S-132450 COMPLETO.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strážovské Vrchy Mts., Resort Podskalie; See P. 12)

a journal on biodiversity, taxonomy and conservation of fungi No. 7 March 2006 Tricholoma dulciolens (Strážovské vrchy Mts., resort Podskalie; see p. 12) ISSN 1335-7670 Catathelasma 7: 1-36 (2006) Lycoperdon rimulatum (Záhorská nížina Lowland, Mikulášov; see p. 5) Cotylidia pannosa (Javorníky Mts., Dolná Mariková – Kátlina; see p. 22) March 2006 Catathelasma 7 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS BIODIVERSITY OF FUNGI Lycoperdon rimulatum, a new Slovak gasteromycete Mikael Jeppson 5 Three rare tricholomoid agarics Vladimír Antonín and Jan Holec 11 Macrofungi collected during the 9th Mycological Foray in Slovakia Pavel Lizoň 17 Note on Tricholoma dulciolens Anton Hauskknecht 34 Instructions to authors 4 Editor's acknowledgements 4 Book notices Pavel Lizoň 10, 34 PHOTOGRAPHS Tricholoma dulciolens Vladimír Antonín [1] Lycoperdon rimulatum Mikael Jeppson [2] Cotylidia pannosa Ladislav Hagara [2] Microglossum viride Pavel Lizoň [35] Mycena diosma Vladimír Antonín [35] Boletopsis grisea Petr Vampola [36] Albatrellus subrubescens Petr Vampola [36] visit our web site at fungi.sav.sk Catathelasma is published annually/biannually by the Slovak Mycological Society with the financial support of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Permit of the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak rep. no. 2470/2001, ISSN 1335-7670. 4 Catathelasma 7 March 2006 Instructions to Authors Catathelasma is a peer-reviewed journal devoted to the biodiversity, taxonomy and conservation of fungi. Papers are in English with Slovak/Czech summaries. Elements of an Article Submitted to Catathelasma: • title: informative and concise • author(s) name(s): full first and last name (addresses as footnote) • key words: max. 5 words, not repeating words in the title • main text: brief introduction, methods (if needed), presented data • illustrations: line drawings and color photographs • list of references • abstract in Slovak or Czech: max. -

Development and Evaluation of Rrna Targeted in Situ Probes and Phylogenetic Relationships of Freshwater Fungi

Development and evaluation of rRNA targeted in situ probes and phylogenetic relationships of freshwater fungi vorgelegt von Diplom-Biologin Christiane Baschien aus Berlin Von der Fakultät III - Prozesswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktorin der Naturwissenschaften - Dr. rer. nat. - genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. sc. techn. Lutz-Günter Fleischer Berichter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Ulrich Szewzyk Berichter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Felix Bärlocher Berichter: Dr. habil. Werner Manz Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 19.05.2003 Berlin 2003 D83 Table of contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 MATERIAL AND METHODS .................................................................................................................. 8 1. Used organisms ............................................................................................................................. 8 2. Media, culture conditions, maintenance of cultures and harvest procedure.................................. 9 2.1. Culture media........................................................................................................................... 9 2.2. Culture conditions .................................................................................................................. 10 2.3. Maintenance of cultures.........................................................................................................10 -

Mycena Sect. Galactopoda: Two New Species, a Key to the Known Species and a Note on the Circumscription of the Section

Mycosphere 4 (4): 653–659 (2013) ISSN 2077 7019 www.mycosphere.org Article Mycosphere Copyright © 2013 Online Edition Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/4/4/1 Mycena sect. Galactopoda: two new species, a key to the known species and a note on the circumscription of the section Aravindakshan DM and Manimohan P* Department of Botany, University of Calicut, Kerala, 673 635, India Aravindakshan DM, Manimohan P 2013 – Mycena sect. Galactopoda: two new species, a key to the known species and a note on the circumscription of the section. Mycosphere 4(4), 653–659, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/4/4/1 Abstract Mycena lohitha sp. nov. and M. babruka sp. nov. are described from Kerala State, India and are assigned to sect. Galactopoda. Comprehensive descriptions, photographs, and comparisons with phenetically similar species are provided. A key is provided that differentiates all known species of the sect. Galactopoda. The circumscription of the section needs to be expanded to include some of the species presently assigned to it including the new species described here and a provisional, expanded circumscription of the section is followed in this paper. Key words – Agaricales – Basidiomycota – biodiversity – Mycenaceae – taxonomy Introduction Section Galactopoda (Earle) Maas Geest. of the genus Mycena (Pers.) Roussel (Mycenaceae, Agaricales, Basidiomycota) comprises species with medium-sized basidiomata with stipes that often exude a fluid when cut, exhibit coarse whitish fibrils at the base, and turn blackish when dried. Additionally they have ellipsoid and amyloid basidiospores, cheilocystidia that are generally fusiform and often with coloured contents, and hyphae of the pileipellis and stipitipellis covered with excrescences and diverticulate side branches. -

Pear Trellis Rust, a New Disease

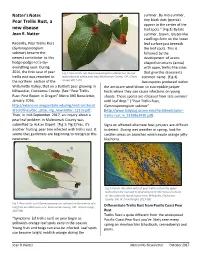

Natter’s Notes summer. By mid-summer, Pear Trellis Rust, a tiny black dots (pycnia) appear in the center of the new disease leaf spots.” [Fig 3] By late Jean R. Natter summer, brown, blister-like swellings form on the lower Recently, Pear Trellis Rust leaf surface just beneath (Gymnosporangium the leaf spots. This is sabinae) became the followed by the newest contributor to this development of acorn- hodge-podge-let’s-try- shaped structures (aecia) everything year. During with open, trellis-like sides 2016, the first case of pear Fig 1: Pear trellis rust (Gymnosporangium sabinae) on the top that give this disease its trellis rust was reported in leaf surface of edible pear tree; Multnomah County, OR. (Client common name. (Fig 4) the northern section of the image; 2017-09) Aeciospores produced within Willamette Valley, that on a Bartlett pear growing in the aecia are wind-blown to susceptible juniper Milwaukie, Clackamas County. (See “Pear Trellis hosts where they can cause infections on young Rust: First Report in Oregon” Metro MG Newsletter, shoots. These spores are released from late summer January 2016; until leaf drop.” (“Pear Trellis Rust, http://extension.oregonstate.edu/mg/metro/sites/d Gymnosporangium sabinae” efault/files/dec_2016_mg_newsletter_12116.pdf. (http://www.ladybug.uconn.edu/FactSheets/pear- Then, in mid-September 2017, an inquiry about a trellis-rust_6_2329861430.pdf) pear leaf problem in Multnomah County was submitted to Ask an Expert. [Fig 1; Fig 2] Yes, it’s Signs on affected alternate host junipers are difficult another fruiting pear tree infected with trellis rust. It to detect. -

SOMA News March 2011

VOLUME 23 ISSUE 7 March 2011 SOMA IS AN EDUCATIONAL ORGANIZATION DEDICATED TO MYCOLOGY. WE ENCOURAGE ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS BY SHARING OUR ENTHUSIASM THROUGH PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AND GUIDED FORAYS. WINTER/SPRING 2011 SPEAKER OF THE MONTH SEASON CALENDAR March Connie and Patrick March 17th » Meeting—7pm —“A Show and Tell”— Sonoma County Farm Bureau Speaker: Connie Green & Patrick March 17th—7pm Hamilton Foray March. 19th » Salt Point April April 21st » Meeting—7pm Sonoma County Farm Bureau Speaker: Langdon Cook Foray April 23rd » Salt Point May May 19th » Meeting—7pm Sonoma County Farm Bureau Speaker: Bob Cummings Foray May: Possible Morel Camping! eparated at birth but from the same litter Connie Green and Patrick Hamilton have S traveled (endured?) mushroom journeys together for almost two decades. They’ve been to the humid and hot jaguar jungles of Chiapas chasing tropical mushrooms and to EMERGENCY the cloud forests of the Sierra Madre for boletes and Indigo milky caps. In the cold and wet wilds of Alaska they hiked a spruce and hemlock forest trail to watch grizzly bears MUSHROOM tearing salmon bellies just a few yards away. POISONING IDENTIFICATION In the remote Queen Charlotte Islands their bush plane flew over “fields of golden chanterelles,” landed on the ocean, and then off into a zany Zodiac for a ride over a cold After seeking medical attention, contact and roiling sea alongside some low flying puffins to the World Heritage Site of Ninstints. Darvin DeShazer for identification at The two of them have gazed at glaciers and berry picked on muskeg bogs. More than a (707) 829-0596. -

First Report of Albifimbria Verrucaria and Deconica Coprophila (Syn: Psylocybe Coprophila) from Field Soil in Korea

The Korean Journal of Mycology www.kjmycology.or.kr RESEARCH ARTICLE First Report of Albifimbria verrucaria and Deconica coprophila (Syn: Psylocybe coprophila) from Field Soil in Korea 1 1 1 1 1 Sun Kumar Gurung , Mahesh Adhikari , Sang Woo Kim , Hyun Goo Lee , Ju Han Jun 1 2 1,* Byeong Heon Gwon , Hyang Burm Lee , and Youn Su Lee 1 Division of Biological Resource Sciences, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Korea 2 Divison of Food Technology, Biotechnology and Agrochemistry, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Korea *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT During a survey of fungal diversity in Korea, two fungal strains, KNU17-1 and KNU17-199, were isolated from paddy field soil in Yangpyeong and Sancheong, respectively, in Korea. These fungal isolates were analyzed based on their morphological characteristics and the molecular phylogenetic analysis of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rDNA sequences. On the basis of their morphology and phylogeny, KNU17-1 and KNU17-199 isolates were identified as Albifimbria verrucaria and Deconica coprophila, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, A. verrucaria and D. coprophila have not yet been reported in Korea. Thus, this is the first report of these species in Korea. Keywords: Albifimbria verrucaria, Deconica coprophila, Morphology OPEN ACCESS INTRODUCTION pISSN : 0253-651X The genus Albifimbria L. Lombard & Crous 2016 belongs to the family Stachybotryaceae of Ascomycotic eISSN : 2383-5249 fungi. These fungi are characterized by verrucose setae and conidia bearing a funnel-shaped mucoidal Kor. J. Mycol. 2019 September, 47(3): 209-18 https://doi.org/10.4489/KJM.20190025 appendage [1]. -

Forest Fungi in Ireland

FOREST FUNGI IN IRELAND PAUL DOWDING and LOUIS SMITH COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development Arena House Arena Road Sandyford Dublin 18 Ireland Tel: + 353 1 2130725 Fax: + 353 1 2130611 © COFORD 2008 First published in 2008 by COFORD, National Council for Forest Research and Development, Dublin, Ireland. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from COFORD. All photographs and illustrations are the copyright of the authors unless otherwise indicated. ISBN 1 902696 62 X Title: Forest fungi in Ireland. Authors: Paul Dowding and Louis Smith Citation: Dowding, P. and Smith, L. 2008. Forest fungi in Ireland. COFORD, Dublin. The views and opinions expressed in this publication belong to the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of COFORD. i CONTENTS Foreword..................................................................................................................v Réamhfhocal...........................................................................................................vi Preface ....................................................................................................................vii Réamhrá................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements...............................................................................................ix -

Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area

Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area • Giuseppe Venturella Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Edited by Giuseppe Venturella Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Diversity www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Editor Giuseppe Venturella MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Giuseppe Venturella University of Palermo Italy Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Diversity (ISSN 1424-2818) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity/special issues/ fungal diversity). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03936-978-2 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03936-979-9 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Giuseppe Venturella Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Reprinted from: Diversity 2020, 12, 253, doi:10.3390/d12060253 .................... 1 Elias Polemis, Vassiliki Fryssouli, Vassileios Daskalopoulos and Georgios I. -

Preliminary Classification of Leotiomycetes

Mycosphere 10(1): 310–489 (2019) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes Ekanayaka AH1,2, Hyde KD1,2, Gentekaki E2,3, McKenzie EHC4, Zhao Q1,*, Bulgakov TS5, Camporesi E6,7 1Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650201, Yunnan, China 2Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 3School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai, 57100, Thailand 4Landcare Research Manaaki Whenua, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand 5Russian Research Institute of Floriculture and Subtropical Crops, 2/28 Yana Fabritsiusa Street, Sochi 354002, Krasnodar region, Russia 6A.M.B. Gruppo Micologico Forlivese “Antonio Cicognani”, Via Roma 18, Forlì, Italy. 7A.M.B. Circolo Micologico “Giovanni Carini”, C.P. 314 Brescia, Italy. Ekanayaka AH, Hyde KD, Gentekaki E, McKenzie EHC, Zhao Q, Bulgakov TS, Camporesi E 2019 – Preliminary classification of Leotiomycetes. Mycosphere 10(1), 310–489, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/7 Abstract Leotiomycetes is regarded as the inoperculate class of discomycetes within the phylum Ascomycota. Taxa are mainly characterized by asci with a simple pore blueing in Melzer’s reagent, although some taxa have lost this character. The monophyly of this class has been verified in several recent molecular studies. However, circumscription of the orders, families and generic level delimitation are still unsettled. This paper provides a modified backbone tree for the class Leotiomycetes based on phylogenetic analysis of combined ITS, LSU, SSU, TEF, and RPB2 loci. In the phylogenetic analysis, Leotiomycetes separates into 19 clades, which can be recognized as orders and order-level clades. -

<I>Psilocybe</I> Ss in Thailand

ISSN (print) 0093-4666 © 2012. Mycotaxon, Ltd. ISSN (online) 2154-8889 MYCOTAXON http://dx.doi.org/10.5248/119.65 Volume 119, pp. 65–81 January–March 2012 Psilocybe s.s. in Thailand: four new species and a review of previously recorded species Gastón Guzmán1*, Florencia Ramírez Guillén1, Kevin D. Hyde2,3 & Samantha C. Karunarathna2,4 1 Instituto de Ecología, Apartado Postal 63, Xalapa 91070, Veracruz, Mexico 2 School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, 333 Moo 1, Tasud, Muang, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand 3Botany and Microbiology Department, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 4Mushroom Research Foundation, 128 M.3 Ban Pa Deng T. Pa Pae, A. Mae Taeng, Chiang Mai 50150, Thailand * Correspondence to: [email protected] Abstract — Psilocybe deconicoides, P. cubensis, P. magnispora, P. samuiensis, and P. thailandensis (previously known from Thailand) are revisited, andP. thaiaerugineomaculans, P. thaicordispora, P. thaiduplicatocystidiata, and P. thaizapoteca are described as new species. These new species are bluing and belong to sectionsCordisporae , Stuntzae, and Zapotecorum. Following the recent conservation of Psilocybe as the generic name for bluing species, P. deconicoides, which does not blue upon bruising, is transferred to Deconica, while the bluing taxa P. cubensis (sect. Cubensae), P. magnispora and P. thailandensis (sect. Neocaledonicae), and P. samuiensis (sect. Mexicanae) remain in Psilocybe. Key words — hallucinogenic mushrooms, richness mycobiota, Strophariaceae, tropics Introduction The hallucinogenic fungal species in Thailand, as in most tropical countries, are poorly known, which is in direct contrast with the large fungal diversity that occurs throughout the tropics. Moreover, with considerable destruction of tropical habitats for use as agricultural or cattle farms, many species will likely disappear before being documented. -

Evolutionary Relationships Among Species of 'Magic' Mushrooms Shed Light on Fungi 6 August 2013

Family matters: Evolutionary relationships among species of 'magic' mushrooms shed light on fungi 6 August 2013 "Magic" mushrooms are well known for their According to the authors, their analysis of various hallucinogenic properties. Until now, less has been morphological traits of the mushrooms suggests known about their evolutionary development and that these typically weren't acquired through a most how they should be classified in the fungal Tree of recent common ancestor and must have evolved Life. New research helps uncover the evolutionary independently or undergone several evolutionary past of a fascinating fungi that has wide losses, probably for ecological reasons. recreational use and is currently under Nevertheless, species of Psilocybe are united to investigation for a variety of medicinal applications. some degree because they have the psychedelic compound psilocybin and other secondary metabolites, or products of metabolism. The In the 19th century, the discovery of hallucinogenic authors say that former Psilocybe species that lack mushrooms prompted research into the these secondary metabolites could also be found in mushrooms' taxonomy, biochemistry, and historical Deconica. usage. Gastón Guzmán, a world authority on the genus Psilocybe, began studying its taxonomy in More information: The paper, titled "Phylogenetic the 1950s. In 1983, these studies culminated in a inference and trait evolution of the psychedelic monograph, which is currently being updated as a mushroom genus Psilocybe sensu lato team of researchers from the University of (Agaricales)," was published today in the journal Guadalajara and the University of Tennessee Botany. www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/a … collaborate with Guzmán to produce a hypothesis 0.1139/cjb-2013-0070 on how these mushrooms evolved. -

Pear Trellis Rust

Dr. Yonghao Li Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8601 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes PEAR TRELLIS RUST Pear trellis rust (European pear rust) is one premature defoliation, significant diebacks, of most devastating diseases on fruit and and reduced tree vigour (Figure 1). ornamental pear trees in Europe. In the United States, since the disease was first SYMPTOMS AND DIAGNOSTICS reported in the Bellingham, WA in 1997, it The disease affects pear and juniper plants, has moved from the west coast to east coast. which is the alternate host of the fungal In Connecticut, pear trellis rust was first pathogen Gymnosporangium sabinae. On reported in 2012. Although the disease is pear trees, the disease mainly damages considered cosmetic on pear trees, heavy and leaves although twigs and fruit can also be repeated infections due to wet spring infected. The initial symptom appears as weather conditions may result in severe yellow spots on the upper side of young leaves in the spring. Lesions become reddish orange in color and expand up to 3/4 inch in diameter (Figure 2). By mid summer, small black dots (spermagonia) form in the center of the spot on the upper side of leaves. And then, light brown, Figure 1. Browning of leaves and early Figure 2. Reddish-brown lesions on the defoliation of heavily infected pear trees in upper- (left) and lower-side (right) of the early summer leaf acorn-shaped structures (aecia) form on the differences in susceptibility between under side of the leaf directly below the varieties.