Sounding Appalachian: /Ai/ Monophthongization, Rising Pitch Accents, and Rootedness Paul E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. R-Influence on Vowels

4. R-influence on vowels Before you study this chapter, check whether you are familiar with the following terms: allophone, centring diphthong, complementary distribution, diphthong, distribution, foreignism, fricative, full vowel, GA, hiatus, homophone, Intrusive-R, labial, lax, letter-to-sound rule, Linking-R, low-starting diphthong, minimal pair, monophthong, morpheme, nasal, non-productive suffix, non-rhotic accent, phoneme, productive suffix, rhotic accent, R-dropping, RP, tense, triphthong This chapter mainly focuses on the behaviour of full vowels before an /r/, the phonological and letter-to-sound rules related to this behaviour and some further phenomena concerning vowels. As it is demonstrated in Chapter 2 the two main accent types of English, rhotic and non-rhotic accents, are most easily distinguished by whether an /r/ is pronounced in all positions or not. In General American, a rhotic accent, all /r/'s are pronounced while in Received Pronunciation, a non-rhotic variant, only prevocalic ones are. Besides this, these – and other – dialects may also be distinguished by the behaviour of stressed vowels before an /r/, briefly mentioned in the previous chapter. To remind the reader of the most important vowel classes that will be referred to we repeat one of the tables from Chapter 3 for convenience. Tense Lax Monophthongs i, u, 3 , e, , , , , , , 1, 2 Diphthongs and , , , , , , , , triphthongs , Chapter 4 Recall that we have come up with a few generalizations in Chapter 3, namely that all short vowels are lax, all diphthongs and triphthongs are tense, non- high long monophthongs are lax, except for //, which behaves in an ambiguous way: sometimes it is tense, in other cases it is lax. -

He Went in a Private, Came out a Lt. Colonel

Are storytellers Gregg Allman born to tell Bearing the Cross big whoppers? Page 4 Page 6 Home of MIKE KILTS 132nd YEAR - NO. 48 Tuesday, JUNE 13, 2017 TWO SECTIONS - 75¢ PER COPY The German Buchenwald Prison Camp Auburntown native Major Frank E. Willard of the 738th Field Artillery Batt alion’s penned this article for The Cannon Courier in 1945. This was his account of the Buchenwald concentration camp, which was liberated by American forces at 3:15 p.m. on April 11, 1945. Willard visited the camp the morning of April 22, 1945. I will tell you what I saw yesterday with my own eyes because I was there in person. It was no propaganda, no unoffi cial newspaper, radio or magazine reports — just a plain fact. On my way home from London, England, I visited, to- gether with two lieutenant colonels, Hitler’s Buchenwald concentration camp, which is located about fi ve miles southwest of Weimar, Germany. This has been described by many prisoners as one of the “bett er” camps. We were met at the entrance of this camp by one who had formerly been an internee of this camp, a Czech civil- ian prisoner. He spoke English sparingly, but there was litt le need for him to speak at all, as each scene spoke for itself. He off ered his assistance as a guide. We assured him that we were very appreciative of his service and as our time was limited, to show us only a few of the scenes, and to be brief. Our guide stated that during the past six years, of 21 nationalities, including British and American, 51,000 had been murdered and one million died a natural death (I found out later what he meant by natural death). -

Variation in Form and Function in Jewish English Intonation

Variation in Form and Function in Jewish English Intonation Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Steindel Burdin ∼6 6 Graduate Program in Linguistics The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Brian D. Joseph, Advisor Professor Cynthia G. Clopper Professor Donald Winford c Rachel Steindel Burdin, 2016 Abstract Intonation has long been noted as a salient feature of American Jewish English speech (Weinreich, 1956); however, there has not been much systematic study of how, exactly Jewish English intonation is distinct, and to what extent Yiddish has played a role in this distinctness. This dissertation examines the impact of Yiddish on Jewish English intonation in the Jewish community of Dayton, Ohio, and how features of Yiddish intonation are used in Jewish English. 20 participants were interviewed for a production study. The participants were balanced for gender, age, religion (Jewish or not), and language background (whether or not they spoke Yiddish in addition to English). In addition, recordings were made of a local Yiddish club. The production study revealed differences in both the form and function in Jewish English, and that Yiddish was the likely source for that difference. The Yiddish-speaking participants were found to both have distinctive productions of rise-falls, including higher peaks, and a wider pitch range, in their Yiddish, as well as in their English produced during the Yiddish club meetings. The younger Jewish English participants also showed a wider pitch range in some situations during the interviews. -

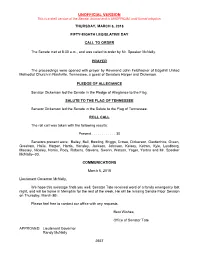

UNOFFICIAL VERSION This Is a Draft Version of the Senate Journal and Is UNOFFICIAL Until Formal Adoption

UNOFFICIAL VERSION This is a draft version of the Senate Journal and is UNOFFICIAL until formal adoption. THURSDAY, MARCH 8, 2018 FIFTY-EIGHTH LEGISLATIVE DAY CALL TO ORDER The Senate met at 8:30 a.m., and was called to order by Mr. Speaker McNally. PRAYER The proceedings were opened with prayer by Reverend John Feldhacker of Edgehill United Methodist Church in Nashville, Tennessee, a guest of Senators Harper and Dickerson. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Senator Dickerson led the Senate in the Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag. SALUTE TO THE FLAG OF TENNESSEE Senator Dickerson led the Senate in the Salute to the Flag of Tennessee. ROLL CALL The roll call was taken with the following results: Present . 30 Senators present were: Bailey, Bell, Bowling, Briggs, Crowe, Dickerson, Gardenhire, Green, Gresham, Haile, Harper, Harris, Hensley, Jackson, Johnson, Kelsey, Ketron, Kyle, Lundberg, Massey, Niceley, Norris, Pody, Roberts, Stevens, Swann, Watson, Yager, Yarbro and Mr. Speaker McNally--30. COMMUNICATIONS March 6, 2018 Lieutenant Governor McNally, We hope this message finds you well. Senator Tate received word of a family emergency last night, and will be home in Memphis for the rest of the week. He will be missing Senate Floor Session on Thursday, March 8th. Please feel free to contact our office with any requests. Best Wishes, Office of Senator Tate APPROVED: Lieutenant Governor Randy McNally 2657 THURSDAY, MARCH 8, 2018 -- 58TH LEGISLATIVE DAY Thursday, March 8, 2018 Lieutenant Governor Randy McNally 425 5th Avenue North Cordell Hull Building, Suite 700 Nashville, TN 37243 Dear Lieutenant Governor McNally: Please excuse my absence from Session today (Thursday, March 8, 2018). -

Tennessee Symbols and Honors

514 TENNESSEE BLUE BOOK Tennessee Symbols And Honors Official Seal of the State Even before Tennessee achieved statehood efforts were made by local govern- mental organizations to procure official seals. Reliable historians have assumed that as early as 1772 the Articles of the Agreement of the Watauga Association authorized the use of a seal. The Legislature of the state of Franklin, by an official act, provided “for procuring a Great Seal for this State,” and there is also evidence that a seal was intended for the Territory South of the River Ohio. The secretary of that territory requested the assistance of Thomas Jefferson in March, 1792, in “suggesting a proper device” for a seal. There is no direct evidence, however, that a seal was ever made for any of these predecessors of Tennessee. When Tennessee became a state, the Constitution of 1796 made provision for the preparation of a seal. Each subsequent constitution made similar provisions and always in the same words as the first. This provision is (Constitution of 1796, Article II, Section 15; Constitution of 1835, Article III, Section 15; Constitution of 1870, Article III, Section 15) as follows: There shall be a seal of this state, which shall be kept by the governor, and used by him officially, and shall be called “The Great Seal of the State of Tennessee.” In spite of the provision of the Constitution of 1796, apparently no action was taken until September 25, 1801. On that date committees made up of members from both the Senate and the House of Representatives were appointed. -

Palatals in Spanish and French: an Analysis Rachael Gray

Florida State University Libraries Honors Theses The Division of Undergraduate Studies 2012 Palatals in Spanish and French: An Analysis Rachael Gray Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] Abstract (Palatal, Spanish, French) This thesis deals with palatals from Latin into Spanish and French. Specifically, it focuses on the diachronic history of each language with a focus on palatals. I also look at studies that have been conducted concerning palatals, and present a synchronic analysis of palatals in modern day Spanish and French. The final section of this paper focuses on my research design in second language acquisition of palatals for native French speakers learning Spanish. 2 THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PALATALS IN SPANISH AND FRENCH: AN ANALYSIS BY: RACHAEL GRAY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Modern Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: 3 Spring, 2012 The members of the Defense Committee approve the thesis of Rachael Gray defended on March 21, 2012 _____________________________________ Professor Carolina Gonzaléz Thesis Director _______________________________________ Professor Gretchen Sunderman Committee Member _______________________________________ Professor Eric Coleman Outside Committee Member 4 Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 5 0. -

A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall [email protected]

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons HON499 projects Honors Program Fall 11-29-2017 A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the Other Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Wall, Ryan, "A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect" (2017). HON499 projects. 12. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/honors_projects/12 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in HON499 projects by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Jawn by Any Other Name: A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Philadelphia Dialect Ryan Wall Honors 499 Fall 2017 RUNNING HEAD: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF THE PHILADELPHIA DIALECT 2 Introduction A walk down Market Street in Philadelphia is a truly immersive experience. It’s a sensory overload: a barrage of smells, sounds, and sights that greet any visitor in a truly Philadelphian way. It’s loud, proud, and in-your-face. Philadelphians aren’t known for being a quiet people—a trip to an Eagles game will quickly confirm that. The city has come to be defined by a multitude of iconic symbols, from the humble cheesesteak to the dignified Liberty Bell. But while “The City of Brotherly Love” evokes hundreds of associations, one is frequently overlooked: the Philadelphia Dialect. -

Analogy in the Emergence of Intrusive-R in English MÁRTON SÓSKUTHY University of Edinburgh 2

Analogy in the emergence of intrusive-r in English MÁRTON SÓSKUTHY University of Edinburgh 2 ABSTRACT This paper presents a novel approach to the phenomenon of intrusive-r in English based on analogy. The main claim of the paper is that intrusive-r in non-rhotic ac- cents of English is the result of the analogical extension of the r∼zero alternation shown by words such as far, more and dear. While this idea has been around for a long time, this is the first paper that explores this type of analysis in detail. More specifically, I provide an overview of the developments that led to the emergence of intrusive-r and show that they are fully compatible with an analogical approach. This includes the analysis of frequency data taken from an 18th century corpus of English compiled specifically for the purposes of this paper and the discussion of a related development, namely intrusive-l. To sharpen the predictions of the analog- ical approach, I also provide a mathematically explicit definition of analogy and run a computer simulation of the emergence of the phenomenon based on a one million word extract from the 18th century corpus mentioned above. The results of the simulation confirm the predictions of the analogical approach. A further advantage of the analysis presented here is that it can account for the historical development and synchronic variability of intrusive-r in a unified framework. 3 1 INTRODUCTION The phenomenon of intrusive-r in various accents of English has inspired a large number of generative analyses and is surrounded by considerable controversy, mainly because of the theoretical challenges that it poses to Optimality The- ory and markedness-based approaches to phonology (e.g. -

Student and Educator Beliefs on an English As a Lingua Franca Classroom Framework

Student and Educator Beliefs on an English as a Lingua Franca Classroom Framework By Florence Pattee A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in TESOL University of Wisconsin- River Falls 2020 BELIEFS ON AN ELF FRAMEWORK 2 Abstract The ways in which students use English to communicate has evolved. Many students around the world now use English to communicate as a lingua franca with other non-native speakers. In order to meet the needs of their students and help them achieve their goals, teachers need to be aware of not only how their students are using English but the beliefs about English language learning that they are bringing into the classroom. Further, teachers must be aware of the extent to which their own beliefs are aligned with those of their students. This study of 86 students at four language centers in Malaysia, along with their 18 instructors, investigated the extent to which student beliefs align with an English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) framework, and the degree to which teachers share those beliefs and are aware of them. Students were asked to respond to 15 statements about their beliefs on the role of culture in language learning, frequency of error correction, native-speaker models and interlocutor beliefs. The teacher survey similarly asked teachers to respond to 10 statements about their beliefs and their awareness of student beliefs, while setting up three direct comparisons between what the students believe and what the teachers think their students believe. The study found that teacher beliefs largely seemed supportive of an ELF approach. -

A SUMMARY of SWANA HISTORY August 2012

A SUMMARY OF SWANA HISTORY August 2012 Advancing the practice of environmentally and economically sound management of municipal solid waste in North America. Guiding Principle: Local government is responsible for municipal solid waste management, but not necessarily the ownership and/or operation of municipal solid waste management systems. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF SWANA – 1962 TO PRESENT CHAPTERS – Foundation of the Association GOVERNANCE and MANAGEMENT TECHNICAL PROGRAMS SWANA PROGRAMS AND MEMBERSHIP SERVICES TODAY INTRODUCTION: SWANA Today ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF PROGRAMS AND SERVICES (Note: Appendices and Attachments are in a separate document) INTRODUCTION As part of the celebration of the Associations 50th Anniversary, we have put together a summary of the history that makes the Association the viable and dynamic organization it is today. Each of us knows, in our own personal and professional lives, what the Association means to us – how it has contributed to each personal development, and impacted each career, through networking, training, research & development, and advocacy work, to name a few. Being there to provide the latest information and support - the foremost “community” in our ever growing industry. The formation, development and growth of the Association – starting as the Governmental Refuse Collection and Disposal Association (GRCDA) – and later becoming The Solid Waste Association of North America (SWANA), is presented in this document. The history for the years 1960 through 1996 was authored by Lanny Hickman, the Executive Director of the Association from 1978 to 1996 – and is available in SWANA’s On-Line Library in its entirety. The information provided by Lanny for those years was utilized for this summary history – and the information for the following fifteen years, until present, was completed by Associate Director, Kathy Callaghan, with the assistance of SWANA Staff. -

Review Article

Studies in the Linguistic Sciences Volume 29, Number 2 (Fall 1999) REVIEW ARTICLE Christina Y. Bethin. Slavic Prosody: Language Change and Phonological Theory. (Cambridge Studies in Linguistics, 86.) New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Pp. xvi + 349. Price: $69.95. ISBN 0521591481. Frank Y. Gladney University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign [email protected] Professor Bethin' s ambitious and challenging book has a chapter titled 'The syl- lable in Slavic: form and function' (12-111), one titled 'Beyond the syllable: prominence relations' (112-87), and a miscellany titled 'Theoretical considera- tions' (188-265). They are preceded by a preface and introduction (xii-11) and followed by end notes (266-301) and an imposing list of references (302-46). The Slavic of her title includes Proto-Slavic (up to the middle of our first millennium), Common Slavic (6th-8th centuries), and Late Common Slavic (9th- 12th centu- ries). Chapter 1 is concerned with the development of diphthongal syllable rhymes. Displaying an encyclopedic knowledge of the Slavistic literature, Bethin reviews the history of how oral, nasal, and liquid diphthongs were monoph- thongized, recasting it in the framework of autosegmental phonology. These syl- lable rhymes, she argues, were shaped by the interplay of various constraints on syllable structure. 'Proto-Slavic had a front/back, a high/nonhigh, and a long/short opposition in vowels', quite traditionally begins the section titled 'Monophthongization' (39). These features defined a square system with four vowels: [+high, -back] i, [+high, +back] u, [-high, -back] e, and [-high, +back] o. Bethin and many other Slavists use the more familiar symbols e, o, and a for the nonhigh vowels, but I find e and a useful as a reminder that Proto-Slavic fused PIE *o and *a into a sin- gle nonhigh back vowel and so converted the inherited triangular system with three degrees of opening to a square system with two. -

A History of English Phonology

A History of English Phonology Charles Jones >Pt> PPP PPP LONGMAN LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents Preface ix Acknowledgements xi 1 Aims, methods and model i 1.1 Aims i 1.2 Method 4 1.3 Model 5 2 The Early English period: the beginnings to the thirteenth century 9 2.1 The nature of the data 9 2.2 Vowel lengthening processes in Old English 15 2.2.1 Compensatory lengthening 18 2.2.2 Lengthenings in more general fricative contexts • 19 2.2.3 Stressed vowel lengthening in nasal sonorant contexts 21 2.2.4 Lengthening in nasal and non-nasal sonorant contexts: Late Old English hontorganic lengthening 24 2.2.5 The reconstruction of vowel length 26 2.2.6 The date of the homorganic lengthening process 29 2.3 Diphthongization processes in Old English 33 2.3.1 Old English Breaking 38 2.3.2 Breaking of long stressed vowels 45 2.3.3 Causes of this diphthongization in pre-[x], [r], [1] contexts 47 2.3.4 Did this diphthongization ever really happen? 49 VI CONTENTS 2.3.5 Exceptions to the Breaking process 51 2.3.6 Breaking in other fricative contexts 54 2.4 Monophthongization processes: Late Old English developments to Breaking-produced diphthongs 58 2.4.1 The instability of contextually derived alternations 61 2.4.2 Monophthongization and raising as a unified process 62 2.4.3 Middle English monophthongization processes 64 2.4.4 The Middle English development of the Old English [eo] diphthong 66 2.4.5 Special Kentish developments: syllabicity shifting - 68 2.5 Vowel harmony processes in Old English 73 2.5.1 Backness/labial harmony two: Old English Back Mutation