Domestic Violence and Its Effects on Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Dimensions of the Battered Woman Syndrome

OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL Volume 53, Number 2, 1992 Constitutional Dimensions of the Battered Woman Syndrome ERICH D. ANDERSEN* AND ANNE READ-ANDERSEN** The exclusion of expert witness testimony on the battered woman syndrome ("syndrome") m a criminal trial often raises both evidentiary and constitutional issues for appeal.' Defendants typically offer testimony on the syndrome to prove that they acted m self-defense when they killed or wounded their mates.2 If the trial court excludes the testimony for lack of foundation or because it is irrelevant, for instance, this exclusion creates a potential evidentiary issue for appeal. 3 The same ruling may also raise a constitutional question because the accused has a constitutional right to present a defense.4 The right to present a defense is implicated when the trial court excludes evidence that is favorable and material to the defense.5 Scholars have been attentive to the evidentiary problems associated with excluding testimony on the syndrome. Over the past decade, many commentators have considered whether, and if so when, expert testimony should be admitted to support a battered woman's assertion of self-defense.6 * Associate, Davis Wright Tremame, Seattle, Washington; B.A. 1986, J.D., 1989, Umversity of California, Los Angeles. **Associate, Preston, Thorgrmson, Shidler, Gates & Ellis, Seattle, Washington; B.A. 1986, College of the Holy Cross; J.D., 1989, Umversity of Michigan. This Article is dedicated to our parents: Margaret and David Read and Lotte and David Andersen. Without their love and guidance, this Article would not have been possible. We also thank Joseph Kearney and John Mamer for their valuable editing help. -

Sexist Myths Emergency Healthcare Professionals and Factors Associated with the Detection of Intimate Partner Violence in Women

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Sexist Myths Emergency Healthcare Professionals and Factors Associated with the Detection of Intimate Partner Violence in Women Encarnación Martínez-García 1,2 , Verónica Montiel-Mesa 3, Belén Esteban-Vilchez 4, Beatriz Bracero-Alemany 5, Adelina Martín-Salvador 6,* , María Gázquez-López 7, María Ángeles Pérez-Morente 8,* and María Adelaida Alvarez-Serrano 7 1 Guadix High Resolution Hospital, 18500 Granada, Spain; [email protected] 2 Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Granada, 18016 Granada, Spain 3 Virgen de las Nieves University Hospital, Andalusian Health Service, 18014 Granada, Spain; [email protected] 4 San Cecilio Clinical Hospital, Andalusian Health Service, 18016 Granada, Spain; [email protected] 5 The Inmaculate Clinic, Andalusian Health Service, 18004 Granada, Spain; [email protected] 6 Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Granada, 52005 Melilla, Spain 7 Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Granada, 51001 Ceuta, Spain; Citation: Martínez-García, E.; [email protected] (M.G.-L.); [email protected] (M.A.A.-S.) 8 Montiel-Mesa, V.; Esteban-Vilchez, B.; Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Jaén, 23071 Jaén, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.M.-S.); [email protected] (M.Á.P.-M.) Bracero-Alemany, B.; Martín- Salvador, A.; Gázquez-López, M.; Pérez-Morente, M.Á.; Alvarez- Abstract: This study analysed the capacity of emergency physicians and nurses working in the Serrano, M.A. Sexist Myths city of Granada (Spain) to respond to intimate partner violence (IPV) against women, and the Emergency Healthcare Professionals mediating role of certain factors and opinions towards certain sexist myths in the detection of and Factors Associated with the cases. -

Cycle-Of-Abuse-1-Handout-4-Dragged

HONEYMOON STAGE Relationship starts out with Romance, flowers, lots of compliments and attention says “I love you” early on, comes on strong, quick involvement; after abuse apologizes, makes excuses and all of the above ACUTE BATTERING STAGE Worst abuse, verbal, physical, sexual violence, leaving victim wounded physically, psychologically TENSION BUILDING STAGE Tension builds, arguments, emotional and psychological abuse, criticism, name-calling, threats, intimidation, may be minor physical abuse; victim fearful *Adapted from Lenore Walker’s cycle of violence CYCLE OF ABUSE At the beginning of the relationship, the Honeymoon Stage, the victim is swept off their feet by all the compliments, gifts, and attention. The abuser comes on strong and pressures for a commitment. After awhile, the abuse starts slowly and insidiously, unrecognizable to the victim. And if they do recognize that something might not be right, they make excuses for the abuser’s behavior, as the abuser is quick to apologize and offer explanations that the victim believes. As the victim tolerates the abuse, the abuse escalates slowly and continues through the Tension Building Stage and then the Acute Battering Stage. This is followed by the Honeymoon Stage wherein the abuser apologizes, offers gifts, attention, etc. and once again, the victim, who wants to believe the abuser is capable of change, and/or that they can change him, continues in the relationship. This then becomes a self-perpetuating, vicious, and dangerous cycle. Make no mistake, all the while the abuser is isolating the victim from family and friends by convincing them friends and family no longer care about them or can be trusted. -

A Behavioral Analysis of Intimate Partner Violence Victims

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 4-30-2020 A Behavioral Analysis of Intimate Partner Violence Victims Maryssa Presbitero Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Presbitero, Maryssa, "A Behavioral Analysis of Intimate Partner Violence Victims" (2020). Honors Theses. 3297. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/3297 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: A BEHAVIORAL ANALYTIC VIEW OF INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE VICTIMS 1 A Behavioral Analytic View of Patterns in Intimate Violence Victims Maryssa Presbitero Dr. Angela Moe Dr. Zoann Snyder Dr. Lester Wright Western Michigan University A Behavioral Analytic View of Patterns in Intimate Violence Victims 2 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………….…………. 4 Introduction …………………………………………………………………....…… 5 Scope of the Problem ………………………………………………………. 5 Theory ……………………………………………………………………………… 6 Analyzing Behavior ………………………………………………………… 6 Operant Conditioning ………………………………………………….……. 7 Respondent Conditioning …………………………………………….……... 9 Literature Review ………………………………………………………………….... 9 Childhood Abuse ……………………………………………………………. 9 Substance -

Restorative Justice and Domestic Violence/Abuse

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE/ ABUSE A report commissioned by HMP Cardiff Funded by The Home Office Crime Reduction Unit for Wales August 2008 Updated April 2010 Marian Liebmann and Lindy Wootton 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 Domestic violence/abuse SECTION 1: MAINSTREAM METHODS OF WORKING WITH DOMESTIC VIOLENCE/ABUSE 5 The Freedom Programme for women The Freedom Programme for men Integrated Domestic Abuse Programme (IDAP) Women’s Safety Worker Role The Prison Service Healthy Relationships Programme Family Man Other programmes Hampton Trust Somerset Change Czech Republic: Special service for crime and domestic violence victims Respect Risk assessment in domestic violence cases Research Conclusion SECTION 2: RESTORATIVE JUSTICE PROJECTS WORKING WITH DOMESTIC VIOLENCE/ABUSE 15 Introduction United Kingdom 16 Plymouth Mediation The Daybreak Dove Project Victim Liaison Units Family Mediation Europe (apart from UK) 20 Austria, Belgium, Finland, Germany, Greece, Romania United States 26 North Carolina Navajo Peacemaking Project Canada 28 Newfoundland and Labrador Hollow Water, Lake Winnipeg Edmonton, Alberta Winnipeg, Manitoba Australia 30 Circle Court Transcript Restorative and transformative justice pilot: A communitarian model Research project with Aboriginal people and family violence Family Healing Centre New Zealand 32 South Africa The Gambia Jamaica Colombia Thailand CONCLUSION 35 REFERENCES 36 Acknowledgements 2 INTRODUCTION This report has drawn on many sources. The first is the research undertaken by Marian Liebmann for her book Restorative Justice: How It Works, published by Jessica Kingsley in 2007; the bulk of this research was undertaken in 2006. Further information came from participants at the European Forum for Restorative Justice Conference in Verona in April 2008. Finally we searched the internet for further projects (drawing especially on RJ Online), and also included a brief overview of mainstream methods of working with domestic violence/abuse issues. -

Deficiencies of Battered Woman Syndrome and a New Solution to Closing the Gender Gap in Self-Defense Law Meredith C

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Gender Inequality in the Law: Deficiencies of Battered Woman Syndrome and a New Solution to Closing the Gender Gap in Self-Defense Law Meredith C. Doyle Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Doyle, Meredith C., "Gender Inequality in the Law: Deficiencies of Battered Woman Syndrome and a New Solution to Closing the Gender Gap in Self-Defense Law" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 149. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/149 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE GENDER INEQUALITY IN THE LAW: DEFICIENCIES OF BATTERED WOMAN SYNDROME AND A NEW SOLUTION TO CLOSING THE GENDER GAP IN SELF- DEFENSE LAW SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR KENNETH MILLER AND PROFESSOR DANIEL KRAUSS AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY MEREDITH DOYLE FOR SENIOR THESIS SPRING/2011 APRIL 25, 2011 2 Table of Contents I. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 II. Chapter 1: History of Women and the Law: A Husband Shields His Wife From Justice………………………………………………………………….........5 III. Chapter 2: Rape, Manslaughter, and Self-Defense Law Still Subordinate Women……………………………………………………………………………12 IV. Chapter 3: Theory and Origin of Battered Woman Syndrome…………………....17 V. Chapter 4: Flaws in Walker’s Research and Admissibility of BWS Testimony…..22 VI. Chapter 5: Social and Legal Consequences of Battered Woman Syndrome………30 VII. Chapter 6: A Critical Analysis of Alternatives to Battered Woman Syndrome…. 38 VIII. Chapter 7: Pattern of Domestic Abuse and Social Agency Framework as a New Alternative…………………………………………………………………..46 IX. -

Healing Together: Shifting Approaches to End Intimate Partner Violence

Healing Together: Shifting Approaches to End Intimate Partner Violence Healing Together: Shifting Approaches to End Intimate Partner Violence Marc Philpart Sybil Grant Jesús Guzmán with contributions from Jordan Thierry This paper is dedicated to the loving memory of Lorena Thompson (1933–1965), and all those whose lives were taken or harmed by intimate partner violence. Cover photos: Bryan Patrick Interior photos: Tori Hoffman and Bryan Patrick ©2019 PolicyLink. All rights reserved. PolicyLink is a national research and action institute advancing racial and economic equity by Lifting Up What Works®. http://www.policylink.org • Karena Montag, STRONGHOLD Acknowledgments • Lori Nesbitt, Yurok Tribal Court • Krista Niemczyk, California Partnership to End Domestic Violence • Nicolle Perras, Los Angeles County Public Health • Tony Porter, A CALL TO MEN • Maricela Rios-Faust, Human Options • Erin Scott, Family Violence Law Center We are grateful to our philanthropic partners at Blue Shield • Sara Serin-Christ, Oakland Unite of California Foundation for their generous support and • Mauro Sifuentes, San Francisco Unified School District intellectual contributions. Their generosity and the brilliance • Alisha Somji, Prevention Institute of their team including Lucia Corral Peña, Jelissa Parham, • Andrea Welsing, Los Angeles County Public Health and Richard Thomason have contributed mightily to this paper. This paper would not have been possible if not for their We are deeply grateful for the thoughtful discussions with commitment, support, and intellectual prowess. individuals whose contributions greatly enriched our under- standing of the complexity of intimate partner violence and We are deeply appreciative of the California Partnership helped to inform this paper: to End Domestic Violence for all they have done to advance • Ashanti Branch, Ever Forward Club safety and healing for survivors and their families. -

Five Cycles of Emotional Abuse: Codification and Treatment of An

YOU ARE HOLDING 1.5 CEs IN YOUR HAND! How it works: Read this CE program and complete the post-test on page 19 and mail it to the Chapter office with your check. Score 80% or better and NASW will mail you a certificate for 1.5 CEs. It’s that easy! Five Cycles of Emotional Abuse: Codification and Treatment of an Invisible Malignancy By Sarakay Smullens, MSW, LICSW, BCD Dear Colleagues, nal exploring the preponderance of emotional abuse in my own life and in the life of my clients. These recordings led to an identifi ca- I presented my codifi cation of fi ve cycles of emotional abuse, the tion and documentation of fi ve cycles of parental and caretaker be- history of how this codifi cation developed, and various successful haviors that constitute emotional abuse. treatment options at the April 2006 NASW-MA Symposium. The fi ve cycles codifi ed—enmeshment, extreme overprotection In that workshop, I suggested that, in order to avoid burnout so and overindulgence, complete neglect, rage, and rejection/abandon- common in the helping professions, attendees embrace their most ment—were fi rst published in Annals, the journal of the American unsettling and painful life experiences and will themselves to learn Psychotherapy Association, in the Fall of 2002. In differing ways, from them. I strongly believe that this determination and focus both each cycle entraps its victim in replicative or reactionary relation- promotes and enhances the energy to cope in diffi cult and traumat- ships with family members, friends, teachers, employers, profes- ic times and, at the same time, enriches personal and profession- sional colleagues, and partners. -

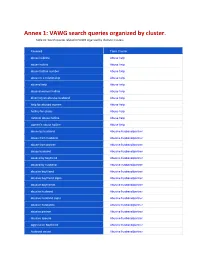

Annex 1: VAWG Search Queries Organized by Cluster

Annex 1: VAWG search queries organized by cluster. Table A1: Search queries related to VAWG organized by thematic clusters. -

Domestic Violence in Low-Income Communities in Mumbai, India Robyn M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Master's Theses University of Connecticut Graduate School 5-6-2015 Domestic Violence in Low-Income Communities in Mumbai, India Robyn M. Jennings [email protected] Recommended Citation Jennings, Robyn M., "Domestic Violence in Low-Income Communities in Mumbai, India" (2015). Master's Theses. 765. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/gs_theses/765 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Connecticut Graduate School at OpenCommons@UConn. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenCommons@UConn. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Domestic Violence in Low-Income Communities in Mumbai, India Robyn Meredith Jennings B.S., Messiah College, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Public Health At the University of Connecticut 2015 i Copyright by Robyn Meredith Jennings 2015 ii APPROVAL PAGE Masters of Public Health Thesis Domestic Violence in Low-Income Communities in Mumbai, India Presented by Robyn Meredith Jennings, B.S. Major Advisor____________________________________________________________ Stephen L. Schensul, Ph.D. Associate Advisor_________________________________________________________ Jane A. Ungemack, Dr.P.H. Associate Advisor_________________________________________________________ Joseph A. Burleson, Ph.D. University of Connecticut 2015 iii Acknowledgements This research paper is made possible with the guidance and direction from Dr. Stephen Schensul Ph.D., who provided advice and expertise on the design of the project, as well as the format and content of the manuscript. I am grateful to Dr. Schensul and those who worked on the RISHTA project for providing the data used in this thesis. -

Intimate Partner Abuse

Domestic Violence: Intimate Partner Abuse Part 1: Domestic Violence Basics This section provides an overview of the definition, scope, and causes of domestic violence, along with the evolving societal responses. The material also provides a description of victims and perpetrators of domestic violence, highlighting prevalent misconceptions, common behaviors, and parenting issues. What is Domestic Violence? Historically, domestic violence has been framed and understood exclusively as a women's issue. Domestic abuse affects women, but it also has devastating consequences for other populations and societal institutions. Men can also be victims of abuse; children are affected by exposure to domestic violence; and formal institutions face enormous challenges responding to domestic violence in their communities. The effects of domestic violence on victims are more typically recognized, but perpetrators also are impacted by their abusive behavior as they stand to lose custody of their children, damage important relationships, and face legal consequences. Domestic violence cuts across every segment of society and occurs in all age, racial, ethnic, socio-economic, sexual orientation, and religious groups. Domestic violence is a social, economic, and health concern that does not discriminate. As a result, communities across the country are developing strategies to stop the violence and provide safe solutions for victims of domestic violence. Defining Domestic Violence Domestic violence, also called intimate partner abuse, intimate partner violence, and domestic abuse, is a "pattern of coercive and assaultive behaviors that include physical, sexual, verbal, and psychological attacks and economic coercion that adults or adolescents use against their intimate partner."1 Domestic violence is not typically a singular event and is not limited only to physical aggression. -

What Is Emotional Abuse?

What Is Emotional Abuse? A comprehensive guide to helping you understand emotional abuse In emotional abuse, an abuser will manipulate a survivor’s feelings in order to control that partner. A survivor may find themselves deep into a relationship before realizing that their choices—everything from who they can talk to, see and where they can go, to whether or not they’re able to end the relationship— are no longer their own; an abusive partner is making them for him or her. It’s a tactic of abuse that is hard to spot and even harder to prove, allowing abusers to get away with it time and time again. This toolkit will provide you with these insights and more. Inside you’ll find: ▪ Helpful Articles ▪ In-Depth Videos ▪ Recommended Books ▪ Survey Results ▪ Lists ▪ Support Communities ▪ Danger Assessments ▪ How to Find Help Introduction There are hundreds of articles on DomesticShelters.org covering the many facets of domestic violence. Here are links to those that will help you answer the question, “What is emotional abuse?” How to Recognize Emotional What Is Emotional Abuse? Abuse A comprehensive guide to 19 questions that help identify this understanding emotional abuse. type of domestic violence. From Romance to Isolation: The Mind-Trip That Is Emotional Understanding Grooming Abuse Anyone can fall for the clever How to recognize the signs of an manipulations of an abusive abuse that leaves no bruises. partner. Helpful Articles What is Coercive Control? More About Coercive Control A Q&A with author, activist and Why women are most likely to be professor Lisa Aronson Fontes, victims of this type of abuse and PhD.