Report on State Definitions, Jurisdiction and Mitigation Requirements in State Programs for Ephemeral, Intermittent and Perennial Streams in the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riparian Buffer

Riparian Buffer A Technical Primer on Assessing Potential Water Quality Improvements for the Quantifying Benefits of Miyun Reservoir in Beijing, China Watershed Interventions September 2016 Prepared by: “Andrew” Feng Fang, Ph.D. Work supported by: Mark S. Kieser 536 E. Michigan Ave, Suite 300 Kalamazoo, MI 49007 USA The China Mega-City Water Fund (CMWF) was launched in August of 2015 in cooperation with the Beijing Forestry Society (BFS), China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation (CBCGDF), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and Forest Trends. Once fully operating, the CMWF will identify, fund, and help implement watershed improvement projects (“interventions”) to benefit water quality and water quantity in the Miyun Reservoir. The City of Beijing relies in part on this reservoir as a critical drinking water supply. A notable challenge facing the CMWF, and other water funds throughout the world, is the ability to reasonably estimate water quality and/or water quantity benefits associated with specific interventions. Recent 2016 efforts have established an operating framework for the CMWF that will evaluate various watershed interventions in the context of relatively simple, established performance metrics for water quality and water quantity benefits. Coupled with projected costs for such interventions, the CMWF will be able to assess, compare and optimize benefits associated with its investments in watershed improvements with this framework. This Technical Primer1 represents an initial examination of quantification methods that the CMWF and others may use to reliably estimate water resource benefits derived from particular land management interventions in the watershed of the Miyun Reservoir. This approach relies upon existing studies from both the Miyun Reservoir watershed and other basins in China. -

James City County Perennial Stream Protocol Guidance Manual

James City County Perennial Stream Protocol Guidance Manual Purpose This protocol defines the procedure for making field determinations of the presence and the origin of a perennial stream. The procedure was developed to meet the requirement of James City County’s Chesapeake Bay Preservation Ordinance, Section 23-8, to perform site-specific field evaluations to determine the boundaries of Resource Protection Areas (RPA) and Section 23-10(2) to identify water bodies with perennial flow. Development of the protocol was finalized using funds from the Chesapeake Bay Implementation Grant #BAY-2007-14-PT awarded to the County by the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR). Introduction This protocol describes the process of determining whether a stream in James City County has perennial flow, and if necessary, determining the origin of the perennial stream. The origin of the perennial reach may occur as a transition from an ephemeral or intermittent reach or may occur at a spring with no upslope stream channel. The field identification of a perennial stream is based on the combination of hydrological, physical and biological characteristics of a stream. In the protocol, the field indicators of these characteristics are classified as primary or secondary and ranked using a weighted, four-tiered scoring system similar to the current system developed by the North Carolina Division of Water Quality (NCDWQ 2005) as modified to address conditions in James City County. A stream reach is classified as perennial based on the overall score but with consideration of other supporting information such as long term monitoring or historic information in certain situations. -

Creek, Stream, Or Branch

Creek, Stream, or Branch What is the difference between a creek, stream or a branch, and when does a spring become one of them? Let me introduce you to the world of stream classification. To begin at the beginning, streams have their origin high up in their watershed. A watershed is that area in which precipitation falls and collects into water bodies. On a large scale, Mitchell, Yancey, and Avery Counties drain into the French Broad River Basin. Within these river basins are many sub-basins or smaller watersheds that drain into tributaries or creeks. When rainfall hits the earth it either infiltrates and recharges groundwater or it runs off and goes into a stream. Most infiltrating rainfall enters shallow groundwater which feeds year-round streams, which is why year-round, or perennial streams and rivers run with water even in dry weather. Old hand dug or bored (shallow) wells tap into shallow ground water, which is why shallow wells can dry- up during prolonged droughts. Of the approximately 40-55 inches of annual rainfall that Mitchell, Yancey, and Avery Counties receive in an average year, only one inch penetrates into the deep groundwater on which most drilled wells depend. If a stream runs wet only during rainfall events, it is called an ephemeral stream. Ephemeral steams depend upon stormwater runoff for water. These streams are perched above the shallow water table, so when rain stops falling, they dry up. The second level of stream is called an intermittent stream. Intermittent streams run with water only during part of the year, typically during winter and spring when shallow water tables are highest. -

A Hydrological Framework for Persistent River Pools in Semi- Arid Environments

https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-2020-133 Preprint. Discussion started: 1 April 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. A hydrological framework for persistent river pools in semi- arid environments 1 Sarah A. Bourke , Margaret Shanafield2, Paul Hedley3, Shawan Dogramaci3 5 1School of Earth Sciences, University of Western Australia, Crawley WA 6009 Australia 2College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, Bedford Park, SA 5042, Australia 3Rio Tinto Iron Ore, Perth, WA 6000 Australia Correspondence to: Sarah A. Bourke ([email protected]) Abstract 10 Persistent surface water pools along non-perennial rivers represent an important water resource for the plants, animals, and humans that inhabit semi-arid regions. While ecological studies of these features are not uncommon, these are rarely accompanied by a rigorous examination of the hydrological and hydrogeological characteristics that create or support the pools. Here we present an overarching framework for understanding the hydrology of persistent pools based on data from 22 pools in the Hamersley Basin in Western Australia. Three dominant 15 mechanisms that control the occurrence of persistent pools have been identified; perched pools, through flow pools and groundwater discharge pools. Groundwater discharge pools are further categorized into those that are present because of a geological contact or barrier, and those that are controlled by topography. A suite of diagnostic tools (including geological mapping, hydraulic data and hydrochemical surveys) is generally required to identify the mechanism supporting persistent pools. Perched pools are sensitive to climate variability but their 20 persistence is largely independent of groundwater withdrawals. Water fluxes to pools from alluvial and bedrock aquifers can vary seasonally and resolving these inputs is generally non-trivial. -

Protecting Headwaters: the SCIENTIFIC BASIS for SAFEGUARDING STREAM and RIVER ECOSYSTEMS

Protecting Headwaters: THE SCIENTIFIC BASIS FOR SAFEGUARDING STREAM AND RIVER ECOSYSTEMS A Research Synthesis from the Stroud™ Water Research Center Small headwater streams like this one are the lifeblood of our streams and rivers. Protecting these headwaters is essential to preserving a healthy freshwater ecosystem and protecting our freshwater resources. About THE STROUD WATER RESEARCH CENTER The Stroud Water Research Center seeks to advance knowledge and stewardship of fresh water through research, education and global outreach and to help businesses, landowners, policy makers and individuals make informed decisions that affect water quality and availability around the world. The Stroud Water Research Center is an independent, 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization. For more information go to www.stroudcenter.org. Sierra Club provided partial support for writing this white paper. Editing and executive summary by Matt Freeman. Contributors STROUD WATER RESEARCH CENTER SCIENTISTS AUTHORED PROTECTING HEADWATERS Louis A. Kaplan Senior Research Scientist Thomas L. Bott Vice President Senior Research Scientist John K. Jackson Senior Research Scientist J. Denis Newbold Research Scientist Bernard W. Sweeney Director President Senior Research Scientist For a downloadable, printer-ready copy of this document go to: http://www.stroudcenter.org/research/PDF/ProtectingHeadwaters.pdf. For a downloadable, printer-ready copy of the Executive Summary only, go to: http://www.stroudcenter.org/research/PDF/ProtectingHeadwaters_ExecSummary.pdf. 1 STROUD WATER RESEARCH CENTER | PROTECTING HEADWATERS Small headwater streams like this one are the lifeblood of our streams and rivers. Protecting these headwaters is essential to preserving a healthy freshwater ecosystem and protecting our freshwater resources. Executive Summary HEALTHY HEADWATERS ARE ESSENTIAL TO PRESERVE OUR FRESHWATER RESOURCES Scientific evidence clearly shows that healthy headwaters — tributary streams, intermittent streams, and spring seeps — are essential to the health of stream and river ecosystems. -

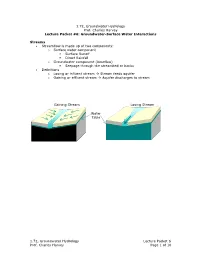

1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Prof. Charles Harvey Lecture Packet #6: Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions

1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Prof. Charles Harvey Lecture Packet #6: Groundwater-Surface Water Interactions Streams • Streamflow is made up of two components: o Surface water component Surface Runoff Direct Rainfall o Groundwater component (baseflow) Seepage through the streambed or banks • Definitions o Losing or influent stream Æ Stream feeds aquifer o Gaining or effluent stream Æ Aquifer discharges to stream Gaining Stream Losing Stream Water Table 1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Lecture Packet 6 Prof. Charles Harvey Page 1 of 10 Stream-Aquifer Interactions Base Flow – Contribution to streamflow from groundwater • Upper reaches provide subsurface contribution to streamflow (flood wave). • Lower reaches provide bank storage which can moderate a flood wave. Flood hydrograph with no bank storage Water leaving bank storage Flood hydrograph with bank storage 0 Stream Discharge 0 Water entering bank storage t0 tP Recharge Recharge Discharge Groundwater inflow and bank storage Groundwater inflow alone Volume Bank Storage Storage Bank 0 Stream Discharge 0 t0 tP t0 tP Springs • A spring (or seep) is an area of natural discharge. • Springs occur where the water table is very near or meets land surface. o Where the water table does not actually reach land surface, capillary forces may still bring water to the surface. • Discharge may be permanent or ephemeral • The amount of discharge is related to height of the water table, which is affected by o Seasonal changes in recharge o Single storm events Types of Springs • Depression spring Land surface dips to intersect the water table • Contact spring Water flows to the surface where a low permeability bed • Fault spring impedes flow • Sinkhole spring Similar to a depression spring, but flow is limited to • Joint spring fracture zones, joints, or dissolution channels • Fracture spring 1.72, Groundwater Hydrology Lecture Packet 6 Prof. -

Virginia Soil and Water Conservation Board Guidance Document on the Methodology for Identifying Perennial Streams

VIRGINIA SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION BOARD GUIDANCE DOCUMENT ON THE METHODOLOGY FOR IDENTIFYING PERENNIAL STREAMS (Approved December XX, 2020) Summary: This guidance document provides guidance to agricultural producers on the methodology the Board and the Department will utilize to identify perennial streams for the purpose of ensuring compliance with §62.1-44.123 of the Code of Virginia. Electronic Copy: An electronic copy of this guidance in PDF format is available on the Regulatory TownHall under the Virginia Soil and Water Conservation Board at http://townhall.virginia.gov/L/GDocs.cfm. Contact Information: Please contact the Department of Conservation and Recreation’s Division of Soil and Water Conservation by calling 804.225.3653 with any questions regarding the application of this guidance. Disclaimer: This document is provided as guidance and, as such, sets forth standard operating procedures for the Department of Conservation and Recreation in administering the responsibilities established in §62.1-44.123 on behalf of the Virginia Soil and Water Conservation Board (Board). This guidance provides a general interpretation of the applicable Code and Regulations but is not meant to be exhaustive in nature. Each situation may differ and may require additional interpretation. This is not intended to and cannot be relied on to create any rights, substantive or procedural, on the part of any person or entity. Methodology to Identify Perennial Streams I. Authority: The Code of Virginia, §62.1-44.123, states: “Any person who owns property in the Chesapeake Bay watershed on which 20 or more bovines are pastured shall install and maintain stream exclusion practices sufficient to exclude all such bovines from any perennial stream in the watershed.” 1 The fifth enactment clause in both Chapters 1185 and 1186 of the 2020 Acts of Assembly requires the Board to adopt a methodology to be used for identifying perennial streams no later than December 31, 2020. -

Guidance for Stream Restoration

United States Department of Agriculture Guidance for Stream Restoration Steven E. Yochum Forest National Stream & Technical Note Service Aquatic Ecology Center TN-102.4 May 2018 Yochum, Steven E. 2018. Guidance for Stream Restoration. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, National Stream & Aquatic Ecology Center, Technical Note TN-102.4. Fort Collins, CO. Cover Photos: Top-right: Illinois River, North Park, Colorado. Photo by Steven Yochum Bottom-left: Whychus Creek, Oregon. Photo by Paul Powers ABSTRACT A great deal of effort has been devoted to developing guidance for stream restoration. The available resources are diverse, reflecting the wide ranging approaches used and expertise required to develop effective stream restoration projects. To help practitioners sort through the extensive information, this technical note has been developed to provide a guide to the available guidance. The document structure is primarily a series of short literature reviews followed by a hyperlinked reference list for readers to find more information on each topic. The primary topics incorporated into this guidance include general methods, an overview of stream processes and restoration, case studies, data compilation, preliminary assessments, and field data collection. Analysis methods and tools, and planning and design guidance for specific restoration features are also provided. This technical note is a bibliographic repository of information available to assist professionals with the process of planning, analyzing, and designing stream restoration projects. U.S. Forest Service NSAEC TN-102.4 Fort Collins, Colorado Guidance for Stream Restoration & Rehabilitation i of vi May 2018 ADVISORY NOTE Techniques and approaches contained in this technical note are not all-inclusive, nor universally applicable. -

Perennial Stream Field Identification Protocol May 2003

Perennial Stream Field Identification Protocol May 2003 This protocol defines procedures for making field determinations between perennial and intermittent streams. The protocol was developed to support fieldwork for the Fairfax County stream-mapping project. Several existing protocols were used to develop this protocol including: • Virginia Chesapeake Bay Local Assistant Department’s (CBLAD) “Very Rough Draft Guidance for Making Perennial vs. Intermittent Stream Determinations.” December 2000. • North Carolina Division of Water Quality’s “Perennial Stream Reconnaissance Protocols” January 2000. Version 2.0. (http://h2o.enr.state.nc.us/ncwetlands/strmfrm.html) • Williamsburg Environmental Group, Inc. “Qualitative Field Procedures for Perennial Stream Determinations.” [unpublished manuscript] Corresponding Author: D.A. DeBerry. • U.S. Corps of Engineers Branch Guidance Letter No 95-01: Identification of Intermittent versus Ephemeral Streams – Not Ditches. October 1994. The determination between a perennial and intermittent stream is based on the combination of hydrological, physical and biological characteristics of the stream. Field indicators of these characteristics are classed as primary or secondary and ranked using a weighted, four-tiered scoring system similar to the current system developed by the North Carolina Division of Water Quality (NCDWQ). As discussed below, a stream reach is classified as perennial based on the overall score as well as supporting information such as long term flow monitoring, presence of certain aquatic organisms, or historic information. DEFINITIONS Perennial Stream – A body of water flowing in a natural or man-made channel year-round, except during periods of drought. The term “water body with perennial flow” includes perennial streams, estuaries, and tidal embayments. Lakes and ponds that form the source of a perennial stream, or through which the perennial stream flows, are a part of the perennial stream. -

Confluence Consulting, Inc

CONFLUENCE Statement of Qualifications P.O. Box 1133, Bozeman, Montana — p. 406.585.9500 — f. 406.582.9142 www.confluenceinc.com — [email protected] CONFLUENCE SERVICES The mission at Confluence is to offer excellence in environmental design and consulting services through integrity, hard work, innovation, and customer satisfaction. Our Services: Confluence applies a multidisciplinary approach to each environmental planning, design and restoration project. We integrate the fields of fluvial geomorphology, hydrology, GIS spatial analysis and mapping, engineering, ecology, fisheries biology and botany. Our main service areas are outlined below: Stream Restoration and Channel Design Confluence provides natural stream design and bioengineering services for the restoration of streams and rivers. In addition to restoring streams to improve fish and wildlife habitat, we have engaged in the design of over a dozen stream remediation, relocation and stabilization projects involving contaminated stream beds and floodplains. Our stream channel design services include: Geomorphic channel design Hydrologic and hydraulic modeling Sediment transport modeling Bank and bed stabilization Fish habitat restoration Revegetation Floodplain and riparian restoration Endangered species protection Erosion and sediment control Watershed and Land Use Planning Confluence offers comprehensive services to address watershed planning and management needs. Our services are available at various levels of involvement, from field sampling and monitoring to -

Stream Inventory Handbook

STREAM INVENTORY HANDBOOK LEVEL I & II APPENDIX REFERENCE IN TEXT Ohanapecosh River - Gifford Pinchot NF PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION REGION 6 2010 ~ Version 2.10 Stream Inventory Handbook: Level 1 and Level II CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Introduction/Overview ......................................................................... 4 Background ............................................................................................................................ 4 Inventory Attributes ............................................................................................................... 5 Establishing Forest Priorities ................................................................................................. 6 Stream Inventory Program Management ............................................................................... 6 Program Administration And Quality Control ...................................................................... 7 A Standard Protocol ............................................................................................................... 8 Presentation of Information ................................................................................................... 9 Handbook Content ............................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2 Office Procedures Level I Inventory - Identification Level ..............12 Objectives ........................................................................................................................... -

Flow Origin, Drainage Area, and Hydrologic Characteristics for Headwater Streams in the Mountaintop Coal-Mining Region of Southern West Virginia, 2000–01

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Flow Origin, Drainage Area, and Hydrologic Characteristics for Headwater Streams in the Mountaintop Coal-Mining Region of Southern West Virginia, 2000–01 By KATHERINE S. PAYBINS Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4300 In cooperation with the U.S. Office of Surface Mining and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Charleston, West Virginia 2003 U.S. Department of the Interior GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director The use of trade or product names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Government. -------------------- For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: Chief, West Virginia District U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services 11 Dunbar Street Box 25286 Charleston, WV 25301 Denver, CO 80225-0286 CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Purpose and Scope ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 Description of Study Area..........................................................................................................................................