September General Meagher's Dispatches[6223]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gary Galyean's Golf Letter

GARY GALYEAN’S ® OLF ETTER® G T H E I N S I D E R E PL O R T O N W O R L D G O L F NUMBER 339 OUR 31st YEAR JULY 2020 Dear Subscriber: The great players always have courses where they shine: Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods at Augusta National, re these times tough or simply chaotic, inconve- Sam Snead at Augusta and Greensboro, Davis Love III at Anient, misinformed and fearful? The three stories Hilton Head and, of course, Young Tom Morris at Prest- that follow are offered about tough individuals, a tough golf wick. For Mr. Hogan, it was Colonial–where he won five course, and some tough times. It’s just golf ... or is it? times; the fifth being his last tour victory. Colonial came th Ben Hogan is widely acknowledged for the disre- to be called Hogan’s Alley, as did Riviera and the 6 hole at gard he had for personal discomfort Carnoustie. and pain. His father killed himself The difficulty of Colonial and the INSIDE THIS ISSUE when Ben was just a child; he slept in fact that it was in Fort Worth must bunkers in order to get the first caddie have brightened Mr. Hogan, whose assignment of the day; and having Hogan and Colonial character was forged in Texas heat by survived a nearly fatal car collision, he McDermott the self-reliance and determination he produced what is considered the great- learned as a boy. “He was the hard- est competitive season ever played. -

For the Second Time in Three Years, the US Open Will Be

Website: centerfornewsanddesign.com PLAYERS 2017 U.S. OPEN • ERIN HILLS TO WATCH Major FACTS DUSTIN JOHNSON & FIGURES Age: 32 117th U.S. Open Country: United States June 15-18 World ranking: 1 Erin Hills Golf Club, Majors: US Open (2016) Mystery Wisconsin Best finish: Won US Open memory: His For the second time in three The course: Wisconsin 6-iron to 5 feet for birdie on developer Robert the 18th at Oakmont to win. Lang was behind the years, the U.S. Open will be held building of a public golf course on pure at a course hosting its first Major pastureland with hopes of attracting championship and is unfamiliar the U.S. Open. The course about 40 miles to many players northwest of Milwau- kee was designed by Michael Hurdzan, Dana Fry and Ron SERGIO GARCIA Whitten. It opened in Age: 37 2006 and was Country: Spain awarded the U.S. World ranking: 5 Open four years later, Majors: Masters (2017) one year after Lang Best finish: Tie for 3rd at had to sell the course. Pinehurst No. 2 in 2005 It has the appearance US Open memory: Playing of links golf, with in the final group with rolling terrain and no Tiger Woods at Bethpage trees, surrounded by Black in 2002 and coping wetlands and a river. (not very well) with the It will be the second pro-Tiger gallery. time in three years that the U.S. Open is Dustin Johnson holds the trophy after winning the U.S. Open at Oakmont Country Club in 2016. He looks to be the first repeat champion held on a public golf since Curtis Strange in 1989. -

Met Open Championship Presented by Callaway 103Rdaugust 21 - 23, 2018 Wykagyl Country Club History of the Met Open Championship Presented by Callaway

Met Open Championship Presented by Callaway 103rdAugust 21 - 23, 2018 Wykagyl Country Club History of the Met Open Championship Presented by Callaway From its inception in 1905 through the 1940 renewal, the Met Open was considered one of the most prestigious events in golf, won by the likes of Gene Sarazen, Walter Hagen, Johnny Farrell, Tommy Armour, Paul Runyan, Byron Nelson, and Craig Wood, in addition to the brothers Alex and Macdonald Smith (who together captured seven Met Opens, with Alex winning a record four times). The second edition of the championship was hosted and sponsored by Hollywood Golf Club, when George Low won in 1906. After an eight-year hiatus overlapping World War II, the Met Open became more of a regional championship, won by many of the top local club professionals, among them Claude Harmon, Jimmy Wright, Jim Albus, David Glenz, Bobby Heins and Darrell Kestner, not to mention such storied amateurs as Chet Sanok, Jerry Courville Sr., George Zahringer III, Jim McGovern, Johnson Wagner, and Andrew Svoboda. The purse was raised to a record $150,000 in 2007, giving the championship added importance. In 2015 the MGA celebrated a major milestone in marking the championship’s 100th playing, won by Ben Polland at Winged Foot Golf Club. In 2017, The MGA welcomed a new Championship Partner, Callaway Golf. Callaway Golf is the presenting sponsor of the Met Open Championship. Eligibility The competition is open to golfers who are: 1. Past MGA Open Champions. 2. PGA Members in good standing in the Metropolitan and New Jersey PGA Sections. -

U.S. Open 1 U.S

U.S. Open 1 U.S. Open Championship 121st Record Book 2021 2 U.S. Open Bryson DeChambeau Wins the 2020 Championship Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods and now Bryson DeChambeau. when DeChambeau laid out his bold strategy, though some They are the three golfers who have captured an NCAA indi- critics derided his intentions. Winning at Winged Foot from vidual title, a U.S. Amateur and a U.S. Open. DeChambeau the rough, they said, couldn’t be done. joined that esteemed fraternity at Winged Foot Golf Club with a performance for the ages on what many consider one Then on Saturday night under floodlights on the practice of the game’s most demanding championship tests. facility following the third round, DeChambeau hit driver after driver, and 3-wood after 3-wood. He hit balls until just DeChambeau carded a final-round, 3-under-par 67 to earn past 8 p.m. when the rest of his competition was either eat- a decisive six-stroke victory over 54-hole leader and wun- ing dinner or setting their alarm clocks. derkind Matthew Wolff, who was vying to become the first U.S. Open rookie to win the title since 20-year-old amateur While he only found six fairways on Sunday, DeChambeau Francis Ouimet in 1913. put on an exquisite display of iron play and putting, hitting 11 of 18 greens and registering 27 putts. Starting the the final “It’s just an honor,” said DeChambeau, who also is the 12th round two strokes back of Wolff, DeChambeau tied the 2019 player to have won a U.S. -

Pga Golf Professional Hall of Fame

PGA MEDIA GUIDE 2012 PGA GOLF PROFESSIONAL HALL OF FAME On Sept. 8, 2005, The PGA of America honored 122 PGA members who have made significant and enduring contributions to The PGA of America and the game of golf, with engraved granite bricks on the south portico of the PGA Museum of Golf in Port St. Lucie, Fla. That group included 44 original inductees between 1940 and 1982, when the PGA Golf Professional Hall of Fame was located in Pinehurst, N.C. The 2005 Class featured then-PGA Honorary President M.G. Orender of Jacksonville Beach, Fla., and Craig Harmon, PGA Head Professional at Oak Hill Country Club in Rochester, N.Y., and the 2004 PGA Golf Professional of the Year. Orender led a delegation of 31 overall Past Presidents into the Hall, a list that begins with the Association’s first president, Robert White, who served from 1916-1919. Harmon headed a 51-member group who were recipients of The PGA’s highest honor — PGA Golf Professional of the Year. Dedicated in 2002, The PGA of America opened the PGA PGA Hall of Fame 2011 inductees (from left) Guy Wimberly, Jim Remy, Museum of Golf in PGA Village in Port St. Lucie, Fla., which Jim Flick, Errie Ball, Jim Antkiewicz and Jack Barber at the Hall paved the way for a home for the PGA Golf Professional Hall of Fame Ceremony held at the PGA Education Center at PGA Village of Fame. in Port St. Lucie, Florida. (Jim Awtrey, Not pictured) The PGA Museum of Golf celebrates the growth of golf in the United States, as paralleled by the advancement of The Professional Golfers’ Association of America. -

Print | Close Window

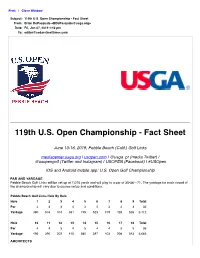

Print | Close Window Subject: 119th U.S. Open Championship - Fact Sheet From: Brian DePasquale <[email protected]> Date: Fri, Jun 07, 2019 1:10 pm To: [email protected] 119th U.S. Open Championship - Fact Sheet June 13-16, 2019, Pebble Beach (Calif.) Golf Links mediacenter.usga.org | usopen.com | @usga_pr (media Twitter) | @usopengolf (Twitter and Instagram) | USOPEN (Facebook) | #USOpen iOS and Android mobile app: U.S. Open Golf Championship PAR AND YARDAGE Pebble Beach Golf Links will be set up at 7,075 yards and will play to a par of 35-36—71. The yardage for each round of the championship will vary due to course setup and conditions. Pebble Beach Golf Links Hole By Hole Hole 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Total Par 4 4 4 4 3 5 3 4 4 35 Yardage 380 516 404 331 195 523 109 428 526 3,412 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Total Par 4 4 3 4 5 4 4 3 5 36 Yardage 495 390 202 445 580 397 403 208 543 3,663 ARCHITECTS Jack Neville and Douglas S. Grant designed Pebble Beach Golf Links, which opened in 1919. WHO CAN ENTER The championship is open to any professional golfer and any amateur golfer with a Handicap Index® not exceeding 1.4. Entries closed on April 24. ENTRIES In 2019, the USGA accepted 9,125 entries, the sixth-highest total in U.S. Open history. The record of 10,127 entries was set in 2014. There were 9,049 entries filed in 2018. -

119Th U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP – FACT SHEET

119th U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP – FACT SHEET June 13-16, 2019, Pebble Beach (Calif.) Golf Links mediacenter.usga.org | usopen.com | @usga_pr (media Twitter) | @usopengolf (Twitter and Instagram) | USOPEN (Facebook) | #USOpen iOS and Android mobile app: U.S. Open Golf Championship PAR AND YARDAGE Pebble Beach Golf Links will be set up at 7,075 yards and will play to a par of 35-36—71. The yardage for each round of the championship will vary due to course setup and conditions. HOLE BY HOLE Hole 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Total Par 4 4 4 4 3 5 3 4 4 35 Yards 380 516 404 331 195 523 109 428 526 3,412 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Total Par 4 4 3 4 5 4 4 3 5 36 Yards 495 390 202 445 580 397 403 208 543 3,663 ARCHITECTS Jack Neville and Douglas S. Grant designed Pebble Beach Golf Links, which opened in 1919. WHO CAN ENTER The championship is open to any professional golfer and any amateur golfer with a Handicap Index® not exceeding 1.4. Entries closed on April 24. ENTRIES In 2019, the USGA accepted 9,125 entries, the sixth-highest total in U.S. Open history. The record of 10,127 entries was set in 2014. There were 9,049 entries filed in 2018. LOCAL QUALIFYING Local qualifying, played over 18 holes, was conducted at 109 sites in the U.S. and one in Canada from April 29- May 13. There were 14 local qualifying sites in both California and Florida, the most of any states. -

Nov-2017.Pdf

MetThe Golfer THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE METROPOLITAN GOLF ASSOCIATION MGAGOLF.ORG In This Issue November 2017 Beyond the Met: Locals once again excelled as they 2 returned to college this fall. People: Montclair’s Mike Strlekar shares tips of the 5 trade that helped him become the 2017 PGA Merchandiser of the Year for Private Facilities. Gear: A variety of technologies makes it easier than 8 ever to find a hybrid that fits your game. Clubs: A growing tradition at Rye Golf Club allows 11 players to tee it up when the sun goes down. Big Picture: Another year of PGA Jr. League once 14 again ended with Royce Brook at the national championship. Travel: Looking for a high-end golf getaway? Los 17 Cabos stands among the greatest options in the world. History: Golf’s historic Smith family created close 19 ties between Carnoustie Golf Club and the Met Area. This page: Is there anything quite like fall golf? This year, the Met Area’s active season was extended to November 14 and MGA Members took advantage of it! There were 19,546 scores posted in the Met Area from Nov. 1-14. (Photo: Par-five 4th at Bethpage Black by AJ Voelpel) BEYOND THE MET MetThe Golfer AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE METROPOLITAN GOLF ASSOCIATION Volume 5, Number 11 • November 2017 he schedule barely lets up for the Met Area’s top collegiate competitors. After busy summers, players returned to their Editor: Tim Hartin T Met Golfer Editorial Committee: Gene M. respective schools in the fall for a full slate of events – with many carrying success from one season to the next. -

120Th U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP – FACT SHEET

120th U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP – FACT SHEET Sept. 17-20, 2020, Winged Foot Golf Club (West Course), Mamaroneck, N.Y. mediacenter.usga.org | usopen.com | @usga_pr (media Twitter) | @usopengolf (Twitter and Instagram) | USOPEN (Facebook) | #USOpen iOS and Android mobile app: U.S. Open Golf Championship PAR AND YARDAGE Winged Foot Golf Club’s West Course will be set up at 7,477 yards and will play to a par of 35-35—70. The yardage for each round of the championship will vary due to course setup and conditions. HOLE BY HOLE Hole 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Total Par 4 4 3 4 4 4 3 4 5 35 Yards 451 484 243 467 502 321 162 490 565 3,685 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Total Par 3 4 5 3 4 4 4 4 4 35 Yards 214 384 633 212 452 426 498 504 469 3,792 ARCHITECTS Winged Foot Golf Club’s West Course was designed by A.W. Tillinghast and opened for play on Sept. 8, 1923. Tillinghast, who also designed Winged Foot’s East Course, competed in two U.S. Opens and eight U.S. Amateurs between 1902 and 1912. Gill Hanse supervised a renovation of the West Course and that work was completed in 2017. He had previously renovated the East Course. ENTRIES The championship is open to any professional golfer and any amateur golfer with a Handicap Index® not exceeding 1.4. Since 2012, the USGA has annually surpassed the 9,000 mark in entries, with a record 10,127 entries accepted for the 2014 U.S. -

43-62 M. Swim History

History & Records Frank Krakowski, a 2005 graduate, owns the longest standing Notre Dame swimming record. His time of 20.45 in the 50-yard freestyle was established during the 2002-03 season. All-Time Year-by-Year Results Year Coach Captain(s) W L Pct. Conference Finish Results 1958-59 Dennis Stark Thomas Londrigan, Richard Nagle 5 5* .500 -- 1959-60 Dennis Stark Eugene Witchger 7 3 .700 -- 1960-61 Dennis Stark Eugene Witchger 7 5 .583 -- First season 1958 (49 seasons) 1961-62 Dennis Stark Joseph Bracco, David Witchger 6 6 .500 -- Overall dual meet record 368-240 (.605) 1962-63 Dennis Stark John MacLeod 6 6 .500 -- Conference titles 9 1963-64 Dennis Stark Charles Blanchard 6 5 .545 -- BIG EAST Championship titles 3 1964-65 Dennis Stark Rory Culhane 5 6 .455 -- BIG EAST Championship runner-ups 4 1965-66 Dennis Stark John Stoltz 6 6 .500 -- BIG EAST Champions 26 1966-67 Dennis Stark Richard Strack 7 3 .700 -- BIG EAST Coach of the Year awards 4 1967-68 Dennis Stark Thomas Bourke 5 6 .455 -- NCAA participants 3 1968-69 Dennis Stark John May 6 6 .500 -- All-American Michael Bulfin 1969-70 Dennis Stark Vincent Spohn 7 7 .500 -- 3-meter Diving (2008) 1970-71 Dennis Stark James Cooney 5 7 .417 -- Academic All-Americans Ted Brown (2007) 1971-72 Dennis Stark Brian Short 7 5 .583 -- Ray Fitzpatrick (2000) 1972-73 Dennis Stark George Block 7 5 .583 -- Most wins (season) 13 1973-74 Dennis Stark Edward Graham 8 4 .667 -- (1987-88, 1990-91) 1974-75 Dennis Stark James Kane 11 1 .917 -- Fewest losses (season) 1 1975-76 Dennis Stark Mark Foster 2 10 .167 -- (1974-75, 1997-98) 1976-77 Dennis Stark William Scott 3 7 .300 -- Highest winning pct. -

Fn OGAN UR Official 1990 Media Guide

fN OGAN UR Official 1990 Media Guide PGA TOUR, SENIOR PGA TOUR, SKINS GAME, STADIUM GOLF, THE PLAYERS CHAMPIONSHIP, TOURNAMENT PLAY- ERS CHAMPIONSHIP, TOURNAMENT PLAYERS CLUB, TPC, TPC INTERNATIONAL, WORLD SERIES OF GOLF. FAMILY GOLF CENTER, TOUR CADDY, and SUPER SENIORS are trade- marks of the PGA TOUR, The BEN HOGAN TOUR is a trademark of the BEN HOGAN COMPANY and is licensed exclusively to the PGA TOUR. PGA TOUR Deane R. Boman. Commissioner Sawgrass Ponte Vedra, FL 32082 Telephone: 904-285-3700 Copyright ©1990 by the PGA TOUR, Inc. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be repro- duced -- electronically, mechanically or by any other means, including photocopying - without the written permission of the PGA TOUR. Cover photo by Hy Peskin, LIFE MAGAZINE © 1950 TIME Inc. BEN HOGAN TOUR OFFICIAL 1990 BEN HOGAN TOUR BOOK Inaugural Edition TOURNAMENT SCHEDULE EXEMPT PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES TOUR INFORMATION TABLE OF CONTENTS 1990 Ben Hogan Tour Schedule.._ ..............................................................3 TourDebuts This Year ................. _ .............................................................. 5 PGA Tournament Policy Board ... ..............................................................6 PGA TOUR Commissioner ...........................................................................7 BenHogan ...................................................... _ ............................................. 9 PGA TOUR Administrators ........................................................................11 Ben Hogan Tour -

SEPTEMBER!! It's Been a Bit of a Wet August. We Thank You

WELCOME SEPTEMBER!! It’s been a bit of a wet August. We thank you for working with us to keep the course in great condition by follow- ing the 90 degree or cart path only rules on the extra wet days. Looking Table of Contents forward to September, its looking like we will have some warm weath- A LOOK FORWARD PG. 2 er with hopefully less rain days. Golf is always fun but even more so A LOOK BACK PG. 3 when you can drive to your ball. Here’s to a wonderful Fall season. NOBODY CARES, PG. 5 MOVE ALONG LIGHTEN UP PG. 8 The Comeback: Ti- PG. 9 ger's journey against the 'Tiger Effect' generation What's coming up PG. 18 Here is a look back though time at some golf history from September. Credit to Colin Brown, USGA https://www.usga.org/clubhouse/2016-ungated/09-ungated/september--this-month-in- golf-history.html Sept. 2, 1973: After failing to qualify in two previous attempts, Craig Stadler won the U.S. Amateur. Then a junior at the University of Southern California who had yet to be dubbed “The Walrus,” Stadler defeated David Strawn, 6 and 5, at Inverness Club in Toledo, Ohio. Sept. 3, 1936 : The USA Walker Cup Team, captained by three-time USGA champion Francis Ouimet, defeated Great Britain and Ireland, 9 -0, at Pine Valley Golf Club. This was the first of two Walker Cups to be played at the venerable New Jersey club, the only USGA champi- onships ever contested there. Sept.