Jennie C. Jones Interviewed by Jared Quinton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circuition: Concerto for Jazz Guitar and Orchestra

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2021 CIRCUITION: CONCERTO FOR JAZZ GUITAR AND ORCHESTRA Richard Alan Robinson University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2021.166 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Robinson, Richard Alan, "CIRCUITION: CONCERTO FOR JAZZ GUITAR AND ORCHESTRA" (2021). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 178. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/178 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Analytic, Descriptive, and Prescriptive Components of Evolving Jazz: a New Model Based on the Works of Brad Mehldau

Analytic, Descriptive, and Prescriptive Components of Evolving Jazz: A New Model Based on the Works of Brad Mehldau Mark Edward Baynes An exegesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Auckland 2015 ii Abstract Jazz has steadily evolved from its inception in the late 19th century to the present. As is the case for other genres, musicological analytic research on jazz evolution has lagged behind its practice; consequently, there is a paucity of in-depth descriptive and analytic research on the music of recent innovators. Among the most recent examples of this evolution, the works of Brad Mehldau as a solo/ensemble pianist and as a composer arguably embody some of the most compelling innovations in the field. Non-academically oriented jazz writers and fans have consistently assigned these works vanguard status, but Mehldau’s output has not yet been sufficiently examined to prescribe performance methods. This exegesis contains (1) descriptive analysis of improvisation contained within a broad cross-section of Mehldau’s music; (2) definition of a new analytical lexicon derived from a holistic study of consonance, dissonance, and research into perceived motivation in music; and (3) prescriptive musical tools relating to consonance and dissonance that have informed the researcher’s performance. iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my special thanks to Dr David Lines, Associate Professor W. Dean Sutcliffe, Dr Davinia Caddy, Kevin Field, Dr Mark Kramer, Gary Burton, Jo Shum, Steve Harvie, Alex Freer, Tom Dennison, Dixon Nacey, Nick Marsh, Jason Orme, Chrissie Hart, Hadyn Godfrey, Chris Mason-Battley, Phil Broadhurst, Kim Paterson, Tom Rainey, Mike Booth and Stephen Morton-Jones. -

Malcolm Braff's Approach to Rhythm for Improvisation

Malcolm Braff’s Approach to Rhythm for Improvisation: Definition, Analysis and Aesthetic Daniel Jacobus Steyn de Wet A dissertation submitted to the faculty of humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MMUS. Johannesburg 2017 Plagiarism Declaration 1. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to use another’s work and to pretend that it is one’s own. 2. I have used the author date convention for citation and referencing. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this thesis from the work or works of other people has been acknowledged through citation and reference. 3. The essay is my own work. 4. I have not allowed and will not allow anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. _______________________ _________________________ Signature Date Human Research Ethics Clearance (non-medical) Certificate Number: 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my friends and family for the support they have shown through this time. I further thank the various supervisors and co-supervisors who have at some point had some level of input into this study. On the practical side of my study I thank Malcolm Ney for the high level of classical training that I have received. I thank Andre Petersen for his input into the jazz specific aspects of my performance training. Special thanks to Dr. Carlo Mombelli for the training I received in his ensembles and at his home with regard to beautiful and improvised music. Thanks also go to the supervisors for the majority of my proposal phase Dr. -

Naus Beyfuncharm

Table of Contents CD Index · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 7 Preface · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 9 Introduction · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 10 Functional vs. non-functional · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 11 PART I Elements of predictability · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 13 Functional fundamental characteristics · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 14 Harmonic · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 14 • Harmonic patterns • Cadences • Deceptive resolution • Line cliches • Harmonic progression Key areas · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 20 Harmonic phrase · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 21 Harmonic rhythm · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 22 Rhythmic style · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · 23 Melody -

Jan Patočka and the Heritage of Phenomenology CONTRIBUTIONS to PHENOMENOLOGY

Jan PatoČka and the heritage of Phenomenology ContriBUtionS TO Phenomenology in CooPERATION With the Center for adVanCed reSearCh in Phenomenology Volume 61 Series editors: Nicolas de Warren, Wellesley College, ma, USa Dermot Moran, University College dublin, ireland editorial Board: Lilian Alweiss, trinity College dublin, ireland Elizabeth Behnke, ferndale, Wa, USa Rudolf Bernet, Husserl-Archief, katholieke Universiteit leuven, Belgium David Carr, emory University, ga, USa Chan-Fai Cheung, Chinese University hong kong, China James Dodd, new School University, ny, USa Lester Embree, florida atlantic University, fl, USa Alfredo Ferrarin, Università di Pisa, italy Burt Hopkins, Seattle University, Wa, USa José Huertas-Jourda, Wilfrid laurier University, Canada Kwok-Ying Lau, Chinese University hong kong, China Nam-In Lee, Seoul national University, korea Dieter Lohmar, Universität zu köln, germany William R. McKenna, miami University, oh, USa Algis Mickunas, ohio University, oh, USa J.N. Mohanty, temple University, Pa, USa Junichi Murata, University of tokyo, Japan Thomas Nenon, the University of memphis, tn, USa Thomas M. Seebohm, Johannes gutenberg-Universität, germany Gail Soffer, rome, italy Anthony Steinbock, Southern illinois University at Carbondale, il, USa Shigeru Taguchi, yamagata University, Japan Dan Zahavi, University of Copenhagen, denmark Richard M. Zaner, Vanderbilt University, tn, USa Scope the purpose of the series is to serve as a vehicle for the pursuit of phenomenological research across a broad spectrum, including cross-over developments with other fields of inquiry such as the social sciences and cognitive science. Since its establishment in 1987, Contributions to Phenomenology has published nearly sixty titles on diverse themes of phenomenological philosophy. in addition to welcoming monographs and collections of papers in established areas of scholarship, the series encourages original work in phenomenology. -

MUS-2650: Jazz Theory II 1

MUS-2650: Jazz Theory II 1 MUS-2650: JAZZ THEORY II Cuyahoga Community College Viewing: MUS-2650 : Jazz Theory II Board of Trustees: May 2018 Academic Term: Fall 2018 Subject Code MUS - Music Course Number: 2650 Title: Jazz Theory II Catalog Description: Second level study of theoretical foundations of jazz. Includes diatonic and chromatic harmony, harmonic embellishment and substitution, voicings, rhythm, blues progressions and forms, phrase analysis, lyric import and analysis of transcribed solos and compositions from jazz repertoire. Credit Hour(s): 2 Lecture Hour(s): 2 Lab Hour(s): 0 Other Hour(s): 0 Requisites Prerequisite and Corequisite MUS-1650 Jazz Theory I. Outcomes Course Outcome(s): Apply elements of Jazz Theory to analyze and improvise on the standards from the American Songbook for performance, composition and arranging in multiple genres. Essential Learning Outcome Mapping: Critical/Creative Thinking: Analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information in order to consider problems/ideas and transform them in innovative or imaginative ways. Objective(s): 1. Notate and identify diminished 7th chords used in a diatonic context, and use them appropriately in a chord progression. 2. Synthesize deceptive resolutions of secondary dominants, and use them appropriately in a chord progression; 3. Synthesize the special function dominant 7th chords, and use them appropriately in a chord progression. 4. Synthesize contiguous dominant motion, and use it appropriately in a chord progression. 5. Synthesize modal interchange from all possible modal sources, and use it appropriately in a chord progression. 6. Synthesize harmonic constant structure, and use it appropriately. 7. Compose using ostinato and pedal point. 8. Compose melodies, bass lines, and chord progressions in modal tonic systems, using popular song forms. -

Gary Burton Course

Gary Burton Improvisation Course Intro Improvisers usually get started by listening to records and trying to copy their favourite players. We also learn from other musicians and from just experimenting as much as we can. As a result pretty much everyone's knowledge of improvisation is not only incomplete, but also has a perspective unique to each player's learning experience. At some point along the way, this haphazard way of learning isn't enough, and the intermediate level improviser needs to learn more about the techniques and mental processes that take place in improvising. In this course, we will explore three areas of importance for improvising. One is technical information—how improvisers deal with harmony, melodic construction, and execution in ways that are different from playing written music. Two is learning how to analyse and understand compositions from the point of view of the improviser in order to play meaningful solos that capture the important elements of the songs we use as the basis for improvising. And three is learning how the mental processes function in improvising, again different from performing written music, and key to being an effective improviser. We will also take a look at a lot of ancillary topics ranging from use of dynamics to theme development, chromaticism, and accompanying other soloists, among others that are important for the improviser to understand and use properly. By the end of the course, you will have a well-rounded understanding of improvisation and be able to assess your strengths and areas to work on in future practicing and how to go about it. -

Speakingofjazz.Pdf

Speaking of Jazz: Essays & Attitudes Speaking of Jazz: Essays & Attitudes —Ed Byrne Copyright © Ed Byrne 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For more information, contact the author at [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface vii Introduction ix CHAPTER 1. Concepts 1 2. Improvisation 49 3. Ear Training/Transcription 69 4. Blues 75 5. Practicing Jazz Improvisation 85 6. Practicing Formulas 91 7. Practicing Scales and Modes 109 8. Rhythm Instruments 131 9. Attitudes 151 10. Theory 173 11. Harmony 179 12. Notation 201 13. Analysis 213 14. Composing/Arranging 235 15. Band Leading 249 16. Brass 265 v vi In an extemporaneous art form such as jazz, how one thinks has a direct and profound impact on performance. PREFACE This book constitutes my advice from a lifetime as jazz artist and educator on how to think and prepare for jazz performance. What follows is a series of essays written extemporaneously in response to students’ questions. Since no documentation is offered, they do not constitute scholarly dissertations. While topics have been grouped together in rough categorical sequence, this is not a text or method book; and they do not constitute complete studies. It is my hope, however, that this collection will inform, inspire, and provoke aspiring jazz performers and educators alike. \\ vii viii Know your story and be able to deliver it in a powerful personal style. -

Theory Advanced Group JAZZ CLINIC

Summer clinics Halewynstichting 2015 – classes of Maarten Weyler Questions? Send a mail to [email protected] Theory advanced group JAZZ CLINIC DWORP 2015 This summer also: Pop clinic 23 – 28 august JAZZ CLINIC 2015 THEORY ADVANCED GROUP 1 Summer clinics Halewynstichting 2015 – classes of Maarten Weyler Questions? Send a mail to [email protected] 1. My Romance In the first class we give you an overview of what you should know to understand a composition such as “My Romance” (R. Rodgers & L. Hart). A good start is always the lyrics: My Romance doesn't have to have a moon in the sky My Romance doesn't need a blue lagoon standing by No month of May, no twinkling stars No hide away, no soft guitars My Romance doesn't need a castle rising in Spain Nor a dance to a constantly surprising refrain Wide awake I can make my most fantastic dreams come true My Romance doesn't need a thing but you We continue with the melody and look at its structure, its organisation. Ask yourself questions such as: - What is the motive (smallest melodic cellula) - What is the first phrase? - How is this futher developed? - What is the structure of the first sixteen bars? Things you should know before the analysis: • What is the tonality? (1) • What are the diatonic chords? (2) • Which chords are diatonic, which aren’t? (3) • Is the melody diatonic? (4) • What are the related chords to be expected, such as for Secondary Dominants and what is the added value of these chords? (5) JAZZ CLINIC 2015 THEORY ADVANCED GROUP 2 Summer clinics Halewynstichting 2015 – classes of Maarten Weyler Questions? Send a mail to [email protected] • What are the related tonalities to be expected? What are the expected parallel chords and what is their added value? (6) Some answers: 1) The song is written in C major 2) The diatonic chords: 3) Chords which are ‘non-diatonic’: Most of the chords are diatonic, which you can see at their roman numerals. -

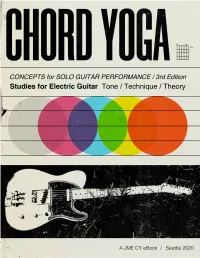

From 'Concepts for Solo Guitar Performance

Part I Studies for electric guitar Tone - Technique - Theory Pitch, texture and dynamics 1. Sound consistency ……………………………………………………………………………………….…....1 2. Synchronizing left and right hand …………………...….………………………………........2 Posture Fretting hand permutations / tone production Rhythmic and dynamic balance Legato playing ‘Two-line’ scale exercises Chordal playing: - picking patterns / permutations / dynamics - posture / preparing notes - block chords and dynamic control - adding chord shapes - ‘blurring the lines’ - combining single-notes and chordal playing Studies for electric guitar ‘Stella Watches The Stars’ …………………………………………………….………………………......7 ‘Nioma’ - blues riffs in DADGAD tuning ‘Chet’s Dream’ ‘Slow Dancing’ - a John Mayer-inspired guitar stroll ‘Akane’ ‘How to Pass A Blue Monk’ - jazz blues study Applied Music Theory 1. Jazz blues analysis …………………………………………………………...…....……….......…............... 16 2. ‘Tele moves’ - licks and riffs, triad inversions 3. ‘Neo soul flares’ - lick concepts by Chalmers ‘Spanky’ Alford 4. Arranging grooves for solo guitar 5. Arranging for solo guitar: basics ……………………………..………………………..................... 23 - melodic phrases and harmonic progressions - chord-melody: ‘gospel chords’ and (re)harmonization ideas - solo guitar arrangement: ‘Amazing Grace’ 6. ‘Shenandoah’ - Bill Frisell (solo): transcription & analysis ….......................... 27 © JME / CY, Inc. 2020 1 Tone & technique Pitch, texture and dynamics 1. Sound consistency Ex. 1 A7 A 7à13 E7 A7 b 3 œ 3 # œ œn œ œ œ œ j ## 4 œ œ œ œn œ œ œ œ œ œ# œ. œ# 3 3 œ . Ó V 4 œn 3 œb 3 œn œ# j nœ 3 œ hold bend œ œ. 3 3 3 œ 3 3 3 3 full H H j 5 0 12 j 8 5 7 12 5 6 5 11 13 13 13 13 (11) 9 5 6 5 4 11 9 5 0 10 11 0 0 Ó 0 The term // tone [tōn] // can be defined as your perception of the interplay of pitch, texture and dynamics. -

Concepts for Solo Guitar Performance 2Nd Edition

Concepts for Solo Guitar Performance 2nd Edition © Juju Music Edition - 2018 CONCEPTS FOR SOLO GUITAR PERFORMANCE By Jan Jakut 2nd Edition Juju Music Edition Seattle COPYRIGHT © 2018, JUJU MUSIC EDITION, INC. PUBLISHED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Juju Music Edition, Inc., [email protected]. Cover Art © Julian Strait www. madebyshore. com About the Author Jan Jakut is a musician and music publisher living in Seattle, Washington. He received his undergraduate training in Jazz Guitar at the University of Mainz - School of Music (Germany) and studied for his master’s degree in Jazz and Improvised Music at the University of Washington - School of Music. He is a multiple published author with Schott Music International and has received awards and scholarships, among them the A. Reynolds Endowed Scholarship in Music. Based on his published work and his solo guitar performances, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services granted him permanent residency with an EB-1 visa, addressing extraordinary abilities in the arts. With Juju Music Edition he publishes transcriptions and educational material for solo guitar to sustain and propel the rich heritage of American Popular Music by making its idiom and general body of knowledge available for current and future students of music in the US and abroad. Since 2015 he performs on the West Coast and frequently teaches at institutions like the California Jazz Conservatory, Berkeley. -

MUJS 4610 Syllabus

MUJS 4610, Jazz Arranging III General Information MUJS 4610.001, Jazz Arranging (3 credits, offered only in the fall semester) Class Time – M 9:00-10:40, W 9:00 – 9:50 Professor: Richard DeRosa [email protected] [email protected] 973-953-1471 Prerequisites: MUJS 3620 with a grade of A or B, and the Arranging Continuation Exam. The ACE is given concurrently with final MUJS 3620 reviews, and by appointment prior to the beginning of fall semester. Reference texts: The student is expected to have immediate access to texts from MUJS 3610 and 3620 and Inside The Score (Rayburn Wright). Course description: MUJS 4610 is required of all graduate jazz majors, and undergraduate arranging majors. This course explores the basic textures of writing (monophonic, polyphonic, and homophonic) with a deeper analysis of melodic composition, contrapuntal and harmonic styles and techniques, and orchestration “across” the horn sections. The assignments below will occur in the order of presentation. All are designed to instill a focus on particular techniques that may be applied to personal creative projects. Depending on the complexity of the assignment, some may require at least two weeks to complete. The class progression will be determined accordingly. Most likely, the Blues Harmony assignments will not be realized until next semester. Those lessons are also found in the 4620 syllabus and in Blackboard. Monophonic Texture Lesson 1: Melodic composition 1 - “Improv” unison/octaves band soli. Listening/Analysis Examples: “I’d Rather Lead a Band”, “Long Way on a Blues” Assignment: take a medium or fast tempo and write a modern melodic line for tutti horns.