The Effectiveness of Teaching Traditional Grammar on Writing Composition at the High School Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional

Traditional Grammar Review Page 1 of 15 TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR REVIEW I. Parts of Speech Traditional grammar recognizes eight parts of speech: Part of Definition Example Speech noun A noun is the name of a person, place, or thing. John bought the book. verb A verb is a word which expresses action or state of being. Ralph hit the ball hard. Janice is pretty. adjective An adjective describes or modifies a noun. The big, red barn burned down yesterday. adverb An adverb describes or modifies a verb, adjective, or He quickly left the another adverb. room. She fell down hard. pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. She picked someone up today conjunction A conjunction connects words or groups of words. Bob and Jerry are going. Either Sam or I will win. preposition A preposition is a word that introduces a phrase showing a The dog with the relation between the noun or pronoun in the phrase and shaggy coat some other word in the sentence. He went past the gate. He gave the book to her. interjection An interjection is a word that expresses strong feeling. Wow! Gee! Whew! (and other four letter words.) Traditional Grammar Review Page 2 of 15 II. Phrases A phrase is a group of related words that does not contain a subject and a verb in combination. Generally, a phrase is used in the sentence as a single part of speech. In this section we will be concerned with prepositional phrases, gerund phrases, participial phrases, and infinitive phrases. Prepositional Phrases The preposition is a single (usually small) word or a cluster of words that show relationship between the object of the preposition and some other word in the sentence. -

Grammar: a Historical Survey

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 10, Issue 6 (May. - Jun. 2013), PP 60-62 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Grammar: A Historical Survey Dr Pandey Om Prakash Associate Professor, Dept of English, Gaya College, Gaya (Under Magadha University, Bodh Gaya India) The term grammar has been derived from the Greek word ‘grammatica or grammatika techne’ which means ‘the art of writing’. The Greeks considered grammar to be a branch of philosophy concerned with the art of writing. In the middle ages grammar came to be regarded as a set of rules, usually in the form of text book, dictating correct usage. So in the widest and the traditional sense, grammar came to mean a set of normative and prescriptive rules in order to set up a standard of ‘correct usage’. The earliest reference of any grammar is to be found in 600 B.C.. Panini, in 600 B.C., was a Sanskrit grammarian from Pushkalvati, Gandhara, in modern day Charsadda District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Panini is known for his formulation of 3959 rules of Sanskrit morphology, syntax, semantics in the grammar known as Ashtadhyayi meaning eight chapters. After Panin observations on Language are found in the records we have of pre-Socratic philosophers, the fifth century rhetoricians, Plato and Aristotle. The sources of knowledge of the pre-Socratic and the early theoraticians are fragmentary. It would be wise therefore to begin with Plato. The earliest extinct document in Greek on the subject of language is Cratylus, one of Plato’s dialogues. -

Applying the Principle of Simplicity to the Preparation of Effective English Materials for Students in Iranian High Schools

APPLYING THE PRINCIPLE OF SIMPLICITY TO THE PREPARATION OF EFFECTIVE ENGLISH MATERIALS FOR STUDENTS IN IRANIAN HIGH SCHOOLS By MOHAMMAD ALI FARNIA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1980 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Professor Arthur J. Lewis, my advisor and chairperson of my dissertation committee, for his valuable guidance, not only in regard to this project, but during my past two years at the Uni- versity of Florida. I believe that without his help and extraordinary patience this project would never have been completed, I am also grateful to Professor Jayne C. Harder, my co-chairperson, for the invaluable guidance and assistance I received from her. I am greatly indebted to her for her keen and insightful comments, for her humane treatment, and, above all, for the confidence and motivation that she created in me in the course of writing this dissertation. I owe many thanks to the members of my doctoral committee. Pro- fessors Robert Wright, Vincent McGuire, and Eugene A. Todd, for their careful reading of this dissertation and constructive criticism. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to my younger brother Aziz Farnia, whose financial support made my graduate studies in the United States possible. My personal appreciation goes to Miss Sofia Kohli ("Superfish") for typing the final version of this dissertation. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS , LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ^ ABSTRACT ^ii CHAPTER I I INTRODUCTION The Problem Statement 3 The Need for the Study 4 Problems of Iranian Students 7 Definition of Terms 11 Delimitations of the Study 17 Organization of the Dissertation 17 II REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 19 Learning Theories 19 Innateness Universal s in Language and Language Learning .. -

4. the History of Linguistics : the Handbook of Linguistics : Blackwell Reference On

4. The History of Linguistics : The Handbook of Linguistics : Blackwell Reference On... Sayfa 1 / 17 4. The History of Linguistics LYLE CAMPBELL Subject History, Linguistics DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405102520.2002.00006.x 1 Introduction Many “histories” of linguistics have been written over the last two hundred years, and since the 1970s linguistic historiography has become a specialized subfield, with conferences, professional organizations, and journals of its own. Works on the history of linguistics often had such goals as defending a particular school of thought, promoting nationalism in various countries, or focussing on a particular topic or subfield, for example on the history of phonetics. Histories of linguistics often copied from one another, uncritically repeating popular but inaccurate interpretations; they also tended to see the history of linguistics as continuous and cumulative, though more recently some scholars have stressed the discontinuities. Also, the history of linguistics has had to deal with the vastness of the subject matter. Early developments in linguistics were considered part of philosophy, rhetoric, logic, psychology, biology, pedagogy, poetics, and religion, making it difficult to separate the history of linguistics from intellectual history in general, and, as a consequence, work in the history of linguistics has contributed also to the general history of ideas. Still, scholars have often interpreted the past based on modern linguistic thought, distorting how matters were seen in their own time. It is not possible to understand developments in linguistics without taking into account their historical and cultural contexts. In this chapter I attempt to present an overview of the major developments in the history of linguistics, avoiding these difficulties as far as possible. -

A Short History of Morphological Theory∗

A short History of Morphological Theory∗ Stephen R. Anderson Dept. of Linguistics, Yale University Interest in the nature of language has included attention to the nature and structure of words — what we call Morphology — at least since the studies of the ancient Indian, Greek and Arab grammarians, and so any history of the subject that attempted to cover its entire scope could hardly be a short one. Nonetheless, any history has to start somewhere, and in tracing the views most relevant to the state of morphological theory today, we can usefully start with the views of Saussure. No, not that Saussure, not the generally acknowledged progenitor of modern linguis- tics, Ferdinand de Saussure. Instead, his brother René, a mathematician, who was a major figure in the early twentieth century Esperanto movement (Joseph 2012). Most of his written work was on topics in mathematics and physics, and on Esperanto, but de Saussure (1911) is a short (122 page) book devoted to word structure,1 in which he lays out a view of morphology that anticipates one side of a major theoretical opposition that we will follow below. René de Saussure begins by distinguishing simple words, on the one hand, and com- pounds (e.g., French porte-plume ‘pen-holder’) and derived words (e.g., French violoniste ‘violinist’), on the other. For the purposes of analysis, there are only two sorts of words: root words (e.g. French homme ‘man’) and affixes (e.g., French -iste in violoniste). But “[a]u point de vue logique, il n’y a pas de difference entre un radical et un affixe [. -

Every Language Has Its Grammar

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 4, Issue 5, May 2017, PP 123-129 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0405015 www.arcjournals.org Approaches to the Teaching of Grammar: Methods and Strategies *Arm Mahbuber Rahman1, Md. Sumon Ahmed1 ¹Department of English, Khwaja Yunus Ali University, Sirajgonj, Bangladesh Abstract: Every language has its grammar. Whether it is one’s own mother tongue or second - language that one is learning. The grammar of the language is important. This is because acceptability and intelligibility, both in speech and in writing within as well as outside one’s own circle or group depend on the currently followed basic notions and norms of grammaticality. A knowledge of grammar is perhaps more important to a second- language learner than to a native speaker has intuitively internalized the grammar of the language whereas the second – language learner has to make a conscious effect to master those aspects of the language which account for grammaticality. It is, therefore, necessary for us, to whom English is a second – language, to learn the grammar of the language. So, without the knowledge of the grammar of a particular language, we cannot properly use the language in communication. But question may arise what should be the method and approach to the study of grammar. Several approaches have been followed through the ages for the study of English grammar. The major approaches are the traditional approach, the structural approach, the notional- functional approach and the communicative approach. Keywords: English grammar, language, communication, approach 1. -

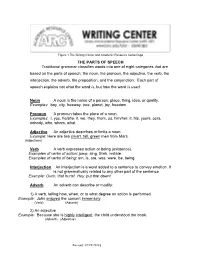

THE PARTS of SPEECH Traditional Grammar Classifies Words Into One

Figure 1 The Writing Center and Academic Resource Center logo THE PARTS OF SPEECH Traditional grammar classifies words into one of eight categories that are based on the parts of speech: the noun, the pronoun, the adjective, the verb, the interjection, the adverb, the preposition, and the conjunction. Each part of speech explains not what the word is, but how the word is used. Noun A noun is the name of a person, place, thing, idea, or quality. Examples: boy, city, freeway, tree, planet, joy, freedom Pronoun A pronoun takes the place of a noun. Examples: I, you, he/she, it, we, they, them, us, him/her, it, his, yours, ours, nobody, who, whom, what Adjective An adjective describes or limits a noun. Example: Here are two smart, tall, green men from Mars. (Adjectives) Verb A verb expresses action or being (existence). Examples of verbs of action: jump, sing, think, imitate. Examples of verbs of being: am, is, are, was, were, be, being Interjection An interjection is a word added to a sentence to convey emotion. It is not grammatically related to any other part of the sentence. Example: Ouch, that hurts! Hey, put that down! Adverb An adverb can describe or modify: 1) A verb, telling how, when, or to what degree an action is performed. Example: John enjoyed the concert immensely. (Verb) (Adverb) 2) An adjective Example: Because she is highly intelligent, the child understood the book. (Adverb) (Adjective) Revised: 07/25/20181 3) Another adverb Example: The pedestrian ran across the street very rapidly. (Verb) (Adverb) (The adverb “rapidly” modifies the verb “ran,” and the adverb “very” modifies the adverb “rapidly.”) Preposition A word that shows the relation of a noun or pronoun to some other word in the sentence. -

The Analysis of Three Approaches in Syntax (Traditional Grammar, Immediate Constituent Analysis and Transformational Grammar): T

Bahari Jogja, Volume XIII Nomor 21, Juli 2015 THE ANALYSIS OF THREE APPROACHES IN SYNTAX (TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR, IMMEDIATE CONSTITUENT ANALYSIS AND TRANSFORMATIONAL GRAMMAR): THEIR STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES IN MARITIME ENGLISH CONTEXT Sri Sartini [email protected] Abstract There are many approaches to analyze English sentence formations. Each approach has got different view upon the analysis of the sentence formation. The aim of this paper is to compare three approaches and this paper tries to compare the use of those three approaches in the production or analysis of English sentences applied in maritime english context. This study is a type of a library research. The conclusion of this paper shows that there are some differences in the perspective use of each approach. Traditional Grammar more focusses on the correct arrangement of the word in the native language and it is based on meaning. Besides it is also based on written language which is considered better than spoken language. Immediate Constituent Analysis focusses the analysis more on the relation of each constituent in a sentence rather than on how the sentence is constructed. Whereas Transformational Grammar which studies on internal language or it is called competence focusses on the grammar which is assumed as a model or systematic description of linguistics competence. From the study It is also known that each syntax approach has their own strengths and weaknesses regarding their use in maritime english subject. Keywords: Syntax, Traditional Grammar, Immediate Constituent Analysis, Transformational Grammar Introduction In relation to the use of language, speakers or writers of a language are able to produce and understand number of utterances or writing. -

Language Theories and Language Teaching—From Traditional Grammar to Functionalism

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 559-565, May 2014 © 2014 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.5.3.559-565 Language Theories and Language Teaching—from Traditional Grammar to Functionalism Yanhua Xia School of Foreign Languages, China West Normal University, Nanchong, China Abstract—linguistic theories have greatly influenced language teaching theories in whatever stage they have been. By reviewing the three main stages of linguistic theories that have existed until now in the history of linguistics, this article has generalized the language teaching theories and the classroom characters resulted from them. Index Terms—language theory, grammar translation method, audio-lingual method, communicative approach It’s universally acknowledged that any new language teaching theory cannot come into being without the break in linguistic theory first. And any generation of linguistic theory has brought about new language teaching theory as well. Until now, the theories of linguistics have mainly experienced three stages: traditional grammar, structuralism and functionalism. They are closely related to each other and generated the change of language teaching theories. I. TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR A. Definition of Traditional Grammar What is traditional grammar? This can be a hard question to answer. One opinion about traditional grammar is that it includes two concepts. One is narrow; another is broad. ―Narrowly speaking, traditional grammar refers to the grammar theories originated from ancient Greece and Rome, which became popular in the end of the 18th century before the birth of historical comparative grammar and dominated the research of grammar and language teaching for a long time in Europe. -

An Introduction to Traditional Grammar

An introduction to Traditional Grammar GRA’MMAR. n. f. [grammaire, French; grammatica, Latin; γραμμαζιχή.] 1. The fcience of fpeaking correctly ; the art which teaches the relations of words to each other. We make a countryman dumb, whom we will not allow to fpeak but by the rules of grammar. Dryden’s Dufrefney. Men, fpeaking language according to the grammar rules of that language, do yet fpeak improperly of things. Locke. 2. Propriety or juftnefs of fpeech; fpeech according to grammar. Varium & mutabile femper femina, is the fharpeft fatire that ever was made on woman; for the adjectives are neuter, and animal muft be underftood to make them grammar. Dryden. 3. The book that treats of the various relations of words to one another. GRA’MMAR School. n. f. A fchool in which the learned languages are grammatically taught. Thou haft moft traitoroufly corrupted the youth of the realm in erecting a grammar fchool. Shakefpeare’s Hen. VI. The ordinary way of learning Latin in a grammer fchool I cannot encourage. GRAMMA’RIAN. n. f. [grammairien, French, from grammar.] One who teaches grammar; a philologer. GRAMMATICASTER. n.f. [Latin.] A mean verbal pedant; a low grammarian. 1. INTRODUCTORY This guide was designed mainly to introduce students who have not been taught grammar at school to some basic grammatical terms and concepts. It is deliberately conservative (and in some ways over-simplified), keeping as far as possible to the terminology of “traditional grammar”, since this is used in most of the dictionaries and textbooks you will be working from. For criticisms of “traditional grammar” and an account of recent developments in grammatical analysis and terminology, consult any recent introductory work on linguistics. -

Sentence Analysis from the Point of View of Traditional, Structural and Transformational Grammars

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences December 2012, Vol. 2, No. 12 ISSN: 2222-6990 Sentence Analysis from the Point of View of Traditional, Structural and Transformational Grammars Ahmed Mohammed S. Alduais Department of English Language, King Saud University KSU, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia KSA Abstract Purpose: To analyse sentence (simple type, statement form) in terms of three types of grammar: traditional, structural and transformational grammars in addition to presenting some hints about analysing sentences which are semantically the same but with different word order, from the point of view of the three grammatical approaches. Method: Reviewing related literature and presenting examples that show the analysis of the sentence according to each grammatical school, briefly. Results: Each type of the three grammatical approaches has different terminology and yet strategy when analysing a sentence. For instance, in traditional grammar the sentence is divided into units, into patterns in structural grammar and into elements and phrases in transformational grammar. In addition, in both traditional and structural grammars, a number of sentences which have identical meanings with different word order are considered totally different from one another when being analysed; whereas, in transformational grammar the sentences share the same base and are analysed in terms of surface and deep structure(s) for each one. Conclusions: The three presented grammatical approaches can be arranged in terms of the most detailed approach as: transformational grammar, traditional, and finally structural grammar. Keywords: simple sentence analysis, traditional grammar, structural grammar, and transformational grammar. Introduction It is totally agreed by most of the world linguists and mainly grammarians that whatever numbers of grammar types we do have; they all basically aim at stating some statements about linguistic units.