1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcription of LGBT Oral History 060: Colin Kreitzer

LGBT History Project of the LGBT Center of Central PA Located at Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections http://archives.dickinson.edu/ Documents Online Title: LGBT Oral History: Colin Kreitzer Date: February 16, 2017 Location: LGBT Oral History – Kreitzer, Colin – 060 Contact: LGBT History Project Archives & Special Collections Waidner-Spahr Library Dickinson College P.O. Box 1773 Carlisle, PA 17013 717-245-1399 [email protected] Interviewee: Colin Kreitzer Interviewer: Barry Loveland Videographer: Catherine McCormick Date: Thursday, February 16, 2017 Place: Colin’s home in Harrisburg Transcriber: Amanda Donoghue Proofreader: VJ Kopacki Finalized by Mary Libertin (July 2020) Abstract: Colin Kreitzer was born in 1947 in Enola, Pennsylvania, and grew up in Wormleysburg, Pennsylvania with his parents and his younger sister. He attended West Chester College and moved to Harrisburg in 1977, where he began getting involved in the gay community through activism and social activities. In this interview Colin reviews his involvement in the Gay and Lesbian Switchboard of Harrisburg, Dignity, Metropolitan Community Church, and volleyball. He also talks about the stigma of growing up as a closeted gay man, the bullying he experienced in primary and secondary school, and how he came to accept his sexuality and come out when he was in college. He discusses his past relationships and the struggles that he has experienced trying to forge healthy, emotional connections with others. Colin is also involved in Alcoholics Anonymous, he and explains the values he has gained from the organization and the changes in his own character and behavior. CM: So we are recording. BL: Okay, my name’s Barry Loveland, and I’m here with Catherine McCormick who’s our videographer, and we’re here on behalf of the LGBT Center of Central Pennsylvania History Project. -

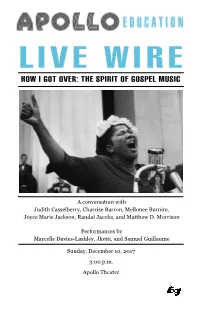

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

OF CROSSINGS and CROWDS: RE/SOUNDING SUBJECT FORMATIONS by Devon R. Kehler a Dissertation Submitted T

Of Crossings and Crowds: Re/Sounding Subject Formations Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Kehler, Devon R. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 06:11:05 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625373 OF CROSSINGS AND CROWDS: RE/SOUNDING SUBJECT FORMATIONS by Devon R. Kehler __________________________ Copyright © Devon R. Kehler 2017 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN RHETORIC, COMPOSITION AND THE TEACHING OF ENGLISH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Devon R. Kehler, titled Of Crossings and Crowds: Re/Sounding Subject Formations and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________________________________________ Date: April 14, 2017 Adela C. Licona ____________________________________________________________ Date: April 14, 2017 Maritza Cardenas ____________________________________________________________ Date: April 14, 2017 John Melillo Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

I Sing Because I'm Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy For

―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer D. M. A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Yvonne Sellers Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Loretta Robinson, Advisor Karen Peeler C. Patrick Woliver Copyright by Crystal Yvonne Sellers 2009 Abstract ―I Sing Because I‘m Free‖: Developing a Systematic Vocal Pedagogy for the Modern Gospel Singer With roots in the early songs and Spirituals of the African American slave, and influenced by American Jazz and Blues, Gospel music holds a significant place in the music history of the United States. Whether as a choral or solo composition, Gospel music is accompanied song, and its rhythms, textures, and vocal styles have become infused into most of today‘s popular music, as well as in much of the music of the evangelical Christian church. For well over a century voice teachers and voice scientists have studied thoroughly the Classical singing voice. The past fifty years have seen an explosion of research aimed at understanding Classical singing vocal function, ways of building efficient and flexible Classical singing voices, and maintaining vocal health care; more recently these studies have been extended to Pop and Musical Theater voices. Surprisingly, to date almost no studies have been done on the voice of the Gospel singer. Despite its growth in popularity, a thorough exploration of the vocal requirements of singing Gospel, developed through years of unique tradition and by hundreds of noted Gospel artists, is virtually non-existent. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Linda Davis to Matt King

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre Linda Davis From The Inside Out Country Linda Davis I Took The Torch Out Of His Old Flame Country Linda Davis I Wanna Remember This Country Linda Davis I'm Yours Country Linda Ronstadt Blue Bayou Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Different Drum Pop Linda Ronstadt Heartbeats Accelerating Country Linda Ronstadt How Do I Make You Pop Linda Ronstadt It's So Easy Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt I've Got A Crush On You Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Love Is A Rose Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Silver Threads & Golden Needles Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt That'll Be The Day Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt What's New Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt When Will I Be Loved Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt You're No Good Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville All My Life Pop / Rock Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Don't Know Much Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville When Something Is Wrong With My Baby Pop Linda Ronstadt & James Ingram Somewhere Out There Pop / Rock Lindsay Lohan Over Pop Lindsay Lohan Rumors Pop / Rock Lindsey Haun Broken Country Lionel Cartwright Like Father Like Son Country Lionel Cartwright Miles & Years Country Lionel Richie All Night Long (All Night) Pop Lionel Richie Angel Pop Lionel Richie Dancing On The Ceiling Country & Pop Lionel Richie Deep River Woman Country & Pop Lionel Richie Do It To Me Pop / Rock Lionel Richie Hello Country & Pop Lionel Richie I Call It Love Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

Use of Reflexive Thinking in Music Therapy to Understand the Therapeutic Process; Moments of Clarity, Self-Criticism: an Autoethnography

Qualitative Inquiries in Music Therapy 2018: Volume 13 (1), pp. Barcelona Publishers USE OF REFLEXIVE THINKING IN MUSIC THERAPY TO UNDERSTAND THE THERAPEUTIC PROCESS; MOMENTS OF CLARITY, SELF-CRITICISM: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHY Demeko Freeman, MMT, MT-BC ABSTRACT This research followed the phenomenological tradition to deliver an autoethnographic account of my experience as a music therapist working with people living with dementia. My aim was to challenge socio-cultural stigmas surrounding dementia as well as extend the sources of “truth” in regard to epistemological and ontological stances. The autoethnography presented a reflective examination through story of my daily life at a residential treatment facility. In this paper I explore encounters with residents and staff in an effort to better understand myself as a clinician and the therapeutic process. This process included decisions I made, the rationale for those decisions, and the evolution of the relationships. PRELUDE The Missing Person One rarely conducts research that is of no personal interest or gain. Realistically, the researcher’s influence will always be present in the research, as the foundation of the research question comes from the researcher’s personal curiosity to understand the phenomena under investigation (Muncey, 2010). The curiosity that propels research may stem from the memory of a loved one, a personal or professional interaction with another human being, or academic discourse. Aigen (2015) states that researchers, “are passionate advocates for particular theories and these theoretical commitments influence how facts are construed” (p. 12). Aigen further expresses that those in favor of a theory or stance are more likely to present findings that confirm it, while opponents of a theory will do the opposite. -

LYRICS --- M a H a L I a J a C K S O N - D I S C O G R a P H Y

1912 – 1972 LYRICS --- M a h a l i a J a c k s o n - D i s c o g r a p h y --- This third edition contains 298 lyric variants of 142 songs Copyright notice Most of the material presented in this document is retrieved from the Internet. Some information is recreated from LP sleeves and CD inlays. All this is done without any permission from the original authors. In order to publish this document or parts thereof, the permission of the original authors is required. This Document is created using OpenOffice Writer V2.4 (http://www.openoffice.org/) 2 --- M a h a l i a J a c k s o n - D i s c o g r a p h y --- Table of Contents A child of the king...............................................................6 Garden of prayer...............................................................20 A child of the king (490721C)............................................6 Give me that old-time religion..........................................20 A mighty fortress is our God...............................................6 Go tell it on the mountain..................................................21 A mighty fortress is our God (680226C)............................7 Go tell it on the mountain (501017C)...............................21 A rusty old halo...................................................................7 Go tell it on the mountain (550531C)...............................21 A rusty old halo (541122C).................................................7 Go tell it on the mountain (620724C)...............................21 A satisfied mind..................................................................7 -

Page 1 February 2016 Edition by Song Title #Icanteven (I Can't Even)

PAGE 1 FEBRUARY 2016 EDITION BY SONG TITLE #ICANTEVEN (I 31837 THE NEIGHBOURHOOD 187 VS FELIX (V) 30961 BOOTLEG CAN'T EVEN) (V) FT FRENCH MONTANA 19 YOU + ME (V) 27215 DAN & SHAY #SELFIE (V) 27946 THE CHAINSMOKERS 1901 (V) 23066 BIRDY $100 BILL (EXPLICIT) (V) 26811 JAY-Z 19-2000 (V) 24095 GORILLAZ (DON'T FEAR) THE REAPER BLUE OYSTER CULT (7 INCH EDIT) (V) 30394 1959 (V) 16532 LEE KERNAGHAN 1973 12579 JAMES BLUNT (I'D BE) A LEGEND RONNIE MILSAP IN MY TIME (V) 31396 1979 (V) 19860 SMASHING PUMPKINS (IF PARADISE IS) AMEN CORNER 1982 (V) 28398 RANDY TRAVIS HALF AS NICE (V) 32025 1983 (NINETEEN 21305 NEON TREES (WIN, PLACE OR SHOW) INTRUDERS EIGHTY THREE) (V) SHE'S A WINNER (V) 32232 1984 (V) 29718 DAVID BOWIE (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY BRITNEY SPEARS (ALBUM VERSION) (V) 31784 1985 (V) 2222 BOWLING FOR SOUP 1994 (V) 25845 JASON ALDEAN (YOU MAKE ME FEEL LIKE) 31218 ARETHA FRANKLIN A NATURAL WOMAN (V) 1999 8496 PRINCE MARTIN SOLVEIG 1999 (EXTENDED VERSION) PRINCE +1 (V) 32224 FT SAM WHITE 4347 19TH NERVOUS 0 TO 100 - THE CATCH DRAKE 9087 THE ROLLING STONES UP (EXPLICIT) (V) 30044 BREAKDOWN DESMOND DEKKER 1-LUV 6733 E-40 007 12105 & THE ACES 1ST MAN IN SPACE 23233 ALL SEEING I 1 - 2 - 3 (V) 20677 LEN BARRY (FIRST) (V) BONE THUGS N 1 2 3 O'LEARY (V) 17028 DES O'CONNOR 1ST OF THA MONTH 6874 HARMONY 1 TRAIN (V) 30741 A$AP ROCKY 2 BAD 6696 MICHAEL JACKSON 1, 2 STEP (V) 2181 CIARA FT MISSY ELLIOTT 2 BECOME 1 7451 SPICE GIRLS 1, 2, 3, 4 (SUMPIN' NEW) 7051 COOLIO 2 DOORS DOWN 13629 MYSTERY JETS 1, 2, 3, 4 (V) 3778 PLAIN WHITE T'S 2 HEARTS 12951 KYLIE MINOGUE -

The Mississippi Mass Choir

R & B BARGAIN CORNER Bobby “Blue” Bland “Blues You Can Use” CD MCD7444 Get Your Money Where You Spend Your Time/Spending My Life With You/Our First Feelin's/ 24 Hours A Day/I've Got A Problem/Let's Part As Friends/For The Last Time/There's No Easy Way To Say Goodbye James Brown "Golden Hits" CD M6104 Hot Pants/I Got the Feelin'/It's a Man's Man's Man's World/Cold Sweat/I Can't Stand It/Papa's Got A Brand New Bag/Feel Good/Get on the Good Foot/Get Up Offa That Thing/Give It Up or Turn it a Loose Willie Clayton “Gifted” CD MCD7529 Beautiful/Boom,Boom, Boom/Can I Change My Mind/When I Think About Cheating/A LittleBit More/My Lover My Friend/Running Out of Lies/She’s Holding Back/Missing You/Sweet Lady/ Dreams/My Miss America/Trust (featuring Shirley Brown) Dramatics "If You come Back To Me" CD VL3414 Maddy/If You Come Back To Me/Seduction/Scarborough Faire/Lady In Red/For Reality's Sake/Hello Love/ We Haven't Got There Yet/Maddy(revisited) Eddie Floyd "Eddie Loves You So" CD STAX3079 'Til My Back Ain't Got No Bone/Since You Been Gone/Close To You/I Don't Want To Be With Nobody But You/You Don't Know What You Mean To Me/I Will Always Have Faith In You/Head To Toe/Never Get Enough of Your Love/You're So Fine/Consider Me Z. Z. -

“I'll Fly Away”: the Music and Career of Albert E. Brumley

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 “I’LL FLY AWAY”: THE MUSIC AND CAREER OF ALBERT E. BRUMLEY Kevin Donald Kehrberg University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kehrberg, Kevin Donald, "“I’LL FLY AWAY”: THE MUSIC AND CAREER OF ALBERT E. BRUMLEY" (2010). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 49. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/49 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kevin Donald Kehrberg The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2010 “I’LL FLY AWAY”: THE MUSIC AND CAREER OF ALBERT E. BRUMLEY ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Music at the University of Kentucky By Kevin Donald Kehrberg Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Ronald Pen, Associate Professor of Musicology Lexington, Kentucky 2010 Copyright © Kevin Donald Kehrberg 2010 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION “I’LL FLY AWAY”: THE MUSIC AND CAREER OF ALBERT E. BRUMLEY Albert E. Brumley (1905-1977) was the most influential American gospel song composer of the twentieth century, penning such “classics” within the genre as “Jesus, Hold My Hand,” “I’ll Meet You in the Morning,” “If We Never Meet Again,” “Turn Your Radio On,” and “Rank Strangers to Me.” His “I’ll Fly Away” has become the most recorded gospel song in American history with over one thousand recordings to date, and several of his works transcend cultural boundaries of style, genre, race, denomination, and doctrine.