A Logical Illuminatioi\I of the Advaita Theory of Perception : Some Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advaita, Vishistadvaita and Dvaita

FAQ Advaita, Vishistadvaita and Dvaita 1. How did the three systems of Vedanta philosophy, namely Advaita, Vishistadvaita and Dvaita come about? 2. What is the Bheda sruti? 3. What are the passages in the Vedas which come under the category of bheda sruti? 4. What is Abheda sruti? 5. What are the passages in the veda that describe the Abhedasruti? 6. What is Ghataka sruti? 7. Name the passages from the Vedas, which are in the nature of Ghataka sruti? 8. Why is this called Antaryami Brahmana? 9. Why are the above passages of the Vedas called ghataka sruti? 10. How do we then interpret the abheda sruti? 11. Explain a little more on Abheda Sruti? 12. So, what is the final conclusion on Abheda Sruthi? 13. What is the meaning of the word "Advaita"? 14. What is the meaning of the word "Visishtadvaita"? 15. What is the meaning of the word" Dvaita"? 16. How do the Advaitins explain the various passages in the Vedas, which do not support their philosophy? In other words, how do they explain the bheda srutis which say that Jivatma and Paramatma are different? 17. How do Vishistadvaitin's rebut the argument of Advaitins that abheda srutis supersede the bheda srutis? 18. How do the Dvaitins explain the abheda srutis, which are against their philosophy - that Jivatma and Paramatma are eternally different? 19. What is Vishistadvaitins answer to this argument? 20. So, what is the speciality of Visishtadvaita vis-a-vis Advaita and Dvaita? 21. What does the term 'maya' mean? 22. But certainly, one is seeing the world; and one sees the various things in the world, with our eyes. -

He Hindu View of Life Accords Great Importance to the Mind Since Both

ind Accordin to Hindu Philoso hical stems SWAMI HARSHANANDA he Hindu view of life accords great The Nyaya-Vaisheshika schools consider importance to the mind since both the manas or the mind as one of the dravyas abhyudaya (worldly prosperity) and (fundamental or basic realities) out of which nihshreyasa (spiritual progress) depend upon the world is eventually created. It acts as a the condition of the mind. An impure mind link between the soul and the sense-organs binds the soul to transmigratory existence by which the external objects are known. whereas a pure mind leads to moksha or Certain cults of Shaivism and Shaktaism liberation.! (Tantras) advocate the theory that mind is a While recognizing the importance limitation or a modification of pure conscious of the mind as a distinguishing unique fea ness. ture of human beings, the Hindu scriptures As regards the size of the mind, some and the various systems of Hindu philoso systems like Nyaya and Vaisheshika hold phy have given different views about its it as anu (atomic) while others (Advaita content, nature and function. A study of the Vedanta) consider it as Vibhu (all-pervading). mind, therefore, will not only be interesting Importance of the Mind but also useful in one's personal life of spiri tual evolution. The ultimate purpose of human life is to attain moksha or liberation from transmi What the Mind Is gratory existence. This is possible only when The Chhandogya Upanishad2 declared sadhana or spiritual practice is undertaken that the mind is 'annamaya', made up of the as per the dictates of the scriptures. -

Dvaita Vs. Advaita

> Subject: dvaita vs advaita > I have a very basic question to this very learned group. could someone please > tell us what exactly does dvaita and advaitha mean. kanaka One of the central questions concerning Vedanta philosophers is the relationship of the individual self to the Absolute or Supreme Self. The sole purpose for this question is to determine the nature of contemplative meditation and to determine whether moksha, the state of release, is something worth seeking. The Dvaita school, inaugurated by Madhvacharya (Ananda Tirtha), argues that there is an inherent and absolute five-fold difference in Reality -- between one soul and another, between the soul and God, between God and matter, between the soul and matter, and between matter and matter. These differences are not only individuations, but also inherent qualitative differences, i.e., in its essentially pure state, one individual self is _not_ equal to another in status, but only in genus. Therefore, there are inherently female jIvas, inherently male jIvas, brahmin jIvas, non-brahmin jIvas, and this differentiation exists even in liberation. Consequently, any sort of unity, whether it be mystical or ontological, between the individual self and God is impossible in Dvaita. Hence the term ``Dvaita'' or ``dualism''. Liberation consists of experiencing one's essential nature in parama padam as a reflection of God's glory. Such liberation is achieved through bhakti or loving devotion. The Advaita school, represented in its classical and most powerful form by Sankaracharya, argues that only the Absolute Self exists, _and_ all else is false. The universe and our existence as individuals is not _unreal_, mind you, but a false imposition on a real substrate, the non-dual, undifferentiated principle of consciousness. -

P R S F a C S in the Present Study of Th.8 Mandukya Karika Of

P R S F A C S In the present study of th.8 Mandukya karika of • • Gaudapada I have tried to present the bare philosophical argument which is at the back of Gaudapada karikas. I find several v;ords such as Deva, Turya, Prana, Vibhu, PrajrTa, Taijasa, Yisva, Ananda, etc., usedj. 'These xv’ords have been usually interpreted by the scholars in some religious or m*ystical way. Thus, for example, when one finds the interpretation of a karika where it has been said that the Prajna is in the 'deep sleep' , one begins to v/onder as to v.^hat this 'mystical' 'deep sleep' is. When one finds the translation of v/ords like Deva as W»- the Lord, or^Divine and of Yibhu as omnipresent etc., one begins to think that Gaudapada karikas are religious in content. The present study attempts to give a ncjn- -------- ry 1igious and secular interpretation of Gaudapada’s text. In some interpretations I also find such proyieras as that of ITpasana, attainment of t'n.e highest reality etc. In the present study I have not posed these problems. I am interested primari].y in the r^hilosophical arguments and I thought that such references may not be necessary for our studies. I am* also not interestel in comparing Gaudapada's philosophy with certain other oriental or occidental doctrines. Such a study could be a toDic for another indeoendent work. It is indeed 11 useful to have such a comparative picture of the development of certain thought and ideas. Still when we are conca,rned with a particular text of a philosopher our Investigations pet naturally confined to the text primarily. -

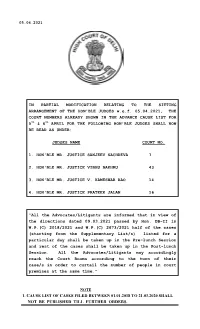

1. Cause List of Cases Filed Between 01.01.2018 to 21.03.2020 Shall Not Be Published Till Further Orders

05.04.2021 IN PARTIAL MODIFICATION RELATING TO THE SITTING ARRANGEMENT OF THE HON'BLE JUDGES w.e.f. 05.04.2021, THE COURT NUMBERS ALREADY SHOWN IN THE ADVANCE CAUSE LIST FOR 5th & 6th APRIL FOR THE FOLLOWING HON'BLE JUDGES SHALL NOW BE READ AS UNDER: JUDGES NAME COURT NO. 1. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJEEV SACHDEVA 7 2. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE VIBHU BAKHRU 43 3. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE V. KAMESWAR RAO 14 4. HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PRATEEK JALAN 16 “All the Advocates/Litigants are informed that in view of the directions dated 09.03.2021 passed by Hon. DB-II in W.P.(C) 2018/2021 and W.P.(C) 2673/2021 half of the cases (starting from the Supplementary List/s) listed for a particular day shall be taken up in the Pre-lunch Session and rest of the cases shall be taken up in the Post-lunch Session. All the Advocates/Litigants may accordingly reach the Court Rooms according to the turn of their case/s in order to curtail the number of people in court premises at the same time.” NOTE 1. CAUSE LIST OF CASES FILED BETWEEN 01.01.2018 TO 21.03.2020 SHALL NOT BE PUBLISHED TILL FURTHER ORDERS. HIGH COURT OF DELHI: NEW DELHI No. 384/RG/DHC/2020 DATED: 19.3.2021 OFFICE ORDER HON'BLE ADMINISTRATIVE AND GENERAL SUPERVISION COMMITTEE IN ITS MEETING HELD ON 19.03.2021 HAS BEEN PLEASED TO RESOLVE THAT HENCEFORTH THIS COURT SHALL PERMIT HYBRID/VIDEO CONFERENCE HEARING WHERE A REQUEST TO THIS EFFECT IS MADE BY ANY OF THE PARTIES AND/OR THEIR COUNSEL. -

What the Upanisads Teach

What the Upanisads Teach by Suhotra Swami Part One The Muktikopanisad lists the names of 108 Upanisads (see Cd Adi 7. 108p). Of these, Srila Prabhupada states that 11 are considered to be the topmost: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, Brhadaranyaka and Svetasvatara . For the first 10 of these 11, Sankaracarya and Madhvacarya wrote commentaries. Besides these commentaries, in their bhasyas on Vedanta-sutra they have cited passages from Svetasvatara Upanisad , as well as Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads. Ramanujacarya commented on the important passages of 9 of the first 10 Upanisads. Because the first 10 received special attention from the 3 great bhasyakaras , they are called Dasopanisad . Along with the 11 listed as topmost by Srila Prabhupada, 3 which Sankara and Madhva quoted in their sutra-bhasyas -- Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads --are considered more important than the remaining 97 Upanisads. That is because these 14 Upanisads are directly referred to by Srila Vyasadeva himself in Vedanta-sutra . Thus the 14 Upanisads of Vedanta are: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Aitareya, Taittiriya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Svetasvatara, Kausitaki, Subala and Mahanarayana. These 14 belong to various portions of the 4 Vedas-- Rg, Yajus, Sama and Atharva. Of the 14, 8 ( Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittrirya, Mundaka, Katha, Aitareya, Prasna and Svetasvatara ) are employed by Vyasa in sutras that are considered especially important. In the Gaudiya Vaisnava sampradaya , Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana shines as an acarya of vedanta-darsana. Other great Gaudiya acaryas were not met with the need to demonstrate the link between Mahaprabhu's siksa and the Upanisads and Vedanta-sutra. -

Rukmini Haran

Rukmini Haran Venue: Amravati, Nov 2003 Srimad Bhagvatam chapters 52 and 53 and in the middle of chapter 52 there is pastime kidnapping of Rukmini. Rajo vaca King Pariksit was very inquisitive to know, Sukhdev Goswami has made brief mention of “vaidarbhim bhismaka-sutam” (S.B 10.52.16) Rukmini is daughter of King Bhismaka and as soon as topic of her marriage came King Pariksit became inquires to know please tell me more! “rucirananam” Rukmini very sweet faced “rucirananam”. “krsnasyamita-tejasah bhagvan srorum icchami” (S.B 10.52.18) then the unlimited prowess of the Lord. Sukhdev Gosami begins narration “rajasid bhismako nama” so then once upon a time there was a King Bhismaka he was ruling state of kingdom called “vidarbhadhupatir mahantasya pancabhavan putrah” he had 5 sons “kanyaika ca varanana” (S.B 10.52.21). He had one very beautiful daughter, 5 brothers of Rukmini have been mentioned. Introduction to Rukmini “sopasrutya mukundasya rupa-virya-guna-sriyah” (S.B 10.52.23). Rukmini she used to hear about rupa– form, beauty, virya, guna-qualities of Mukunda and result was “mene sadrsam patim” (S.B 10.52.23). I would like to have person like him as my husband. And then Krishna also had been hearing in Dwaraka about the intelligent Rukmini, the audarya – charitable, magnanimous personality of Rukmini, her beauty and her character and in Dwaraka Krishna also had made up his mind. I ever get wife I would like wife like this, the description that I had been hearing about Rukmini. So both of them were all set mind was set, mind was fixed. -

The Essence of the Samkhya II Megumu Honda

The Essence of the Samkhya II Megumu Honda (THE THIRD CHAPTER) (The opponent questions;) Now what are the primordial Matter and others, from which the soul should be discriminated? (The author) replies; They are the primordial Matter (prakrti), the Intellect (buddhi), the Ego- tizing organ (ahankara), the subtle Elements (tanmatra), the eleven sense organs (indriya) and the gross Elements (bhuta) in sum just 24." The quality (guna), the action (karman) and the generality (samanya) are included in them because a property and one who has property are iden- tical (dharma-dharmy-abhedena). Here to be the primordial Matter means di- rectly (or) indirectly to be the material cause (upadanatva) of all the mo- dification (vikara), because its chief work (prakrsta krtih) is formed of tra- nsf ormation (parinama), -thus is the etymology (of prakrti). The primordial Matter (prakrti), the Capacity (sakti), the Unborn (aja), the Principal (pra- dhana), the Unevolved (avyakta), the Dark (tamers), the Illusion (maya), the Ignorance (avidya) and so on are the synonyms') of the primordial Matter. For the traditional scripture says; "Brahmi (the Speech) means the science (vidya) and the Ignorace (avidya) means illusion (maya) -said the other. (It is) the primordial Matter and the Highest told the great sages2)." And here the satt va and other three substances are implied (upalaksita) as. the state of equipoise (samyavastha)3). (The mention is) limitted to implication 1) brahma avyakta bahudhatmakam mayeti paryayah (Math. ad SK. 22), prakrtih pradhanam brahma avyaktam bahudhanakammayeti paryayah (Gaudap. ad SK. 22), 自 性 者 或 名 勝 因 或 名 爲 梵 或 名 衆 持(金 七 十 論ad. -

Dvaita Vedanta

Dvaita Vedanta Madhva’s Vaisnava Theism K R Paramahamsa Table of Contents Dvaita System Of Vedanta ................................................ 1 Cognition ............................................................................ 5 Introduction..................................................................... 5 Pratyaksa, Sense Perception .......................................... 6 Anumana, Inference ....................................................... 9 Sabda, Word Testimony ............................................... 10 Metaphysical Categories ................................................ 13 General ........................................................................ 13 Nature .......................................................................... 14 Individual Soul (Jiva) ..................................................... 17 God .............................................................................. 21 Purusartha, Human Goal ................................................ 30 Purusartha .................................................................... 30 Sadhana, Means of Attainment ..................................... 32 Evolution of Dvaita Thought .......................................... 37 Madhva Hagiology .......................................................... 42 Works of Madhva-Sarvamula ......................................... 44 An Outline .................................................................... 44 Gitabhashya ................................................................ -

Secrets of Srimad Bhagavad Gita Revealed

Secrets of Srimad Bhagavad Gita Revealed By Manga Viswanadha Rao Introduction The Bhagavad Gita, the greatest devotional book of Hinduism, has long been recognized as one of the world‘s spiritual classics and a guide to all on the path of Truth. The land of the Vedas and the Upanishads – that is India. India has a rich culture of respecting the Father, Mother, Elders and Teachers. The influence of Western Culture and the glitz of Materialism is misleading the children of India and corrupting the society by compromising the values. This is an attempt to lead the people in the right direction. Let us read the mantra from Yajur Veda (36-24) and understand the deep meaning and spiritual significance it upholds. Let us live long. Without depending on anyone. I am deeply pained by the children over speeding for the thrill on the streets of India. The immaturity of some children is evident with their utter disregard to their self well-being when they forget that ―Speed Thrills, But also Kills‖. Some other children want to depend their entire lives on the hard work of their parents. Let us take Vedas as an example of how we need to live our lives. Let us make a firm resolve to lead Young India by example with the inspiration of Swami Vivekananda. Let us make a firm resolve to lead the Future generations of Young India with the inspiration provided by the teachings of Lord Krishna in Bhagavad Gita. Let us learn to take good care of ourselves. TACHCHA KSHURDEVHITAM PURASTACHRUKRAMMUCHARAT PASHYEM SHARADAHA SHATAM JIVEMA SHRADAHA SHATAM SHRUNUYAMA SHARADAHA SHATAM PRA BRAYAMA SHARADAHA SHATMADINAHA SYAM SHARADAHA SHATAM BHUYASHCHA SHARADAHA SHATAM BHUYASHCHA SHARADAHA SHATATA -------------(36/24, Yajurveda) He first arose who was the doer of good to the scholars and was blessed with pure eyes of knowledge. -

The Vedanta-Kaustubha-Prabha of Kesavakasmtribhajta : a Critical Study

THE VEDANTA-KAUSTUBHA-PRABHA OF KESAVAKASMTRIBHAJTA : A CRITICAL STUDY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF D. LITT. TO ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY. ALIGARH 1987 BY DR. MAOAN MOHAN AGRAWAL M.A., Ph. D. Reader in Sanskrit, University of Delhi T4201 T420 1 THE VEDANTA-KAUSTUBHA-PRAT^HA OF KESAVAKASMIRIBHATTA : * • A CRITICAL STUDY _P _F^_E_F_A_C_E_ IVie Nimbarka school of Vedanta has not so far been fully explored by modern scholars. There are only a couple of significant studies on Nimbarka, published about 50 years ago. The main reason for not ransacking this system seems to be the non availability of the basic texts. The followers of this school did not give much importance to the publications and mostly remained absorbed in the sastric analysis of the Ultimate Reality and its realization. One question still remains unanswered as to why there is no reference to Sankarabhasya in Nimbarka's commentary on the Brahma-sutras entitled '"IVie Vedanta-pari jata-saurabha", and why Nimbarka has not refuted the views of his opponents, as the other Vaisnava Acaryas such as R"amanuja, Vallabha, ^rikara, Srikantha and Baladeva Vidyabhusana have done. A comprehensive study of the Nimbarka school of Vedanta is still a longlelt desideratum. Even today the basic texts of this school are not available to scholars and whatsoever are available, they are in corrupt form and the editions are full of mistakes. (ii) On account of the lack of academic interest on the part of the followers of this school, no critical edition of any Sanskrit text has so far been prepared. Therefore, the critical editions of some of the important Sanskrit texts viz. -

Philosophy of Sri Madhvacarya

PHILOSOPHY OF SRI MADHVAGARYA by Vidyabhusana Dr. B. N. K. SHARMA, m. a., Ph. d., Head of the Department of Sanskrit and Ardhamagadhl, Ruparel College, Bombay- 16. 1962 BHARATIYA VIDYA BHAVAN BOMBAY-7 Copyright and rights of translation and reproduction reserved by the author.. First published.' March, 1962 Pri/e Rs. 15/- Prlnted in India By h. G. Gore at the Perfecta Printing Works, 109A, Industrial Aiea, Sion, Bombay 22. and published by S. Ramakrishnan, Executive Secrelaiy Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bombay 1. Dedicated to &R1 MADHVACARYA Who showed how Philosophy could fulfil its purpose and attain its goal by enabling man to realize the eternal and indissoluble bond of Bitnbapratibimbabhava that exists between the Infinite and the finite. ABBREVIATIONS AV. Anu-Vyakhyana Bhag. Bhagavata B. T. Bhagavata-Tatparya B. S. Brahma-Sutra B. S. B. Brahmasutra Bhasya Brh. Up. Brhadaranyaka-Upanisad C. Commentary Chan. Up. Chandogya Upanisad Cri. Sur. I. Phil. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy D. M. S. Daivi Mimamsa Sutras I. Phil. Indian Philosophy G. B. Glta-Bha»sya G. T. Glta-Tatparya KN. Karma-Nirnaya KN. t. Karma Nirpaya Tika M. G. B. Madhva's GTta Bhasya M. Vij. Madhvavijaya M. S. Madhvasiddhantasara Mbh. Mahabharata Mbh. T. N. Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya Man. Up. Mandukya Upanisad Mith. Kh.t. Mithyatvanumana Khandana Tika Mund.Up. Mundaka Upanisad Nym- Nyayamrta NS. Nyaya Sudha NV. Nyaya Vivarapa PP- Pramana Paddhati P- M. S. Purva Mlmamsa Sutras R- V. Rg Veda R.G.B. Ramanuja's Glta Bhasya S. N. R. Sannyaya Ratnavalf Svet. Up. Svetaivatara Upanisad Tg. ( Nyayamrta )-Tarangini TS.