Roadless Area Conservation; National Forest Systems Land in Idaho FEIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12. Owyhee Uplands Section

12. Owyhee Uplands Section Section Description The Owyhee Uplands Section is part of the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion. The Idaho portion, the subject of this review, comprises southwestern Idaho from the lower Payette River valley in the northwest and the Camas Prairie in the northeast, south through the Hagerman Valley and Salmon Falls Creek Drainage (Fig. 12.1, Fig. 12.2). The Owyhee Uplands spans a 1,200 to 2,561 m (4,000 to 8,402 ft) elevation range. This arid region generally receives 18 to 25 cm (7 to 10 in) of annual precipitation at lower elevations. At higher elevations, precipitation falls predominantly during the winter and often as snow. The Owyhee Uplands has the largest human population of any region in Idaho, concentrated in a portion of the section north of the Snake River—the lower Boise and lower Payette River valleys, generally referred to as the Treasure Valley. This area is characterized by urban and suburban development as well as extensive areas devoted to agricultural production of crops for both human and livestock use. Among the conservation issues in the Owyhee Uplands include the ongoing conversion of agricultural lands to urban and suburban development, which limits wildlife habitat values. In addition, the conversion of grazing land used for ranching to development likewise threatens wildlife habitat. Accordingly, the maintenance of opportunity for economically viable Lower Deep Creek, Owyhee Uplands, Idaho © 2011 Will Whelan ranching operations is an important consideration in protecting open space. The aridity of this region requires water management programs, including water storage, delivery, and regulation for agriculture, commercial, and residential uses. -

Julia's Unequivocal Nevada Klampout

Julia's Unequivocal Nevada Klampout #35 JARBIDGE clamper year 6019 Brought to you by Julia C. Bulette chapter 1864, E Clampus Vitus Researched and interpreted by Jeffrey D. Johnson XNGH, Clamphistorian at chapter 1864 Envisioned by Noble Grand Humbug Bob Stransky Dedicated to Young Golddigging Widders and Old Orphans 2014 c.e. Why Why yes, Jarbidge is a ''fer piece'' from any place. This year's junk trip has the unique quirk that it is not in the Great Basin like the rest of our territory. Northern Elko County is drained by the tributaries of the Owyhee, Bruneau and Jarbidge Rivers. They flow in to the Snake River and out to the sea. To the South the range is drained by the North Fork of the Humboldt and in the East, St. Mary's River. Geology The North American Continental plate moves at a rate of one inch a year in a Southwesterly direction. Underneath the plate is a volcanic hotspot or mantle plume. 10 to 12 million years ago the hotspot was just North of the Idaho border. Over that time it has moved, leaving a trail of volcanic debris and ejectamenta from McDermitt Nevada, East. Now the Yellowstone Caldera area is over the plume. During the middle and late Miocene, a sequence of ash flows, enormous lava flows and basalt flows from 40 odd shield volcanoes erupted from the Bruneau-Jarbidge caldera. The eruptive center has mostly been filled in by lava flows and lacustrine and fluvial sediments. Two hundred Rhinos, five different species of horse, three species of cameloids, saber tooth deer and other fauna at Ashfall Fossil Beds 1000 miles downwind to the East in Nebraska, were killed by volcanic ash from the Bruneau Jarbidge Caldera. -

Silver City and Delamar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boise State University - ScholarWorks Early Records of the Episcopal Church in Southwestern Idaho, 1867-1916 Silver City and DeLamar Transcribed by Patricia Dewey Jones Boise State University, Albertsons Library Boise, Idaho Copyright Boise State University, 2006 Boise State University Albertsons Library Special Collections Dept. 1910 University Dr. Boise, ID 83725 http://library.boisestate.edu/special ii Table of Contents Foreword iv Book 1: Silver City 1867-1882 1-26 History 3 Families 3 Baptisms 4 Confirmed 18 Communicants 19 Burials 24 Book 2: Silver City 1894-1916 27-40 Communicants 29 Baptisms 32 Confirmations 37 Marriages 38 Burials 39 Book 3: DeLamar 1895-1909 41-59 Historic Notes 43 Baptisms 44 Confirmations 50 Communicants 53 Marriages 56 Burials 58 Surname Index 61 iii Foreword Silver City is located high in the Owyhee Mountains of southwestern Idaho at the headwaters of Jordan Creek in a picturesque valley between War Eagle Mountain on the east and Florida Mountain on the west at an elevation of approximately 6,300 feet. In 1863 gold was discovered on Jordan Creek, starting the boom and bust cycle of Silver City. During the peaks of activity in the local mines, the population grew to a few thousand residents with a full range of business services. Most of the mines played out by 1914. Today there are numerous summer homes and one hotel, but no year-long residents. Nine miles “down the road” from Silver City was DeLamar, another mining boom town. -

Characterization of Ecoregions of Idaho

1 0 . C o l u m b i a P l a t e a u 1 3 . C e n t r a l B a s i n a n d R a n g e Ecoregion 10 is an arid grassland and sagebrush steppe that is surrounded by moister, predominantly forested, mountainous ecoregions. It is Ecoregion 13 is internally-drained and composed of north-trending, fault-block ranges and intervening, drier basins. It is vast and includes parts underlain by thick basalt. In the east, where precipitation is greater, deep loess soils have been extensively cultivated for wheat. of Nevada, Utah, California, and Idaho. In Idaho, sagebrush grassland, saltbush–greasewood, mountain brush, and woodland occur; forests are absent unlike in the cooler, wetter, more rugged Ecoregion 19. Grazing is widespread. Cropland is less common than in Ecoregions 12 and 80. Ecoregions of Idaho The unforested hills and plateaus of the Dissected Loess Uplands ecoregion are cut by the canyons of Ecoregion 10l and are disjunct. 10f Pure grasslands dominate lower elevations. Mountain brush grows on higher, moister sites. Grazing and farming have eliminated The arid Shadscale-Dominated Saline Basins ecoregion is nearly flat, internally-drained, and has light-colored alkaline soils that are Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and America into 15 ecological regions. Level II divides the continent into 52 regions Literature Cited: much of the original plant cover. Nevertheless, Ecoregion 10f is not as suited to farming as Ecoregions 10h and 10j because it has thinner soils. -

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1

United States Department of Agriculture Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1 Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-375 April 2018 Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Ho, Joanne J.; Little, Natalie, J.; Joyce, Linda A., eds. 2018. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the Intermountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-375. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Part 1. pp. 1–197. Abstract The Intermountain Adaptation Partnership (IAP) identified climate change issues relevant to resource management on Federal lands in Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, eastern California, and western Wyoming, and developed solutions intended to minimize negative effects of climate change and facilitate transition of diverse ecosystems to a warmer climate. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service scientists, Federal resource managers, and stakeholders collaborated over a 2-year period to conduct a state-of-science climate change vulnerability assessment and develop adaptation options for Federal lands. The vulnerability assessment emphasized key resource areas— water, fisheries, vegetation and disturbance, wildlife, recreation, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services—regarded as the most important for ecosystems and human communities. The earliest and most profound effects of climate change are expected for water resources, the result of declining snowpacks causing higher peak winter -

Owyhee County Church Directory

Established 1865 OOwyheewyhee CCountyounty FairFair pphotoshotos andand results,results, SectionSection B SSchoolchool iiss aalmostlmost hhere,ere, PPageage 33AA RRimrockimrock tteachereacher hhonored,onored, PPageage 66AA Marsing rolls out menus to help State group salutes Alan Schoen students with their nutrition for inspiring FFA work VOL. 30, NO. 32 75 CENTS HOMEDALE, OWYHEE COUNTY, IDAHO WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 12, 2015 Fair culminates with coronation Former rancher, BLM Payette girl wins boss right mixture to Retiring Owyhee County Fair and Rodeo Queen Jaycee Engle of Melba places her crown on front Initiative group Payette’s Mandy Allison after the new queen was announced Jaurena ready to Saturday night in the rodeo arena. The Saturday night coronation keep agreement’s coincided with the final night of the Owyhee County Rodeo. spirit, intent Allison was chosen queen over in forefront three other contestants. She also earned the horsemanship award. Owyhee Initiative Inc. See Page 9B for a full rundown champions an agreement built by of the queen contest people from diverse backgrounds, so perhaps it’s only fi tting that a guy like Mitch Jaurena should be selected as the organization’s fi rst executive director. The retired Marine has worked as a rancher, a military attaché, a Bureau of Land Management fi eld manager and an environmental Mitch Jaurena manager. Initiative toward the goals that the Bottom line: He has the Board of County Commissioners fortitude, the environmental and had in mind at the agreement’s bureaucratic acumen and the political savvy to help push the –– See Initiative, page 5A Crapo town meetings Father shares wisdom heading for Owyhee Bruneau’s Matt Tindall gives last-minute advice to his daughter, U.S. -

Report Completed 02.13.14 by Leigh Ann Hislop, INTEL Area of Responsibility 2 DISPATCH 3

Report Completed 02.13.14 by Leigh Ann Hislop, INTEL Area of Responsibility 2 DISPATCH 3 Fire Suppression Resources 6 Fire Activity Historical Comparisons 7 Fire Activity Statistics by Agency 8 Fire Activity Boise District BLM 9 Fire Activity Boise National Forest 10 Fire Activity Idaho Department of Lands Southwest 11 Fire Activity Significant Acreage 12 Logistical Activity 14 Local Resources Activity - Crews 15 Local Resources Activity – Engines 16 Local Resources Activity – Aircraft 17 Local Resources Activity – Tanker Base 19 Fuels Management 21 Boise BLM Mitigation. Prevention. Investigation 23 Range Fire Protection Districts 26 Boise National Forest Prevention 28 Idaho Department of Lands Summary 30 Mobilization Center 33 Fire Danger Rating Areas and Map 34 Remote Automated Weather Stations 35 Fire Danger Rating Seasonal Outputs 36 Weather Summary 38 Seasonal Weather and Severity – SNOTEL Information 41 Lightning Summary 44 Fuel Moisture 45 Fuel Moisture Charts 48 1 AREA OF RESPONSIBILITY The Boise Interagency Dispatch Center continued its interagency success in providing safe, cost effective service for wildland fires within southwest Idaho for Boise District Bureau of Land Management, Boise National Forest, and Southwest Idaho Department of Lands. Listed below is the total acreage responsibility of Boise Interagency Dispatch Center and each agency’s ownership and protection areas. SOUTHWEST IDAHO BOISE DISTRICT BLM BOISE NATIONAL FOREST DEPARTMENT OF LANDS OWNERSHIP ACRES 3,826,562 2,085,828 501,392 PROTECTION ACRES 6,603,286 -

A Traditional Use Study of the Hagerman

A TRADITIONAL USE STUDY OF THE I HAGERMAN FOSSIL BEDS NATIONAL MONUMENT L.: AND OTHER AREAS IN SOUTHERN IDAHO Submitted to: Columbia Cascade System Support Office National Park Service Seattle, Washington Submitted by: L. Daniel Myers, Ph.D. Epochs· Past .Tracys Landing, Maryland September, 1998 PLEASE RETURN TO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERViCE CENTER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ii List of Figures and Tables iv Abstract v CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION l OBJECTIVES l FRAMEWORK OF STUDY 2 STUDY AREAS 4 STUDY POPULATIONS 5 DESIGN OF SUCCEEDING CHAPTERS 5 CHAPTER TWO: PROTOCOL AND STRATEGIES. 7 OBJECTIVES 7 CONTACT WITH POTENTIAL CONSULTANTS 7 SCHEDULING AND APPOINTMENTS 8 QUESTIONNAIRE 8 INTERVIEW SPECIFICS 10 CHAPTER THREE: INTERVIEW DETAILS 12 OBJECTIVES 12 SELF, FAMILY, AND ANCESTORS 12 TRIBAL DISTRIBUTIONS AND FOOD-NAMED GROUPS 13 SETTLEMENT AND SUBSISTENCE 13 FOOD RESOURCES . 14 MANUFACTURE GOODS 15 INDIAN DOCTORS, MEDICINE, AND HEALTH 15 STORIES, STORYTELLING, AND SACRED PLACES 15 CONTEMPORARY PROBLEMS AND ISSUES 16 CHAPTER FOUR: COMMUNITY SUMMARIES OF THE FIRST TIER STUDY AREAS 17 OBJECTIVES 17 DUCK VALLEY INDIAN RESERVATION 17 FORT HALL INDIAN RESERVATION 22 NORTHWESTERN BAND OF SHOSHONI NATION 23 CHAPTER FIVE: COMMUNITY SUMMARIES OF THE SECOND TIER STUDY AREAS 25 OBJECTIVES 25 DUCK VALLEY INDIAN RESERVATION 25 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Craters of the Moon 25 City of Rocks National Reserve and Bear River Massacre . 25 FORT HALL INDIAN RESERVATION 26 Craters of the Moon 26 City of Rocks . 28 Bear River Massacre ·28 NORTHWESTERN BAND OF SHOSHONI NATION 29 Craters of the Moon 29 City of Rocks . 29 Bear River Massacre 30 CHAPTER SIX: ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 31 OBJECTIVES 31 SUMMARY REVIEW 31 STUDY AREAS REVIEW 3 3 RECOMMENDATIONS 3 5 REFERENCES CITED 38 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 41 APPENDIX A 43 APPENDIX B 48 APPENDIX C 51 iii LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES Figure 1: Map of Southern Idaho showing Study Areas 3 Figure 2. -

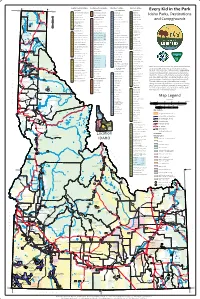

Campgrounds BOUNDARY CO

CANADA o o South-Central Idaho Southwestern Idaho Northern Idaho Eastern Idaho o 117 116 49 o 49 Burley Area Bruneau Area Coeur d’Alene Area Challis Area Every Kid in the Park «¬ Castle Rocks State Park (SP) Bruneau Sand Dunes SP Beauty Bay Bayhorse 1 CS 29 61 BS £ ¤95 Hidden K CR City of Rocks SP 1 Poison Creek Picnic Site 30 Blackwell Island 62 Challis Bridge o Idaho Parks, Destinations Lake o t e n Upper a LW Lake Wolcott SP Greater Boise Area 31 Blue Creek Bay 63 Cottonwood i Priest Lake 119 Lud Drexler Reservoir Bonneville Point 32 Blue Creek Trail 64 Deadman Hole 2 and Campgrounds BOUNDARY CO R 120 McClendon Spring Celebration Park CM Coeur d' Alene Old Mission 65 East Fork i ver 18 Harrison Campground Priest ! Lake £2 Lake Bonners ¤ 3 Clay Peak 33 Crater Lake 66 Garden Creek Milner Historic Ferry 121 PL Recreation Area 19 Cove (CJ Strike Reservoir) 34 Crater Peak 67 Herd Lake Campsite ¤£95 122 Snake River Vista 20 Dedication Point FG Farragut 68 Herd Lake Overlook Twin Falls Area EI Eagle Island SP 35 Gamlin Lake YF Land of the Yankee Fork SP Chase Lake 123 Big Cottonwood 4 8th Street Trail HB Heyburn SP «¬57 69 Jimmy Smith BONNER CO 124 Bruneau Canyon Overlook 5 Lower Hulls Gulch 36 Huckleberry Campground Trailhead Kootenai Joe T. Fallini at ! 125 Bruneau River Launch Site 6 Upper Hulls Gulch 38 Killarney Lake Boat Launch 70 Blue Sandpoint System Trail Mackay Lake ! 126 Bruneau River Take-Out 7 Miller Gulch Ridge to Rivers 39 Killarney Lake Picnic Site Priest ¤£2 71 Little Boulder P 35 end River O 127 Cedar Creek Reservoir 21 -

A Forest Mystery Solved

A FOREST MYSTERY SOLVED boys, there's a dead deer," exclaimedcovered, and apparently very fresh, probably "LOOK,Floyd Cossitt, a graduate of the Idahomade the night before or in early morning. School of Forestry in 1924 and now technicalSome of the boys recalled then having seen assistant to the Kaniksu National Forest inthese tracks on the way in but paid little at- northern Idaho, as he was escorting the Juniorstention to them.That evening at the bunk- over an old abandoned logging road. house every effort was made to assemble the The "boys"fif teen forestry students of theinformation and develop the solution.That junior class from the Idaho School of Forestryforest tragedy was enacted in many ways but on their annual two weeks' field trip to theno one was entirely satisfied with the solution. Northern Rocky Mountain Forest Experiment Cossirr GIVES EX?LANATION Station at Priest River in northern Idaho The next day, Mr. Cossitt again escorted the stopped short and there before them lay agroup, this time on a timber marking project, dead doe.Deep gashes here and there overand promised an explanation of the death of the body were evident as if a slashing, sharpthe dead deer as soon as convenient during knife had been used to mutilate the animalthe day's routine.He stated, at the proper unto death.Blood was trickling from thetime, this explanation was obtained from an wounds and from the nostrils.Wide openold-time trapper of his acquaintance and is as eyes of the dead animal seemed to show anfollows: expression of intense pain and no little amount A mother cougar was teaching her offspring of sympathy for the deer was evident on thea cougar kittento kill deer and between face of every mother's son present.The dead the two the dead doe was the result.This ac- animal was viewed in silent bewilderment forcounts for the way the ground was trampled several minutes, each man turning over theand dug up. -

Geologic Maps of the Grand View-Bruneau Area, Owyhee County, Idaho

Geologic Map of the Grand View-Bruneau Area, Owyhee County, Idaho Margaret D. Jenks Bill Bonnichsen Martha M. Godchaux Idaho Geological Survey Technical Report 98- 1 University of Idaho December 1998 Moscow, Idaho 83844-3014 Contents Introduction ............................................................... 1 Location ................................................................ 2 General Geologic Setting ........................................................ 2 Structure ................................................................ 5 Hotsprings ............................................................... 6 Acknowledgments ........................................................... 7 References ............................................................... 7 DescriptionofUnits .......................................................... 9 SedimentqUnits .......................................................... 9 Younger Unconsolidated Sediments ............................................... 9 Qal Alluvium (Holocene) .................................................. 9 Qil Intermittent lake sediments (Holocene) ......................................... 9 Qfs Fresh, unvegetated dune sand (Holocene) ....................................... 9 Qaf Alluvial fan deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) ........................ :.............. 9 Qds Vegetated dune sand (Holocene and Pleistocene) ................................... 9 Qls Landslide deposits (Holocene and Pleistocene) .................................... 9 Qbf Bonneville -

Splitting Raindrops

United States Department of Agriculture Splitting Raindrops Forest Service Intermountain Region Dixie National Administrative Facilities of the Forest Dixie National Forest, 1902-1955 May 2004 Historic Context Statement & Site Evaluations Forest Service Report No. DX-04-946 By Richa Wilson Regional Architectural Historian USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Region Cover: Harris Flat Ranger Station, 1914. "There were no improvements existing [at the Podunk Ranger Station], with the exception of the pasture fence, until 1929 when a one-room frame cabin 16' x 18' was constructed. This building was merely a shell and the pitch of roof would split a raindrop." -- Improvement Plan for Podunk Ranger Station, c1939 The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audio tape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Splitting Raindrops Administrative Facilities of the Dixie National Forest, 1902-1955 Historic Context Statement & Site Evaluations Forest Service Report No. DX-04-946 By Richa Wilson Regional Architectural Historian USDA Forest Service Intermountain Region Facilities Group 324 25th Street Ogden, UT 84401 801-625-5704 [email protected] Preface This document is a supplement to "Within A Day's Ride: Forest Service Administrative Sites in Region 4, 1891-1960," a historic and architectural history written in 2004.