Onl Pub Elections Egypt 2015 Engl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egypt Daily Update-December 5: Activists Maher, Douma Referred to Court; Parties Split Over Constitutional Referendum

Egypt Daily Update-December 5: Activists Maher, Douma Referred to Court; Parties Split over Constitutional Referendum Top Stories December 5, 2013 • Activisits Maher, Douma Referred to Court • Referendum Support, Opposition Continues from Political Groups • Political Cartoon of the Day Maher, Douma Referred to Criminal Court Ahmed Maher, the founder of the 6 April Movement; Mohamed Adil, a leading member of 6 Also of Interest: April; and activist Ahmed Douma were referred to a criminal court on Thursday, with the first session to take place this upcoming Sunday. Maher and Douma are currently in prison, 29 things you need to while Adil remains free. All three are facing a number of accusations, including organizing know about Egypt’s protests without a permit, illegal assembly, blocking roads, assault on police officers, and draft constitution inciting violence. The prosecution claims that these crimes were committed during protests outside the Shura Council and Abdeeen courthouse last week. Meanwhile, a judicial source Part 3: New denied rumors that an arrest warrant had been issued for labor lawyer and activist constitution expands Haitham Mohamadein, as well as several other activists including singer Ramy Essam. social and economic rights, but grey areas “Prosecution refers three prominent activists to court,” Daily News (English) 12/5/2013 remain “UPDATE | Egypt activists referred to trial for violating protest law,” Aswat Masriya (English) 12/5/2013 Sisi ranks first in Time “Egyptian activist Haitham Mohamadein not wanted for now: -

The Muslim Brotherhood Fol- Lowing the “25 Janu- Ary Revolution”

Maria Dolores Algora Weber CEU San Pablo University THE MUSLIM BROTHERHOOD FOL- LOWING THE “25 JANU- ARY REVOLUTION”: FROM THE IDEALS OF THE PAST TO THE POLITICAL CHAL- LENGES OF THE PRESENT In the framework of the Arab Spring, as the wave of social mobilisation of 2011 has come to be known, the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt marked the beginning of a process which has deeply transformed the re- ality of many countries in the Arab World. In Egypt, the events that took place in Tahrir Square not only put an end to President Mubarak's dic- tatorship, but also paved the way for new political actors, among which the Muslim Brotherhood has played a key role. During the subsequent transition, the Brotherhood gained control of the National Assembly and positioned their leader, Mohamed Mursi, as the new President. The present debate is focused on the true democratic vocation of this move- ment and its relationship with the other social forces inside Egypt and beyond. This article intends to address these issues. To that end, it begins with an explanation as to the ideological and political evolution of the Muslim Brotherhood and its internal changes brought about by the end of the previous regime, closing with an analysis of its transnational influ- ence and the possible international aftermaths. Islam, Islamism, Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt, Arab Spring 181 INTRODUCTION n 2011, a wave of social mobilisations took place in various Arab countries and which came to be known as the “Arab Spring”. This name is undoubtedly an at- tempt to draw a comparison between the historic process that unfolded in Europe Iin the mid-nineteenth century and the events that have taken place in the Arab World. -

Das Grosse Vereinslexikon Des Weltfussballs

1 RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS ALLE ERSTLIGISTEN WELTWEIT VON 1885 BIS HEUTE AFRIKA & ASIEN BAND 1 DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS DES VEREINSLEXIKON GROSSE DAS BAND 1 AFRIKA & ASIEN RENÉ KÖBER DAS GROSSE VEREINSLEXIKON DES WELTFUSSBALLS BAND 1 AFRIKA UND ASIEN Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National- bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Copyright © 2019 Verlag Die Werkstatt GmbH Lotzestraße 22a, D-37083 Göttingen, www.werkstatt-verlag.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten Gestaltung: René Köber Satz: Die Werkstatt Medien-Produktion GmbH, Göttingen ISBN 978-3-7307-0459-2 René Köber RENÉRené KÖBERKöber Das große Vereins- DasDAS große GROSSE Vereins- LEXIKON VEREINSLEXIKONdesL WEeXlt-IFKuOßbNal lS des Welt-F ußballS DES WELTFUSSBALLSBAND 1 BAND 1 BAND 1 AFRIKAAFRIKA UND und ASIEN ASIEN AFRIKA und ASIEN Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute Alle Erstligisten der ganzen Welt von 1885 bis heute 15 00015 000 Vereine Vereine aus aus 6 6 000 000 Städten/Ortschaften und und 228 228 Ländern Ländern 15 000 Vereine aus 6 000 Städten/Ortschaften und 228 Ländern 1919 000 000 farbige Vereinslogos Vereinslogos 19 000 farbige Vereinslogos Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Stadien, Erfolge, Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, Spielerauswahl Gründungsdaten, Umbenennungen, Adressen, -

Masarykova Univerzita Brno Fakulta Sportovních Studií

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA BRNO FAKULTA SPORTOVNÍCH STUDIÍ Bakalářská práce Historie fotbalu v Africe Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Luboš Vrábel SEBS, 5. sem., rok 2009 Učo: 21389 Čestné prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci, vypracoval sám. Souhlasím, aby práce byla uložena na Masarykově univerzitě v Brně v knihovně Fakulty sportovních studií a zpřístupněna ke studijním účelům. …………………… podpis Poděkování: Děkuji za pomoc a odborné vedení při zpracování této bakalářské práce. Obsah 1. Úvod……………………………………………………………………………………5 2. Fotbal v koloniální Africe……………………………………………………………...6 2.1 Počátky kolonialismu…………………………………………………….….6 2.2 Rasismus……………………………………………………………………. 7 2.3 Koloniální společnost………………………………………………………..8 3. Fotbal a rozvoj………………………………………………………………………….9 3.1 Východ ( Etiopie, Súdán, Keňa)…………………………………………… 9 3.2 Západ ( Kamerun, Nigérie, Ghana, Kongo)………………………………… 9 3.3 Sever ( Egypt, Tunisko, Maroko)………………………………………….... 10 3.4 Jih ( Jihoafrická Republika)…………………………………………………. 10 4. Fotbal a politika………………………………………………………………………... 12 5. Africké organizace……………………………………………………………………... 15 5.1 CAF …………………………………………………………………………… 15 5.2 MYSA…………………………………………………………………………. 16 5.3 playsoccer …………………………………………………………………….. 16 6.Africké fotbalové hvězdy………………………………………………………………. 17 6.1. Didier Yves Drogba Tébily…………………………………………………… 17 6.2. Roger Milla……………………………………………………………………. 17 6.3. Mahmoud El-Khatib…………………………………………………………… 17 6.4. Samuel Eto'o Fils………………………………………………………………. 18 7.Nejslavnější Africké kluby ……………………………………………………………. 19 8.Soutěže…………………………………………………………………………………. -

The Role of Political Parties in Promoting a Culture of Good Governance in Egypt Post-2011

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2015 The role of political parties in promoting a culture of good governance in Egypt post-2011 Omar Kandil Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Kandil, O. (2015).The role of political parties in promoting a culture of good governance in Egypt post-2011 [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/60 MLA Citation Kandil, Omar. The role of political parties in promoting a culture of good governance in Egypt post-2011. 2015. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/60 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo The School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The Role of Political Parties in Promoting a Culture of Good Governance in Egypt Post-2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Public Policy and Administration Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts By Omar Kandil Supervised by Dr. Amr Hamzawy Professor , Public Policy and Administration, AUC Dr. Lisa Anderson President, AUC Dr. Hamid Ali Associate Professor & Chair, Public Policy and Administration, AUC Spring 2015 1 Acknowledgements There are a few people without which it would have been impossible for me to finish this piece of work. -

Can Egypt Transition to a Modern Day Democracy?

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 2-1-2012 Revolution and Democratization: Can Egypt Transition to a Modern Day Democracy? Kristin M. Horitski Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Horitski, Kristin M., "Revolution and Democratization: Can Egypt Transition to a Modern Day Democracy?" (2012). Honors Theses. 745. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/745 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Horitski 1 Revolution and Democratization: Can Egypt Transition to a Modern Day Democracy? Kristin Horitski Honors Thesis Horitski 2 On January 25, 2011, the world’s attention was transfixed by Egypt. The people took to the streets in a series of demonstrations and marches to protest the long-time reign of President Hosni Mubarak and demand his immediate resignation. While the protests started out as peaceful acts of civil disobedience, the Mubarak government’s response was not. Police and security forces used conventional techniques such as tear gas and water cannons on the protesters, before turning to terror tactics such as snipers, live ammunition, and thugs and criminals who terrorized the people. A couple days into the uprising, Mubarak deployed the army, but they were welcomed by the protesters and did not interfere in confrontations between the police and protesters. -

FIVB2021BU19-Dailybulletin-01.Pdf

Daily Bullen No. 01 23th AUG Tehran, 23 August 2021 BU19 WCH / Strict Adherence to the Covid-19 Guidelines Dear Participating Teams, We are very happy and grateful for your participation in this challenging tournament. As we eagerly anticipate the beginning of the championship, we would like to kindly ask you to strictly follow the Covid-19 Guidelines. We advise you to remind your players not to gather in groups in the common areas and while waiting for trasportation to the training/competition halls. Also, please avoid being close to other teams, especially in the restaurant, where many people have their masks off. The health and well-being of our athletes and all participants is our highest priority! We would also ask you to be swift and cooperative while maintaning the training schedule. Please always be sure to enter and leave the training halls on time, as our schedules are very tight! Thank you for your consideration and cooperation and best of luck in your fixtures! FIVB TECHNICAL DELEGATES FIVB Volleyball Boys' U19 World Championship VOLLEYBALL - Matches calendar No Phase Teams Date Hour City Hall 1 B CZE - COL 24-Aug-2021 10:00 Tehran Hall 1 2 C THA - BUL 24-Aug-2021 10:00 Tehran Hall 2 3 A NGR - IND 24-Aug-2021 13:00 Tehran Hall 1 4 D EGY - ARG 24-Aug-2021 13:00 Tehran Hall 2 5 B ITA - BRA 24-Aug-2021 16:00 Tehran Hall 1 6 D GER - CUB 24-Aug-2021 16:00 Tehran Hall 2 7 A IRI - GUA 24-Aug-2021 19:00 Tehran Hall 1 8 C RUS - BEL 24-Aug-2021 19:00 Tehran Hall 2 9 B BRA - BLR 25-Aug-2021 10:00 Tehran Hall 1 10 D ARG - GER 25-Aug-2021 -

8 Hassan Mostafa Zamalek SC, Egyptian Premier

8 Hassan Mostafa Zamalek SC, Egyptian Premier League (Egypt) not currently plaing for national team The profile for Hassan Mostafa Date of birth: 20.11.1979 Place of birth: Giza Age: 31 Height: 1,75 Nationality: Egypt Position: Midfield - Defensive Midfield Foot: right 352.000 £ Market value: 400.000 € Market value Details of market value National team career SN National team Matches Goals 21 Egypt 29 2 More info about Hassan Mostafa Contract until: 30.06.2011 Debut (Club): 07.08.2009* "Performance data of current season Competition Matches Goals Assists Minutes CAF-Champions League 2 - - - 1 161 Egyptian Premier League 16 2 1 - 5 1367 Total: 18 2 1 - 6 1528 Performance data for season 10/11 Competition Matches CAF-Champions League 2 - - - - - - - 1 - 161 Egyptian Premier League 16 2 - 1 7 - - - 5 684 1367 Total: 18 2 - 1 7 - - - 6 764 1528 CAF-Champions League - 10/11 pl. Match Result 1 Club Africain Tunis - Zamalek SC 4 : 2 90 2 Zamalek SC - Club Africain Tunis 2 : 1 71 70 Egyptian Premier League - 10/11 pl. Match Result 4 Zamalek SC - Ismaily SC 3 : 2 38 90 5 Zamalek SC - El Gouna FC 1 : 1 72 90 6 Smouha SC - Zamalek SC 1 : 3 x 89 88 7 Zamalek SC - Arab Contractors SC 1 : 0 90 8 Masr El Makasa - Zamalek SC 3 : 4 90 11 Zamalek SC - Masry Port Said 1 : 0 90 12 El Ahly Cairo - Zamalek SC 0 : 0 51 65 64 13 Zamalek SC - Ittehad Alexandria 4 : 3 90 14 Wadi Degla FC - Zamalek SC 0 : 2 1 90 15 Zamalek SC - Entag El Harby 0 : 0 90 16 Zamalek SC - Harras El Hodoud 2 : 1 1 90 17 Petrojet - Zamalek SC 1 : 2 1 52 90 18 Zamalek SC - Enppi Club 0 : 0 90 19 Ismaily SC - Zamalek SC 0 : 0 81 80 20 El Gouna FC - Zamalek SC 2 : 1 28 56 55 22 Arab Contractors SC - Zamalek SC 2 : 3 19 86 85 Performance data for season 08/09 Competition Matches Egyptian Premier League 14 - - - 1 - - 3 7 - 981 WM-Qualifikation Afrika 2 - - - 1 - - 2 - - 55 Total: 16 - - - 2 - - 5 7 - 1036 Egyptian Premier League - 08/09 pl. -

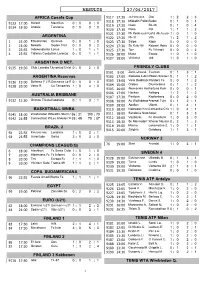

Crystal Reports Activex Designer

RESULTS 27/06/2017 AFRICA Cosafa Cup 9117 17:30 Js Hercules Otp 12: 2: 3 9118 17:30 Mikkelin PalloilSudet 01: 0: 1 9133 17:00 Malawi Mauritius 00: 0: 0 9119 17:30 Nups Bk-46 01: 0: 4 9134 19:30 Angola Tanzania 00: 0: 0 9120 17:30 Pepo Ktp 11: 1: 2 9121 17:30 Pk Keski-uusimLahti Ak./kuusy 10: 1: 0 ARGENTINA 9122 17:30 Pk-37 Vifk 12: 1: 2 1 23:00 Estudiantes Quilmes 00: 1: 0 9123 17:30 Salpa Kapa 00: 0: 0 2 23:00 Newells Godoy Cruz 00: 0: 2 9124 17:30 Sc Kufu-98 Kajaani Haka 00: 0: 0 3 23:55 Independiente Lanus 10: 1: 1 9125 17:30 Tpv Fc Viikingit 00: 0: 2 4 23:55 Talleres CordoSan Lorenzo 00: 1: 1 9126 18:00 Musa Espoo 10: 1: 0 9127 18:00 Villiketut Jbk 10: 1: 0 ARGENTINA D MET. 9135 19:30 Club Leandro NJuventud Unida00: 2: 0 FRIENDLY CLUBS 9101 9:00 Zenit-izhevsk Tyumen 01: 3: 1 ARGENTINA Reservas 9102 17:00 Zaglebie LubinPogon Szczeci 01: 1: 2 Vejle Boldklub Randers Fc 00: 1: 3 9136 15:00 Defensa Y J R.Gimnasia Lp R 00: 0: 0 9103 13:00 Orebro Djurgardens 01: 1: 2 9138 20:00 Velez R. Ca Temperley 10: 4: 0 9104 15:00 9105 16:00 Alemannia AacFortuna Koln 00: 0: 1 Hacken Aalborg AUSTRALIA BRISBANE 9106 17:00 12: 1: 2 9107 17:30 Partizan Kapfenberg 00: 2: 0 9132 12:30 Grange ThistleCapalaba 01: 3: 1 9108 18:00 Ac WolfsbergeArsenal Tula 01: 2: 1 9109 18:00 Apollon Ujpest 01: 4: 1 BASKETBALL WNBA 9110 18:00 Napredak KrusConcordia Chia10: 4: 1 9141 18:00 Washington WSeattle Storm W56: 31 100: 70 9111 18:00 Sandecja NowyApoel 01: 3: 3 9142 23:55 Connecticut WLos Angeles W39: 45 79: 87 9112 18:00 Vozdovac Fc Orenburg 10: 3: 0 9113 18:30 Sc Mannsdorf Wiener Neusta 02: 1: 3 BRAZIL 2 9114 19:00 Malmo Lokomotiva Z. -

Title: Egypt – Political Parties – Young Egypt Party

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: EGY33332 Country: Egypt Date: 12 May 2008 Keywords: Egypt – Political Parties – Young Egypt Party (Misr al-Fatah Party) This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide a list of the political parties in Egypt. 2. Are there any reports about the attempted registration of the “Independent party” or the “Young Egypt Party”? 3. Are there any reports mentioning the Independent party or the Young Egypt Party? RESPONSE 1. Please provide a list of the political parties in Egypt. Egypt’s official State Information Service website lists the following political parties in Egypt: …During Mubarak’s era, the number of political parties in Egypt has increased to reach 24 parties. According to the ballot on March 26, 2007 Article (5) was amended to prohibit the establishment of any religious party “The political system of the Arab Republic of Egypt is a multiparty system, within the framework of the basic elements and principles of the Egyptian society as stipulated in the Constitution. Political parties are regulated by law. Citizens have the right to establish political parties according to the law and no political activity shall be exercised nor political parties established on a religious referential authority, on a religious basis or on discrimination on grounds of gender or origin”. -

ICCA Report 8.Indb

INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION REPORT OF THE CROSS-INSTITUTIONAL TASK FORCE ON GENDER DIVERSITY IN ARBITRAL APPOINTMENTS AND PROCEEDINGS THE ICCA REPORTS NO. 8 2020 ICCA is pleased to present the ICCA Reports series in the hope that these occasional papers, prepared by ICCA interest groups and project groups, will stimulate discussion and debate. INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION REPORT OF THE ASIL-ICCAINTERNATIONAL COUNCIL JOINT FOR TASK FORCE ON COMMERCIAL ARBITRATION ISSUE CONFLICTS IN INVESTOR-STATE ARBITRATION REPORT OF THE CROSS-INSTITUTIONAL TASKTHE FORCE ICCA ON REPORTS GENDER DIVERSITY NO. 3 IN ARBITRAL APPOINTMENTS AND PROCEEDINGS THE17 ICCA March REPORTS 2016 NO. 8 2020 with the assistance of the Permanentwith the Courtassistance of Arbitration of the PermanentPeace Palace, Court Theof Arbitration Hague Peace Palace, The Hague www.arbitration-icca.org www.arbitration-icca.org Published by the International Council for Commercial Arbitration <www.arbitration-icca.org>, on behalf of the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings ISBN 978-94-92405-20-3 All rights reserved. © 2020 International Council for Commercial Arbitration © International Council for Commercial Arbitration (ICCA). All rights reserved. ICCA and the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings wish to encourage the use of this Report for the promotion of diversity in arbitration. Accordingly, it is permitted to reproduce or copy this Report, provided that the Report is reproduced accurately, without alteration and in a non-misleading con- text, and provided that the authorship of the Cross-Institutional Task Force on Gender Diversity in Arbitral Appointments and Proceedings and ICCA’s copyright are clearly acknowledged. -

The Role of Political Parties in Promoting a Culture of Good Governance in Egypt Post-2011

The American University in Cairo The School of Global Affairs and Public Policy The Role of Political Parties in Promoting a Culture of Good Governance in Egypt Post-2011 A Thesis Submitted to the Public Policy and Administration Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts By Omar Kandil Supervised by Dr. Amr Hamzawy Professor , Public Policy and Administration, AUC Dr. Lisa Anderson President, AUC Dr. Hamid Ali Associate Professor & Chair, Public Policy and Administration, AUC Spring 2015 1 Acknowledgements There are a few people without which it would have been impossible for me to finish this piece of work. Two of the most important women of my life top the list: my mother Amany Mohamed Abdallah and my wife-to-be Hanya El-Azzouni, who are the fuel of all of my past, present and future life’s endeavors. I must thank them and express my deepest love and gratitude to everything they have given me and their presence in my life day by day. It would have been impossible to make it through without them. You are my blessings. This thesis closes my chapter as an AUC student, a chapter which opened in 2007. This place has given me so much and I would not have been able to write this research without the numerous opportunities this institution has blessed me with. I especially wish to thank President Lisa Anderson for being a constant source of guidance, friendship, and support throughout the past years, on all levels of my AUC experience, as an undergraduate student, graduate student, staff member, and now on this work.