The European Flood Directive: Current Implementation and Technical Issues in Transboundary Catchments, Evros / Maritsa Example

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: BULGARIA October 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Bulgaria (Republika Bŭlgariya). Short Form: Bulgaria. Term for Citizens(s): Bulgarian(s). Capital: Sofia. Click to Enlarge Image Other Major Cities (in order of population): Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Stara Zagora, Pleven, and Sliven. Independence: Bulgaria recognizes its independence day as September 22, 1908, when the Kingdom of Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. Public Holidays: Bulgaria celebrates the following national holidays: New Year’s (January 1); National Day (March 3); Orthodox Easter (variable date in April or early May); Labor Day (May 1); St. George’s Day or Army Day (May 6); Education Day (May 24); Unification Day (September 6); Independence Day (September 22); Leaders of the Bulgarian Revival Day (November 1); and Christmas (December 24–26). Flag: The flag of Bulgaria has three equal horizontal stripes of white (top), green, and red. Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early Settlement and Empire: According to archaeologists, present-day Bulgaria first attracted human settlement as early as the Neolithic Age, about 5000 B.C. The first known civilization in the region was that of the Thracians, whose culture reached a peak in the sixth century B.C. Because of disunity, in the ensuing centuries Thracian territory was occupied successively by the Greeks, Persians, Macedonians, and Romans. A Thracian kingdom still existed under the Roman Empire until the first century A.D., when Thrace was incorporated into the empire, and Serditsa was established as a trading center on the site of the modern Bulgarian capital, Sofia. -

Floods in Bulgaria

1 Floods in Bulgaria Gergov, George, Filkov, Ivan, Karagiozova, Tzviatka, Bardarska, Galia, Pencheva, Katia National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology Sofia, Bulgaria [email protected] Resume We distinguish the torrent floods of rivers as short-termed phenomena, lasting generally for only several hours and in very rare cases – for up to several days. Appropriate scientific methods for their forecasting are lacking. The short duration of the torrent floods, including their formation, do not make possible the organization of effective protection and safety measures. In many cases the inhabitants does not possess the required training to take-in urgent evacuation or adequate reaction. Torrential rainfalls of intensity up to 0.420-0.480 mm/min and duration of up to 15-29 min. predominate. The frequency of rainfalls above 0.300 mm/min accounts between 20-30 and 50-60 cases per year, while in the case of those with intensity above 0.600 mm/min the frequency diminishes to between 7-10 and 25-30 cases per year. The available hydrological information reveals, that irrespective of the ascending drought the frequency and dimensions of the torrent floods remain unchanged. The biggest flood, ever recorded in Bulgaria, was that of 31st aug.-01st sept.1858 along the Maritsa River in Bulgaria when the river banks in the town of Plovdiv have been flooded by 1-1.2 m. of water. The most ancient data for a devastating flood comes from the Turkish novelist Hadji Halfa. It concerns the Edirne (Odrin) flood in 1361. Numerous digital parameters of the floods are used in hydrology, like for instance, time of rise and time of fall of the flood, achieved water level maximum, average and maximum flow speed of the water current, size and duration of the flood, frequency and duration of the emergence, ingredient of the free water surface, time of concentration and time of travel (propagation) of the high flood wave, depth and intensity of the rainfall, state of the ground cover, preliminary moisture content of the watershed basin, etc. -

The Maritsa River

TRANSBOUNDARY IMPACTS OF MARITSA BASIN PROJECTS Text of the intervention made by Mr. Yaşar Yakış Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey During the INBO Conference Istanbul, 18 October 2012 TRASNBOUNDARY IMPACTS OF THE MARITSA BASIN PROJECTS ‐ Introduction ‐ The Maritsa River ‐ The Maritsa Basin ‐ Cooperation projects with Greece and Bulgaria ‐ Obligations under the EU acquis communautaire ‐ Need for trilateral cooperation ‐ Turkey and the Euphrates‐Tigris Basin ‐ Conclusion TRASNBOUNDARY IMPACTS OF THE MARITSA BASIN PROJECTS ‐ Introduction ‐ The Maritsa River ‐ The Maritsa Basin ‐ Cooperation projects with Greece and Bulgaria ‐ Obligations under the EU acquis communautaire ‐ Need for trilateral cooperation ‐ Turkey and the Euphrates‐Tigris Basin ‐ Conclusion TRASNBOUNDARY IMPACTS OF THE MARITSA BASIN PROJECTS ‐ Introduction ‐ The Maritsa River ‐ The Maritsa Basin ‐ Cooperation projects with Greece and Bulgaria ‐ Obligations under the EU acquis communautaire ‐ Need for trilateral cooperation ‐ Turkey and the Euphrates‐Tigris Basin ‐ Conclusion TRASNBOUNDARY IMPACTS OF THE MARITSA BASIN PROJECTS TRASNBOUNDARY IMPACTS OF THE MARITSA BASIN PROJECTS ‐ Introduction ‐ The Maritsa River ‐ 480 km long ‐ Tundzha, Arda, Ergene ‐ The Maritsa Basin ‐ Cooperation projects with Greece and Bulgaria ‐ Obligations under the EU acquis communautaire ‐ Need for trilateral cooperation ‐ Turkey and the Euphrates‐Tigris Basin ‐ Conclusion TRASNBOUNDARY IMPACTS OF THE MARITSA BASIN PROJECTS ‐ Introduction ‐ The Maritsa River ‐ The Maritsa Basin ‐ Flood potential -

Study of the Bioaccumulation of Heavy Metals in Astacus Leptodactylus in Some Areas of the Kardzhali Dam

TRADITION AND MODERNITY IN VETERINARY MEDICINE, 2018, vol. 3, No 2(5): 90–93 STUDY OF THE BIOACCUMULATION OF HEAVY METALS IN ASTACUS LEPTODACTYLUS IN SOME AREAS OF THE KARDZHALI DAM Desislava Arnaudova, Aneliya Pavlova, Atanas Arnaudov Faculty of Biology, University of Plovdiv “Paisii Hilendarski”, Plovdiv, Bulgaria E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT It is examined the contents of lead, cadmium and nickel in the water of Kardzhali dam, as well as the bioaccumulation of the heavy metals in two organs – liver and muscles of Astacus leptodactylus. In tissue samples is reported increasing of cadmium in samples of liver. The bioaccumulation coefficient was calculated on the basis of the average content of lead, cadmium and nickel in the organs of Astacus leptodactylus. We recorded that the studied crayfish are macroconcentrators for cadmium. The analyzes have shown that lake crayfish to be defined as a biomarker in toxicity testing in contami- nated waters. Key words: heavy metals, Astacus leptodactylus, crayfish, bioaccumulation. Introduction Depending on the water sites’ location by the source of contamination, different levels of lead, cadmium and nickel accumulation have been found in the tissues of crayfish (7). The concentration of heavy metals in the organs of the lake crawfish Astacus leptodactylus Eschscholtz, 1823 and other crayfish has been researched by 1, 3, 4, 6, 10, 11, 13 etc., but there are no data on the transfer of lead, cadmium and nickel in Astacus leptodactylus along the “water– crayfish” in the food chain. The research was made in different zones of the Kardzhali dam which is anthropogenically influenced by heavy metals. -

Resorts; Relocation of the RES Generation Towards the Inland; Increased Transit and Loop Flows of Electricity Through the Bulgarian Electricity Transmission Network

“Electricity System Operator” EAD State and Prospects for Development of the Bulgarian Electrical Power System Ventsislav Zahov, Head of Electrical Regimes Dept. at the National Dispatching Center The Bulgarian ELECTRICITY SYSTEM OPERATOR company performs the control of the national electrical power system, the common parallel operation with the power systems of the other ENTSO-E Member parties, provides the operation, the maintenance and the development of the electricity transmission network and administrates the electricity market 2 Electricity generation in Bulgaria during the last years Year 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Generation, GWh 43 093 44 831 42 573 46 260 50 700 47 195 43 649 47 408 49 233 Demand, GWh 35 555 36 390 34 842 36 647 38 589 37 510 36 381 37 069 37 958 Export, GWh 7 538 8 441 7 731 9 613 12 111 10 660 6 225 9 525 10 538 3 Share of the power plants in the electricity generation in 2015 Type of generation GWh NPP 15 381 Lignite TPP 21 736 Hard coal TPP 971 Gas TPP 1 867 Pumped storage 509 HPP 5 704 Wind farm 1 468 Photovoltaics 1 391 Biomass 206 Total: 49 233 4 Installed capacities by the end of 2015 Type of generation MW NPP 2000 Lignite TPP 4199 Hard coal TPP 708 Gas TPP 799 HPP 3198 Wind farm 702 Photovoltaics 1041 Biomass 64 Total: 12711 5 Registered limit values of the load during the last years Year 2013 2014 2015 2016 (by May) Regime Max. Min. Max. -

Hydrology of Maritsa and Tundzha

Hydrology of Maritsa and Tundzha The Maritsa/Meric River is the biggest river on the Balkan peninsular. Maritsa catchment is densely populated, highly industrialized and has intensive agriculture. The biggest cities are Plovdiv on the Bulgarian territory, with 650.000 citizens, and Edirne on the Turkish territory, with 231 000 citizens. The biggest tributaries are Tundzha and Arda Rivers, joining Maritsa at Edirne. Within Maritza and Tundja basin, a significant number of reservoirs and cascades were constructed for irrigation purposes, and for Hydro electricity production. The climatic and geographical characteristics of Maritsa and Tundja River Basins lead to specific run-off conditions: flash floods, high inter-annual variability, heavy soil erosion reducing the reservoirs' capacities through sedimentation, etc. The destructive forces of climatic hazards, manifesting themselves in the form of rainstorms, severe thunderstorms, intensive snowmelt, floods and droughts, appear to increase during recent years. After more than 20 years of relative minor floods during wet seasons, large floods started to occur more often since the end of the 90’s. Theses years of absence of large floods resulted in negligence of political action and financial investment for structural and non-structural flood mitigation measures and maintenance of the river bed and its embankments. 1 The morphology of both river systems is somewhat similar: Maritza flows between Pazarjik to Parvomay in a large flat plain where flood expansion would be very large if no dike contained the flows. However these dikes are not very well maintained out of the main cities, which actually protect them in a certain way ; In 2005 the large inundation upstream Plovdiv certainly prevented Maritza from overtopping the dikes in the city ! Downstream Parvomay, the relief becomes more hilly and the flood plains are more reduced in size until the Greek-Turkish borders where the plain becomes again wide and flat. -

The Political, Economic and Cultural Influences of Neo-Ottomanism in Post-Yugoslavian Countries

POLSKA AKADEMIA UMIEJĘTNOŚCI TOM XXVI STUDIA ŚRODKOWOEUROPEJSKIE I BAŁKANISTYCZNE 2017 DOI 10.4467/2543733XSSB.17.026.8324 DANUTA GIBAS-KRZAK Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa THE POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL INFLUENCES OF NEO-OTTOMANISM IN POST-YUGOSLAVIAN COUNTRIES. AN ANALYSIS ILLUSTRATED WITH SELECTED EXAMPLES Key words: neo-Ottomanism, Islamic terrorism, Turkish policy, post-Yugoslavian countries, religious fundamentalism, the Balkans, economic influence, Islamization. An ideology of neo-Ottomanism, which has become part of the Turkish foreign policy in the 21st century, dates back to the period of the rule of the Ottomans in the Balkans. However, it is difficult to distinguish Islamization from the influence of Turkish factors, but other Muslim countries are also active in the Balkans, for example, Saudi Arabia or Iran. In the 21st century, Muslim inspirations in many areas of life are noticed in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia (and in the strict sense in Bulgaria and Greece). The goal of this analysis was to show expansion of Turkish policy, defined as neo- -Ottomanism, in post-Yugoslavian countries, and its effect in the spheres of political, economic and cultural life. Therefore, the following question must be asked: do Turkish influences contribute to the specific culture of European Islam, of which goal, despite pre- vailing Islamophobia, is to disseminate ideals of tolerance between nations and religions? Does the Turkish capital contribute only to the economic development of post-Yugoslavi- an countries through investments? On the other hand, the reactivation of neo-Ottomanism may contribute to the development of radical tendencies, including religious fundamen- talism, which is, in many aspects, pose a threat to post-Yugoslavian countries. -

Flood Forecasting System for the Maritsa and Tundzha Rivers

Flood forecasting system for the Maritsa and Tundzha Rivers Arne Roelevink1, Job Udo1, Georgy Koshinchanov2, Snezhanka Balabanova2 1HKV Consultants, Lelystad, The Netherlands 2National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology, Sofia, Bulgaria Abstract Climatic and geographical characteristics of Maritsa and Tundzha River Basins lead to specific run- off conditions, which can result in extreme floods downstream, as occurred in August 2005 and March 2006. To improve the management of flood hazards, a flood forecasting system (FFS) was set up. This paper describes a forecasting system recently developed in cooperation with the National Institute for Hydrology and Meteorology (NIHM) and the East Aegean River Basin Directorate (EARBD) for the rivers Maritsa and Tundzha. The system exits of two model concepts: i) a numerical, calibrated model consisting of a hydrological part (MIKE11-NAM) and hydraulic part (MIKE11-HD) and ii) a flood forecasting system. For some basins both meteorological and discharge measurements are available. These basins are calibrated individually. The hydraulic models are calibrated based on the 2005 and 2006 floods. The hydrological and hydraulic models are combined and calibrated again. The flood forecasting system (using MIKE-Flood Watch) uses the combined calibrated hydrological and hydraulic models and produces forecasted water levels and alerts at predefined control points. The system uses the following input: • Calculated and measured water levels; • Calculated and measured river discharges; • Measured meteorological data; • Forecasted meteorological data (based on Aladin radar grid). Depending on the available input the forecast lead-time is short but accurate, or long but less accurate. If one of the input data sources is not available the system automatically uses second or third order data, which makes it extremely robust. -

Rainfall Monitoring and Discharge Forecasting

RAINFALL MONITORING AND DISCHARGE FORECASTING OVER MEDITERRANEAN BASINS IN BULGARIA Eram Artinian, Dobri Dimitrov National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology of Bulgaria – regional centre Plovdiv, Bulgarian Academy of Science [email protected] The Arda River basin is located in the Southeast part of Bulgaria. Its climate is highly influenced by the Mediterranean. For instance over 70% of the river flow of Arda River at Vehtino village is concentrated in winter-spring period. On the other hand, summer months are very dry with average river flow at basin outlet between 20 and 30 m3/sec. Three large dams forming a cascade are built in 1950s on the river bed – Kardzhaly, Studen Kladenets and Ivaylovgrad. Their total capacity is about 1 billion m3 versus mean annual inflow of about 2 billion m3. Hydrological observations were made since 1950s. There are 7 operating stations by now. The river stages are recorded on paper support by limnigraphs. Once a month the river discharges are measured by using current meters. Discharge rating curve is established for each station. 16 automatic rain gages were 2 installed in 2006 and real-time precipitation data is processed Arda River basin in Bulgaria covers about 5200 km and in every 3 h to produce fields with grid cell size of 8 km. Greece (on the right) about 600 km2. To optimize reservoir management for energy production and for limiting dam overflow an automatic rainfall monitoring network coupled with discharge forecasting system was developed. Forecasted precipitation and air temperature outputs from ALADIN with 72 h lead- time are used. -

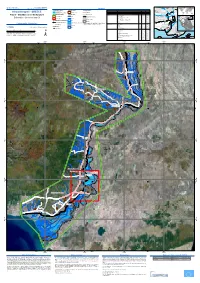

Cartographic Information Legend Delineation

GLIDE number: N/A Activation ID: EMSR499 Yugo izto chen T u Yambol Int. Charter call ID: N/A Product N.: 01ALEXANDROUPOLI, v1 Legend Plovdiv n Burgas d z Consequences within the AOI h Cris is Info rmatio n Built-Up Area Trans p o rtatio n Haskovo a Flooded Area Unit of measurement Affected Total in AOI Built-Up Area Highway Alexandro up o li - GREECE (03/02/2021 16:08 UTC) Flooded area ha 12 848.0 M Edirne Estimated population Number of inhabitants 661 NA Kardzhali ari General Info rmatio n Hydro grap hy Primary Road Ar tsa Flo o d - Situatio n as o f 03/02/2021 Built-up Residential Buildings ha 1.2 NA da Kirklareli Area of Interest River Office buildings ha 0.0 NA North Bulgaria Black Long-distance railway Adriatic Sea Wholesale and retail trade buildings ha 0.0 NA Yuzhen Sea Macedonia Delineation - Overview map 01 Detail map Stream Industrial buildings ha 0.1 NA Albania Airfield runway Evros School, university and research buildings ha 0.0 NA ts entralen ene Adminis trative b o undaries Lake Hospital or institutional care buildings ha 0.0 NA Erg Helipad Greece Aegean Turkey Military ha 0.0 NA Sea International Boundary Land Subject to Inundation Phys io grap hy & Land Us e - Land Co ver Cemetery ha 0.0 NA Tekirdag Cartographic Information ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Transportation Airfield runways ha 0.0 NA Athens Municipality Features available in the vector package Anato liki ^ Reservoir Helipad ha 0.0 NA Ionian Sea Placenames Highways km 0.2 NA Rodopi Makedo nia, Tekirdag 1:170000 Full color A1, 200 dpi resolution River Primary Road -

Politics, Religion and Gender

Politics, Religion and Gender Heated debates about Muslim women’s veiling practices have regu larly attracted the attention of European policy makers over the last decade. The headscarf has been both vehemently contested by national and/or regional gov ernments, polit ical par ties and pub lic intellectuals, and pas sion ately defended by veil wearing women and their sup porters. Systematically applying a comparative per spect ive, this book addresses the question of why the headscarf tantalizes and causes such con tro versy over issues about religious plur al ism, secularism, neutrality of the state, gender oppression, citizen ship, migration and multiculturalism. Seeking also to estab lish why the issue has become part of the regulatory practices of some Euro pean countries but not of others, this work brings together an import ant collection of in ter pretative research re gard ing the current debates on the veil in Europe, offering an interdisciplinary scope using a common research methodology, the con trib utors focus on the different religious, polit ical and cultural meanings of the veiling issue across eight coun tries and develop a comparative explanation of veiling regimes. This work will be of great inter est to students and scholars of religion and pol itics, gender studies and multiculturalism. Sieglinde Rosenberger is Professor of Political Science at the University of Vienna, Austria. Her research inter ests focus on the governance of religious plur al ism, migration and integration, identities and gender relations. Birgit Sauer is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science, University of Vienna, Austria. -

Economic Value of Ecosystem/Landscape Goods and Services in the Municipalities of Rudozem and Banite1

ГОДИШНИК НА СОФИЙСКИЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ „СВ. КЛИМЕНТ ОХРИДСКИ“ ГЕОЛОГО-ГЕОГРАФСКИ ФАКУЛТЕТ Книга 2 – ГЕОГРАФИЯ Том 109 ANNUAL OF SOFIA UNIVERSITY “ST. KLIMENT OHRIDSKI” FACULTY OF GEOLOGY AND GEOGRAPHY Book 2 – GEOGRAPHY Volume 109 ECONOMIC VALUE OF ECOSYSTEM/LANDSCAPE GOODS AND SERVICES IN THE MUNICIPALITIES OF RUDOZEM AND BANITE1 ASSEN ASSENOV, BILYANA BORISSOVA, BORISLAV GRIGOROV, PETKO BOZHKOV Катедра Ландшафтознание и опазване на природната среда Катедра Климатология, Хидрология и Геоморфология е-mail: [email protected]; asseni; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Assen Assenov, Bilyana Borissova, Borislav Grigorov, Petko Bozhkov. ECONOMIC VALUE OF ECOSYSTEM/ LANDSCAPE GOODS AND SERVICES IN THE MUNICIPALITIES OF RUDOZEM AND BANITE In the presented study of ecosystem/landscape goods and services in Rudozem and Banite municipalities, the contingent valuation method is applied by authors through a survey conducted among 121 respondents, respectively as follows: 56 respondents in Rudozem and 65 respondents in Banite. The results regarding the regulating, cultural and supporting ecosystem/landscape services for the region of Smolyan almost coincide in value with another similar study using the transfer method (Zervoudakis et al., 2007), carried out in all municipalities of the Rhodope Mountains. The regulating, cultural and supporting ecosystem ser- vices in the comparison study are defined at 5259 BGN/ha/year, a value which is very close to 5284 BGN/ha/year defined by the current study. Key words: ecosystem services; provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting services; contingent valuation method; functioning of landscapes; landscape ecology and planning. 1 This research is sponsored by the “National, European and Civilizational Dimensions of the Culture-Language- Media Dialogue” Program of the Alma Mater University Complex in the Humanities at SU “St.Kl.Ohridski, funded by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science – Bulgarian Science Fund.