Scottish Benedictine Houses of the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News from Tobias Parker Many Of

News from The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham in Scotland www.ordinariate.scot Pilgrimage 2016 Issue Celebrating Saint Andrew in this▸ issue... Ordinariate Pilgrimage to St Andrews ? Pilgrimage ? New Ordinariate HE ORDINARIatE is on Monsignor Keith Newton writes: members TPilgrimage throughout the UK “Pilgrimage holds a special place ? Bl John Henry during this Jubilee Year of Mercy. in the Ordinariate of Our Lady Newman ‘miracle’ They began in North Wales at the of Walsingham. For many of us, ? New Ordinariate Shrine of St Winifrede at Holywell, pilgrimages to the shrine from Mass routine and as you read this, Mgr Keith which we take our name have been Newton, will be in Rome and central to our spiritual life. Loreto with a group of Ordinariate Pilgrims. “Our entry as members of the Ordinariate into the full communion of the Catholic ? First Ecumenical Church was in itself a pilgrimage Chapel in – travelling together, often at some Scotland personal cost, to answer God’s ? Mgr Newton’s call and to receive His grace. It is Scottish visit natural therefore that pilgrimage should be at the heart of our observance of the Year of Mercy.” The Apostle Andrew was the first disciple to follow Jesus. He was present during the Last Supper and in the Garden at Gethsemane. He saw the Risen ? The Oratory Christ after the Resurrection ? Lent Appeal and was amongst those who ? On-line Shopping received the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. According to ? Welcome tradition, Andrew left the Holy ? Holy Land and Land after Pentecost to spread Poland the Word in Greece and Asia ? Abbey establishes This will be followed by a Minor. -

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No

DUNKELD NEWS Diocesan Newsletter of the Bishop of Dunkeld No. 18 December 2019 INDSIDE - Parish news stories; Lourdes reports, Our pilgrims in Spain and Italy, Schools and Youth News Emotional welcome for the Little Flower What a grace-filled event it was for our for everyone present. It seemed to everyone diocese to have the relics of St Therese of that her saintly presence was enough as she Lisieux visit us in our own St Andrews spoke in the silence of everyone’s heart. Cathedral in September. It was as though Therese, one of the most popular saints in Therese had come not for herself but for the history of the Church, had indeed come everyone in every diocese in Scotland and to visit us to inspire us, to encourage us, the people present were delighted that she and just to be present with us for a few days was really here in our Diocese of Dunkeld where she will listen to us and speak to us with devotees, young and old, who loved in the depths of our hearts. Never has the her and wished to spend some time in her Cathedral been so bedecked with so many physical and spiritual presence. Most of all beautiful roses, symbols of her great love to learn from her. The good humour spread Fr Anthony McCarthy, parish priest for God and her promise to all of her devo- quickly among the congregation, and the of Our Lady of Good Counsel, Broughty tees. sense of incredulity at her closeness was Ferry, died on Thursday 10th October, awesome. -

126613853.23.Pdf

Sc&- PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME LIV STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH OCTOBEK 190' V STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH 1225-1559 Being a Translation of CONCILIA SCOTIAE: ECCLESIAE SCOTI- CANAE STATUTA TAM PROVINCIALIA QUAM SYNODALIA QUAE SUPERSUNT With Introduction and Notes by DAVID PATRICK, LL.D. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1907 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION— i. The Celtic Church in Scotland superseded by the Church of the Roman Obedience, . ix ir. The Independence of the Scottish Church and the Institution of the Provincial Council, . xxx in. Enormia, . xlvii iv. Sources of the Statutes, . li v. The Statutes and the Courts, .... Ivii vi. The Significance of the Statutes, ... lx vii. Irreverence and Shortcomings, .... Ixiv vni. Warying, . Ixx ix. Defective Learning, . Ixxv x. De Concubinariis, Ixxxvii xi. A Catholic Rebellion, ..... xciv xn. Pre-Reformation Puritanism, . xcvii xiii. Unpublished Documents of Archbishop Schevez, cvii xiv. Envoy, cxi List of Bishops and Archbishops, . cxiii Table of Money Values, cxiv Bull of Pope Honorius hi., ...... 1 Letter of the Conservator, ...... 1 Procedure, ......... 2 Forms of Excommunication, 3 General or Provincial Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 8 Aberdeen Synodal Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, 30 Ecclesiastical Statutes of the Thirteenth Century, . 46 Constitutions of Bishop David of St. Andrews, . 57 St. Andrews Synodal Statutes of the Fourteenth Century, vii 68 viii STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH Provincial and Synodal Statute of the Fifteenth Century, . .78 Provincial Synod and General Council of 1420, . 80 General Council of 1459, 82 Provincial Council of 1549, ...... 84 General Provincial Council of 1551-2 ... -

Talking Gothic! What Do We Mean by Gothic Architecture and How Can We Identify It?

Talking Gothic! What do we mean by Gothic architecture and how can we identify it? ‘Gothic’ is the name we give to a style of architecture from the Middle Ages. It is usually thought to have begun near Paris in the middle of the 1100s and, from there, it spread throughout Europe and continued into the 16th century. There are many marvellous examples of Gothic buildings throughout Scotland: from Elgin Cathedral in Moray, through amazing buildings like Glasgow Cathedral, Paisley Abbey and Edinburgh St Giles, down to Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders. All of these, and more, are well worth a visit! Gothic architecture developed from an earlier style we call Romanesque. Buildings made in the Romanesque style often have rounded arches on their (usually comparatively small) windows and doors, thick columns and walls, lots of ornamental patterns, and shorter structures than the buildings which came later. Dunfermline Abbey is a great example of a Romanesque building in Scotland. The people who paid for the earliest Gothic buildings expressed a wish to transport worshippers to a kind of Heaven on Earth by building higher and brighter churches. What emerged is what we now describe as Gothic. Fashions changed throughout the time that Gothic was the predominant style, and it also varied from place to place. However, the Classical revival made popular as part of the Italian Renaissance largely replaced the Gothic style, and it wasn’t fashionable again until the 19th century. During the Romantic Movement Medieval literature, arts and crafts enjoyed renewed popularity. As a result, Glasgow Cathedral was begun in the Gothic elements can be seen today in the churches, public buildings, and late 12th century and was at the hub of the Medieval city. -

Scotland Has a New Bishop

50TH ANNIVERSARY IEC 2012 in Dublin OUR OWN DIAMOND JUBILEE: Bishop offers chance for renewal ahead of Year Emeritus John Mone of Paisley marks of Faith; Scottish bishops report the 60th anniversary of his ordination Pages 3, 8, 11 and online to the priesthood. Pag e 5 No 5471 www.sconews.co.uk Friday June 15 2012 | £1 Archbishop Conti Scotland has a new bishop warns of plight I Cardinal, archbishop and asylum seekers Papal nuncio raise Mgr Stephen face in Glasgow Robson up to the ‘high priesthood’ as Auxiliary Bishop By Martin Dunlop of St Andrews and Edinburgh ARCHBISHOP Mario Conti of THE Episcopal ordination of the newest Glasgow has member of the Bishops’ Conference of Scot- warned of a land was a formal yet joyful celebration in potential Edinburgh last Saturday afternoon that united ‘humanitarian St Andrews and Edinburgh Archdiocese, scandal’ facing Scotland and the Episcopal conferences of around 100 asy- the UK and Ireland. lum seekers in The diverse congregation at St Mary’s Cathe- Scotland who dral in Edinburgh watched as Cardinal Keith face eviction. O’Brien, Archbishop of St Andrews and Edin- The Glasgow burgh, Archbishop Mario Conti of Glasgow and archbishop (right) Apostolic Nuncio Archbishop Antonio Mennini has spoken out against the ‘eviction and com- ordained Archdiocesan Chancellor Mgr Robson, pulsory destitution’ of around 100 people who 61, as Auxiliary Bishop to assist the cardinal in the have come to Scotland to seek asylum, but administration of the archdiocese. Bishop Robson, whose applications have been refused. -

Gavin Douglas Was Born to Be Conservative. Embedded in Feudalism and the Pre Counter Reformation Church He Was Not the Kind of Person to Cause a Ripple in History

12 TWO ASPECTS OF GAVIN DOUGLASO Gavin Douglas was born to be conservative. Embedded in feudalism and the pre Counter Reformation church he was not the kind of person to cause a ripple in history. Literature gave him his fame. There single handed with his translation of Vergil's Aeneid he brought Scotland into the Renaissance. History robbed him of the influence he might have had. The manuscripts of his Aeneid were put away and forgotten, and by the time they were brought to light his language had become obsolete, so now a not infrequent response to the mention of his name is 'Who's he?'. 'He' was two years younger than James IV and finished his Aeneid translation in 1513, the same year as Flodden. Flodden was especially tragic because it came at a time when the nobles, of whom so many fell, were still very important to Scotland. In England and France feudalism might be looking at the beginning of the end because substitution of money for service was making barons no longer indispensable, but in Scotland not only was Lowland feudalism influenced by Highland clan ideals but the continual succession to the throne of minors had nobles playing an indispensable if not always concerted part in government. When Gavin Douglas was a boy feudalism was fighting fit. James III was the king who upset the nobles by preferring the company of a group of commoners to theirs. He more than upset them when he conferred a title on his architect friend Cochrane. Cochrane not only upgraded his attire and took to going round with a small entourage, which after all was only airs and graces, but he also interposed himself between the king and petitioners. -

106 Proceedings of the Society, 1952-53. Scottish

106 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 1952-53. VI. SCOTTISH BISHOPS' SEES BEFOR E REIGTH EF NO DAVID I. BY GORDON DONALDSON, M.A., PH.D., D.LiTT., F.S.A.ScoT. The attribution to David I of the establishment of most of the Scottish episcopal sees has, if only through repetition, become a convention. Yet, while historians have bee generan ni l agreement about David's work, they have differed profoundly as to the details. A very recent writer has gone so far as to remark, "Before David's time St Andrews was the only bishopric Scotlann i d proper addedmorr e o h ; x esi probably eight." 1 Other modern historians have allowe r thredo thao e tw tsee s were founde e reigth nn i d of David's predecessor, Alexander I.2 The older historians and chroniclers were less confident about the extent of David's work. Boece attributed to Davi foundatioe dth onlf no y four bishoprics addition i , previouslx si o nt y existing,3 and he was followed by George Buchanan.4 John Major says of David, "Finding four bishoprics in his kingdom, he founded nine more." 8 Two versions of Wyntoun, again, tell each a different story: Bischopriki fan e t thresh dbo ; deite Both . i lefr x ,o he ,t Or Bischopis he fande bot foure or thre; Bot, or he deit, ix left he.6 This confusion might have suggested tha e conventioth t n requires critical examination. The source of the convention is undoubtedly the Scotichronicon; but the Scotichronicon is content to reproduce the statement of David's contemporary, Ailred of Rievaulx,7 who says something quite different from all later works, versione th wit f exceptioe o hWyntoun f th e o s on sayf e no H se .tha th n ti 1 Mackenzie, W. -

Green Light Signals Quest for Auxiliary

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the preaching of Thy Word and the praising of Thy Name JULY 2015 JOURNAL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW 70p Joie de vivre! A SPIRIT of joy filled St Andrew’s Cathedral as children and young people with additional support needs joined Archbishop Philip Tartaglia for Mass. The theme ‘Rejoice’ reflected the Gospel passage of Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth – whose child in her womb leapt for joy. The Archbishop spoke of the gifts of life and love and the great joy which the births of John the Baptist and Jesus brought to the world. He encouraged the young people to rejoice and reflect that joy in caring for others and looking after the world. Glasgow Lord Provost Sadie Docherty joined in the celebrations. Picture by Paul McSherry Green light Caritas Glasgow to get signals quest Award another bishop for auxiliary Pope Francis has agreed diocesan bishop’s closest col - with Bishop Joseph Devine the green light to his request, By Vincent Toal laborator, he is expected to be who moved to Motherwell in Archbishop Tartaglia has in - to provide an auxiliary involved in all pastoral proj - 1983. Bishop John Mone then vited people to write to him by bishop for the Arch- an auxiliary following his ects, decisions and diocesan served as auxiliary for four 15 August with preferred pages diocese of Glasgow fol - health scare at the beginning initiatives. years before his appointment names. lowing a request from of the year. With Glasgow embarked on to Paisley in 1988. He will then make a formal 6,7,10,11 Archbishop Philip In an ad clerum letter, sent a wide-ranging review of Although usually chosen submission to the Apostolic out this week, he stated: “I am parish pastoral provision, the from among the diocesan Nuncio who conducts a Tartaglia. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

In Search of Dunfermline Abbey's Lost Medieval Choir

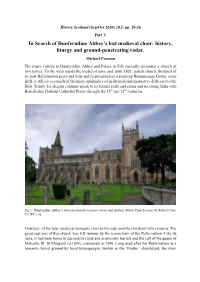

History Scotland (Sep/Oct 2020) 20.5, pp. 20-26 Part 1: In Search of Dunfermline Abbey’s lost medieval choir: history, liturgy and ground-penetrating radar. Michael Penman The many visitors to Dunfermline Abbey and Palace in Fife typically encounter a church of two halves. To the west stands the medieval nave and, until 1821, parish church. Stripped of its post-Reformation pews and lofts and re-presented as a stunning Romanesque-Gothic stone shell, it still coveys much of the misty spirituality of its Benedictine monastery dedicated to the Holy Trinity. Its elegant columns speak to its former scale and status and its strong links with Benedictine Durham Cathedral Priory through the 11th and 12th centuries. Fig 1: Dunfermline Abbey’s buttressed medieval nave (west) and modern Abbey Church (east) [© Robert Cutts, CC BY 2.0] However, of the later medieval monastic choir to the east (and the cloisters) little remains. The great east-end of this church was left ruinous by the iconoclasm of the Reformation. Like its nave, it had been home to successive royal and aristocratic burials and the cult of the queen of Malcolm III, St Margaret (d.1093), canonised in 1249. Long used after the Reformation as a romantic burial ground by local townspeople, known as the ‘Psalter’ churchyard, the choir ruins were eventually cleared and overbuilt c.1817-21 to make way for a new Presbyterian ‘Abbey Church’ of Dunfermline parish, conjoined to the nave. Fig 2: The fossiliferous marble base of St Margaret’s feretory shrine within her east-end chapel, outside the Abbey Church vestry [Author’s photograph]. -

Inventory of Pifirrane Writs 1230

^ Scottish Record Society, Edinburgh Scottish Record Society pgi'sl ,oj. J> I -^rroule. / Cut ^\ ( SCOTTISH RECORD SOCIETY ^ ^ no. (3-^ .. INVENTORY OF PITFIRRANE WRITS 1230-1794 EDITED BY WILLIAM ANGUS CURATOR OF HISTORICAL RECORDS, H.M. GENERAL REGISTKR HOUSE EDINBURGH: PRINTED FOR THE SOCIETY BY J. SKINNER & COMPANY, LTD. 1932 PREFACE. THE Inventory of Pitfirrane Writs here printed is from a collection of Inventories of Titles presented to the Register House by the Trustees of the late Sir William Eraser, K.C.B., LL.D. The Trustees of the late Sir Peter Arthur Halket of Pitfirrane have kindly given their consent to its publication. Mr. Walter Macfarlane of that Ilk, the well-known antiquary, appears to have examined the Pitfirrane charter chest and to have made notes of its contents from which Sir Robert Douglas compiled his account of the family of Halket of Pitfirran for his Baronage of Scotland} . These notes are not in the Macfarlane Collection in the National Library of Scotland. The Inventory here printed bears to have been "prepared by W. Whytock" in 1834, but whether it is based on Macfarlane's work or not it is impossible to say. There can be no doubt that in the absence of a more com- plete Calendar it provides a key to a most interesting and extensive collection of charters which throws much light on various Fife families and lands. Mr. J. C. Gibson and the Rev. William Stephen, D.D., had access to the manuscript, the former when writing The Wardlaws in Scotland and the latter for his History of Inverkeithing and Rosyth, and derived much valuable informa- tion from it. -

Missions in Chonological Order

MISSIONS TO AND FROM SCOTLAND IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER Hiram Morgan 1 FROM DENMARK (1473/4) An esquire of the king of Denmark Envoy Lodged at Snowdon herald's house; K of SC entrusted him with buying munitions in DK when departing. HiramTA 1 pp. lv, 68, 69. Morgan 2 FROM ENGLAND (1474) Bishop of Durham; Lord Scrope; & two others +or inc. herald October 1474 Ambassadors Betrothal (Oct 18), Marriage treaty (21 Oct) & renewal of 1465 truce til 1519. HiramTA 1 pp lvii-ix, 27, 52 Morgan 3 . TO GERMANY/EMPIRE (1474) Snowdon herald 11 May 1474 - date of payment before departure £30 in expenses & £15 for gown Parliament had suggested an embassy to make a confederation with HiramEmperor. TA 1 pp.lvi, 50 Morgan 4 TO ENGLAND (1474)-1 Bp of Aberdeen, Sir John Colquhoun of Luss, James Schaw of Sauchy; Lyon herald. Commission 15 June 1474. July in London. Ambassadors Hiram£20 prepayment to Lyon. Embassy suggested by parliament for treaty confirmation, redress & possible marriage alliance between infant prince of Scotland and Cecilia, daughter of Ed IV. TA 1 lv-vi. Morgan 5 TO ENGLAND (1474)-2 Lyon herald Leaves after 3 Nov, signs document in London on 3 Dec 3 Nov 1474 J3 signs articles of peace & Lyon proceeds to London 'for the interchanging of the truces'. 3 Dec LH signs indenture re remission of Cecilia's dowry HiramTA 1 p.lix. Morgan 6 TO ITALY (ROME) (1474) Lombard bankers 1474 The king's appeal against the abp of St Andrews at Rome - the K's interests represented by Lombard bankers.