D8.2 - Policy Document About Technology Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Method for Constructing a New Extensible Nomenclature for Clinical Coding Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa

MEDINFO 2017: Precision Healthcare through Informatics 965 A.V. Gundlapalli et al. (Eds.) © 2017 International Medical Informatics Association (IMIA) and IOS Press. This article is published online with Open Access by IOS Press and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC 4.0). doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-830-3-965 A Method for Constructing a New Extensible Nomenclature for Clinical Coding Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa Sven Van Laere, Marc Nyssen, Frank Verbeke Department of Public Health (GEWE), Research Group of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics (BISI), Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Laarbeeklaan 103, 1090 Brussels, Belgium Abstract The word nomenclature has to be used with care in the context Clinical coding is a requirement to provide valuable data for of sub-Saharan Africa. By the word “nomenclature”, usually billing, epidemiology and health care resource allocation. In they understand: “a coding system to provide codes that are sub-Saharan Africa, we observe a growing awareness of the used in invoices, to specify the health services that were pro- need for coding of clinical data, not only in health insurances, vided for particular patients”. We define nomenclature in a but also in governments and the hospitals. Presently, coding broader way, also taking into account the clinical definition of systems in sub-Saharan Africa are often used for billing pur- health services. poses. In this paper we consider the use of a nomenclature to In this paper we will present a way to build this new nomen- also have a clinical impact. -

Description of Alternative Approaches to Measure and Place a Value on Hospital Products in Seven Oecd Countries

OECD Health Working Papers No. 56 Description of Alternative Approaches to Measure Luca Lorenzoni, and Place a Value Mark Pearson on Hospital Products in Seven OECD Countries https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kgdt91bpq24-en Unclassified DELSA/HEA/WD/HWP(2011)2 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 14-Apr-2011 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________ English text only DIRECTORATE FOR EMPLOYMENT, LABOUR AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS HEALTH COMMITTEE Unclassified DELSA/HEA/WD/HWP(2011)2 Health Working Papers OECD HEALTH WORKING PAPERS NO. 56 DESCRIPTION OF ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO MEASURE AND PLACE A VALUE ON HOSPITAL PRODUCTS IN SEVEN OECD COUNTRIES Luca Lorenzoni and Mark Pearson JEL Classification: H51, I12, and I19 English text only JT03300281 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DELSA/HEA/WD/HWP(2011)2 DIRECTORATE FOR EMPLOYMENT, LABOUR AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS www.oecd.org/els OECD HEALTH WORKING PAPERS http://www.oecd.org/els/health/workingpapers This series is designed to make available to a wider readership health studies prepared for use within the OECD. Authorship is usually collective, but principal writers are named. The papers are generally available only in their original language – English or French – with a summary in the other. Comment on the series is welcome, and should be sent to the Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, 2, rue André-Pascal, 75775 PARIS CEDEX 16, France. The opinions expressed and arguments employed here are the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the OECD. -

Health & Coding Terminological Systems

Health & Coding Terminological Systems Hamideh Sabbaghi, MS Ophthalmic Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran Definition of Code Code is considered as word, letter, or number which has been used as passwords instead of words or phrases. Coding System 1. Classification system 2. Nomenclature system Classification System A well-known system of corrections for naming different stages of the disease. Nomenclature System A medical list of a specific system of preferred terms for naming disease. WHO- FIC • Main/reference classification • Related classifications to the main/ reference classification • Driven classification from the main/ reference classification Main/reference classification • ICD- 10 (1990, WHA) • ICD- 11 (2007, WHO) • http://who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/ ICD with a commonest usage can be used for: • Identification of health trend, mortality and morbidity statistics. • Clinical and health research purposes. Main/reference classification • ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification) • ICF (International Classification of Function, Disability and Health) • ICHI (International Classification of Health Intervention) Related classifications to the main/ reference classification • ATC/DDD (The Anatomical Therapeutic chemical classification system with Defined Daily Doses) • ATCvet (The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System for veterinary medicinal products) • ICECI (International Classification of External Causes -

A Status Report, 2008-2009 WHO-FIC 2009/C006

Seoul, Republic of Korea WHO-FIC Education Committee: WHO-FIC 2009/C006 10 - 16 October 2009 A Status Report, 2008-2009 Cassia Maria Buchalla and Marjorie S. Greenberg Co-chairs Abstract The WHO-FIC Education Committee (EC) was established at the 2003 WHO-FIC Network meeting in Cologne, Germany, as a successor to the Subgroup on Training and Credentialing of the WHO-FIC Implementation Committee. New terms of reference were developed at the Cologne meeting to reflect generic tasks for education and training on the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Specific tasks have been agreed for both ICD and ICF. The Education Committee (EC) assists and advises WHO in improving the quality of use of the WHO classifications in member states through the development of training and certification strategies, the identification of best training practices and by providing a network for sharing expertise and experiences on education and training. The principal ICD tasks relate to an international training and certification program for ICD-10 mortality and morbidity coders; this program has been developed in conjunction with the International Federation of Health Records Organizations (IFHRO), a non-governmental organization in official relations with WHO. A Joint WHO-FIC – IFHRO Collaboration (JC) was established in late 2004 to carry forward this work. The Education Committee’s ICF tasks are being carried out in collaboration with the WHO-FIC Network’s Functioning and Disability Reference Group (FDRG). The Education Committee held four teleconferences in 2009 and a mid-year meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina, USA, in cooperation with the Joint Collaboration. -

Volume 3, Number 2, 2005

Volume 3, Number 2, 2005 Editorial Board Classification and terminology, what is in a name? Dr Marijke W. de Kleijn-de Vrankrijker Drs Huib Ten Napel The WHO-FIC Network meeting in October 2005 in Tokyo showed five Dr Willem M. Hirs projects on linking between WHO classifications and clinical terminologies: Realization and Design 1. R. Jakob, C. Çelik. Linkages between the ICD and terminologies A.C. Alta, Studio RIVM 2. K. Giannangelo & S. Fenton. Mapping: Creating the Terminology and Classification Published by Connection WHO-FIC Collaborating Centre in the 3. S. Zaiss, N. Hanser, N. Baerlecken. Comparison of ICHI and CCAM Basic Coding System Netherlands. 4. J.M. Rodrigues, A. Rector, P.E. Zanstra, R. Baud, J. Rogers, A.M. Rassinoux, S. Schultz, B. Responsibility for the information given Trombert, H. ten Napel, L. Clavel, E.J. vander Haring, C. Mateùs. Supporting WHO remains with the persons indicated. Classifications with GALEN tools Material from the Newsletter may be reproduced provided due 5. P.E. Zanstra, J..M. Rodrigues, A. Rector, M. Virtanen, G. Surjan, B. Üstün, P. Lewalle. acknowledgement is given. SemanticHealth. A semantic interoperability deployment and research roadmap; see p. 10 M. Virtanen chaired also a round table discussion with terminology experts, such Address WHO-FIC Collaborating Centre in the as C. Galinsky (Infoterm), J.M. Rodrigues (from the circle of Galen), K. Netherlands Spackman (from the circle of Snomed). Department for Public Health Forecasting In the summary report of the Network meeting it was stated that - "thanks to the National Institute of Public Health and the developments in informatics today - it is possible to link classifications and Environment (RIVM), P.O.Box 1, 3720 BA Bilthoven, The Netherlands. -

Ministry of Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia

WWW.MOH.GOV.GE Ministry of Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia Georgia Health Management Information System Strategy “Healthy Georgia, Connected to You” 2011 Table of Contents Executive Summary . 5 Goals and Objectives. 6 Governance. 7 Operational.Aspects. 9 HMIS Standards. .10 Message.Standards. .10 Vocabulary.Standards.for.Medical.Care. .11 Diagnosis.-.ICD.10,.Medcin. .12 Treatments.-.CPT. .13 Drugs.–RXNorm,.Multum,.Medispan,.First.Data.Bank. .13 Lab.–.LOINC,.SNOMED . .13 Administrative.Standards . .13 Citizens/Patients. .14 Provider.Credentialing,.Licensing.and.Unique.Identifiers. .14 National.Drug.Database . .14 Health.Data.Dictionary . .14 HMIS.Key.Indicators.and.Metrics. .15 HMIS.Core.Data.Sets. .15 HMIS Functionality . .16 Overview. .16 What.is.not.an.HMIS.component . .19 Software.Acquisition.versus.Development. .19 Selective.review.of.relevant.systems.that.are.already.available.in.Georgia . .23 Hesperus . .23 Vaccinations.system . .23 Electronic.registration.for.births.and.deaths.system. .23 TB.system,.AIDS.system,. .23 Surveillance.system.(DETRA).–.Infectious.Disease. .24 EU.project.for.MD’s.in.villages.to.be.equipped.with.400.PC’s . .24 SIMS. .24 Electronic Medical Record (EMR) . .25 Personal.and.Health.Information. .26 Results.Management. .26 Order.Management. .26 Decision.Support. .26 Reporting . .26 Electronic.Communication.and.Connectivity. .26 Patient.Support . .27 Administrative.Processes . .28 3 Financial Information System Functionality. .29 Georgian Health Data Repository (GHDR) . .32 Populating.the.Georgian.Health.Data.Repository.(GHDR) . .33 Extract,.Transform.Load. .34 Data.Domains.(Categories). .34 Data.Analysis.and.Presentation. .35 Reporting . .35 Dashboards . .36 GHDR.Uses. .36 Georgian.Healthcare.Statistics. .36 Monitoring.Healthcare.Costs. .36 Public.Health.Surveillance .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ...36 Decision.Support:..Improving.Patient.Care . -

November 5, 2003 – Letter to the Secretary – Comments on CHI

November 5, 2003 The Honorable Tommy G. Thompson Secretary Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Avenue SW Washington, D.C. 20201 Dear Secretary Thompson: The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) commends you for your commitment toward government wide adoption of clinical data standards that you first announced on March 21, 2003. NCVHS recognizes and appreciates that there is new momentum to adopt clinical data standards that is driven by you and the Consolidated Healthcare Informatics Initiative (CHI). Consequently, NCVHS is now working closely with CHI to study, select and recommend domain specific patient medical record information (PMRI) terminology standards. We have mutually developed a process that allows NCVHS to discuss in open, interactive sessions CHI recommendations as part of the CHI Council acceptance process. The NCVHS has the following comments on the attached set of CHI domain area recommendations: • The NCVHS concurs with the CHI recommendations for Interventions and Procedures: Part B, Laboratory Test Order Names. • The NCVHS concurs with the CHI recommendations for the Medication Domain as modified in the attached document. We further note: o the need for additional funding for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to expedite the publication of a publicly available version of their Unique Ingredient Identifier (UNII) codes and to provide continued funding to maintain the UNII code standard; o that the dosage and administration sub-domain be investigated in the next phase of the CHI process; and o that the FDA National Drug Code (NDC) process be investigated and improvements identified be expeditiously pursued. • The NCVHS concurs with the CHI recommendations for the Immunization Domain as modified in the attached document. -

Ata Lements for Mergency Epartment Ystems

D ata E lements for E mergency D epartment S ystems Release 1.0 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES CDCCENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION D ata E lements for E mergency D epartment S ystems Release 1.0 National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Atlanta, Georgia 1997 Data Elements for Emergency Department Systems, Release 1.0 (DEEDS) is the result of contributions by participants in the National Workshop on Emergency Department Data, held January 23-25, 1996, in Atlanta, Georgia, subsequent review and comment by individuals who read Release 1.0 in draft form, and finalization by a multidisciplinary writing committee. DEEDS is a set of recommendations published by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention David Satcher, MD, PhD, Director National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Mark L. Rosenberg, MD, MPP, Director Division of Acute Care, Rehabilitation Research, and Disability Prevention Richard J. Waxweiler, PhD, Director Acute Care Team Daniel A. Pollock, MD, Leader Production services were provided by the staff of the Office of Communication Resources, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, and the Management Analysis and Services Office: Editing Valerie R. Johnson Cover Design and Layout Barbara B. Lord Use of trade names is for identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This document and subsequent revisions can be found at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Web site: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/deedspage.htm Suggested Citation: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. -

(USCDI), Version 1, July 2020 Errata

Allergies and Intolerances .... 5 The USCDI is a standardized Assessment and Plan of set of health data classes and Treatment ............................ 5 Care Team Member(s) ......... 6 constituent data elements for Clinical Notes ........................ 7 nationwide, interoperable Goals ..................................... 8 Health Concerns ................... 8 health information exchange. Immunizations ...................... 9 Laboratory ............................ 9 A USCDI “Data Class” is an aggregation of various Data Elements by a common theme or use case. Medications ........................ 10 Patient Demographics ........ 10 A USCDI “Data Element” is the most granular level Problems ............................ 12 at which a piece of data is represented in the USCDI Procedures ......................... 12 for exchange. Provenance ........................ 13 Smoking Status ................... 13 Unique Device Identifier(s) for a Patient’s Implantable Device(s) ............................. 13 Vital Signs ........................... 14 2 Version History Version # Description of change Version Date 1 First Publication February 2020 1 (July 2020 Corrections to Applicable Standards July 2020 Errata) • Substance (Medication) - Removed UCUM • Patient’s Goals, Health Concerns, Assessment and Plan of Treatment - Removed LOINC, SNOMED CT • Laboratory Tests, Values/Results - Removed SNOMED CT and UCUM • Medications - Removed UCUM 3 USCDI v1 Summary of Data Classes and Data Elements Allergies and Intolerances Laboratory Smoking Status -

Report-Health Terminologies and Vocabularies Environmental Scan

Health Terminologies and Vocabularies Environmental Scan Conducted for the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics Subcommittee on Standards September 14, 2018 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Health Terminologies and Vocabularies Environmental Scan NCVHS Subcommittee on Standards This report was written by Susan L. Roy, MS, MLS, SNOMED CT Coordinator, and Vivian A. Auld, MLIS, Senior Specialist for Health Data Standards, both with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Library of Medicine, in collaboration with the NCVHS Standards Subcommittee: NCVHS Membership William W. Stead, MD, NCVHS Chair Nicholas L. Coussoule,* Subcommittee Co-chair Alexandra Goss,* Subcommittee Co-chair Bruce B. Cohen, PhD David A. Ross, ScD Debra Strickland, MS* Denise E. Love, BSN, MBA* Jacki Monson, JD Linda L. Kloss, MA, RHIA*, Terminology and Vocabulary Project Lead Llewellyn J. Cornelius, PhD Richard W. Landen, MPH, MBA* Robert L. Phillips, Jr., MD, MSPH Roland J. Thorpe, Jr., PhD Vickie M. Mays, PhD, MSPH *Member of the Subcommittee on Standards Rebecca Hines, MHS, NCVHS Executive Secretary/DFO Health Scientist National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, HHS Rashida Dorsey, PhD, MPH, NCVHS Executive Staff Director Director, Division of Data Policy Senior Advisor on Minority Health and Health Disparities Office of Science and Data Policy Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) serves as the advisory committee to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) on health data, statistics, privacy, national health information policy, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (42U.S.C.242k[k]). -

(Child Core Set) Technical Specifications and Reso

Core Set of Children's Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid and CHIP (Child Core Set) Technical Specifications and Resource Manual for Federal Fiscal Year 2019 Reporting February 2019 Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services This page left blank for double-sided copying ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For Proprietary Codes: CPT® codes copyright 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a trademark of the American Medical Association. No fee schedules, basic units, relative values or related listings are included in CPT. The AMA assumes no liability for the data contained herein. Applicable FARS/DFARS restrictions apply to government use. SNOMED CLINICAL TERMS (SNOMED CT®) copyright 2004-2018 The International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. All Rights Reserved. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-9-CM is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-9-PCS) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-9-PCS is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-10-CM is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-10-PCS is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. This material contains content from LOINC® (http://loinc.org). -

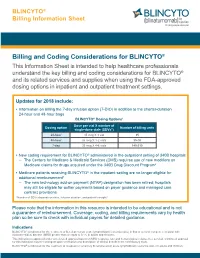

Billing and Coding Considerations for BLINCYTO®

BLINCYTO® Billing Information Sheet Billing and Coding Considerations for BLINCYTO® This Information Sheet is intended to help healthcare professionals understand the key billing and coding considerations for BLINCYTO® and its related services and supplies when using the FDA-approved dosing options in inpatient and outpatient treatment settings. Updates for 2018 include: • Information on billing the 7-day infusion option (7-DIO) in addition to the shorter-duration 24-hour and 48-hour bags BLINCYTO® Dosing Options1 Dose per vial X number of Dosing option Number of billing units single-dose vials (SDVs*) 24-hour 35 mcg X 1 vial 35 48-hour 35 mcg X 1-2 vials 35-70 7-day 35 mcg X 4-6 vials 140-210 • New coding requirement for BLINCYTO® administered in the outpatient setting of 340B hospitals – The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires use of new modifiers on Medicare claims for drugs acquired under the 340B Drug Discount Program2 • Medicare patients receiving BLINCYTO® in the inpatient setting are no longer eligible for additional reimbursement3 – The new technology add-on payment (NTAP) designation has been retired; hospitals may still be eligible for outlier payments based on payer guidance and managed care contract provisions *Number of SDVs depends on dose, infusion duration, and patient's weight.1 Please note that the information in this resource is intended to be educational and is not a guarantee of reimbursement. Coverage, coding, and billing requirements vary by health plan so be sure to check with individual payers for detailed guidance. Indications BLINCYTO® is indicated for the treatment of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in first or second complete remission with minimal residual disease (MRD) greater than or equal to 0.1% in adults and children.