An Analysis of the Navy's Fiscal Year 2019 Shipbuilding Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Always a Marine” Men’S Hoodie for Me City State Zip in the Size Indicated Below As Described in This Announcement

MAGAZINE OF THE MARINES 4 1 0 2 LY U J Leathernwwew.mca-marcines.org/lekatherneck Happy Birthday, America Iraq 2004: Firefghts in the “City of Mosques” Riding With the Mounted Color Guard Settling Scores: The Battle to Take Back Guam A Publication of the Marine Corps Association & Foundation Cov1.indd 1 6/12/14 12:04 PM Welcome to Leatherneck Magazine’s Digital Edition July 2014 We hope you are continuing to enjoy the digital edition of Leatherneck with its added content and custom links to related information. Our commitment to expanding our digital offerings continues to refect progress. Also, access to added content is available via our website at www.mca- marines.org/leatherneck and you will fnd reading your Leatherneck much easier on smartphones and tablets. Our focus of effort has been on improving our offerings on the Internet, so we want to hear from you. How are we doing? Let us know at: [email protected]. Thank you for your continuing support. Semper Fidelis, Col Mary H. Reinwald, USMC (Ret) Editor How do I navigate through this digital edition? Click here. L If you need your username and password, call 1-866-622-1775. Welcome Page Single R New Style.indd 2 6/12/14 11:58 AM ALWAYS FAITHFUL. ALWAYS READY. Cov2.indd 1 6/9/14 10:31 AM JULY 2014, VOL. XCVII, No. 7 Contents LEATHERNECK—MAGAZINE OF THE MARINES FEATURES 10 The In-Between: Touring the Korean DMZ 30 100 Years Ago: Marines at Vera Cruz By Roxanne Baker By J. -

Mary Ellen Jukoski

EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND: Academic Degrees: Ed.D. The University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee. Curriculum and Instruction, Higher Education, 1983. Dissertation: “Accreditation of Selected Non-Traditional Colleges and Universities.” M.A. College of St. Rose, Albany, New York. English, 1979. M.S. State University of New York at Albany, Albany, New York. Curriculum Planning and Development, 1974. B.A. College of St. Rose, Albany, New York. English/Secondary Education. Cum Laude, 1973. ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE: 1995-Present: President, Mitchell College, New London, Connecticut 1994-1995: Acting President and Academic Vice President, Mitchell College, New London, Connecticut 1990-1995: Academic Vice President and Dean of the College, Mitchell College, New London, Connecticut 1988-1990: Assistant Vice President for Academic Instruction, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut 1985-1988: Dean of Continuing Education, Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut 1983-1985: Director, University Without Walls Program, Loretto Heights College, Denver, Colorado 1981-1983: Associate Director, National Institute of Mental Health Federal Grant Project, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee 1980-1983: Staff Member, Center for the Study of Higher Education, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee 1980-1981: Program Assistant, Institute for Academic Improvement, Center for the Study of Higher Education, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee 1979-1980: Assistant Executive Dean, World University-Miami, Miami, Florida 1977-1979: Assistant -

The Newsletter of the Bigelow Center for Senior Activities MARCH 2021 100 Mona Terrace, Fairfield CT 06824 203-256-3166

The Newsletter of the Bigelow Center for Senior Activities MARCH 2021 100 Mona Terrace, Fairfield CT 06824 203-256-3166 www.fairfieldct.org/bigelowcenter Mark Albertson presents: St. Patrick’s Drive-thru Luncheon Battleship Connecticut and the Great White Fleet Tuesday, March 16 at 12:00 Noon Wednesday, March 10 at 10:00 We’ve missed you! Join us, from the safety of The USS Connecticut was launched as the flagship of a new class of heavy your car, for a traditional St. Patrick’s Day lunch battleships intended to show off a new era of American naval dominance in the of Corned Beef and Cabbage. Reservations are early 20th century. These battleships were the hallmark of President Theodore required by Friday, March 12. Roosevelt’s signature initiative to modernize the American navy. A handsome Drive-thru only—PLEASE STAY IN YOUR vessel with beautiful gilded scroll work adorning its white steel bow, it was the CAR. No walk-ups please. To register go to fourth U.S. Navy vessel named after the state of Connecticut. In 1907, she led a MyActiveCenter or if you need assistance email flotilla of newly-built Navy warships, colloquially known as the “Great White [email protected]. Fleet,” on a tour around the world intended to spread American goodwill and underscore the United States’ role as a major naval power. Irish Fun Facts and Trivia Mark Albertson presents: Golda Meir Wednesday, March 17 at 3:00 Wednesday, March 24 at 10:00 You don’t get more Irish than Jay Kiley from Whether women are better than men I cannot say – but I can Synergy HomeCare.! Join him for an afternoon of say they are certainly no worse.” – Golda Meir fun facts and trivia. -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships. -

Steel Navy Website

A Sailor's Life in the New Steel Navy Home Page Banner Credits: Navy Logo from cover of Lawrence, W.J. The United States Navy Illustrated. New York, NY: The Continent Publishing Company, 1898. Sailor images from Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 94006 and NH 101116 At the dawn of the 20thwww.steelnavy.org century, the United States Navy was in the midst of a revolutionary technological transformation. The obsolete wooden sailing ships of the post-Civil War Navy, with their underpowered auxiliary steam engines, were swept away, and replaced by steel-hulled warships with powerful steam engines. This New Steel Navy was the first step in the long process that would eventually lead the United States Navy to a position of world dominance. This website examines the lives of the men who made that transformation possible – the officers and enlisted sailors of the Navy. They lived a life that was rugged and frequently dangerous, a life that was transformed by the new technologies of the ships they served on. They fought battles at sea, and even on land. They existed in a physically claustrophobic, yet socially divided world that adhered to naval traditions both old and new. They endured these hardships, and enjoyed brief moments of fun whenever possible. Pay a visit to an often overlooked moment in time, and get to know the sailors of the New Steel Navy. Video Credits: Title cards created in Photoshop, using graphics from cover of Lawrence, W.J. The United States Navy Illustrated. New York, NY: The Continent Publishing Company, 1898. -

World Cruise of the "Great White Fleet" December 1907 - February 1909 Ships

contact | about us Home | News & Events | Resources & Research | Museums | Visit | Support Us | Education Programs | Veterans | Fleet World Cruise of the "Great White Fleet" December 1907 - February 1909 Ships During the first leg of the voyage the Fleet included four divisions of four battleships each, six destroyers and five auxiliaries: First Division (RAdm. R.D. Evans): Battleships Connecticut (Fleet and Division Flagship), Kansas, Vermont, Louisiana. Second Division (RAdm. W.H. Emory): Battleships Georgia (Division Flagship), New Jersey, Rhode Island, Virginia. Third Division (RAdm. C.M. Thomas): Battleships Minnesota (Division Flagship), Ohio, Missouri, Maine. Fourth Division (RAdm. C.S. Sperry): Battleships Alabama (Division Flagship), Illinois, Kearsarge, Kentucky. Torpedo Flotilla: Destroyers Whipple, Truxtun, Lawrence, Stewart, Hopkins, Hull, and the Auxiliary Arethusa. Other Auxiliaries included: Store Ships Culgoa and Glacier; Repair Ship Panther and the dispatch vessel Yankton. There were several changes after the Atlantic Fleet arrived on the U.S. West Coast. In addition to replacement of some of the commanders by other officers, two former Pacific Fleet battleships were substituted for the uneconomical steamers Maine and Alabama, the torpedo flotilla was detached, and a hospital ship added. The fleet's composition then became: First Division (RAdm. C.S. Sperry): Battleships Connecticut (Fleet and Dvision Flagship), Kansas, Vermont, Minnesota. Second Division (RAdm. R. Wainwright): Battleships Georgia (Division Flagship), Nebraska, New Jersey, Rhode Island<. Third Division (RAdm. W.H. Emory): Battleships Louisiana (Division Flagship), Virginia, Ohio, Missouri. Fourth Division (RAdm. S. Schroeder): Battleships Wisconsin (Division Flagship), Illinois, Kearsarge, Kentucky Auxiliaries: Store Ships Culgoa and Glacier; Repair Ship Panther, dispatch vessel Yankton and Hospital Ship Relief. -

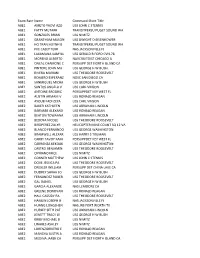

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

What Do Aoes Do When They Are Deployed? Center for Naval Analyses

CAB D0000255.A1 / Final May 2000 What Do AOEs Do When They Are Deployed? Burnham C. McCaffree, Jr. • Jay C. Poret Center for Naval Analyses 4401 Ford Avenue • Alexandria, Virginia 22302-1498 Copyright CNA Corporation/Scanned October 2002 Approved for distribution: May 2000 ,*&. KW^f s£^ ••—H. Dwight Lydtis, Jr.rDfffector USMC & Expeditionary Systems Team Acquisition, Technology & Systems Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED For copies of this document, call the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section (703) 824-2130 Copyright © 2000 The CNA Corporation What Do AOEs Do When They Are Deployed? The Navy has twelve aircraft carriers and eight fast combat support ships (AOEs) that were built to act as carrier battle group (CVBG) station ships. The multi-product AOE serves as a "warehouse" for fuel, ammunition, spare parts, provisions, and stores to other CVBG ships, especially the carrier. Currently, an AOE deploys with about four out of every five CVBGs on peacetime forward deployments. Prior to 1996, when there were only four AOEs, only two of every five CVBGs deployed with an AOE. That frequency could resume in the latter part of this decade when AOE-1 class ships are retired at the end of their 35-year service life. The combat logistics force (CLF) that supports forward deployed combatant ships consists of CVBG station ships and shuttle ships (oilers, ammunition ships, and combat stores ships) that resupply the station ships and the combatants as well. -

NAVY AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Cost-Effectiveness of Conventionally and Nuclear-Powered Carriers

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Requesters August 1998 NAVY AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Cost-Effectiveness of Conventionally and Nuclear-Powered Carriers GAO/NSIAD-98-1 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-259298 August 27, 1998 The Honorable Ted Stevens Chairman The Honorable Daniel K. Inouye Ranking Minority Member Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations United States Senate The Honorable C.W. Bill Young Chairman The Honorable John P. Murtha Ranking Minority Member Subcommittee on National Security Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives The aircraft carrier forms the building block of the Navy’s forward deployed peacetime presence, crisis response, and war-fighting forces. The nuclear-powered carrier is the most expensive weapon system in the Nation’s arsenal and represents a significant portion of the Navy’s shipbuilding and conversion future years defense program. As requested, this report discusses the cost-effectiveness to the Navy of using conventionally and nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. As the Defense Department and the Navy assess design concepts for a new class of carriers, they will evaluate a number of factors, including different propulsion types. This report contains information and analysis that you may find useful in the process of allocating future defense resources. We are sending copies of this report to the Secretaries of Defense, Navy, Energy, and State and the Director, Office of Management and Budget. Copies will also be made available to others on request. Please contact me on (202) 512-3504 if you or your staff have any questions concerning this report. -

China's Global Navy—Today's Challenge for the United States And

Naval War College Review Volume 73 Number 4 Autumn 2020 Article 4 2020 China’s Global Navy—Today’s Challenge for the United States and the U.S. Navy James E. Fanell U.S. Navy (Ret.) Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Fanell, James E. (2020) "China’s Global Navy—Today’s Challenge for the United States and the U.S. Navy," Naval War College Review: Vol. 73 : No. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol73/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fanell: China’s Global Navy—Today’s Challenge for the United States and t Captain James E. Fanell, USN (Ret.), concluded a career of nearly thirty years as a naval intelligence officer specializing in Indo-Pacific security affairs, with an emphasis on China’s navy and operations. He most recently served as the director of intelligence and information operations for the U.S. Pacific Fleet. He is a Government Fellow with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy and the creator and manager of the Indo-Pacific security forum Red Star Rising. Naval War College Review, Autumn 2020, Vol. 73, No. 4 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2020 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. -

Cathodic Protection NOD, Phase I Uniform National Discharge

This document is part of Appendix A, Cathodic Protection: Nature of Discharge for the “Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS),” published in April 1999. The reference number is EPA-842-R-99-001. Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS) Appendix A Cathodic Protection: Nature of Discharge April 1999 NATURE OF DISCHARGE REPORT Cathodic Protection 1.0 INTRODUCTION The National Defense Authorization Act of 1996 amended Section 312 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (also known as the Clean Water Act (CWA)) to require that the Secretary of Defense and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) develop uniform national discharge standards (UNDS) for vessels of the Armed Forces for “...discharges, other than sewage, incidental to normal operation of a vessel of the Armed Forces, ...” [Section 312(n)(1)]. UNDS is being developed in three phases. The first phase (which this report supports), will determine which discharges will be required to be controlled by marine pollution control devices (MPCDs)—either equipment or management practices. The second phase will develop MPCD performance standards. The final phase will determine the design, construction, installation, and use of MPCDs. A nature of discharge (NOD) report has been prepared for each of the discharges that has been identified as a candidate for regulation under UNDS. The NOD reports were developed based on information obtained from the technical community within the Navy and other branches of the Armed Forces with vessels potentially subject to UNDS, from information available in existing technical reports and documentation, and, when required, from data obtained from discharge samples that were collected under the UNDS program. -

ED 041 803 BUREAU NO CONTRACT GRANT EDRS PRICE DESCRIPTORS DOCUMENT RESUME SO 000 164 Jamieson, Alfred Ideals Awl Reality In

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 041 803 24 SO 000 164 AUTHOR Jamieson, Alfred TITLE Ideals awl Reality in Foreign Policy: American Intervention in the Caribbean. Teacher and Student Manuals. INSTITUTION Amherst Coll., Mass. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. BUREAU NO BR-5-1071 PUB DATE 69 CONTRACT OEC-5-10-158 GRANT OEG-0-9-510158-2310 NOTE 84p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$4.30 DESCRIPTORS American History, Case Studies, *Democratic Values, *Foreign Policy, Foreign Relations, Inductive Methods, Instructional Materials, *International Education, Latin American Culture, Moral Values, *Secondary Grades, Social Studies Units, *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Caribbean, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nicaragua ABSTRACT Centering around case studies of American military intervention (1898 to 1933) in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Nicaragua, this unit invites the student to compare the results of such intervention with the foreign policy goals and ideals the interventions were intended to implement. It confronts him with the dilemma of power in international affairs, with the difficulties inherent in executing foreign policy, with the problem of misunderstanding and misinterpretation caused by differences in culture, and with the question o f the morality and the efficacyof the use of force in international problem-solving. The unit has been designed primarily for college-bound students. (SeeSO 000 161 for a listing of related documents.)(Author/SBE) ir EXPERIMENTAL MATERIAL SUBJECT TO REVISION U,S, DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,