Report-Health Terminologies and Vocabularies Environmental Scan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Systematic Review of Omaha System Literature in Turkey

Nursing Informatics 2016 633 W. Sermeus et al. (Eds.) © 2016 IMIA and IOS Press. This article is published online with Open Access by IOS Press and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-658-3-633 A Systematic Review of Omaha System Literature in Turkey Selda SECGİNLİ, PhD, Associate Professor a,1, Nursen O. NAHCİVAN, PhD, Professora, Karen A. MONSEN PhD, RN, FAAN b a Florence Nightingale Nursing Faculty, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey b School of Nursing, University of Minnesota and Institute for Health Informatics, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA Keywords. Omaha System; Systematic review; Standardized terminology; Turkey 1. Introduction The Omaha System is a comprehensive tool for enhancing practice, documentation and information management across health care settings.1 This systematic review presents the state of science on the use of the Omaha System in practice, research, and education Turkey and to suggest areas for future research. 2. Methods A systematic review of the literature published between 2000 and 2014 was conducted, searching electronic databases of Ovid MEDLINE, PUB MED, Cochrane CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Knowledge, Scopus, Google Scholar, ULAKBIM Turkish Medical Database and Council of Higher Education Thesis Center. The primary key word “Omaha System” and its Turkish translations were used for searching. Methodological quality of the reviewed research studies was evaluated with Joanna Briggs Institute MAStARI Critical Appraisal checklists for identifying methodological flaws in the studies included. Articles were included if studies were conducted in Turkey and published in either Turkish or English. All articles were read and then categorized to one of five categories: “analyzing client problems”, “clinical process”, “client outcomes”, “advanced classification research”, and “reports on unpublished master’s and doctoral dissertations”. -

The Benefits of Using Standardized Nursing Terminology

Page 1 of 20 Selecting a Standardized Terminology for the Electronic Health Record that Reveals the Impact of Nursing on Patient Care By Cynthia B. Lundberg, R.N., BSN; SNOMED Terminology Solutions; Judith J. Warren, PhD, RN, BC, FAAN, FACMI; University of Kansas; Jane Brokel, PhD, RN, NANDA International; Gloria M. Bulechek, PhD, RN, FAAN; Nursing Interventions Classification; Howard K. Butcher, PhD, RN, APRN, BC; Nursing Interventions Classification; Joanne McCloskey Dochterman, PhD, RN, FAAN; Nursing Interventions Classification; Marion Johnson, PhD, RN; Nursing Outcomes Classification; Meridean Maas PhD, RN; Nursing Outcomes Classification; Karen S. Martin, RN, NSN, FAAN; Omaha System; Sue Moorhead PhD, RN, Nursing Outcomes Classification; Christine Spisla, RN, MSN; SNOMED Terminology Solutions; Elizabeth Swanson, PhD, RN; Nursing Outcomes Classification, Sharon Giarrizzo-Wilson, RN, BSN/MS, CNOR, Association of PeriOperative Registered Nurses Citation: Lundberg, C., Warren, J.., Brokel, J., Bulechek, G., Butcher, H., McCloskey Dochterman, J., Johnson, M., Mass, M., Martin, K., Moorhead, S., Spisla, C., Swanson, E., & Giarrizzo-Wilson, S. (June, 2008). Selecting a Standardized Terminology for the Electronic Health Record that Reveals the Impact of Nursing on Patient Care. Online Journal of Nursing Informatics (OJNI), 12, (2). Available at http:ojni.org/12_2/lundberg.pdf Page 2 of 20 Abstract Using standardized terminology within electronic health records is critical for nurses to communicate their impact on patient care to the multidisciplinary team. The universal requirement for quality patient care, internal control, efficiency and cost containment, has made it imperative to express nursing knowledge in a meaningful way that can be shared across disciplines and care settings. The documentation of nursing care, using an electronic health record, demonstrates the impact of nursing care on patient care and validates the significance of nursing practice. -

November 5, 2003 – Letter to the Secretary – Comments on CHI

November 5, 2003 The Honorable Tommy G. Thompson Secretary Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Avenue SW Washington, D.C. 20201 Dear Secretary Thompson: The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) commends you for your commitment toward government wide adoption of clinical data standards that you first announced on March 21, 2003. NCVHS recognizes and appreciates that there is new momentum to adopt clinical data standards that is driven by you and the Consolidated Healthcare Informatics Initiative (CHI). Consequently, NCVHS is now working closely with CHI to study, select and recommend domain specific patient medical record information (PMRI) terminology standards. We have mutually developed a process that allows NCVHS to discuss in open, interactive sessions CHI recommendations as part of the CHI Council acceptance process. The NCVHS has the following comments on the attached set of CHI domain area recommendations: • The NCVHS concurs with the CHI recommendations for Interventions and Procedures: Part B, Laboratory Test Order Names. • The NCVHS concurs with the CHI recommendations for the Medication Domain as modified in the attached document. We further note: o the need for additional funding for the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to expedite the publication of a publicly available version of their Unique Ingredient Identifier (UNII) codes and to provide continued funding to maintain the UNII code standard; o that the dosage and administration sub-domain be investigated in the next phase of the CHI process; and o that the FDA National Drug Code (NDC) process be investigated and improvements identified be expeditiously pursued. • The NCVHS concurs with the CHI recommendations for the Immunization Domain as modified in the attached document. -

Ata Lements for Mergency Epartment Ystems

D ata E lements for E mergency D epartment S ystems Release 1.0 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES CDCCENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION D ata E lements for E mergency D epartment S ystems Release 1.0 National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Atlanta, Georgia 1997 Data Elements for Emergency Department Systems, Release 1.0 (DEEDS) is the result of contributions by participants in the National Workshop on Emergency Department Data, held January 23-25, 1996, in Atlanta, Georgia, subsequent review and comment by individuals who read Release 1.0 in draft form, and finalization by a multidisciplinary writing committee. DEEDS is a set of recommendations published by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention David Satcher, MD, PhD, Director National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Mark L. Rosenberg, MD, MPP, Director Division of Acute Care, Rehabilitation Research, and Disability Prevention Richard J. Waxweiler, PhD, Director Acute Care Team Daniel A. Pollock, MD, Leader Production services were provided by the staff of the Office of Communication Resources, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, and the Management Analysis and Services Office: Editing Valerie R. Johnson Cover Design and Layout Barbara B. Lord Use of trade names is for identification only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This document and subsequent revisions can be found at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Web site: http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/deedspage.htm Suggested Citation: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. -

Standard Nursing Terminologies: a Landscape Analysis

Standard Nursing Terminologies: A Landscape Analysis MBL Technologies, Clinovations, Contract # GS35F0475X Task Order # HHSP2332015004726 May 15, 2017 Table of Contents I. Introduction ....................................................................................................... 4 II. Background ........................................................................................................ 4 III. Landscape Analysis Approach ............................................................................. 6 IV. Summary of Background Data ............................................................................ 7 V. Findings.............................................................................................................. 8 A. Reference Terminologies .....................................................................................................8 1. SNOMED CT ................................................................................................................................... 8 2. Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) ........................................................ 10 B. Interface Terminologies .................................................................................................... 11 1. Clinical Care Classification (CCC) System .................................................................................... 11 2. International Classification for Nursing Practice (ICNP) ............................................................. 12 3. NANDA International -

(USCDI), Version 1, July 2020 Errata

Allergies and Intolerances .... 5 The USCDI is a standardized Assessment and Plan of set of health data classes and Treatment ............................ 5 Care Team Member(s) ......... 6 constituent data elements for Clinical Notes ........................ 7 nationwide, interoperable Goals ..................................... 8 Health Concerns ................... 8 health information exchange. Immunizations ...................... 9 Laboratory ............................ 9 A USCDI “Data Class” is an aggregation of various Data Elements by a common theme or use case. Medications ........................ 10 Patient Demographics ........ 10 A USCDI “Data Element” is the most granular level Problems ............................ 12 at which a piece of data is represented in the USCDI Procedures ......................... 12 for exchange. Provenance ........................ 13 Smoking Status ................... 13 Unique Device Identifier(s) for a Patient’s Implantable Device(s) ............................. 13 Vital Signs ........................... 14 2 Version History Version # Description of change Version Date 1 First Publication February 2020 1 (July 2020 Corrections to Applicable Standards July 2020 Errata) • Substance (Medication) - Removed UCUM • Patient’s Goals, Health Concerns, Assessment and Plan of Treatment - Removed LOINC, SNOMED CT • Laboratory Tests, Values/Results - Removed SNOMED CT and UCUM • Medications - Removed UCUM 3 USCDI v1 Summary of Data Classes and Data Elements Allergies and Intolerances Laboratory Smoking Status -

Cross-Mapping the ICNP with NANDA, HHCC, Omaha System and NIC for Unified Nursing Language System Development

Original article Cross-mapping the ICNP with NANDA, HHCC, Omaha System and NIC for unified nursing language system development S. Hyun MSN, RN & H. A. Park PhD, RN 1 Researcher, College of Nursing Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea 2 Associate Professor, College of Nursing Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea Keywords Abstract Cross-mapping, ICNP, Nursing language plays an important role in describing and defining nursing Nursing Languages, Unified Nursing phenomena and nursing actions. There are numerous vocabularies describing Language System nursing diagnoses, interventions and outcomes in nursing. However, the lack of a standardized unified nursing language is considered a problem for further development of the discipline of nursing. In an effort to unify the nursing languages, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) has proposed the International Classification for Nursing Practice (ICNP) as a unified nursing language system. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the inclusiveness and expressiveness of the ICNP terms by cross-mapping them with the existing nursing terminologies, specifically the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) taxonomy I, the Omaha System, the Home Health Care Classification (HHCC) and the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC). Nine hundred and seventy-four terms from these four classifications were cross-mapped with the ICNP terms. This was performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Composing a Nursing Diagnosis and Guidelines for Composing a Nursing Intervention, which were suggested by the ICNP development team. An expert group verified the results. The ICNP Phenomena Classification described 87.5% of the NANDA diagnoses, 89.7% of the HHCC diagnoses and 72.7% of the Omaha System problem classification scheme. -

(Child Core Set) Technical Specifications and Reso

Core Set of Children's Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid and CHIP (Child Core Set) Technical Specifications and Resource Manual for Federal Fiscal Year 2019 Reporting February 2019 Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services This page left blank for double-sided copying ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For Proprietary Codes: CPT® codes copyright 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. CPT is a trademark of the American Medical Association. No fee schedules, basic units, relative values or related listings are included in CPT. The AMA assumes no liability for the data contained herein. Applicable FARS/DFARS restrictions apply to government use. SNOMED CLINICAL TERMS (SNOMED CT®) copyright 2004-2018 The International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. All Rights Reserved. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-9-CM is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-9-PCS) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-9-PCS is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-10-CM is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) is published by the World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-10-PCS is an official Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act standard. This material contains content from LOINC® (http://loinc.org). -

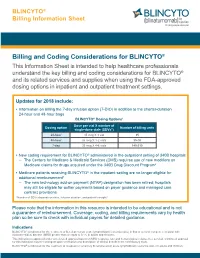

Billing and Coding Considerations for BLINCYTO®

BLINCYTO® Billing Information Sheet Billing and Coding Considerations for BLINCYTO® This Information Sheet is intended to help healthcare professionals understand the key billing and coding considerations for BLINCYTO® and its related services and supplies when using the FDA-approved dosing options in inpatient and outpatient treatment settings. Updates for 2018 include: • Information on billing the 7-day infusion option (7-DIO) in addition to the shorter-duration 24-hour and 48-hour bags BLINCYTO® Dosing Options1 Dose per vial X number of Dosing option Number of billing units single-dose vials (SDVs*) 24-hour 35 mcg X 1 vial 35 48-hour 35 mcg X 1-2 vials 35-70 7-day 35 mcg X 4-6 vials 140-210 • New coding requirement for BLINCYTO® administered in the outpatient setting of 340B hospitals – The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) requires use of new modifiers on Medicare claims for drugs acquired under the 340B Drug Discount Program2 • Medicare patients receiving BLINCYTO® in the inpatient setting are no longer eligible for additional reimbursement3 – The new technology add-on payment (NTAP) designation has been retired; hospitals may still be eligible for outlier payments based on payer guidance and managed care contract provisions *Number of SDVs depends on dose, infusion duration, and patient's weight.1 Please note that the information in this resource is intended to be educational and is not a guarantee of reimbursement. Coverage, coding, and billing requirements vary by health plan so be sure to check with individual payers for detailed guidance. Indications BLINCYTO® is indicated for the treatment of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in first or second complete remission with minimal residual disease (MRD) greater than or equal to 0.1% in adults and children. -

1 Application of the Omaha System for Persons with Psychiatric/Mental

1 Application of the Omaha System for Persons with Psychiatric/Mental Health Problems. Phyllis M. Connolly PhD, PMHCNS-BC (revised June 09). Purpose: This module provides an opportunity for you to successfully apply the Omaha System for persons who may be experiencing psychiatric/mental health problems. In addition, you will have an increased awareness of the use of the Omaha System with the School of Nursing Nurse Managed Centers. Learning Outcomes: After completing this module you will be able to: • Identify appropriate Omaha System problems during an assessment of a person with psychiatric/mental health problems. • Select the appropriate interventions and targets for the identified problems. • Correctly rate the outcomes of the problem in the areas of Knowledge (K), Behavior (B), and Status (S). • Develop a care plan for future care. • Discuss the use of the Omaha data collection within the Nurse Managed Centers. • Recognize the relationship between the use of the Omaha System and providing quality care. • Identify the protocol for data collection of the Omaha in the Nurse Managed Centers. • Document services provided on a Standardized Omaha System Documentation tool. • Collect pre and post Omaha Data on top 3 priority problems for assigned clients on a scantron form. • Discuss the value of the Omaha System for providing collaborative care. Required learning activities: 1. Purchase a copy of the Omaha Module in the Associated Students Print shop and complete the module. 2. Read the case study for a person in the community with psychiatric symptoms. 3. Based on the case study provided identify the two top priority problems, include the Domain. -

The Role of Family Practice in Different Health Care Systems

January 2002 · Vol. 51, No. 1 JFP ONLINE The Role of Family Practice in Different Health Care Systems A Comparison of Reasons for Encounter, Diagnoses, and Interventions in Primary Care Populations in the Netherlands, Japan, Poland, and the United States I.M. Okkes, MA, PhD; G.O. Polderman, MD; G.E. Fryer, PhD; T. Yamada, MD; M. Bujak, MD; S.K. Oskam, MSc, PhD; L.A. Green, MD; H. Lamberts, MD, PhD Amsterdam and Amstelveen, the Netherlands; Tokyo, Japan; Katowice, Poland; and Washington, DC Submitted, revised, October 21, 2001. From the Academic Medical Center/University of Amsterdam, Division of Public Health, Department of Family Practice, Amsterdam (I.M.O., S.K.O., H.L.); Family Physician, Transition Project, Amstelveen (G.O.P.); the Robert Graham Center: Policy Studies in Family Practice and Primary Care, Washington, DC (G.E.F., L.A.G.); the Japanese Association for Development of Community Medicine, Tokyo (T.Y.); and the Silesian Medical School, Katowice (M.B.). Reprint requests should be addressed to I.M. Okkes, MA, PhD, Academic Medical Center/University of Amsterdam, Division Public Health, Department of Family Practice, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, the Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected]. z OBJECTIVE: Our goal was to compare the content of family practice in different countries using databases containing information on reasons for encounter, diagnoses, and interventions that are coded with or can be addressed by the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC). z STUDY DESIGN: In the Netherlands, Japan, and Poland data were collected identically with an electronic patient record (Transhis). -

2018 Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes

2018 ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE REPORT OF DRUG-RELATED RISKS AND OUTCOMES UNITED STATES Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes | United States CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control | 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Surveillance Report was prepared by staff from the National Disclaimer Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC), Centers for Disease The findings and conclusions in Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human this report are those of the authors Services, Atlanta, Georgia. and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This Contributors to this report included: Brooke E. Hoots, PhD, MSPH1, 2 3 research was supported in part by Likang Xu, MD, MS , Mbabazi Kariisa, PhD , Nana Otoo Wilson, PhD, an appointment to the Research 1 1 1,4 MPH, MSc , Rose A. Rudd, MSPH , Lawrence Scholl, PhD, MPH , Lyna Participation Program at the Centers 1 1 Schieber, MD, DPhil , and Puja Seth, PhD for Disease Control and Prevention 1Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention (DUIP), National Center for administered by the Oak Ridge Injury Prevention and Control, CDC Institute for Science and Education 2Division of Analysis, Research, and Practice Integration (DARPI), through an interagency agreement National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC between the U.S. Department of 3Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, TN Energy and CDC. 4Epidemic Intelligence Service, CDC All material in this report is in the public domain and may be used Corresponding authors: Brooke E.