Vegetation Ecology and Change in Terrestrial Ecosystems 35

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbines School of Botanical Studies Wild Food Tending Economic Botanical Survey Trip #9: North Umpqua Watershed

Columbines School of Botanical Studies Wild Food Tending Economic Botanical Survey Trip #9: North Umpqua Watershed August 8-9, 2019 Abundance Phenology d – dominant (defines the plant community) L - In Leaf a - abundant (codominant of the overstory or dominant of lower layer) FL - In Flower c – common (easily seen) FR - In Fruit o – occasional (walk around to see) SN - Senescent r – rare (trace, must search for it) Uses Genus Name Notes Abundance Phenology Food: Roots Brodiaea sp. incl Dichelostemma Brodiaea sp., Triteleia sp. Camassia leichtlinii Great Camas a FR-SN Camassia quamash ssp. intermedia Camas c FR-SN Camassia sp. Common Camas Cirsium vulgare Bull Thistle Daucus carota Wild Carrot a Hypochaeris radicata False Dandelion Lilium sp. Lily Osmorhiza berteroi (O. chilensis) Sweet Cicely Perideridia howellii Yampah Perideridia montana (P. gairdneri) Late Yampah c FL Taraxacum officinalis Dandelion r FL Typha latifolia Cattail FL Food: Greens and Potherbs Berberis aquifolium Tall Oregon Grape Berberis nervosa Oregon Grape Castilleja miniata Paintbrush cf. Potentilla sp. Potentilla Chamaenerion angustifolium Fireweed (Epilobium a.) Cirsium vulgare Bull Thistle Daucus carota Wild Carrot a Erythranthe guttata (Mimulus g.) Yellow Monkeyflower Fragaria sp. Wild Strawberry Gallium sp. Bedstraw, Cleavers Hypochaeris radicata False Dandelion Columbines School of Botanical Studies Wild Food Tending Economic Botanical Survey Trip #9: North Umpqua Watershed Uses Genus Name Notes Abundance Phenology Leucanthemum vulgare Ox Eye Daisy c FL (Chrysanthemum l.) Osmorhiza berteroi (O. chilensis) Sweet Cicely Perideridia howellii Yampah Perideridia montana (P. gairdneri) Late Yampah c FL Plantago lanceolata Plantain Prunella vulgaris Self Heal, Heal All Rosa sp. Wild Rose Rubus ursinus Blackberry Rumex obtusifolius Bitter Dock Sidalcea sp. -

State Natural Area Management Plan

OLD FOREST STATE NATURAL AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN STATE OF TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION NATURAL AREAS PROGRAM APRIL 2015 Prepared by: Allan J. Trently West Tennessee Stewardship Ecologist Natural Areas Program Division of Natural Areas Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 2nd Floor Nashville, TN 37243 TABLE OF CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 1 A. Guiding Principles .................................................................................................. 1 B. Significance............................................................................................................. 1 C. Management Authority ........................................................................................... 2 II DESCRIPTION ........................................................................................................... 3 A. Statutes, Rules, and Regulations ............................................................................. 3 B. Project History Summary ........................................................................................ 3 C. Natural Resource Assessment ................................................................................. 3 1. Description of the Area ....................................................................... 3 2. Description of Threats ....................................................................... -

Illinois Native Plant Society 2019 Plant List Herbaceous Plants

Illinois Native Plant Society 2019 Plant List Plant Sale: Saturday, May 11, 9:00am – 1:00pm Illinois State Fairgrounds Commodity Pavilion (Across from Grandstand) Herbaceous Plants Scientific Name Common Name Description Growing Conditions Comment Dry to moist, Sun to part Blooms mid-late summer Butterfly, bee. Agastache foeniculum Anise Hyssop 2-4', Lavender to purple flowers shade AKA Blue Giant Hyssop Allium cernuum var. Moist to dry, Sun to part Nodding Onion 12-18", Showy white flowers Blooms mid summer Bee. Mammals avoid cernuum shade 18", White flowers after leaves die Allium tricoccum Ramp (Wild Leek) Moist, Shade Blooms summer Bee. Edible back Moist to dry, Part shade to Blooms late spring-early summer Aquilegia canadensis Red Columbine 30", Scarlet and yellow flowers shade Hummingbird, bee Moist to wet, Part to full Blooms late spring-early summer Showy red Arisaema dracontium Green Dragon 1-3', Narrow greenish spadix shade fruits. Mammals avoid 1-2', Green-purple spadix, striped Moist to wet, Part to full Blooms mid-late spring Showy red fruits. Arisaema triphyllum Jack-in-the-Pulpit inside shade Mammals avoid Wet to moist, Part shade to Blooms late spring-early summer Bee. AKA Aruncus dioicus Goatsbeard 2-4', White fluffy panicles in spring shade Brides Feathers Wet to moist, Light to full Blooms mid-late spring Mammals avoid. Asarum canadense Canadian Wildginger 6-12", Purplish brown flowers shade Attractive groundcover 3-5', White flowers with Moist, Dappled sun to part Blooms summer Monarch larval food. Bee, Asclepias exaltata Poke Milkweed purple/green tint shade butterfly. Uncommon Blooms mid-late summer Monarch larval Asclepias hirtella (Tall) Green Milkweed To 3', Showy white flowers Dry to moist, Sun food. -

ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW DRAFT #2 Colorado National Monument Sally Mcbeth February 26, 2010

ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW DRAFT #2 Colorado National Monument Sally McBeth February 26, 2010 written in consultation with the Northern Ute ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW DRAFT #2 Colorado National Monument Sally McBeth February 26, 2010 written in consultation with the Northern Ute Submitted to the National Park Service Cooperative Agreement # H1200040001 (phases I and II) and H1200090004 (phase III) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The generosity of many Ute friends, whose willingness to share their stories, remembrances, and recollections with me cannot go unacknowledged. I treasure their rich and profound understandings of ancestral landscape shared with me over the past three years. These friends include, but are not limited to Northern Ute tribal members (alphabetically): Loya Arrum, Betsy Chapoose, Clifford Duncan, Kessley LaRose, Roland McCook, Venita Taveapont, and Helen Wash. Their advice and suggestions on the writing of this final report were invaluable. Special thanks are due to Hank Schoch—without whose help I really would not have been able to complete (or even start) this project. His unflagging generosity in introducing me to the refulgent beauty and cultural complexity of Colorado National Monument cannot ever be adequately acknowledged. I treasure the memories of our hikes and ensuing discussions on politics, religion, and life. The critical readings by my friends and colleagues, Sally Crum (USFS), Dave Fishell (Museum of the West), Dave Price (NPS), Hank Schoch (NPS-COLM), Alan McBeth, and Mark Stevens were very valuable. Likewise the advice and comments of federal-level NPS staff Cyd Martin, Dave Ruppert, and especially Tara Travis were invaluable. Thanks, all of you. Former Colorado National Monument Superintendant Bruce Noble and Superintendant Joan Anzelmo provided tremendous support throughout the duration of the project. -

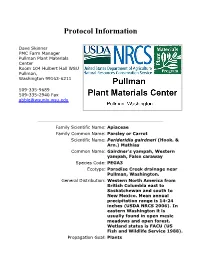

Protocol Information

Protocol Information Dave Skinner PMC Farm Manager Pullman Plant Materials Center Room 104 Hulbert Hall WSU Pullman, Washington 99163-6211 509-335-9689 509-335-2940 Fax [email protected] Family Scientific Name: Apiaceae Family Common Name: Parsley or Carrot Scientific Name: Perideridia gairdneri (Hook. & Arn.) Mathias Common Name: Gairdner's yampah, Western yampah, False caraway Species Code: PEGA3 Ecotype: Paradise Creek drainage near Pullman, Washington. General Distribution: Western North America from British Columbia east to Saskatchewan and south to New Mexico. Mean annual precipitation range is 14-24 inches (USDA NRCS 2006). In eastern Washington it is usually found in open mesic meadows and open forest. Wetland status is FACU (US Fish and Wildlife Service 1988). Propagation Goal: Plants Propagation Method: Seed Product Type: Container (plug) Time To Grow: 2 Years Propagule Collection: Fruit is a schizocarp. Seed is collected in September or early October when the inflorescence is dry and the seeds are brown in color. Seed can be stripped from the inflorescence or the entire inflorescence can be clipped from the plant. Harvested seed is stored in paper bags at room temperature until cleaned. 400,000 seeds/lb (USDA NRCS 2006). Propagule Processing: The inflorescence is rubbed by hand to free the seed, then cleaned with an air column separator. Clean seed is stored in controlled conditions at 40 degrees Fahrenheit and 40% relative humidity. Pre-Planting Treatments: Unpublished data from trials conducted at the Pullman Plant Materials Center revealed that no germination occurred without stratification or with 30 days stratification. 60 days of cold, moist stratification resulted in 38% germination. -

DATA by CLASSIFICATION Page Land & Water Acreage Leased

State of Illinois Illinois Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Report Report Cover Table of Contents Land & Water Leased Water DATA BY CLASSIFICATION Page Acreage Acreage Acreage* Pictured on the cover is Wise Ridge Bedrock Hill State Natural Area. Located in the State Parks 4 127,793.172 9,911.280 10,481.640 Shawnee Hills in Johnson County, this property is listed in the Illinois Natural Area Inventory for its high quality forest and limestone glades. More than a mile of the Conservation Areas 10 73,275.608 0.000 20,402.326 Tunnel Hill State Trail runs through this tract providing good public access. Fish Facilities 12 232.650 32.500 60.100 Natural Areas 13 44,631.941 0.000 3,869.200 Acquisition of this 555.845+/- acre tract allows IDNR to preserve a scenic, forested Fish and Wildlife Areas 26 94,542.623 73,384.180 8,627.290 corridor along the Tunnel Hill Trail consistent with statewide conservation and natural State Wildlife Areas 30 1,356.193 700.000 0.000 resource plans. Wise Ridge is in the Eastern Shawnee Conservation Opportunity Area Greenways and Trails 30 1,560.342 0.000 0.000 of Illinois Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Plan. The property is a mixture of State Memorials 31 0.100 0.000 0.000 steep, forested slopes, limestone barrens and a bottomland bordering Pond Creek, a Boating Access Areas 31 6.300 304.300 0.000 tributary of the South Fork of the Saline River. Expanded public recreational State Recreation Areas 31 3,955.015 9,300.000 16.800 opportunities will include hunting, wildlife observation and hiking trails. -

Loch Lomond Button-Celery)

Natural Diversity Data Base 2003). The Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge populations have been monitored annually since 1992 (J. Silveira in litt. 2000). One additional occurrence of C. hooveri in Merced County is on private land (the Bert Crane Ranch) that is protected from development by a conservation easement (J. Silveira in litt. 2000). We funded a status survey for Chamaesyce hooveri and other vernal pool plants in 1986 and 1987 (Stone et al. 1988), resulting in 10 new occurrences. We and the California Department of Fish and Game jointly funded an ecological study of the Vina Plains Preserve pools, which was conducted by faculty from California State University, Chico (Alexander and Schlising 1997). Independent surveys conducted by Joseph Silveira led to discovery of the Merced and Glenn county occurrences (J. Silveira in litt. 2000). Private landowners also have contributed to conservation of this species. One pool in Tehama County was fenced by the property owner in the late 1980s, to exclude livestock (Stone et al. 1988). 3. ERYNGIUM CONSTANCEI (LOCH LOMOND BUTTON-CELERY) a. Description and Taxonomy Taxonomy.—Loch Lomond button-celery, specifically known as Eryngium constancei (Sheikh 1983), is a member of the carrot family (Apiaceae). This species was only recently described and therefore has no history of name changes. The common name was derived from the type locality, Loch Lomond, which is in Lake County (Sheikh 1983). Other common names for this species are Loch Lomond coyote-thistle (Skinner and Pavlik 1994) and Constance’s coyote-thistle (Smith et al. 1980). Description and Identification.—Certain features are common to species of the genus Eryngium. -

1 Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Minutes of the 206

Illinois Nature Preserves Commission Minutes of the 206th Meeting (Approved at the 207th Meeting) Burpee Museum of Natural History 737 North Main Street Rockford, IL 61103 Tuesday, September 21, 2010 206-1) Call to Order, Roll Call, and Introduction of Attendees At 10:05 a.m., pursuant to the Call to Order of Chair Riddell, the meeting began. Deborah Stone read the roll call. Members present: George Covington, Donnie Dann, Ronald Flemal, Richard Keating, William McClain, Jill Riddell, and Lauren Rosenthal. Members absent: Mare Payne and David Thomas. Chair Riddell stated that the Governor has appointed the following Commissioners: George M. Covington (replacing Harry Drucker), Donald (Donnie) R. Dann (replacing Bruce Ross- Shannon), William E. McClain (replacing Jill Allread), and Dr. David L. Thomas (replacing John Schwegman). It was moved by Rosenthal, seconded by Flemal, and carried that the following resolution be approved: The Illinois Nature Preserves Commission wishes to recognize the contributions of Jill Allread during her tenure as a Commissioner from 2000 to 2010. Jill served with distinction as Chair of the Commission from 2002 to 2004. She will be remembered for her clear sense of direction, her problem solving abilities, and her leadership in taking the Commission’s message to the broader public. Her years of service with the Commission and her continuing commitment to and advocacy for the Commission will always be greatly appreciated. (Resolution 2089) It was moved by Rosenthal, seconded by Flemal, and carried that the following resolution be approved: The Illinois Nature Preserves Commission wishes to recognize the contributions of Harry Drucker during his tenure as a Commissioner from 2001 to 2010. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

The Grand Prairie

A PUBLICATION OF OPENLANDS VOLUME 26–No. 1, SPRING/SUMMER 2021 The Grand Prairie There are very few written accounts of the Grand Prairie from which Illinois gets its nickname, “The Prairie State,” and even fewer in art. An elusive landscape to most 19 th century artists, prairies lacked the traditional composition elements artists relied on at the time, such as trees to frame the foreground or mountains in the background. The artists moved on to capture the Rockies, Yosemite, and the great American West. In 1820, Illinois had 22 million acres of prairie, roughly two thirds of the state. By 1900, most of Illinois‘ prairies were gone. The movement of four glaciers gave rise to the prairie ecosystems of Illinois. of motivated individuals and nonprofit and governmental organizations, even When early settlers discovered the prairie’s rich soil, they quickly converted a those fragments would be gone. majority of the state to farmland. Through the bounty of nature, Chicago — Philip Juras, Picturing the Prairie: A Vision of Restoration became a great metropolis. By 1978, fewer than 2,300 acres — roughly three and a half square miles—of original prairie remained in the entire state. Goose Lake Prairie is the largest remnant tallgrass prairie east of the Mississippi Of those undisturbed prairie sites, known as remnant prairie, most are along River. Like much of the original prairie in the state, Goose Lake Prairie was sculpted railroad rights-of-way, in pioneer-era cemeteries, and in places that were not by glaciers. The area was part of a continuous grassland that stretched from suitable for farming. -

Developing Biogeographically Based Population Introduction Protocols for At-Risk Plant Species of the Interior Valleys of Southwestern Oregon

Developing biogeographically based population introduction protocols for at-risk plant species of the interior valleys of southwestern Oregon: Fritillaria gentneri (Gentner’s fritillary) Limnanthes floccosa ssp. bellingeriana (Bellinger’s meadowfoam) Limnanthes floccosa ssp. grandiflora (big-flowered wooly meadowfoam) Limnanthes floccosa ssp. pumila (dwarf wooly meadowfoam) Limnanthes gracilis var. gracilis (slender meadowfoam) Lomatium cookii (Cook’s desert parsley) Perideridia erythrorhiza (red-rooted yampah) Plagiobothrys hirtus (rough popcorn flower) Ranunculus austro-oreganus (southern Oregon buttercup) Prepared by Rebecca Currin, Kelly Amsberry, and Robert J. Meinke Native Plant Conservation Program, Oregon Department of Agriculture for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Grant OR-EP-2, segment 14) Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the many people who contributed to the completion of this report. Thanks to Andy Robinson and Kathy Pendergrass (USFWS) for providing funding and encouragement (Grant no. OR-EP-2, segment 14). R.J. Meinke contributed to text completion and review, and Melissa Carr provided invaluable assistance in compiling data. Thanks also to the staff, interns and students who provided plant and habitat photos. Contact Information: Robert J. Meinke Kelly Amsberry Native Plant Conservation Program Native Plant Conservation Program Oregon Department of Agriculture Oregon Department of Agriculture Dept. of Botany and Plant Pathology Dept. of Botany and Plant Pathology Oregon State University Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 97331 Corvallis, OR 97331 (541) 737-2317 (541) 737-4333 [email protected] [email protected] Report format: The following species are presented in alphabetical order: Fritillaria gentneri (Gentner’s fritillary), Limnanthes floccosa ssp. bellingeriana (Bellinger’s meadowfoam), Limnanthes floccosa ssp. grandiflora (big-flowered wooly meadowfoam), Limnanthes floccosa ssp. -

Inventory of Select Groups of Arthropods of Four Mason County Nature Preserves

I L L I N 0 I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Natural History Suvey /91 Libmry mc77 (?}Ifj0 Inventory of select groups of arthropods of four Mason County nature preserves carried out by members of the Illinois Natural History Survey Center for Biodiversity 607 E. Peabody Champaign, Illinois 61820-6970 Annual report for the 1997-98 fiscal year of the Multi-State Prairie Insect Inventory to Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and United States Fish and Wildlife Service Illinois Natural History Survey Technical Report 1998 (19) Prepared by: Chris Dietrich Kathy Methven David Voegtlin Submitted: September 1998 Inventory of Selected Groups of Arthropods of Four Nature Preserves in Mason Co., Illinois. July 1997- June 1998. Introduction Sampling for prairie arthropods for fiscal 1997-98 focused on four nature preserves in Mason Co., Illinois: Long Branch Sand Prairie, Matanzas Prairie, Sand Prairie - Scrub Oak Nature Preserve, and Revis Hill Prairie. Long Branch comprises 93 acres of sand prairie dominated by prickly pear, Opuntia compressa, and the grasses Eragrostistrichodes, Schizachyrium scoparium, and Calamovilfa longifolia, and is typical of the Illinois River Sand Areas. Management has been largely restricted to the cutting of planted pine trees and limited burning. Sampling was conducted in a restored area near the south end that was burned in Spring 1997 and and extensive unburned native prairie at the north end of the preserve. Matanzas Prairie is a high quality wet prairie comprising 27.6 acres and dominated by Calamagrostiscanadensis, Spartina pectinata, and Andropogon gerardii.