SEPTEMBER!! It's Been a Bit of a Wet August. We Thank You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 CORPORATE PARTNERSHIP OPPORTUNITIES March 23-29, 2015 TPC San Antonio

VALERO TEXAS OPEN 2015 CORPORATE PARTNERSHIP OPPORTUNITIES March 23-29, 2015 TPC San Antonio Steven Bowditch 2014 Champion DATES: It’s been a pretty exciting time. March 23-29, 2015 It’s been a little crazy with all the TITLE SPONSOR: congratulations and autographs. Valero Energy Corporation It’s been really overwhelming; it’s SITE: TPC San Antonio a wonderful experience. AT&T Oaks Course – Steven Bowditch World Golf Hall of Fame member and renowned golf 2014 Champion course architect Greg Norman, together with player consultant and current PGA TOUR star, Sergio Garcia, CONTENTS: masterfully designed the par-72, 7,522-yard AT&T Oaks Course at TPC San Antonio, a part of the JW Marriott H Tournament Facts San Antonio Hill Country Resort and Spa. H Tournament Recap H Growth Trends and Demographics BROADCAST: H Charitable Initiatives Golf Channel & NBC H Sponsors DEFENDING CHAMPION: H 2014 Tournament Players Steven Bowditch (69-67-68-76--280) H Past Champion Highlights H Setting The Stage FIELD SIZE: H Corporate Hospitality & Entertainment 144 Players H Branding H Special Events PRIZE MONEY: $6.2 Million Purse ($1,116,000 to winner) • Pro-Am Experiences • Valero Junior Texas Open TOURNAMENT MANAGED BY: • Night To Honor Our Heroes Presented by USAA • Astellas Presents Executive Women’s Day • Private Corporate Functions 1 2014 TOURNAMENT RECAP GROWTH TRENDS (Percentage Increase from Prior Year) Never before, in the Texas Open’s 92-year history, have so many gathered to experience San Antonio’s annual PGA Attendance DEMOGRAPHICS TOUR stop. Record crowds at TPC San Antonio along with millions of television viewers from around the globe 21.4% witnessed some of the game’s biggest and brightest stars, 200% Gender SA Zip Codes including Phil Mickelson, Matt Kuchar, Jimmy Walker, Zach Johnson, Ernie Els, Jordan Spieth and Jim Furyk 2014 Male 74% 78258 to name just a few, as they navigated their way around 2013 22% 2012 the challenging AT&T Oaks Course in the hopes of being Female crowned Valero Texas Open Champion. -

Word Searches

WORD SEARCHES 1 WORD SEARCH MULTIPLE WINNERS DIRECTIONS: FIND THE WORDS MARKED IN BOLD S V W W H R E M L A P M C V S F O E P A N B V I T O K T N W K I T T R M O A U R F S I A B R A X U N U U S G H S K U G F C A S P E R J A T C D M A O A C Z S G Y G N S J A X Z I H L U O S Y L N U N W Y W X I T Y I N O E J A K E T M I F E R H H A D P L M Y A O F S U M K O L C Z P E P G D E I D H L U N J B C G X R U R Q V V D V I U S C O T T Q Y O Y T S Y V L E B H N O S L E K C I M A L B A Z A V O E H Q O G B P S O T K F M U Y A A N X A V C Q O D R BILLY CASPER, HARRY COOPER, FRED COUPLES, PAUL HARNEY, BEN HOGAN, LLOYD MANGRUM, PHIL MICKELSON, GIL MORGAN, ARNOLD PALMER, COREY PAVIN, ADAM SCOTT, MACDONALD SMITH, SAM SNEAD, LANNY WADKINS, BUBBA WATSON, MIKE WEIR GenesisInvitational.com/KidsClub 1 WORD SEARCH CHARLIE SIFFORD MEMORIAL EXEMPTIONS DIRECTIONS: FIND THE WORDS MARKED IN BOLD W V Z Q X Z J T Z T G D Q Y I A O P T X O T S L N J M R C H L V C Q H E A N K L I S C X Y K T M N L I U J O J N A H F A E A S M H K Z R Q T J L S K D R O A I U A J E K X G L W P R N R X F R A L R G D V O D F I B J E T F T A L I P O P P A M H L W P B U G G M D A F U X S H I L A E N O Z I R N O A V W P L R F M J P N Y U I O C C H K B K Y Y L G V A V O D O H Z H R V A K N W P V A R N E R S C H A M P Q S K C A M S D T L H N T Q F X V F F B D T T Y N JOSEPH BRAMLETT, CAMERON CHAMP, KEVIN HALL, VINCENT JOHNSON, WILLIE MACK III, TIMOTHY O’NEAL, CARLOS SAINZ JR, J.J. -

Teeing Off for 1921 a Brief Glance at the Possible Features for the Coming Season on the Links by Innis Brown

20 THE AMERICAN GOLFER Teeing Off for 1921 A Brief Glance at the Possible Features for the Coming Season on the Links By Innis Brown IGURATIVELY speaking, the golfing lowing have signified a desire to join the on what the Britons are thinking and saying world is now teeing off for the good expeditionary force: Champion "Chick" of the proposal to send over a team. When F year 1921, though as a matter of fact a Evans, Francis Ouimet, "Bobby" Jones, Harry Vardon and Ted Ray arrived back moody, morose and melancholy majority is Davidson Herron, Max R. Marston, Parker home after their extended tour of the States, doing nothing more than casting an occasional W. Whittemore, Nelson M. Whitney, Regi- both Harry and Ted derived no little fun furtive glance in the direction of its links nald Lewis and Robert A. Gardner. It is from telling their friends among the ranks paraphernalia, and maligning the turn of probable that one or two others may be added of home amateurs just what lay in store for weather conditions that have driven it indoors to the above list. them, if America sent over a team. Both pre- for a period of hibernation. But that more This collection of stars will form far and claimed boldly that the time was ripe for fortunate, if vastly outnumbered element away the most formidable array of amateur Uncle Sam to repeat on the feat that Walter which is even now trekking southward, has talent that ever launched an attack against J. Travis performed at Sandwich in 1904, already begun to set the new golfing year when he captured the British title. -

Georgia Hall Ambassadorship Announcement

WENTWORTH NAMES GEORGIA HALL AS AMBASSADOR London, May 2019: Wentworth Club, the world-famous Golf and Country Club, has announced current Women’s British Open title holder Georgia Hall as Ambassador. The 23-year-old English professional golfer will utilise Wentworth’s 3 Geo-certified Championship 18-hole courses as her home training base over the next three years. The former British number one will take full advantage of the vast facilities the Club has to offer; from Championship golf courses, to state-of-the-art driving range and practice facilities, and an overall enhanced wellness offering at the Tennis & Health Club. "I was delighted to be invited to be Ambassador at Wentworth, as I’ve always aspired to have access to leading practice facilities such as theirs. Practice has never been this fun. I’m spoiled by the technology available to support in advancing my game, not to mention the beautiful gym and spa spaces. The Members and all staff at the club have made me feel extremely welcome and I look forward to strengthening my relationship with all.” Georgia Hall “We are delighted to announce that Georgia Hall has joined Wentworth Club as our new golf ambassador. Bringing youth, skill and passion to Wentworth, we are excited by this new relationship and the opportunities it will provide to our Members.” Woraphanit Ruayrungruang (Wentworth Director) www.wentworthclub.com For press enquiries please contact: Kelly Hogarth [email protected] NOTES TO EDITORS About Wentworth Club For more than nine decades Wentworth Club has been regarded as one of the world’s finest and most prestigious golf and country clubs, famous as the home of the BMW PGA Championship since 1984, host venue to the World Match Play for 43 years and the birthplace of the Ryder Cup. -

Best Golf Courses You Can Play in Each State

Best golf courses you can play in each state Here is a state-by-state list of the best golf courses you can play across the United States as selected by Golfweek’s Raters. Courses are listed by preference. Modern courses built after 1960 are denoted with (m), while classic courses built before 1960 are noted with a (c). Alabama 1. FarmLinks at Pursell Farms Sylacagua (m) 2. Grand National (Lake) Opelika (m) 3. Cambrian Ridge (Sherling/Canyon) Greenville (m) 4. Ross Bridge Hoover (m) 5. Grand National (Links) Opelika (m) 6. Kiva Dunes Gulf Shores (m) 7. Oxmoor Valley (Ridge) Birmingham (m) 8. The Shoals (Fighting Joe) Muscle Shoals (m) 9. Limestone Springs Oneonta (m) 10. Magnolia Grove (The Crossings) Mobile (m) Alaska 1. Anchorage GC Anchorage (m) 2. Moose Run (Creek) Fort Richardson (m) 3. Chena Bend Fairbanks (m) 4. Settler’s Bay Wasilla (m) 5. Moose Run (Moose) Fort Richardson (m) Arizona 1. We-Ko-Pa (Saguaro) Fountain Hills (m) 2. Ritz-Carlton Golf Club at Dove Mountain Marana (m) (Saguaro/Tortolita) 3. Quintero Peoria (m) 4. Verrado Buckeye (m) 5. Wickenburg Ranch Wickenburg (m) 6. TPC Scottsdale (Stadium) Scottsdale (m) 7. Troon North (Monument) Scottsdale (m) 8. Troon North (Pinnacle) Scottsdale (m) 9. Ak-Chin Southern Dunes Maricopa (m) 10. We-Ko-Pa (Cholla) Fountain Hills (m) 11. Ventana Canyon (Mountain) Tucson (m) 12. Boulders Resort (North) Carefree (m) 13. Boulders Resort (South) Carefree (m) 14. Grayhawk (Raptor) Scottsdale (m) 15. La Paloma (Ridge/Canyon) Tucson (m) 16. Apache Stronghold San Carlos (m) 17. Laughlin Ranch Bullhead City (m) 18. -

2021 PURE Insurance Press Release

MEDIA CONTACTS: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sara Henika, First Tee [email protected] 904-940-4341 81 First Tee Teens Selected for PGA TOUR Champions’ PURE Insurance Championship Impacting the First Tee at Pebble Beach Golf Channel’s Damon Hack and Shane Bacon, PGA TOUR’s Ryan Palmer and Commissioner Jay Monahan surprise teens with invitation to event PONTE VEDRA, Fla. (July 6, 2021) – First Tee and PGA TOUR Champions announced today the 81 First Tee participants selected to play in the 2021 PURE Insurance Championship Impacting the First Tee. The event, in its 18th year, will bring teens from First Tee chapters to Pebble Beach Golf Links and Spyglass Hill Golf Course for the PGA TOUR Champions tournament, Sept. 20-26. The annual event, hosted by the Monterey Peninsula Foundation, is televised internationally on Golf Channel. Throughout the week the teens apply the life and leadership skills learned from First Tee programs during the one-of-a-kind event where they are paired with a PGA TOUR Champions player and amateurs from the business world. Ranging in ages from 15 to 19, the First Tee participants compete for the Pro-Junior Team title. The teens represent 48 First Tee chapters from across the country and for the first time a participant from First Tee — Morocco will be in the field. Participants were selected by a national panel of judges based on their personal growth and life skills learned through First Tee’s programs, as well as their playing ability. The full junior field was revealed live on Golf Channel’s “Golf Today” including a video of PGA TOUR Commissioner Jay Monahan surprising Madelyn Campbell, Matthew French and Grace Richards from First Tee — North Florida. -

Gary Galyean's Golf Letter

GARY GALYEAN’S ® OLF ETTER® G T H E I N S I D E R E PL O R T O N W O R L D G O L F NUMBER 339 OUR 31st YEAR JULY 2020 Dear Subscriber: The great players always have courses where they shine: Jack Nicklaus and Tiger Woods at Augusta National, re these times tough or simply chaotic, inconve- Sam Snead at Augusta and Greensboro, Davis Love III at Anient, misinformed and fearful? The three stories Hilton Head and, of course, Young Tom Morris at Prest- that follow are offered about tough individuals, a tough golf wick. For Mr. Hogan, it was Colonial–where he won five course, and some tough times. It’s just golf ... or is it? times; the fifth being his last tour victory. Colonial came th Ben Hogan is widely acknowledged for the disre- to be called Hogan’s Alley, as did Riviera and the 6 hole at gard he had for personal discomfort Carnoustie. and pain. His father killed himself The difficulty of Colonial and the INSIDE THIS ISSUE when Ben was just a child; he slept in fact that it was in Fort Worth must bunkers in order to get the first caddie have brightened Mr. Hogan, whose assignment of the day; and having Hogan and Colonial character was forged in Texas heat by survived a nearly fatal car collision, he McDermott the self-reliance and determination he produced what is considered the great- learned as a boy. “He was the hard- est competitive season ever played. -

For the Second Time in Three Years, the US Open Will Be

Website: centerfornewsanddesign.com PLAYERS 2017 U.S. OPEN • ERIN HILLS TO WATCH Major FACTS DUSTIN JOHNSON & FIGURES Age: 32 117th U.S. Open Country: United States June 15-18 World ranking: 1 Erin Hills Golf Club, Majors: US Open (2016) Mystery Wisconsin Best finish: Won US Open memory: His For the second time in three The course: Wisconsin 6-iron to 5 feet for birdie on developer Robert the 18th at Oakmont to win. Lang was behind the years, the U.S. Open will be held building of a public golf course on pure at a course hosting its first Major pastureland with hopes of attracting championship and is unfamiliar the U.S. Open. The course about 40 miles to many players northwest of Milwau- kee was designed by Michael Hurdzan, Dana Fry and Ron SERGIO GARCIA Whitten. It opened in Age: 37 2006 and was Country: Spain awarded the U.S. World ranking: 5 Open four years later, Majors: Masters (2017) one year after Lang Best finish: Tie for 3rd at had to sell the course. Pinehurst No. 2 in 2005 It has the appearance US Open memory: Playing of links golf, with in the final group with rolling terrain and no Tiger Woods at Bethpage trees, surrounded by Black in 2002 and coping wetlands and a river. (not very well) with the It will be the second pro-Tiger gallery. time in three years that the U.S. Open is Dustin Johnson holds the trophy after winning the U.S. Open at Oakmont Country Club in 2016. He looks to be the first repeat champion held on a public golf since Curtis Strange in 1989. -

PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y

. OP U.S EN SHINNECOCK HILLS TH 118TH U.S. OPEN PLAYERS GUIDE — Shinnecock Hills Golf Club | Southampton, N.Y. — June 14-17, 2018 conducted by the 2018 U.S. OPEN PLAYERS' GUIDE — 1 Exemption List SHOTA AKIYOSHI Here are the golfers who are currently exempt from qualifying for the 118th U.S. Open Championship, with their exemption categories Shota Akiyoshi is 183 in this week’s Official World Golf Ranking listed. Birth Date: July 22, 1990 Player Exemption Category Player Exemption Category Birthplace: Kumamoto, Japan Kiradech Aphibarnrat 13 Marc Leishman 12, 13 Age: 27 Ht.: 5’7 Wt.: 190 Daniel Berger 12, 13 Alexander Levy 13 Home: Kumamoto, Japan Rafael Cabrera Bello 13 Hao Tong Li 13 Patrick Cantlay 12, 13 Luke List 13 Turned Professional: 2009 Paul Casey 12, 13 Hideki Matsuyama 11, 12, 13 Japan Tour Victories: 1 -2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Kevin Chappell 12, 13 Graeme McDowell 1 Open. Jason Day 7, 8, 12, 13 Rory McIlroy 1, 6, 7, 13 Bryson DeChambeau 13 Phil Mickelson 6, 13 Player Notes: ELIGIBILITY: He shot 134 at Japan Memorial Golf Jason Dufner 7, 12, 13 Francesco Molinari 9, 13 Harry Ellis (a) 3 Trey Mullinax 11 Club in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan, to earn one of three spots. Ernie Els 15 Alex Noren 13 Shota Akiyoshi started playing golf at the age of 10 years old. Tony Finau 12, 13 Louis Oosthuizen 13 Turned professional in January, 2009. Ross Fisher 13 Matt Parziale (a) 2 Matthew Fitzpatrick 13 Pat Perez 12, 13 Just secured his first Japan Golf Tour win with a one-shot victory Tommy Fleetwood 11, 13 Kenny Perry 10 at the 2018 Gateway to The Open Mizuno Open. -

Turning Back the Clock on Usga Work for Golf

By JOSEPH C. DEY, JR. TURNING BACK THE CLOCK Executive Director United states Golf ON USGA WORK FOR GOLF Association • Based on remarks prepared for 1961 Educational Program of Professional Golfers' Association of America here's always danger in looking back- "Those new built-in- gyroscopes in this T ward. You may become so enchanted ball surely keep it on line, don't they?" with where you've come from that you he remarks. He plays a medium iron forget where you're headed for. All of us whO'se shaft is attached to the head sometimes sigh for "the good old days," right in the middle, behind the sweet and that can keep us from taking deep spot-"Gives more power and reduces breaths in the fresh air of the present. torque," he explains, as the ball sits But a view of history can be profitable. down four feet from the cup. There is real value in stock-taking, in Jack, in the fairway, picks up his ball recalling what was good and useful, and and places it on a little tuft of grass. "I what was not, with a view to handling hate cuppy lies," he says. He plays the the future properly. new club, and the ball does a little jig Let's first take a look at the USGA's before snuggling down two feet from the past through some rather distorted hole. glasses-by imagining what might be the As Jack gets Qut of his midget heli- case today if the USGA had been radi- copter at the parking space alQngside cally different or if there had never been the green, he finds Gene moaning: "I'd a USGA. -

119Th U.S. OPEN NOTEBOOK and STORY IDEAS June 13-16, 2019 Pebble Beach (Calif.) Golf Links

119th U.S. OPEN NOTEBOOK AND STORY IDEAS June 13-16, 2019 Pebble Beach (Calif.) Golf Links mediacenter.usga.org | usopen.com | @usga_pr (media Twitter) | @usopengolf (Twitter and Instagram) | USOPEN (Facebook) | #USOpen iOS and Android mobile app: U.S. Open Golf Championship WHO’S HERE: Among the 156 golfers in the 2019 U.S. Open, there are: U.S. Open champions (12): Ernie Els (1994, ’97), Jim Furyk (2003), Lucas Glover (2009), Dustin Johnson (2016), Martin Kaymer (2014), Brooks Koepka (2017, ’18), Graeme McDowell (2010), Rory McIlroy (2011), Justin Rose (2013), Webb Simpson (2012), Jordan Spieth (2015) and Tiger Woods (2000, ’02, ’08). U.S. Open runners-up (13): Jason Day (2011, ’13), Ernie Els (2000), Tommy Fleetwood (2018), Rickie Fowler (2014), Jim Furyk (2006, ’07, ’16), Dustin Johnson (2015), Shane Lowry (2016), Hideki Matsuyama (2017), Graeme McDowell (2012), Phil Mickelson (1999, 2002, ’04, ’06, ’09, ’13), Louis Oosthuizen (2015), Scott Piercy (2016) and Tiger Woods (2005, ’07). U.S. Amateur champions (7): Byeong Hun An (2009), Bryson DeChambeau (2015), Matthew Fitzpatrick (2013), Viktor Hovland (2018), Matt Kuchar (1997), Phil Mickelson (1990) and Tiger Woods (1994, ’95, ’96). U.S. Amateur runners-up (3): Devon Bling (2018), Luke List (2004) and Patrick Cantlay (2011). U.S. Junior Amateur champions (4): Jordan Spieth (2009, ’11), Scottie Scheffler (2013), Michael Thorbjornsen (2018) and Tiger Woods (1991, ’92, ’93). U.S. Junior Amateur runners-up (3): Aaron Baddeley (1998), Charles Howell III (1996) and Justin Thomas (2010). U.S. Senior Open champions (1): David Toms (2018). U.S. Senior Open runners-up (0): none. -

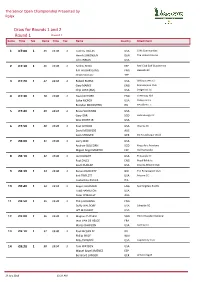

Draw for Rounds 1 and 2 Round 1 Round 2 Game Time Tee Game Time Tee Name Country Attachment

The Senior Open Championship Presented by Rolex Draw for Rounds 1 and 2 Round 1 Round 2 Game Time Tee Game Time Tee Name Country Attachment 1 07:00 1 25 11:30 1 Tommy TOLLES USA Cliffs Communities Henrik SIMONSEN DEN The Honors Course John INMAN USA 2 07:10 1 26 11:40 1 Andres ROSA ESP Real Club Golf Guadalmina B.R. HUGHES (AM) ENG Hesketh GC Chien Soon LU TPE 3 07:20 1 27 11:50 1 Robert BURNS USA Willow Creek GC Gary MARKS ENG Roehampton Club Chip LUTZ (AM) USA Ledgerock GC 4 07:30 1 28 12:00 1 David GILFORD ENG Greenway Hall Spike MCROY USA Valley Hill CC Brendan MCGOVERN IRL Headfort G.C 5 07:40 1 29 12:10 1 Bruce VAUGHAN USA Gary ORR SCO Helensburgh GC Wes SHORT JR USA 6 07:50 1 30 12:20 1 Paul GOYDOS USA Virginia CC David MCKENZIE AUS Sven STRÜVER GER GC Teutoburger Wald 7 08:00 1 31 12:30 1 Larry MIZE USA Andrew OLDCORN SCO Kings Acre Academy Miguel Angel MARTIN ESP Golf Santander 8 08:10 1 32 12:40 1 Joe DURANT USA Pensacola CC Paul EALES ENG Royal Birkdale Scott DUNLAP USA Atlanta Athletic Club 9 08:30 1 33 13:00 1 Ronan RAFFERTY NIR The Renaissance Club Kirk TRIPLETT USA Arizona CC Costantino ROCCA ITA 10 08:40 1 34 13:10 1 Roger CHAPMAN ENG Sportingclass Events Todd HAMILTON USA Peter O'MALLEY AUS 11 08:50 1 35 13:20 1 Philip GOLDING ENG Duffy WALDORF USA Lakeside GC Jeff MAGGERT USA 12 09:00 1 36 13:30 1 Magnus P ATLEVI SWE PGA of Sweden National Jean VAN DE VELDE FRA Marco DAWSON USA Suntree CC 13 09:10 1 37 13:40 1 Paul MCGINLEY IRL Phillip PRICE WAL Billy ANDRADE USA Capital City Club 14 09:20 1 38 13:50 1 Tom WATSON USA