Detainee Mistreatment and Rendition: 2001–2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrities As Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field

Celebrities as Political Representatives: Explaining the Exchangeability of Celebrity Capital in the Political Field Ellen Watts Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics 2018 Declaration I, Ellen Watts, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Ellen Watts September 17, 2018. 2 Abstract The ability of celebrities to become influential political actors is evident (Marsh et al., 2010; Street 2004; 2012, West and Orman, 2003; Wheeler, 2013); the process enabling this is not. While Driessens’ (2013) concept of celebrity capital provides a starting point, it remains unclear how celebrity capital is exchanged for political capital. Returning to Street’s (2004) argument that celebrities claim to speak for others provides an opportunity to address this. In this thesis I argue successful exchange is contingent on acceptance of such claims, and contribute an original model for understanding this process. I explore the implicit interconnections between Saward’s (2010) theory of representative claims, and Bourdieu’s (1991) work on political capital and the political field. On this basis, I argue celebrity capital has greater explanatory power in political contexts when fused with Saward’s theory of representative claims. Three qualitative case studies provide demonstrations of this process at work. Contributing to work on how celebrities are evaluated within political and cultural hierarchies (Inthorn and Street, 2011; Marshall, 2014; Mendick et al., 2018; Ribke, 2015; Skeggs and Wood, 2011), I ask which key factors influence this process. -

1 the Chilcot Report Some Thoughts on International Law And

The Chilcot Report Some Thoughts on International Law and Legal Advice James A Green and Stephen Samuel+ Abstract The Report of the Iraq (Chilcot) Inquiry was finally published, 7 years after the Inquiry’s creation, on 6 July 2016. The scope of the Inquiry’s work was vast, and this was reflected in the enormous size of its final Report. The publication of the Report thus raises a multitude of questions requiring further analysis. In this short article, we aim to contribute some initial thoughts, immediately following the Report’s publication, in just two (interrelated) areas. First, we comment on the role of international law in the Chilcot Inquiry. To what extent was international law considered and how was it presented in the Report? We also ask whether the Report reaches any implicit substantive legal conclusions, despite formally refraining from determinations of law. Secondly, we review the Inquiry’s findings concerning international legal advice and legal advisers. In particular, we contribute some thoughts on the Report’s treatment of questions relating to the appropriate recipients of legal advice and its transparency, the timeliness of advice, the perception and treatment of law and legal advice by the Government, and the independence and quality of that advice. Professor of Public International Law, University of Reading. + Doctoral Candidate, University of Reading. The authors would like to thank April Longstaffe for her research assistance and the ESRC funded ‘Commissions of Inquiry: Problems and Prospects’ project based at the Human Rights and International Law Unit, University of Liverpool, for the financial support both in relation to financing April’s work for us and for funding our trip to Liverpool in January 2015 (well before the publication of the Chilcot Report in July 2016) to present a work-in-progress version of our underpinning research. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Open PDF 132KB

Written evidence from Dr Samantha Newbery (CHIS0009) Biography A researcher specialising in intelligence and counter-terrorism, Dr Newbery’s forthcoming book addresses the intersection of the use of informers (also known as agents and covert human intelligence sources (CHIS)) and criminality during ‘the troubles’ in Northern Ireland. The book’s themes and cases are directly relevant to this Bill. Dr Newbery’s previous research also addressed policy-making on human rights issues. Her book Interrogation, Intelligence and Security (Manchester University Press, 2015) considered legal and ethical questions raised by the UK’s use of controversial interrogation techniques for counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency since 1945, techniques that were found to be in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights. She is also co-author of Why Spy? The Art of Intelligence (Hurst, 2015) with the late Brian Stewart CMG, a former Deputy Chief of the Secret Intelligence Service. Executive Summary 1. A statutory power to authorise criminal conduct by CHIS This written evidence is in favour of efforts to establish a statutory power to authorise criminal conduct by CHIS. It is appropriate that the Bill covers all public authorities that RIPA permits to use CHIS. Authorisations should only be granted after being approved by an independent review. 2. Immunity from prosecution The ability to prosecute current and former CHIS is essential. The fact that the Bill does not grant them immunity from prosecution should be made clearer to the public, to CHIS and to the handlers to whom CHIS report, either in the Bill itself or through associated publicity. -

Commonwealth Lawyers Association Amicus

Nos. 15-1358, 15-1359, and 15-1363 In the Supreme Court of the United States JAMES W. ZIGLAR, Petitioner, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. On Writs Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Second Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE COMMONWEALTH LAWYERS ASSOCIATION IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS GARY A. ISAAC Counsel of Record LOGAN A. STEINER JED W. GLICKSTEIN Mayer Brown LLP 71 S. Wacker Dr. Chicago, IL 60606 [email protected] (312) 782-0600 Counsel for Amicus Curiae (Additional Captions Listed on Inside Cover) JOHN D. ASHCROFT, ET AL., Petitioners, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. DENNIS HASTY, ET AL., Petitioners, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...................................... ii INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE...................1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT...........................2 ARGUMENT ..............................................................4 I. The Court Should Consider The Prac- tices Of Other Western Democracies And The European Court Of Human Rights In Deciding Whether To Recog- nize A Bivens Remedy .....................................4 II. Barring Any Remedy In This Case Would Be At Odds With Foreign Deci- sions And Practice ...........................................8 A. Other Nations Provide Monetary Remedies For Human-Rights Abuses In Alleged Terrorism- Related Cases........................................9 B. The European Court Of Human Rights Likewise Provides Mone- tary Remedies For Human Rights Violations In Cases Implicating National Security................................15 C. Other Western Democracies And The European Court Of Human Rights Recognize Damages Ac- tions Even Where National Secu- rity Is Implicated ................................19 CONCLUSION .........................................................20 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Agiza v. Sweden, Commc’n No. -

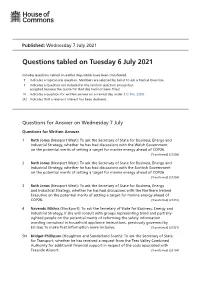

Questions Tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021

Published: Wednesday 7 July 2021 Questions tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 7 July Questions for Written Answer 1 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Welsh Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27308) 2 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Scottish Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27309) 3 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Northern Ireland Executive on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27310) 4 Navendu Mishra (Stockport): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, if she will consult with groups representing blind and partially- sighted people on the potential merits of reforming the safety information wording contained in household appliance instructions, previously governed by EU law, to make that information more inclusive. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

Government Turns the Other Way As Judges Make Findings About Torture and Other Abuse

USA SEE NO EVIL GOVERNMENT TURNS THE OTHER WAY AS JUDGES MAKE FINDINGS ABOUT TORTURE AND OTHER ABUSE Amnesty International Publications First published in February 2011 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2011 Index: AMR 51/005/2011 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 Judges point to human rights violations, executive turns away ........................................... 4 Absence -

Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, and FUTURE by Andrew Watkins

PEACEWORKS Taliban Fragmentation FACT, FICTION, AND FUTURE By Andrew Watkins NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 Making Peace Possible NO. 160 | MARCH 2020 ABOUT THE REPORT This report examines the phenomenon of insurgent fragmentation within Afghanistan’s Tali- ban and implications for the Afghan peace process. This study, which the author undertook PEACE PROCESSES as an independent researcher supported by the Asia Center at the US Institute of Peace, is based on a survey of the academic literature on insurgency, civil war, and negotiated peace, as well as on interviews the author conducted in Afghanistan in 2019 and 2020. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Andrew Watkins has worked in more than ten provinces of Afghanistan, most recently as a political affairs officer with the United Nations. He has also worked as an indepen- dent researcher, a conflict analyst and adviser to the humanitarian community, and a liaison based with Afghan security forces. Cover photo: A soldier walks among a group of alleged Taliban fighters at a National Directorate of Security facility in Faizabad in September 2019. The status of prisoners will be a critical issue in future negotiations with the Taliban. (Photo by Jim Huylebroek/New York Times) The views expressed in this report are those of the author alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. An online edition of this and related reports can be found on our website (www.usip.org), together with additional information on the subject. © 2020 by the United States Institute of Peace United States Institute of Peace 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. -

The Labour Party Is More Than the Shadow Cabinet, and Corbyn Must Learn to Engage with It

The Labour Party is more than the shadow cabinet, and Corbyn must learn to engage with it blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/the-labour-party-is-more-than-the-shadow-cabinet/ 1/11/2016 The three-day reshuffle of the shadow cabinet might have helped Jeremy Corbyn stamp his mark on the party but he needs to do more to ensure his leadership lasts, writes Eunice Goes. She explains the Labour leader must engage with all groups that have historically made up the party, while his rhetoric should focus more on policies that resonate with the public. Doing so will require a stronger vision of what he means by ‘new politics’ and, crucially, a better communications strategy. By Westminster standards Labour’s shadow cabinet reshuffle was ‘shambolic’ and had the key ingredients of a ‘pantomime’. At least, it was in those terms that it was described by a large number of Labour politicians and Westminster watchers. It certainly wasn’t slick, or edifying. Taking the best of a week to complete a modest shadow cabinet reshuffle was revealing of the limited authority the leader Jeremy Corbyn has over the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP). Against the wishes of the Labour leader, the Shadow Foreign Secretary Hilary Benn and the Shadow Chief Whip Rosie Winterton kept their posts. However, Corbyn was able to assert his authority in other ways. He moved the pro-Trident Maria Eagle from Defence and appointed the anti-Trident Emily Thornberry to the post. He also imposed some ground rules on Hillary Benn and got rid of Michael Dugher and Pat McFadden on the grounds of disloyalty. -

Annual Report 2001: the Government's Expenditure Plans For

Annual Report 2001 The Government’s Expenditure Plans 2001–02 to 2003–04 Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions Office of the Rail Regulator Office of Water Services Ordnance Survey Presented to Parliament by the Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary of State for the Environment, Transport and the Regions, and the Chief Secretary to the Treasury by command of Her Majesty March 2001 Cm 5105 £30.00 Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone 020 7944 3000 Internet service www.detr.gov.uk Acknowledgements Cover and inside: Yellow cleaner – Association of Town Centre Management. Cover and Inside: House and children – Rural Housing Trust and Colchester Borough Council. Inside: Landscape – South Downs Conservation Board. © Crown Copyright 2001 Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with the Crown. This publication (excluding the Royal Arms and logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or media without requiring specific permission. This is subject to the material not being used in a derogatory manner or in a misleading context. The source of the material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document must be included when being reproduced as part of another publication or service. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to HMSO, The Copyright Unit, St Clements House, 2–16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to The Copyright Unit, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, St Clements House, 2–16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. -

Scotland: Toward a New Settlement? in This Issue

| THE CONSTITUTION UNIT NEWSLETTER | ISSUE 38 | JANUARY 2008 | MONITOR SCOTLAND: TOWARD A NEW SETTLEMENT? IN THIS ISSUE The constitutional debate in Scotland in the SNP White Paper) with ideas on reconciling continues apace. In the last Monitor we more devolution with a renewal of the UK BRITISH BILL OF RIGHTS 2 reported on the SNP Government’s White union (which mark out a very different agenda). Paper Choosing Scotland’s Future – Especially notable were her ideas on risk-sharing A National Conversation. This set out options through fiscal solidarity across the UK, and those for Scotland’s constitutional future, ranging on guaranteeing rights of ‘social citizenship’ PARTY FUNDING REFORM 2 from further-reaching devolution to the SNP’s across the UK. Emphasising social rights across own preference of independence. jurisdictions suggests a concern to build common purposes – or, put another way, limits to policy EU REFORM TREATY 3 Beyond their commitment to ignore the SNP’s variation – to which risk-sharing and solidarity can ‘national conversation’, the other main parties be put to work in a UK-wide framework. in Scotland were generally silent on Scotland’s PARLIAMENT 3 constitutional options until a speech by the new This is a bold agenda. For it to work much would Labour leader in Scotland, Wendy Alexander, at depend on a willingness in Westminster and the University of Edinburgh on St Andrew’s Day, Whitehall to think creatively about rebalancing DEVOLUTION 5 30 November. This set out a unionist perspective the union. If devolution is to have a stronger on constitutional change; unlike the SNP White UK-wide context, then the devolved institutions Paper, independence was not an option.