The Architecture of Schools in the Arctic from 1950 to 2007 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Update: March 23, 2020 Current Procedure

PUBLIC UPDATE: MARCH 23, 2020 Over the weekend, Town Administration, Staff, & Leadership have been involved in extensive communication and planning with our regional Government of the Northwest Territories personnel and administration. While we are responding to the evolving situation, our main focus has been on our procedure to how Inuvik will receive, monitor, house, & feed those returning to Inuvik from one of the smaller regional communities or those who do not have an adequate space at home to fulfill the requirements for the 14 days of required self-isolation. As you are now aware, the Chief Health Officer and the Government of the Northwest Territories now requires every person entering the Territory (including residents) to self-isolate for 14 days. Further to this, the GNWT requires those required to self-isolate to do so in one of the larger designated centres: Hay River, Yellowknife, Inuvik or Fort Smith. CURRENT PROCEDURE FOR THOSE ENTERING INUVIK BY ROAD OR BY AIR All persons returning to Inuvik from outside the Territory, by road or by air are now being screened at the point of entry. Whether you enter Inuvik via the Dempster Highway or the Inuvik Airport, you will be screened and directed in the following ways: 1. If you have not already, you are required to complete and submit a self-isolation plan to the GNWT. Link to Self-Isolation Plan Form Here. 2. If you are an Inuvik resident and are able to self-isolate at home, you will be directed to proceed directly to your home and stay there for the 14-day duration following all protocols as required by the Chief Health Officer. -

Inuvialuit For

D_156905_inuvialuit_Cover 11/16/05 11:45 AM Page 1 UNIKKAAQATIGIIT: PUTTING THE HUMAN FACE ON CLIMATE CHANGE PERSPECTIVES FROM THE INUVIALUIT SETTLEMENT REGION UNIKKAAQATIGIIT: PUTTING THE HUMAN FACE ON CLIMATE CHANGE PERSPECTIVES FROM THE INUVIALUIT SETTLEMENT REGION Workshop Team: Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC), Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), Centre Hospitalier du l’Université du Québec (CHUQ), Joint Secretariat: Inuvialuit Renewable Resource Committees (JS:IRRC) Funded by: Northern Ecosystem Initiative, Environment Canada * This workshop is part of a larger project entitled Identifying, Selecting and Monitoring Indicators for Climate Change in Nunavik and Labrador, funded by NEI, Environment Canada This report should be cited as: Communities of Aklavik, Inuvik, Holman Island, Paulatuk and Tuktoyaktuk, Nickels, S., Buell, M., Furgal, C., Moquin, H. 2005. Unikkaaqatigiit – Putting the Human Face on Climate Change: Perspectives from the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. Ottawa: Joint publication of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Nasivvik Centre for Inuit Health and Changing Environments at Université Laval and the Ajunnginiq Centre at the National Aboriginal Health Organization. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Naitoliogak . 1 1.0 Summary . 2 2.0 Acknowledgements . 3 3.0 Introduction . 4 4.0 Methods . 4 4.1 Pre-Workshop Methods . 4 4.2 During the Workshop . 5 4.3 Summarizing Workshop Observations . 6 5.0 Observations. 6 5.1 Regional (Common) Concerns . 7 Changes to Weather: . 7 Changes to Landscape: . 9 Changes to Vegetation: . 10 Changes to Fauna: . 11 Changes to Insects: . 11 Increased Awareness And Stress: . 11 Contaminants: . 11 Desire For Organization: . 12 5.2 East-West Discrepancies And Patterns . 12 Changes to Weather . -

Community Resistance Land Use And

COMMUNITY RESISTANCE LAND USE AND WAGE LABOUR IN PAULATUK, N.W.T. by SHEILA MARGARET MCDONNELL B.A. Honours, McGill University, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Geography) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1983 G) Sheila Margaret McDonnell, 1983 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 DE-6 (3/81) ABSTRACT This paper discusses community resistance to the imposition of an external industrial socio-economic system and the destruction of a distinctive land-based way of life. It shows how historically Inuvialuit independence has been eroded by contact with the external economic system and the assimilationist policies of the government. In spite of these pressures, however, the Inuvialuit have struggled to retain their culture and their land-based economy. This thesis shows that hunting and trapping continue to be viable and to contribute significant income, both cash and income- in-kind to the community. -

Community Food Program Use in Inuvik, Northwest Territories James D Ford1*, Marie-Pierre Lardeau1, Hilary Blackett2, Susan Chatwood2 and Denise Kurszewski2

Ford et al. BMC Public Health 2013, 13:970 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/970 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Community food program use in Inuvik, Northwest Territories James D Ford1*, Marie-Pierre Lardeau1, Hilary Blackett2, Susan Chatwood2 and Denise Kurszewski2 Abstract Background: Community food programs (CFPs) provide an important safety-net for highly food insecure community members in the larger settlements of the Canadian Arctic. This study identifies who is using CFPs and why, drawing upon a case study from Inuvik, Northwest Territories. This work is compared with a similar study from Iqaluit, Nunavut, allowing the development of an Arctic-wide understanding of CFP use – a neglected topic in the northern food security literature. Methods: Photovoice workshops (n=7), a modified USDA food security survey and open ended interviews with CFP users (n=54) in Inuvik. Results: Users of CFPs in Inuvik are more likely to be housing insecure, female, middle aged (35–64), unemployed, Aboriginal, and lack a high school education. Participants are primarily chronic users, and depend on CFPs for regular food access. Conclusions: This work indicates the presence of chronically food insecure groups who have not benefited from the economic development and job opportunities offered in larger regional centers of the Canadian Arctic, and for whom traditional kinship-based food sharing networks have been unable to fully meet their dietary needs. While CFPs do not address the underlying causes of food insecurity, they provide an important service -

Sustainability in Iqaluit

2014-2019 Iqaluit Sustainable Community Plan Part one Overview www.sustainableiqaluit.com ©2014, The Municipal Corporation of the City of Iqaluit. All Rights Reserved. The preparation of this sustainable community plan was carried out with assistance from the Green Municipal Fund, a Fund financed by the Government of Canada and administered by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. Notwithstanding this support, the views expressed are the personal views of the authors, and the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and the Government of Canada accept no responsibility for them. Table of Contents Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION to Part One of the Sustainable Community Plan .........................................................2 SECTION 1 - Sustainability in Iqaluit ....................................................................................................3 What is sustainability? .............................................................................................................................. 3 Why have a Sustainable Community Plan? .............................................................................................. 3 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and sustainability .............................................................................................. 4 SECTION 2 - Our Context ....................................................................................................................5 Iqaluit – then and now ............................................................................................................................. -

An Ethnohistorical Review of Health and Healing in Aklavik, NWT, Canada

“Never Say Die”: An Ethnohistorical Review of Health and Healing in Aklavik, NWT, Canada by Elizabeth Cooper A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Native Studies University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Elizabeth Cooper Abstract The community of Aklavik, North West Territories, was known as the “Gateway to the North” throughout the first half of the Twentieth Century. In 1959, the Canadian Federal Government decided to relocate the town to a new location for a variety of economic and environmental reasons. Gwitch’in and Inuvialuit refused to move, thus claiming their current community motto “Never Say Die”. Through a series of interviews and participant observation with Elders in Aklavik and Inuvik, along with consultation of secondary literature and archival sources, this thesis examines ideas of the impact of mission hospitals, notions of health, wellness and community through an analysis of some of the events that transpired during this interesting period of history. Acknowledgements I would like to thank and honour the people in both Aklavik and Inuvik for their help and support with this project. I would like to thank my thesis committee, Dr. Christopher G Trott, Dr Emma LaRocque and Dr. Mark Rumel for their continued help and support throughout this project. I would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Dr. S. Michelle Driedger’s Research in Science Communication CIHR-CFI Research Lab, University of Manitoba Graduate Studies, University of Manitoba Faculty of Arts, University of Manitoba, Department of Native Studies and University of Manitoba Graduate Students Association, for making both the research and dissemination of results for this project possible. -

Tukitaaqtuq Explain to One Another, Reach Understanding, Receive Explanation from the Past and the Eskimo Identification Canada System

Tukitaaqtuq explain to one another, reach understanding, receive explanation from the past and The Eskimo Identification Canada System by Norma Jean Mary Dunning A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Faculty of Native Studies University of Alberta ©Norma Jean Mary Dunning, 2014 ABSTRACT The government of Canada initiated, implemented, and officially maintained the ‘Eskimo Identification Canada’ system from 1941-1971. With the exception of the Labrador Inuit, who formed the Labrador Treaty of 1765 in what is now called, NunatuKavat, all other Canadian Inuit peoples were issued a leather-like necklace with a numbered fibre-cloth disk. These stringed identifiers attempted to replace Inuit names, tradition, individuality, and indigenous distinctiveness. This was the Canadian governments’ attempt to exert a form of state surveillance and its official authority, over its own Inuit citizenry. The Eskimo Identification Canada system, E- number, or disk system eventually became entrenched within Inuit society, and in time it became a form of identification amongst the Inuit themselves. What has never been examined by an Inuk researcher, or student is the long-lasting affect these numbered disks had upon the Inuit, and the continued impact into present-day, of this type of state-operated system. The Inuit voice has not been heard or examined. This research focuses exclusively on the disk system itself and brings forward the voices of four disk system survivors, giving voice to those who have been silenced for far too long. i PREFACE This thesis is an original work by Norma Dunning. The research project, of which this thesis is a part, received research ethics approval from the University of Alberta Research Ethics Board, Project Name: “Tukitaaqtuq (they reach understanding) and the Eskimo Identification Canada system,” PRO00039401, 05/07/2013. -

The Harvest of Beluga Whales in Canada's Western Arctic: Hunter

ARCTIC VOL. 55, NO. 1 (MARCH 2002) P. 10–20 The Harvest of Beluga Whales in Canada’s Western Arctic: Hunter-Based Monitoring of the Size and Composition of the Catch LOIS A. HARWOOD,1 PAMELA NORTON,2 BILLY DAY3 and PATRICIA A. HALL4 (Received 9 July 1998; accepted in revised form 23 May 2001) ABSTRACT. Hunter-based beluga monitoring programs, in place in the Mackenzie Delta since 1973 and in the Paulatuk, Northwest Territories, area since 1989, have resulted in collection of data on the number of whales harvested and on the efficiency of the hunts. Since 1980, data on the standard length, fluke width, sex, and age of the landed whales have also been collected. The number of belugas landed each year averaged 131.8 (SD 26.5, n = 1337) between 1970 and 1979, 124.0 (SD 23.3, n = 1240) between 1980 and 1989, and 111.0 (SD 19.0, n = 1110) between 1990 and 1999. The human population increased during this same period. Removal of belugas from the Beaufort Sea stock, including landed whales taken in the Alaskan harvests, is estimated at 189 per year. The sex ratio of landed belugas from the Mackenzie Estuary was 2.3 males:1 female. Median ages were 23.5 yr (47 growth layer groups [GLG]) for females (n = 80) and 24 yr (48 GLG) for males (n = 286). More than 92% of an aged sample (n = 368) from the harvest consisted of whales 10 or more years old (20 GLG). The rate of removal is small in relation to the expected maximum net productivity rate of this stock. -

June 15 2021 Notice the Registrar of Societies for the Northwest

June 15 2021 Notice The Registrar of Societies for the Northwest Territories intends to dissolve the societies listed below pursuant to section 27 of the Societies Act for failure to file, for a period of two consecutive years, financial statements and a list of the directors pursuant to section 18 of the Act. Any person connected with any of the societies listed below, who is aware that the society wishes to continue its operations, is requested to contact the Registrar immediately, and in any event, no later than 90 days following the date of this notice: Registrar of Societies, Department of Justice Government of the Northwest Territories P.O Box 1320, 5009-49th Street – SMH-1 Yellowknife NT X1A 2L9 Phone (867)767-9304, Fax (867)873-0243 Avis Le registraire des sociétés des Territoires du Nord-Ouest a l’intention de dissoudre les sociétés énumérées ci-dessous en vertu de l’article 27 de la Loi sur les sociétés, car elles n’ont pas déposé, pendant deux années consécutives, leurs états financiers et une liste des directeurs, conformément à l’article 18 de la Loi. Si une personne associée à l’une des sociétés énumérées ci-dessous sait que la société souhaite poursuivre ses activités, elle doit contacter le registraire immédiatement et, en tout état de cause, pas plus tard que 90 jours suivant la date de cet avis: Registraire des sociétés, ministère de la Justice Gouvernement des Territoires du Nord-Ouest 5009, 49ᵉ Rue, 1er étage, Édifice Stuart M. Hodgson C.P 1320, Yellowknife NT X1A 2L9 Tél.: (867)767-9304, Téléc.: (867) 873-0243 P.O. -

Inuvik Community Wellness Plan

INUVIK’S COMMUNITY WELLNESS PLAN 2018 Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC) April 2018 Table of Contents Background ................................................................................................................................................. 4 About Inuvik ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Wellness Planning Process ...................................................................................................................... 5 Education and Training ............................................................................................................................. 7 Higher Priority Goals .............................................................................................................................. 7 Projects or Programs to Address Goals ......................................................................................... 7 Medium Priority Goals ........................................................................................................................... 8 Projects or Programs to Address Goals ......................................................................................... 8 Lower Priority Goals ............................................................................................................................... 8 Projects or Programs to Address Goals ........................................................................................ -

The Characteristics of Some Permafrost Soils in The

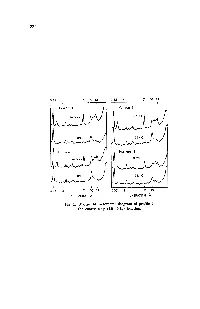

222 3.35 4 14 7 10 3.35 4 7 IO 14 I I, I 3.35 4 14 7 10 3.35 4 7 10 14 d-SPACING d-SPACING Fig. 1. X-ray dsractometer diagram of profile 2, the coarse clay (2.0 - 0.2~)fraction. Papers THE CHARACTERISTICS OF SOME PERMAFROST SOILS INTHE MACKENZIE VALLEY, N.W.T.* I J. H. Day and H. M. Rice* Introduction OILS in the tundra and subarctic regions of Canada were first described S in 1939 whenFeustel and others analyzed samples from northern Quebec, Keewatin and Franklin districts. More recently McMillan (1960), Beschel (1961) andLajoie (1954) describedsoils in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago and in northern Quebec. In the western part of the Northwest Territories only one profile (Leahey 1947) has been described under tundra vegetation, although other soils under forest, mostly unaffected by perma- frost,have been described (Leahey 1954, Dayand Leahey 1957, Wright et al. 1959). In Alaska, Tedrow and Hill (1955), Drew and Tedrow (1957), Tedrow et al. (1958),Douglas andTedrow (1960), Hill and Tedrow (1961) and Tedrow and Cantlon (1958) described several groups of soils, weathering processes, and concepts of soilformation and classification in thearctic environment. At least some of the kinds of soil they described in Alaska occur in Canada in a similar environment. This study was undertaken to investigate the characteristics of soils in a permafrost region under different typesof vegetation. The lower Mackenzie River valley is within the area of continuous permafrost (Brown 1960) and both tundra and boreal forest regions are readily accessible from the river. -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. “Creating a Framework for the Wisdom of the Community”: Review of Victim Services in Nunavut, Northwest and Yukon Territories “Creating a Framework for the Wisdom of the Community:” Review of Victim Services in Nunavut, Northwest and Yukon Territories RR03VIC-3e Mary Beth Levan Kalemi Consultants Policy Centre for Research and Victim issues Statistics Division September 2003 The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Justice Canada.