BECIEZ ESCAMILLA JOSÉ DE JESÚS TEZONTEPEC DE ALDAMA 18 1630681 ARROYO EZEQUIEL IXMIQUILPAN 19 1630876 JUÁREZ HERNÁNDEZ PAMELA ELIZABETH ÁLVARO OBREGÓN 20 1630917 SALAS AGUILAR MARTÍN NEZAHUALCÓYOTL 21 1630918 HERNÁNDEZ ESPINOSA ROXANA ALEJANDRA NEZAHUALCÓYOTL BECA EQUIDAD Número Matrícula Nombre Municipio 1 053118 HERNANDEZ PEREZ MOISES IXMIQUILPAN 2 113250 MORGADO RAMIREZ GERALDINNE CARDONAL 3 123040 GONZALEZ CASTILLO MARCO ANTONIO ZIMAPÁN 4 123601 PEÑA PALMA CESAR IXMIQUILPAN 5 1330173 CAZUELA GABRIEL DIANA MARELY IXMIQUILPAN 6 1330189 ÁLVAREZ LATORRE SILVIA PROGRESO DE OBREGÓN 7 1330495 TORRES RAMÍREZ MARITZA PIEDAD ZIMAPÁN -

13 Hidalgo Huichapan Huichapan Tecozautla

13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA RIITOEL 1700738098 0.50 481.50 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA RIITOEL 873053 0.50 481.50 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA RIITOEL 1700737296 0.27 260.01 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA GANDHO P.P. 1000494192 1.00 963.00 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA TECOZAUTLA P.P. 1703018192 2.61 2513.43 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TAGUI P.P. 1010059027 4.00 3852.00 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA BANZHA 838834 1.00 963.00 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA BOMANXOTHA 871259 0.89 857.07 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA BOMANXOTHA 1700245640 1.00 963.00 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA BOMANXOTHA 1703013728 0.94 905.22 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA BOMANXOTHA 1000035096 0.53 510.39 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA GANDHO 1000476606 0.75 722.25 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA RIITOEL 1010010418 1.22 1174.86 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA SAN ANTONIO 1701701153 1.42 1367.46 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA SAN ANTONIO 1000477227 0.71 683.73 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA BOMANXOTHA 871181 1.18 1136.34 OI12 RIEGO PROCAMPO 13 HIDALGO HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA PANHE 838814 -

Complementario 4. Aportaciones Por Fondo Y Municipio

Presupuesto de Egresos del Estado de Hidalgo Ejercicio Fiscal 2019 Aportaciones por fondo y municipio Complementario 4 Fondo de Fondo de Aportaciones a la Fortalecimiento Municipio Monto Presupuestado Infraestructura Municipal Acatlán 28,021,607 15,136,756 12,884,851 Acaxochitlán 77,633,477 50,831,469 26,802,008 Actopan 53,199,868 18,649,438 34,550,430 Agua Blanca de Iturbide 17,318,162 11,736,604 5,581,558 Ajacuba 17,314,546 6,097,550 11,216,996 Alfajayucan 36,807,704 24,358,798 12,448,906 Almoloya 16,824,856 9,226,443 7,598,413 Apan 49,993,644 22,700,586 27,293,058 Atitalaquia 23,229,041 5,054,691 18,174,350 Atlapexco 48,345,242 36,159,617 12,185,625 Atotonilco de Tula 30,316,443 6,704,421 23,612,022 Atotonilco el Grande 36,029,572 19,232,855 16,796,717 Calnali 39,737,384 29,228,798 10,508,586 Cardonal 30,057,088 18,823,560 11,233,528 Cuautepec de Hinojosa 77,334,075 41,637,455 35,696,620 Chapantongo 24,926,386 16,483,637 8,442,749 Chapulhuacán 54,528,100 39,857,224 14,670,876 Chilcuautla 28,872,727 17,748,185 11,124,542 El Arenal 20,664,580 9,149,403 11,515,177 Eloxochitlán 7,251,891 5,618,936 1,632,955 Emiliano Zapata 12,838,412 3,761,340 9,077,072 Epazoyucan 12,785,838 3,789,587 8,996,251 Francisco I. -

Porcentaje De La Población Según El Tipo De Carencia Social, Por Municipio Medición De La Pobreza, Hidalgo, 2010

Medición de la pobreza, Hidalgo, 2010 Porcentaje de la población según el tipo de carencia social, por municipio Clave de Entidad federativa Clave de Municipio Población Carencia por entidad municipio calidad y espacios de la vivienda 13 Hidalgo 13001 Acatlán 18,816 9.2 13 Hidalgo 13002 Acaxochitlán 32,389 29.7 13 Hidalgo 13003 Actopan 56,603 10.0 13 Hidalgo 13004 Agua Blanca de Iturbide 7,927 15.1 13 Hidalgo 13005 Ajacuba 15,097 6.1 13 Hidalgo 13006 Alfajayucan 16,397 10.6 13 Hidalgo 13007 Almoloya 10,990 14.6 13 Hidalgo 13008 Apan 38,635 11.7 13 Hidalgo 13009 El Arenal 19,479 16.4 13 Hidalgo 13010 Atitalaquia 31,477 8.4 13 Hidalgo 13011 Atlapexco 16,789 30.8 13 Hidalgo 13012 Atotonilco el Grande 31,226 7.8 13 Hidalgo 13013 Atotonilco de Tula 34, 918 414.1 13 Hidalgo 13014 Calnali 14,922 22.5 13 Hidalgo 13015 Cardonal 17,082 12.3 13 Hidalgo 13016 Cuautepec de Hinojosa 51,572 17.9 13 Hidalgo 13017 Chapantongo 11,691 9.2 13 Hidalgo 13018 Chapulhuacán 20,946 20.8 13 Hidalgo 13019 Chilcuautla 15,154 10.1 13 Hidalgo 13020 Eloxochitlán 2,403 15.5 13 Hidalgo 13021 Emiliano Zapata 14,346 7.5 13 Hidalgo 13022 Epazoyucan 14,924 8.7 13 Hidalgo 13023 Francisco I. Madero 32,377 7.1 13 Hidalgo 13024 Huasca de Ocampo 15,716 9.7 13 Hidalgo 13025 Huautla 20,820 40.2 13 Hidalgo 13026 Huazalingo 10,390 42.5 13 Hidalgo 13027 Huehuetla 20,084 26.9 13 Hidalgo 13028 Huejutla de Reyes 119,281 34.0 13 Hidalgo 13029 Huichapan 47,013 8.8 13 Hidalgo 13030 Ixmiquilpan 86,555 11.7 Medición de la pobreza, Hidalgo, 2010 Porcentaje de la población según el tipo de carencia -

Formato Ejercicio Y Destino

§OBIERNO DEI ESfADO OE H¡DAIGO fOiMATO OELUERCICIO Y OEÍII{O OE GASTO fEOERAUZAOOY REINTEGROS at 310E otctEMeRE oE 2019 PRO6¡AMA5 utRCrCtO F|5(AL 20¡9 EltRcrcto PñOGRAMAO TOÑOO OESTINO DE TOS RECURSOS ñEINf¡GRO OTVENGAOO ' PAGADO GA9IO DE INVERSION: COMISIóN ESTAIAL OET AGUA Y ALCANfARILLAOO 9867,923.00 s867,923.00 s0 00 APOYOA TNsTTTUCTONES ESTATALCS OE CUTfURA (A|EC) CONSE'O ESIATAT PAfiA LA CULTURAY LA5 ARTIS OE HIOATGO 55,000,000.00 s5,000,000.00 50 00 CONSIRUCCIÓN Y EQUIPAMI€NTO DEL HOSPITALGENERAL MEIZTITI,AN SERVICIOS OE SALUO OE HIDAL6O s52,916,011.63 s52.916.011.63 s0.00 lcEHGu) CONSTRUCCIÓN Y EQUIPAMIENTO DEL HOSPITAL 6 EN ERAL ZIMAPAN SERVICIOS DT SALUD OE HIDALGO s30,042,965.93 s30,042,965.93 50.00 (CEHGZI €ULIURA DELAGUA SECREIARfADECoNTRALORIA(oIRECCIÓNGENCRALoEÓRGANOSDECONTROLYvIGILANCIA) s600.00 s600 00 5000 FONDO OE ACCESIS|LIOAD OE ffnSONASCON DTSCAPACTOAO (fOApOl SISTIMA ESTAIAT PARA ET OESARROLLO IN¡EGRAL DE LA fAMITIA HIOALGO s8,776,53E.31 s8.776.538.3r s0 00 toNDo oE aPoRTACTONES MÚ Lfrpt-ES ASTSTENCTA SOCrA! lfAMASl SISfEMA ESTATAT PARA IT OESARROLIO INTCGRAL DT LA fAMILIA HIDALGO s325,293,576.50 §325,293,576 50 50 0o FONDO DE APORTACIONES MÚLTIPTTS OE INTRAESTRUCTURA INSTITUfO HIOALGUENSE DE TA INTRAESTRUCfURA F¡SICA EDUCAfIVA s189,372,494 84 s1a9 312,494.A4 s0 00 EOUCATIVA 8A5ICA IfAMEBI FONOO DE APORTACIONTS MÚLfIPLTS OI INFRATSIRUCIURA INSIIIUfO HIOATGUENSE DE TA INfRAESTRUCTURA FÍSICA EDUCATIVAY $r3,830,233.75 s13,830,233.75 90.00 EDUCATIVA MEOIA SUPTRIOR ITAMMDI UNIVERSIDAD AUfÓNOMA DEL ESTADO OT HIDALGO rONDO -

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Hidalgo Atotonilco De

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula SAN JOSÉ ACOCULCO 991804 195809 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula EL PEDREGAL 991407 195609 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula SAN ANTONIO 991713 195714 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula PRADERAS DEL POTRERO 991349 195305 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula BATHA 991535 195851 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula LA SIERRITA (LA PRESA DEL TEJOCOTE) 991600 195814 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula EL PORTAL 991754 195659 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula SANTA CRUZ DEL TEZONTLE 991402 195642 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula EL VENADO 991759 195655 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula PASEOS DE LA PRADERA 991417 195328 Hidalgo Chapantongo SANTA MARÍA AMEALCO 993257 201414 Hidalgo Chapantongo EL CAPULÍN 993003 201049 Hidalgo Chapantongo JUCHITLÁN 992832 201146 Hidalgo Chapantongo SAN JOSÉ EL MARQUÉS (ESCANDÓN) 993347 201231 Hidalgo Chapantongo SAN ISIDRO 992906 201047 Hidalgo Chapantongo EL CAMARÓN 993042 201141 Hidalgo Chapantongo EL COLORADO (CERRO COLORADO) 992855 201033 Hidalgo Chapantongo RANCHO NUEVO 992936 201204 Hidalgo Chapantongo COLONIA FÉLIX OLVERA 993526 201421 Hidalgo Chapantongo EX-HACIENDA EL MARQUÉS 993218 201256 Hidalgo Chapantongo LA NORIA (EL PLAN) 993405 201429 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán NOPALA 993843 201503 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán BATHA Y BARRIOS 994322 201437 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL BORBOLLÓN 994413 201314 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL CAPULÍN DE ARAGÓN 993653 201202 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL FRESNO (CASAS VIEJAS) 994720 201417 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL CEDAZO 994057 201423 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán -

SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO MEXICANO Carta Inventario Minero Huichapan

SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO MEXICANO Carta Inventario Minero Huichapan F14-C78, Escala 1:50,000 0 SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO MEXICANO ÍNDICE Pag. I. GENERALIDADES 1 I.1. Introducción 1 I.2. Antecedentes 1 I.3. Objetivo 2 II. MEDIO FÍSICO Y GEOGRÁFICO 3 II.1. Localización y Extensión 3 II.2. Breve Bosquejo Histórico 3 II.3. Vías de Comunicación y Acceso 4 II.4. Fisiografía 7 II.5. Hidrografía 8 III. MARCO GEOLÓGICO REGIONAL 10 III.1. Geología Regional 10 III.2. Geología Local 14 IV. YACIMIENTOS MINERALES 18 IV.1. Localidades de Rocas Dimensionables 18 IV.2. Localidades de Agregado Pétreos 75 IV.3. Localidades de Minerales No Metálicos 107 IV.4. Localidades de Minerales Metálicos 119 V. CONCLUSIONES Y RECOMENDACIONES 134 BIBLIOGRAFÍA 141 Carta Inventario Minero Huichapan F14-C78, Escala 1:50,000 1 SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO MEXICANO FIGURAS Pag. Figura 1. Plano de localización de la carta Huichapan F14-C78 3 Figura 2. Plano de vías de acceso y comunicación de la carta Huichapan F14-C78 (INEGI, 2005) 6 Figura 3. Plano de Provincias Fisiográficas de la República Mexicana y su relación con el área de estudio de la carta Huichapan F14-C78 (José Lugo-Hubp, 1990) 7 Figura 4. Regiones Hidrológicas del Estado de Hidalgo y su relación con la carta Huichapan F14-C78 9 Figura 5. Terrenos Tectonoestratigráficos y la ubicación de la carta Huichapan F14-C78 (Campa- Uranga, M. F. and Coney, P. J., 1983) 11 Figura 6. Provincias Geológicas (Ortega-Gutiérrez, F., 1992) y su relación con el área de estudio de la carta Huichapan F14-C78 13 Figura 7. -

Colegio De Bachilleres Del Estado De Hidalgo Cumplimiento Programático Presupuestal Federal Enero-Junio 2014

COLEGIO DE BACHILLERES DEL ESTADO DE HIDALGO CUMPLIMIENTO PROGRAMÁTICO PRESUPUESTAL FEDERAL ENERO-JUNIO 2014 PRESUPUESTO METAS PROGRAMADO/EJERCIDO RADICADO/EJERCIDO (PESOS) PROGRAMADO AL RADICADO AL NO. NOMBRE DEL PROYECTO UNIDAD DE MEDIDA VARIACIÓN VARIACIÓN VARIACIÓN PERÍODO PERÍODO ORIGINAL AMPLIACIÓN REDUCCIÓN MODIFICADA AL PERÍODO ALCANZADA ORIGINAL AMPLIACIÓN REDUCCCIÓN MODIFICADO EJERCIDO (ENE-JUN) (ENE-JUN) CANTIDAD % PESOS % PESOS % 1 SEGUIMIENTO DE BECAS ALUMNO BECADO 11,500 11,500 10,000 10,000 0.0 0% 12,300 12,300 8,800 8,800 6,949 1,851 21.03% 1,851 21.03% VINCULACION 2 VINCULACIÓN 5 5 3 3 0.0 0% 2,694 2,694 1,244 1,244 785 459 36.90% 459 36.90% CONCRETADA 3 EXTENSIÓN BACHILLER ALUMNO APOYADO 300 300 100 100 0.0 0% 6,500 6,500 2,295 2,295 2,295 0 0.00% 0 0.00% CENTRO EDUCATIVO 4 SEGUIMIENTO DE EGRESADOS 44 44 0 0 0.0 #¡DIV/0! 7,500 7,500 0 0 0 0 #¡DIV/0! 0 #¡DIV/0! ATENDIDO PARTICIPACION EN 5 PROYECTOS PRODUCTIVOS 2 2 1 0 0.5 100% 42,500 42,500 250 250 250 0 0.00% 0 0.00% FORO EMPRENDEDOR ALUMNO CON TAC 6 TRABAJO DE APOYO A LA COMUNIDAD 2,491 2,491 2,325 2,325 0.0 0% 3,500 3,500 2,273 2,273 2,273 0 0.00% 0 0.00% CONCLUIDO 7 ADECUACIÓN CURRICULAR REUNION REALIZADA 71 71 36 36 0.5 1% 188,486 188,486 62,091 62,091 55,356 6,736 10.85% 6,736 10.85% 8 MATERIALES DIDÁCTICOS LOTE DIDÁCTICO 29 29 8 5 2.5 33% 728,500 728,500 52,165 52,165 41,078 11,087 21.25% 11,087 21.25% ACCIONES DE 9 EVALUACIÓN DEL APRENDIZAJE 7 7 4 4 0.0 0% 500,600 500,600 194,567 194,567 9,860 184,707 94.93% 184,707 94.93% EVALUACION ACOMPAÑAMIENTO PSICOPEDAGÓGICO -

Territorial Grids of Oecd Member Countries Découpages Territoriaux

TERRITORIAL GRIDS OF OECD MEMBER COUNTRIES DÉCOUPAGES TERRITORIAUX DES PAYS MEMBRES DE L’OCDE Directorate of Public Governance and Territoral Development Direction de la Gouvernance Publique et du Développement Territorial 1 TERRITORIAL GRIDS OF OECD MEMBER COUNTRIES Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Tables Table/Tableau 1. Territorial levels for statistics and indicators / Niveaux territoriaux pour les statistiques et indicateurs ................................................................ 3 Table/Tableau 2. Area and population of Territorial levels 2 / Superficie et population des niveaux territoriaux .......................................................................... 4 Table/Tableau 3. Area and population of Territorial levels 3 / Superficie et populationdes niveaux territoriaux 3 ........................................................................ 5 Figures Australia / Australie ....................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche .......................................................................................................................... 9 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................... 10 Canada ........................................................................................................................................