(Pyrgulopsis Spp.) in and Adjacent to the Spring Mountains, Nevada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habitat Usage by the Page Springsnail, Pyrgulopsis Morrisoni (Gastropoda: Hydrobiidae), from Central Arizona

THE VELIGER ᭧ CMS, Inc., 2006 The Veliger 48(1):8–16 (June 30, 2006) Habitat Usage by the Page Springsnail, Pyrgulopsis morrisoni (Gastropoda: Hydrobiidae), from Central Arizona MICHAEL A. MARTINEZ* U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2321 W. Royal Palm Rd., Suite 103, Phoenix, Arizona 85021, USA (*Correspondent: mike[email protected]) AND DARRIN M. THOME U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2800 Cottage Way, Rm. W-2605, Sacramento, California 95825, USA Abstract. We measured habitat variables and the occurrence and density of the Page springsnail, Pyrgulopsis mor- risoni (Hershler & Landye, 1988), in the Oak Creek Springs Complex of central Arizona during the spring and summer of 2001. Occurrence and high density of P. morrisoni were associated with gravel and pebble substrates, and absence and low density with silt and sand. Occurrence and high density were also associated with lower levels of dissolved oxygen and low conductivity. Occurrence was further associated with shallower water depths. Water velocity may play an important role in maintaining springsnail habitat by influencing substrate composition and other physico-chemical variables. Our study constitutes the first empirical effort to define P. morrisoni habitat and should be useful in assessing the relative suitability of spring environments for the species. The best approach to manage springsnail habitat is to maintain springs in their natural state. INTRODUCTION & Landye, 1988), is medium-sized relative to other con- geners, 1.8 to 2.9 mm in shell height, endemic to the The role that physico-chemical habitat variables play in Upper Verde River drainage of central Arizona (Williams determining the occurrence and density of aquatic micro- et al., 1985; Hershler & Landye, 1988; Hershler, 1994), invertebrates in spring ecosystems has been poorly stud- with all known populations existing within a complex of ied. -

North American Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea): Redescription and Systematic Relationships of Tryonia Stimpson, 1865 and Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886

THE NAUTILUS 101(1):25-32, 1987 Page 25 . North American Hydrobiidae (Gastropoda: Rissoacea): Redescription and Systematic Relationships of Tryonia Stimpson, 1865 and Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886 Robert Hershler Fred G. Thompson Department of Invertebrate Zoology Florida State Museum National Museum of Natural History University of Florida Smithsonian Institution Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Washington, DC 20560, USA ABSTRACT scribed) in the Southwest. Taylor (1966) placed Tryonia in the Littoridininae Taylor, 1966 on the basis of its Anatomical details are provided for the type species of Tryonia turreted shell and glandular penial lobes. It is clear from Stimpson, 1865, Pyrgulopsis Call and Pilsbry, 1886, Fonteli- cella Gregg and Taylor, 1965, and Microamnicola Gregg and the initial descriptions and subsequent studies illustrat- Taylor, 1965, in an effort to resolve the systematic relationships ing the penis (Russell, 1971: fig. 4; Taylor, 1983:16-25) of these taxa, which represent most of the generic-level groups that Fontelicella and its subgenera, Natricola Gregg and of Hydrobiidae in southwestern North America. Based on these Taylor, 1965 and Microamnicola Gregg and Taylor, 1965 and other data presented either herein or in the literature, belong to the Nymphophilinae Taylor, 1966 (see Hyalopyrgus Thompson, 1968 is assigned to Tryonia; and Thompson, 1979). While the type species of Pyrgulop- Fontelicella, Microamnicola, Nat ricola Gregg and Taylor, 1965, sis, P. nevadensis (Stearns, 1883), has not received an- Marstonia F. C. Baker, 1926, and Mexistiobia Hershler, 1985 atomical study, the penes of several eastern species have are allocated to Pyrgulopsis. been examined by Thompson (1977), who suggested that The ranges of both Tryonia and Pyrgulopsis include parts the genus may be a nymphophiline. -

Developing Husbandry Methods to Produce a Reproductively Viable

Chronicles of Ex Situ Springsnail Management at Phoenix Zoo's Conservation Center Stuart A. Wells, Phoenix Zoo Conservation and Science Department [email protected] Summary The Phoenix Zoo’s Arthur L. and Elaine V. Johnson Foundation Conservation Center (Johnson Center) is the hub of our local species conservation involvement. We work closely Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD) and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) to assist with species conservation. Our conservation mission is to support field conservation by developing husbandry techniques and propagation for release protocols for species to be released back into their natural habitat. We are by AGFD and USFWS to work with them on the conservation of threatened and endangered species such as the desert pupfish, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, Mt. Graham red squirrel, black-footed ferret and the recently listed narrow-headed gartersnake. In 2004, a sudden dramatic reduction in the range of the Three Forks springsnail started discussions about creating a refugium as a hedge against extinction. In 2008, representatives from AGFD and USFWS asked the Zoo to collaborate on this project due to our historical involvement with native species conservation. Very little was known about the conditions necessary for sustained ex situ management and reproduction of hydrobiids. It was not clear if they could be maintained long-term nor whether they would be able to reproduce, and there was no record of this species ever reproducing outside of its natural habitat. In this paper, we chronicle the milestones, lessons learned and successes achieved while developing a consistent and reliable method of maintaining springsnail species ex situ. -

New Freshwater Snails of the Genus Pyrgulopsis (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae) from California

THE VELIGER CMS, Inc., 1995 The Veliger 38(4):343-373 (October 2, 1995) New Freshwater Snails of the Genus Pyrgulopsis (Rissooidea: Hydrobiidae) from California by ROBERT HERSHLER Department of Invertebrate Zoology (Mollusks), National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. 20560, USA Abstract. Seven new species of Recent springsnails belonging to the large genus Pyrgulopsis are described from California. Pyrgulopsis diablensis sp. nov., known from a single site in the San Joaquin Valley, P. longae sp. nov., known from a single site in the Great Basin (Lahontan system), and P. taylori sp. nov., narrowly endemic in one south-central coastal drainage, are related to a group of previously known western species also having terminal and penial glands on the penis. Pyrgulopsis eremica sp. nov., from the Great Basin and other interior drainages in northeast California, and P. greggi sp. nov., narrowly endemic in the Upper Kern River basin, differ from all other described congeners in lacking penial glands, and are considered to be derived from a group of western species having a small distal lobe and weakly developed terminal gland. Pyrgulopsis gibba sp. nov., known from a few sites in extreme northeastern California (Great Basin), has a unique complement of penial ornament consisting of terminal gland, Dg3, and ventral gland. Pyrgulopsis ventricosa sp. nov., narrowly endemic in the Clear Lake basin, is related to two previously described California species also having a full complement of glands on the penis (Pg, Tg, Dgl-3) and an enlarged bursa copulatrix. INTRODUCTION in the literature (Hershler & Sada, 1987; Hershler, 1989; Hershler & Pratt, 1990). -

Species Status Assessment Report for Beaverpond Marstonia

Species Status Assessment Report For Beaverpond Marstonia (Marstonia castor) Marstonia castor. Photo by Fred Thompson Version 1.0 September 2017 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia 1 2 This document was prepared by Tamara Johnson (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Georgia Ecological Services Field Office) with assistance from Andreas Moshogianis, Marshall Williams and Erin Rivenbark with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southeast Regional Office, and Don Imm (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Georgia Ecological Services Field Office). Maps and GIS expertise were provided by Jose Barrios with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Southeast Regional Office. We appreciate Gerald Dinkins (Dinkins Biological Consulting), Paul Johnson (Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources), and Jason Wisniewski (Georgia Department of Natural Resources) for providing peer review of a prior draft of this report. 3 Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2017. Species status assessment report for beaverpond marstonia. Version 1.0. September, 2017. Atlanta, GA. 24 pp. 4 Species Status Assessment Report for Beaverpond Marstonia (Marstonia castor) Prepared by the Georgia Ecological Services Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This species status assessment is a comprehensive biological status review by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) for beaverpond marstonia (Marstonia castor), and provides a thorough account of the species’ overall viability and extinction risk. Beaverpond marstonia is a small spring snail found in tributaries located east of Lake Blackshear in Crisp, Worth, and Dougherty Counties, Georgia. It was last documented in 2000. Based on the results of repeated surveys by qualified species experts, there appears to be no extant populations of beaverpond marstonia. -

Redescription of Marstonia Comalensis (Pilsbry & Ferriss, 1906), a Poorly Known and Possibly Threatened Freshwater Gastropod from the Edwards Plateau Region (Texas)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys Redescription77: 1–16 (2011) of Marstonia comalensis (Pilsbry & Ferriss, 1906), a poorly known and... 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.77.935 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Redescription of Marstonia comalensis (Pilsbry & Ferriss, 1906), a poorly known and possibly threatened freshwater gastropod from the Edwards Plateau region (Texas) Robert Hershler1, Hsiu-Ping Liu2 1 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, D.C. 20013- 7012, USA 2 Department of Biology, Metropolitan State College of Denver, Denver, CO 80217, USA Corresponding author : Robert Hershler ( [email protected] ) Academic editor: Anatoly Schileyko | Received 2 June 2010 | Accepted 13 January 2011 | Published 26 January 2011 Citation: Hershler R, Liu H-P (2011) Redescription of Marstonia comalensis (Pilsbry & Ferriss, 1906), a poorly known and possibly threatened freshwater gastropod from the Edwards Plateau region (Texas). ZooKeys 77 : 1 – 16 . doi: 10.3897/ zookeys.77.935 Abstract Marstonia comalensis, a poorly known nymphophiline gastropod (originally described from Comal Creek, Texas) that has often been confused with Cincinnatia integra, is re-described and the generic placement of this species, which was recently allocated to Marstonia based on unpublished evidence, is confi rmed by anatomical study. Marstonia comalensis is a large congener having an ovate-conic, openly umbilicate shell and penis having a short fi lament and oblique, squarish lobe bearing a narrow gland along its distal edge. It is well diff erentiated morphologically from congeners having similar shells and penes and is also geneti- cally divergent relative to those congeners that have been sequenced (mtCOI divergence 3.0–8.5%). -

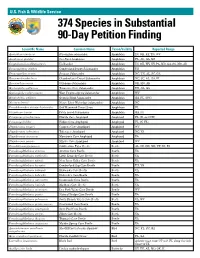

374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service 374 Species in Substantial 90-Day Petition Finding Scientific Name Common Name Taxon/Validity Reported Range Ambystoma barbouri Streamside salamander Amphibian IN, OH, KY, TN, WV Amphiuma pholeter One-Toed Amphiuma Amphibian FL, AL, GA, MS Cryptobranchus alleganiensis Hellbender Amphibian IN, OH, WV, NY, PA, MD, GA, SC, MO, AR Desmognathus abditus Cumberland Dusky Salamander Amphibian TN Desmognathus aeneus Seepage Salamander Amphibian NC, TN, AL, SC, GA Eurycea chamberlaini Chamberlain's Dwarf Salamander Amphibian NC, SC, AL, GA, FL Eurycea tynerensis Oklahoma Salamander Amphibian OK, MO, AR Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander Amphibian TN, AL, GA Gyrinophilus subterraneus West Virginia Spring Salamander Amphibian WV Haideotriton wallacei Georgia Blind Salamander Amphibian GA, FL (NW) Necturus lewisi Neuse River Waterdog (salamander) Amphibian NC Pseudobranchus striatus lustricolus Gulf Hammock Dwarf Siren Amphibian FL Urspelerpes brucei Patch-nosed Salamander Amphibian GA, SC Crangonyx grandimanus Florida Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. and NW) Crangonyx hobbsi Hobb's Cave Amphipod Amphipod FL (N. FL) Stygobromus cooperi Cooper's Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Stygobromus indentatus Tidewater Amphipod Amphipod NC, VA Stygobromus morrisoni Morrison's Cave Amphipod Amphipod VA Stygobromus parvus Minute Cave Amphipod Amphipod WV Cicindela marginipennis Cobblestone Tiger Beetle Beetle AL, IN, OH, NH, VT, NJ, PA Pseudanophthalmus avernus Avernus Cave Beetle Beetle VA Pseudanophthalmus cordicollis Little -

Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Findings on Petitions To

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 12/29/2017 and available online at https://federalregiste r.gov/d/2017-28163, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [4500090022] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Findings on Petitions to List a Species and Remove a Species from the Federal Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of 12-month petition findings. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), announce 12-month findings on petitions to list a species as an endangered or threatened species and remove a species from the Federal Lists of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants (List or Lists) under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). After a thorough review of the best available scientific and commercial information, we find that it is not warranted at this time to add the beaverpond marstonia to the Lists or remove the southwestern willow flycatcher from the List. However, we ask the public to submit to us at any time any new information that becomes available relevant to the status of either of the species listed above or their habitats. DATES: The findings in this document were made on [INSERT DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. ADDRESSES: Detailed descriptions of the basis for each of these findings are available on the Internet at http://www.regulations.gov under the following docket numbers: Species Docket Number Beaverpond marstonia FWS–R4–ES–2017–0090 1 Southwestern willow flycatcher FWS–R2–ES–2016–0039 Supporting information used to prepare these findings is available for public inspection, by appointment, during normal business hours, by contacting the appropriate person, as specified under FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT. -

Version 2020-04-20 Bear Lake Springsnail (Pyrgulopsis Pilsbryana

Version 2020-04-20 Bear Lake Springsnail (Pyrgulopsis pilsbryana) Species Status Statement. Distribution Bear Lake springsnail is known from three springs in the Bear River drainage in Rich County, Utah. Recently it has been suggested (Liu et al. 2017) that Ninemile pyrg (Pyrgulopsis nonaria) and southern Bonneville pyrg (Pyrgulopsis transversa) be synonymized with Bear Lake springsnail based on a lack of genetic difference between the three species, but additional research on genetics, morphology, and distribution of these three species and the other Pyrgulopsis in the region are needed to fully understand whether these three species should be collectively called Bear Lake springsnail. Table 1. Utah counties currently occupied by this species. Bear Lake Springsnail RICH Abundance and Trends The last inventory of Bear Lake springsnail happened over 20 years ago, and a quantitative assessment of the species abundance is not available (Hershler 1995). Recent taxonomic research indicates a need for a comprehensive status assessment of Pyrgulopsis in north-central Utah. Statement of Habitat Needs and Threats to the Species. Habitat Needs Bear Lake springsnail occurs in relatively small, mineralized, spring-fed water bodies. Individuals are commonly found on or between aquatic vegetation, bedrock, or pieces of travertine (Hershler 1998). They tend to congregate near the head of springs, where conditions are presumably more stable in comparison to downstream locations (Hershler 1998). Threats to the Species Given recent taxonomic revision, managers need to complete a new threat assessment for this species. In general, however, the localized distribution of this snail makes the species susceptible to catastrophic natural events, or human actions, that could destroy or degrade Version 2020-04-20 the spring habitats where it lives. -

Springsnails (Gastropoda, Hydrobiidae) of Owens and Amargosa River California-Nevada

Springsnails (Gastropoda, Hydrobiidae) Of Owens And Amargosa River California-Nevada R Hershler Proceedings of The Biological Society of Washington 102:176-248 (1989) http://biostor.org/reference/74590 Page images from the Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/, made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/ PROC. BtOL SOC. WASH. 102(t). t989, pp. 176-248 SPRINGSNAILS (GASTROPODA: HYDROBIIDAE) OF OWENS AND AMARGOSA RIVER (EXCLUSIVE OF ASH MEADOWS) DRAINAGES, DEATH VALLEY SYSTEM, CALIFORNIA-NEVADA Robert Hershler Abstract. - Thirteen springsnail species (9 new) belonging to Pyrgulopsis Call & Pilsbry, 1886, and Tryonia Stimpson, 1865 aTe recorded from the region encompassing pluvial Owens and Amargosa River (exclusive of Ash Meadows) drainages in southeastern California and southwestern Nevada. Discriminant analyses utilizing shell morphometric data confirmed distinctiveness of the nine new species described herein, as: Pyrgulopsis aardahli, P. amargosae, P. olVenensis, P. perlubala, P. wongi, Tyronia margae, T. robusla, T. rowlandsi, and 1: salina. Of the 22 springsnails known from Death Valley System, 17 have very localized distributi ons, with endemic fauna concentrated in Owens Valley, Death Valley, and Ash Meadows. A preliminary analysis showed only partial correlation betwecn modern springs nail zoogeography and configuration of inter·connected Pleistocene lakes comprising the Death Valley System. This constitutes the second part of a sys List of Recognized Taxa tematic treatment of springsnails from the Pyrgu/opsis aardah/i, new species. Death Valley System, a large desert region P. amargosac. new species. in southeastern California and southwest P. micrococcus (Pilsbry. 1893). ern Nevada integrated by a se ries of la kes P. -

2020 Biological Assessment for the Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program in New Mexico

2020 Biological Assessment For the Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program in New Mexico 01/24/2020 Prepared by USDA, APHIS, PPQ 270 South 17th Street Las Cruces, NM 88005 BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT (BA) FOR STATE CONSULTATION AND CONFERENCE FOR 2020 GH/MC PROGRAMS IN NEW MEXICO 2020 Biological Assessment for the Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program, New Mexico 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), in conjunction with other Federal agencies, State departments of agriculture, land management groups, and private individuals, is planning to conduct grasshopper control programs in New Mexico in 2020. This document is intended as state-wide consultation and conference with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) regarding the APHIS Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program. Beginning in 1987, APHIS has consulted with the FWS on a national level for the Rangeland Grasshopper Cooperative Management Program. Biological Opinions (BO) were issued annually by FWS from 1987 through 1995 for the national program. A letter dated October 3, 1995 from FWS to APHIS concurred with buffers and other measures agreed to by APHIS for New Mexico and superseded all previous consultations. Since then, funding constraints and other considerations have drastically reduced grasshopper/Mormon cricket suppression activities. APHIS is requesting initiation of informal consultation for the implementation of the 2020 Rangeland Grasshopper and Mormon Cricket Suppression Program on rangeland in New Mexico. Our determinations of effect for listed species, proposed candidate species, critical habitat, and proposed critical habitat are based on the October 3, 1995 FWS letter, the analysis provided in the 2019 Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for APHIS suppression activities in 17 western states, and local discussions with FWS. -

Mitochondrial DNA Hyperdiversity and Population Genetics in the Periwinkle Melarhaphe Neritoides (Mollusca: Gastropoda)

Mitochondrial DNA hyperdiversity and population genetics in the periwinkle Melarhaphe neritoides (Mollusca: Gastropoda) Séverine Fourdrilis Université Libre de Bruxelles | Faculty of Sciences Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences | Directorate Taxonomy & Phylogeny Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor (PhD) in Sciences, Biology Date of the public viva: 28 June 2017 © 2017 Fourdrilis S. ISBN: The research presented in this thesis was conducted at the Directorate Taxonomy and Phylogeny of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS), and in the Evolutionary Ecology Group of the Free University of Brussels (ULB), Brussels, Belgium. This research was funded by the Belgian federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO Action 1 MO/36/027). It was conducted in the context of the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) research community ‘‘Belgian Network for DNA barcoding’’ (W0.009.11N) and the Joint Experimental Molecular Unit at the RBINS. Please refer to this work as: Fourdrilis S (2017) Mitochondrial DNA hyperdiversity and population genetics in the periwinkle Melarhaphe neritoides (Linnaeus, 1758) (Mollusca: Gastropoda). PhD thesis, Free University of Brussels. ii PROMOTERS Prof. Dr. Thierry Backeljau (90 %, RBINS and University of Antwerp) Prof. Dr. Patrick Mardulyn (10 %, Free University of Brussels) EXAMINATION COMMITTEE Prof. Dr. Thierry Backeljau (RBINS and University of Antwerp) Prof. Dr. Sofie Derycke (RBINS and Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Jean-François Flot (Free University of Brussels) Prof. Dr. Marc Kochzius (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) Prof. Dr. Patrick Mardulyn (Free University of Brussels) Prof. Dr. Nausicaa Noret (Free University of Brussels) iii Acknowledgements Let’s be sincere. PhD is like heaven! You savour each morning this taste of paradise, going at work to work on your passion, science.