Ethnohistorical Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Columbines School of Botanical Studies Wild Food Tending Economic Botanical Survey Trip #9: North Umpqua Watershed

Columbines School of Botanical Studies Wild Food Tending Economic Botanical Survey Trip #9: North Umpqua Watershed August 8-9, 2019 Abundance Phenology d – dominant (defines the plant community) L - In Leaf a - abundant (codominant of the overstory or dominant of lower layer) FL - In Flower c – common (easily seen) FR - In Fruit o – occasional (walk around to see) SN - Senescent r – rare (trace, must search for it) Uses Genus Name Notes Abundance Phenology Food: Roots Brodiaea sp. incl Dichelostemma Brodiaea sp., Triteleia sp. Camassia leichtlinii Great Camas a FR-SN Camassia quamash ssp. intermedia Camas c FR-SN Camassia sp. Common Camas Cirsium vulgare Bull Thistle Daucus carota Wild Carrot a Hypochaeris radicata False Dandelion Lilium sp. Lily Osmorhiza berteroi (O. chilensis) Sweet Cicely Perideridia howellii Yampah Perideridia montana (P. gairdneri) Late Yampah c FL Taraxacum officinalis Dandelion r FL Typha latifolia Cattail FL Food: Greens and Potherbs Berberis aquifolium Tall Oregon Grape Berberis nervosa Oregon Grape Castilleja miniata Paintbrush cf. Potentilla sp. Potentilla Chamaenerion angustifolium Fireweed (Epilobium a.) Cirsium vulgare Bull Thistle Daucus carota Wild Carrot a Erythranthe guttata (Mimulus g.) Yellow Monkeyflower Fragaria sp. Wild Strawberry Gallium sp. Bedstraw, Cleavers Hypochaeris radicata False Dandelion Columbines School of Botanical Studies Wild Food Tending Economic Botanical Survey Trip #9: North Umpqua Watershed Uses Genus Name Notes Abundance Phenology Leucanthemum vulgare Ox Eye Daisy c FL (Chrysanthemum l.) Osmorhiza berteroi (O. chilensis) Sweet Cicely Perideridia howellii Yampah Perideridia montana (P. gairdneri) Late Yampah c FL Plantago lanceolata Plantain Prunella vulgaris Self Heal, Heal All Rosa sp. Wild Rose Rubus ursinus Blackberry Rumex obtusifolius Bitter Dock Sidalcea sp. -

Journal of the Western Slope

JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN SLOPE VO LUME II. NUMBER 1 WINTER 1996 ~,. ~. I "Queen" Chipeta-page I Audre Lucile Ball : Her Life in the Grand Valley From World War 1I Through Ihe Fifties-page 23 JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN SLOPE is published quarterly by two student organizations at Mesa State College: the Mesa State College Historical Society and the Alpha-Gamma-Epsilon Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta. Annual subscriptions are $14. (Single copies are available by contacting the editors of the Journal.) Retailers are en couraged to write for prices. Address subscriptions and orders for back issues to: Mesa State College Journal of the Western Slope P.O. Box 2647 Grand Junction, CO 81502 GUIDELINES FOR CONTRIBUTORS: The pu'pOSfI 01 THE X>URNAl OF THE WESTERN SlOf'E is 10 I!flCOUrIIge tdloIarly sl\l(!y 01 CoIorIIdD'$ Western Slope. The primary goat is to pre5erve !loci leeonl its hislory; IIowewI. IttideS on anlhlopology', economics, govemmelli. naltJfal histOtY. arod SOCiology will be considered. Author$hlP is open 10 anyomt who wishel to svbmiI original and 5dloIarly malerialliboullhe WMteln Slope. The ed~OtS encourage teners oIlnq~ .rom prOSp8CIlYG authors. 5eI'Id matMiahs lind IellafS 10 THE JOURNAL Of THE WESTERN SLOPE, MeS<! State College. P.O. Box 26<&7. Grand June tion,C081502, I ) ConlrlbulOfS are requasled 10 senCIltleir mallUscript on an IBM-compalibla disk. DO NOT SEND THE ORIGINAL. Editol1l will not retlJm disl\s, Matarial snoold be tootnoted. The editors will give preien,.... ce to submissions at about IMrnly·live pages. 2) AlkJw thtlll(!itol1l sixty days to review mar.uscripts. -

The Frontiers of American Grand Strategy: Settlers, Elites, and the Standing Army in America’S Indian Wars

THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Washington, D.C. August 11, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrew Alden Szarejko All Rights Reserved ii THE FRONTIERS OF AMERICAN GRAND STRATEGY: SETTLERS, ELITES, AND THE STANDING ARMY IN AMERICA’S INDIAN WARS Andrew Alden Szarejko, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrew O. Bennett, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Much work on U.S. grand strategy focuses on the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. If the United States did have a grand strategy before that, IR scholars often pay little attention to it, and when they do, they rarely agree on how best to characterize it. I show that federal political elites generally wanted to expand the territorial reach of the United States and its relative power, but they sought to expand while avoiding war with European powers and Native nations alike. I focus on U.S. wars with Native nations to show how domestic conditions created a disjuncture between the principles and practice of this grand strategy. Indeed, in many of America’s so- called Indian Wars, U.S. settlers were the ones to initiate conflict, and they eventually brought federal officials into wars that the elites would have preferred to avoid. I develop an explanation for settler success and failure in doing so. I focus on the ways that settlers’ two faits accomplis— the act of settling on disputed territory without authorization and the act of initiating violent conflict with Native nations—affected federal decision-making by putting pressure on speculators and local elites to lobby federal officials for military intervention, by causing federal officials to fear that settlers would create their own states or ally with foreign powers, and by eroding the credibility of U.S. -

The Colorado Magazine

THE COLORADO MAGAZINE Published by The State Historical and Natural History Society of Colorado Devoted to the Interests of the Society, Colorado, and the West Copyrighted 1924 by the State Historical and Natural History Society of Colorado. VOL. Denver, Colorado, November, 1924 NO. 7 Spanish Expeditions Into Colorado:f. By Alfred Barnaby Thomas, M. A., Berkeley, California. I. INTRODUCTION We customarily associate Spanish explorations in the West with New Mexico, with Texas, with Arizona, or with California, but not with Colorado. Yet Spaniards in the eighteenth century were well acquainted with large portions of the region now com prised in that state. Local historians of Colorado often err by pushing the clock too far back, and asserting that Coronado, Oriate, and other sixteenth century conquistadores entered the state. On the other hand, they fail to mention several important expeditions which at a later date did enter the confines of the state. An Outpost of New Mexico.-The Colorado region in Span ish days was a frontier of New Mexico. Santa Fe was the base for Colorado as San Agustin was for Georgia. Three interests especially spurred the New Mexicans to make long journeys northward to the Platte River, to the upper Arkansas in central Colorado, and to the Dolores, Uncomphagre, Gunnison, and Grand Rivers on the western borders. These interests were Indians, French intruders, and rumored mines. After 1673 reports of Frenchmen in the Pawnee country constantly worried officials at Santa Fe. Frequently tales of gold and sil'ver were wafted southward to sensitive Spanish ears at the New Mexico capital. -

Vegetation Ecology and Change in Terrestrial Ecosystems 35

Chapter 4—Vegetation Ecology and Change in Terrestrial Ecosystems 35 CHAPTER 4 Vegetation Ecology and Change in Terrestrial Ecosystems John B. Taft1, Roger C. Anderson2, and Louis R. Iverson3 with sidebar by William C. Handel1 1. Illinois Natural History Survey 2. Department of Biology, Illinois State University 3. USDA Forest Service OBJECTIVES What are the major vegetation types that have occurred in Illinois and how have they changed since the last ice age and more specifically since European-Americans settled the region? Ecological factors influencing trends, composition, and diversity in prairie, savanna, open woodland, and forest communities are examined. Historical and contemporary changes will be explored with reference to the proportion and characteristics of habitats remaining in a relatively undegraded condition. While Illinois is a focus for this chapter, the processes and factors explaining vegetational variation have relevance to the entire Midwest and in many cases beyond. INTRODUCTION key step in conserving biodiversity. The following chapter explores the dominant types of native terrestrial vegetation Vegetation change is a major focus of ecological monitoring and changes as they have occurred in Illinois primarily since and research and has both temporal and spatial aspects. Of Pleistocene glaciation with a focus on the post-European course, all change is measured through time. Change can settlement period. be evaluated on a time scale of thousands of years, such as following Pleistocene glaciation, or in the time frame of an In thE FOrMEr tIME annual species. An example of a spatial aspect of vegetation The last glacial episode, known as Wisconsinan glaciation, change is the emergence of forest where once prairie covered the northeastern quarter of Illinois from about occurred (see Fig. -

THREE SACRED VALLEYS): an Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S

Paitu Nanasuagaindu Pahonupi (THREE SACRED VALLEYS): An Assessment of Native American Cultural Resources Potentially Affected by Proposed U.S. Air Force Electronic Combat Test Capability Actions and Alternatives at the Utah Test and Training Range Item Type Report Authors Stoffle, Richard W.; Halmo, David; Olmsted, John Publisher Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan Download date 01/10/2021 12:00:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/271235 PAITU NANASUAGAINDU PAHONUPI(THREE SACRED VALLEYS): AN ASSESSMENT OF NATIVE AMERICAN CULTURAL RESOURCES POTENTIALLY AFFECTED BY PROPOSED U.S. AIR FORCE ELECTRONIC COMBAT TEST CAPABILITY ACTIONS AND ALTERNATIVES AT THE UTAH TEST AND TRAINING RANGE DRAFT INTERIM REPORT By Richard W. Stoffle David B. Halmo John E. Olmsted Institute for Social Research University of Michigan April 14, 1989 Submitted to: Science Applications International Corporation Las Vegas, Nevada TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 Description of Study Area 2 Description of Project 2 Site Specific Assessment 3 Tactical Threat Area 3 Threat Sites and Array 4 Range Maintenance Facilities 4 Programmatic Assessment 5 Airspace and Flight Activities Effects 5 Gapfiller Radar Site 5 Future Programmatic Assessments 5 Commercial Power 5 Fiber -optic Communications Network 5 Project - Related Structures and Activities on DOD lands 5 CHAPTER TWO ETHNOHISTORY OF INVOLVED NATIVE AMERICAN GROUPS 7 Ethnic Groups and Territories 7 Overview 7 Gosiutes 9 Pahvants 12 Utes 13 Early Contact, Euroamerican Colonization, -

ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW DRAFT #2 Colorado National Monument Sally Mcbeth February 26, 2010

ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW DRAFT #2 Colorado National Monument Sally McBeth February 26, 2010 written in consultation with the Northern Ute ETHNOGRAPHIC OVERVIEW DRAFT #2 Colorado National Monument Sally McBeth February 26, 2010 written in consultation with the Northern Ute Submitted to the National Park Service Cooperative Agreement # H1200040001 (phases I and II) and H1200090004 (phase III) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The generosity of many Ute friends, whose willingness to share their stories, remembrances, and recollections with me cannot go unacknowledged. I treasure their rich and profound understandings of ancestral landscape shared with me over the past three years. These friends include, but are not limited to Northern Ute tribal members (alphabetically): Loya Arrum, Betsy Chapoose, Clifford Duncan, Kessley LaRose, Roland McCook, Venita Taveapont, and Helen Wash. Their advice and suggestions on the writing of this final report were invaluable. Special thanks are due to Hank Schoch—without whose help I really would not have been able to complete (or even start) this project. His unflagging generosity in introducing me to the refulgent beauty and cultural complexity of Colorado National Monument cannot ever be adequately acknowledged. I treasure the memories of our hikes and ensuing discussions on politics, religion, and life. The critical readings by my friends and colleagues, Sally Crum (USFS), Dave Fishell (Museum of the West), Dave Price (NPS), Hank Schoch (NPS-COLM), Alan McBeth, and Mark Stevens were very valuable. Likewise the advice and comments of federal-level NPS staff Cyd Martin, Dave Ruppert, and especially Tara Travis were invaluable. Thanks, all of you. Former Colorado National Monument Superintendant Bruce Noble and Superintendant Joan Anzelmo provided tremendous support throughout the duration of the project. -

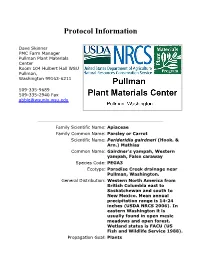

Protocol Information

Protocol Information Dave Skinner PMC Farm Manager Pullman Plant Materials Center Room 104 Hulbert Hall WSU Pullman, Washington 99163-6211 509-335-9689 509-335-2940 Fax [email protected] Family Scientific Name: Apiaceae Family Common Name: Parsley or Carrot Scientific Name: Perideridia gairdneri (Hook. & Arn.) Mathias Common Name: Gairdner's yampah, Western yampah, False caraway Species Code: PEGA3 Ecotype: Paradise Creek drainage near Pullman, Washington. General Distribution: Western North America from British Columbia east to Saskatchewan and south to New Mexico. Mean annual precipitation range is 14-24 inches (USDA NRCS 2006). In eastern Washington it is usually found in open mesic meadows and open forest. Wetland status is FACU (US Fish and Wildlife Service 1988). Propagation Goal: Plants Propagation Method: Seed Product Type: Container (plug) Time To Grow: 2 Years Propagule Collection: Fruit is a schizocarp. Seed is collected in September or early October when the inflorescence is dry and the seeds are brown in color. Seed can be stripped from the inflorescence or the entire inflorescence can be clipped from the plant. Harvested seed is stored in paper bags at room temperature until cleaned. 400,000 seeds/lb (USDA NRCS 2006). Propagule Processing: The inflorescence is rubbed by hand to free the seed, then cleaned with an air column separator. Clean seed is stored in controlled conditions at 40 degrees Fahrenheit and 40% relative humidity. Pre-Planting Treatments: Unpublished data from trials conducted at the Pullman Plant Materials Center revealed that no germination occurred without stratification or with 30 days stratification. 60 days of cold, moist stratification resulted in 38% germination. -

Loch Lomond Button-Celery)

Natural Diversity Data Base 2003). The Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge populations have been monitored annually since 1992 (J. Silveira in litt. 2000). One additional occurrence of C. hooveri in Merced County is on private land (the Bert Crane Ranch) that is protected from development by a conservation easement (J. Silveira in litt. 2000). We funded a status survey for Chamaesyce hooveri and other vernal pool plants in 1986 and 1987 (Stone et al. 1988), resulting in 10 new occurrences. We and the California Department of Fish and Game jointly funded an ecological study of the Vina Plains Preserve pools, which was conducted by faculty from California State University, Chico (Alexander and Schlising 1997). Independent surveys conducted by Joseph Silveira led to discovery of the Merced and Glenn county occurrences (J. Silveira in litt. 2000). Private landowners also have contributed to conservation of this species. One pool in Tehama County was fenced by the property owner in the late 1980s, to exclude livestock (Stone et al. 1988). 3. ERYNGIUM CONSTANCEI (LOCH LOMOND BUTTON-CELERY) a. Description and Taxonomy Taxonomy.—Loch Lomond button-celery, specifically known as Eryngium constancei (Sheikh 1983), is a member of the carrot family (Apiaceae). This species was only recently described and therefore has no history of name changes. The common name was derived from the type locality, Loch Lomond, which is in Lake County (Sheikh 1983). Other common names for this species are Loch Lomond coyote-thistle (Skinner and Pavlik 1994) and Constance’s coyote-thistle (Smith et al. 1980). Description and Identification.—Certain features are common to species of the genus Eryngium. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

Colorado Report

Sedgwick Logan Larimer Weld Moffat Jackson Phillips Routt Morgan Grand Boulder Yuma Rio Blanco Gilpin Adams Washington Clear Denver Arapahoe Eagle Creek Garfield Summit Jefferson Douglas Elbert Kit Carson Pitkin Lake Park Mesa Teller Delta Lincoln Cheyenne El Paso Gunnison Chaffee Fremont Kiowa Montrose Crowley Ouray Saguache Custer Pueblo San Miguel Hinsdale Prowers Bent Otero Dolores San Juan Huerfano Mineral Alamosa Rio Grande Montezuma Las Animas Baca La Plata Costilla Archuleta Conejos Excellent 2 Sedgwick Good 26 Logan Larimer Weld Moffat Jackson Phillips Routt Fair 28 Morgan Poor 22 Grand Boulder Yuma Rio Blanco V. Poor 22 Gilpin Adams Washington Clear Denver Arapahoe Eagle Creek Garfield Summit Jefferson Douglas Elbert Kit Carson Pitkin Lake Park Mesa Teller Delta Lincoln Cheyenne El Paso Gunnison Chaffee Fremont Kiowa Montrose Crowley Ouray Saguache Custer Pueblo San Miguel Hinsdale Prowers Bent Otero Dolores San Juan Huerfano Mineral Alamosa Rio Grande Montezuma Las Animas Baca La Plata Costilla Archuleta Conejos Colorado – Southeast District • Estimating 25% abandonment, which takes harvested acreage down to about 205,000 acres • 15 bu/ac yields on field that are kept • Only expecting ~3.2 million bushels here ~275k acres in district 15% of acres in district Fremont Crowley Custer Pueblo Prowers Bent Otero 105k Huerfano acres Las Animas Baca 145k acres Colorado – East Central District Phillips 225k acres Yuma Adams Washington Arapahoe 220k acres Douglas Elbert Kit Carson 135k acres Lincoln Cheyenne El Paso 120k acres Kiowa 155k acres 67% of acres in district ~1.25 million acres in district • Just starting to get notices of abandonment here, range 2-25%, currently only have it at 7% across district (harvested acres would be 1.15 million) • 12 stops made here to take tiller counts. -

Indian History- Time Line

Indian history- time line Some facts about the Paleo Indians: about 10,000 years ago, they traveled in groups of 10-20 people; Paleo Indians were hunters and gathers; They hunted herds of big game; Their clothes were animal skins; They had no bow or arrows (used 9,500 years later) at that time; Their shelter was over hanging rock (shelves); Their life span was about 30 years. When large animals left the area, they hunted sheep, deer antelope, bison and some elk. They settled in the nearby drainages and ate their hunted animals. Ute Indian were a nomadic group. They lived in Wiki ups and then teepees. In 1500’s, the Spanish colonized the New Mexico and Colorado area and brought in the horses. In 1776, Dominquez and Escalante used the Spanish trails, followed by Mountain Men and finally the Mormons in 1840. The Spanish traders wanted the dark pelts of beaver. After the beavers were trapped out, the Utes offered brain tanned buckskin (deer and mountain sheep) which was very soft and good for trade. These buckskin hides became very popular as riding breeches and outdoor garments. The Tanning process: The Utes cleaned the hides starting with flesh side up, and staked the hides to dry. The hair, fat and extra meat was scraped off repeatly. When dried, they rubbed both sides with a paste was made out of the animal brains, then place the hides over smoke fires to dry and cut down on the shrinkage. The process took about 8 hours per skin. When starvation set in, the Utes would eat their clothing.