Education of the Deaf in the Sixties: a Description and Critique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(IP REPORT) - October 1, 2020 Through October 31, 2020 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - October 1, 2020 through October 31, 2020 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 6 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 73 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 141 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 85 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 83 EDUCATION 30 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 12 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 179 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 22 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 578 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 103 RELIGION 13 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 61 Total Story Count 1386 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 124:43:49 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 628 Fresh Air FA 36 Morning Edition ME 500 TED Radio Hour TED 14 Weekend Edition WE 208 Total Story Count 1386 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 124:43:49 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 10/24/2020 0:03:56 Employees Who Work At Multiple Nursing Homes May Have Helped Spread The Coronavirus Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 10/23/2020 0:04:16 Hockey Broadcaster Mike 'Doc' Emrick Signs Off Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 10/23/2020 0:03:47 A Chile Referendum To Reform Pinochet-Era Constitution Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 10/23/2020 0:03:39 Trump -

GLAAD Where We Are on TV (2020-2021)

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 Where We Are on TV 2020 – 2021 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 4 From the office of Sarah Kate Ellis 7 Methodology 8 Executive Summary 10 Summary of Broadcast Findings 14 Summary of Cable Findings 17 Summary of Streaming Findings 20 Gender Representation 22 Race & Ethnicity 24 Representation of Black Characters 26 Representation of Latinx Characters 28 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 30 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 32 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 34 Representation of Transgender Characters 37 Representation in Alternative Programming 38 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 40 Representation on Daytime, Kids and Family 41 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 43 Glossary of Terms 44 About GLAAD 45 Acknowledgements 3 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis For 25 years, GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, of our work every day. GLAAD and Proctor & Gamble gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters released the results of the first LGBTQ Inclusion in on television. This year marks the sixteenth study since Advertising and Media survey last summer. Our findings expanding that focus into what is now our Where We Are prove that seeing LGBTQ characters in media drives on TV (WWATV) report. Much has changed for the LGBTQ greater acceptance of the community, respondents who community in that time, when our first edition counted only had been exposed to LGBTQ images in media within 12 series regular LGBTQ characters across both broadcast the previous three months reported significantly higher and cable, a small fraction of what that number is today. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Sound Editing For A Nonfiction Or Reality Program (Single Or Multi-Camera) All In: The Fight For Democracy All In: The Fight For Democracy follows Stacey Abrams’s journey alongside those at the forefront of the battle against injustice. From the country’s founding to today, this film delves into the insidious issue of voter suppression - a threat to the basic rights of every American citizen. Allen v. Farrow Episode 2 As Farrow and Allen cement their professional legacy as a Hollywood power couple, their once close-knit family is torn apart by the startling revelation of Woody's relationship with Mia's college-aged daughter, Soon-Yi. Dylan details the abuse allegations that ignited decades of backlash, and changed her life forever. Amend: The Fight For America Promise Immigrants have long put their hope in America, but intolerant policies, racism and shocking violence have frequently trampled their dreams. American Masters Mae West: Dirty Blonde Rebel, seductress, writer, producer and sexual icon -- Mae West challenged the morality of our country over a career spanning eight decades. With creative and economic powers unheard of for a female entertainer in the 1930s, she “climbed the ladder of success wrong by wrong.” American Murder: The Family Next Door Using raw, firsthand footage, this documentary examines the disappearance of Shanann Watts and her children, and the terrible events that followed. American Oz (American Experience) Explore the life of L. Frank Baum, author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. By 1900, Baum had spent his life in pursuit of success. -

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH STREET ACADEMY NC 21ST CENTURY ALTERNATIVE MO 21ST CENTURY COMMUNITY SCHOOLHOUSE OR 21ST CENTURY CYBER CS PA 270 HOPKINS ALC MN 270 HOPKINS ALT. PRG - OFF CAMPUS MN 270 HOPKINS HS ALC MN 271 KENNEDY ALC MN 271 MINDQUEST OLL MN 271 SHAPE ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA HS ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA SR. ALC MN 276-MINNETONKA RSR-ALC MN 279 IS ALC MN 279 SR HI ALC MN 281 HIGHVIEW ALC MN 281 ROBBINSDALE TASC ALC MN 281 WINNETKA LEARNING CTR. ALC MN 3-6 PROG (BNTFL HIGH) UT 3-6 PROG (CLRFLD HIGH) UT 3-B DENTENTION CENTER ID 622 ALT MID./HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 FARMINGTON HS. MN 917 HASTINGS HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 LAKEVILLE SR. HIGH MN 917 SIBLEY HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 SIMLEY HIGH SCHOOL SP. ED. MN A & M CONS H S TX A B SHEPARD HIGH SCH (CAMPUS) IL A C E ALTER TX A C FLORA HIGH SC A C JONES HIGH SCHOOL TX A C REYNOLDS HIGH NC A CROSBY KENNETT SR HIGH NH A E P TX A G WEST BLACK HILLS HIGH SCHOOL WA A I M TX A I M S CTR H S TX A J MOORE ACAD TX A L BROWN HIGH NC A L P H A CAMPUS TX A L P H A CAMPUS TX A MACEO SMITH H S TX A P FATHEREE VOC TECH SCHOOL MS A. C. E. AZ A. C. E. S. CT A. CRAWFORD MOSLEY HIGH SCHOOL FL A. D. HARRIS HIGH SCHOOL FL A. -

Iffls G E M M E U . IW EB17J8S3

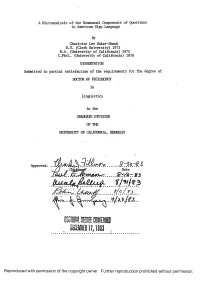

A M icroanalysis o f the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language By Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk B.S. (Clark U niversity) 1972 M.A. O Jniversity o f C alifornia) 1975 C.Phil. (University of California) 1978 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Approved: Date IfflSGEMMEU . IWEB17J8S3 \ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A Microanalysis of the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language C opyright © 1983 by Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements .................................................................................. v ii List of Figures .................................................................................... x List of Photographs ..................................... x ii List of Drawings .......................................................................................x i i i Transcription Conventions .................................................... iv C hapter I - EXPERIENCES OF DEAF PEOPLE IN A HEARING WORLD ................................................. 1 1.0 Formal education of deaf people: historical review •• 1 1.1 -

Schools and Libraries 2Q2016 Funding Year 2015 Authorizations - 4Q2015 Page 1 of 182

Universal Service Administrative Company Appendix SL27 Schools and Libraries 2Q2016 Funding Year 2015 Authorizations - 4Q2015 Page 1 of 182 Applicant Name City State Primary Authorized 100 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE NORTH LAS VEGAS NV 11,790.32 4-J SCHOOL GILLETTE WY 207.11 A + ACADEMY CHARTER SCHOOL DALLAS TX 19,122.48 A + CHILDRENS ACADEMY COMMUNITY SCHOOL COLUMBUS OH 377.16 A B C UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT CERRITOS CA 308,684.37 A SPECIAL PLACE SANTA ROSA CA 8,500.00 A W BEATTIE AVTS DISTRICT ALLISON PARK PA 1,189.32 A+ ARTS ACADEMY COLUMBUS OH 20,277.16 A-C COMM UNIT SCHOOL DIST 262 ASHLAND IL 518.70 A.C.E. CHARTER HIGH SCHOOL TUCSON AZ 1,530.03 A.M. STORY INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL PALESTINE TX 34,799.00 AAA ACADEMY BLUE ISLAND IL 39,446.55 AACL CHARTER SCHOOL COLORADO SPRINGS CO 10,848.59 AAS-ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE SAN DIEGO CA 2,785.82 ABBOTSFORD SCHOOL DISTRICT ABBOTSFORD WI 6,526.23 ABERDEEN PUBLIC LIBRARY ABERDEEN ID 2,291.04 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 5 ABERDEEN WA 54,176.10 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 58 ABERDEEN ID 8,059.20 ABERDEEN SCHOOL DISTRICT 6-1 ABERDEEN SD 13,560.24 ABIDING SAVIOR LUTHERAN SCHOOL SAINT LOUIS MO 320.70 ABINGTON COMMUNITY LIBRARY CLARKS SUMMIT PA 208.81 ABINGTON SCHOOL DISTRICT ABINGTON PA 19,710.58 ABINGTON SCHOOL DISTRICT ABINGTON MA 573.19 ABSAROKEE SCHOOL DIST 52-52 C ABSAROKEE MT 16,093.91 ABSECON PUBLIC LIBRARY ABSECON NJ 372.26 ABUNDANT LIFE CHRISTIAN ACAD MARGATE FL 1,524.99 ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DEL CENTRO RAMON RIVERA SAN SEBASTIAN PR 1,057.75 PEREZ ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DEL NORESTE AGUADILLA PR 5,434.40 ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DEL NORTE ARECIBO PR 7,157.47 ACADEMIA ADVENTISTA DR. -

Accreditation Columbus State Is Tobacco Free

Columbus State Community College makes every effort to educational opportunities for veterans, individuals with disabilities, present accurate/current information at the time of this publi- women, and minorities. cation. However, the college reserves the right to make changes to information contained herein as needed. The online college Reasonable Accommodations (Ref. Policy 3-41) http:// catalog is deemed the official college catalog and is maintained www.cscc.edu/_resources/media/about/pdf/3-41.pdf at www.cscc.edu. For academic planning purposes, the online catalog should be consulted to verify the currency of the infor- It is Columbus State Community College policy to make reasonable mation presented herein. accommodations, which will provide otherwise qualified applicants, employees, and students with disabilities equal access to participate Accreditation in opportunities, programs, and services offered by the college. Columbus State Community College is accredited by The Higher Students in need of an accommodation due to a physical, mental Learning Commission, Member-North Central Assn. (NCA), 230 or learning disability can contact Disability Services, Eibling Hall S. LaSalle St., Suite 7-500, Chicago, IL 60604-1413, (312) 263- 101 or 614-287-2570 (VOICE/TTY). On the Delaware Campus, 0456 or (800) 621-7440, www.ncahlc.org. see Student Services in Moeller Hall or call (740)203-8345. Nondiscrimination Policy (Ref. Policy 3-42, 3-43) http:// www.cscc.edu/_resources/media/about/pdf/3-42.pdf http://www.cscc.edu/_resources/media/about/pdf/3-43. Columbus State is Tobacco Free pdf Columbus State Community College strives to enhance the general Columbus State Community College is committed to maintaining health and wellbeing of its students, faculty, staff and visitors. -

To Download The

Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTE VEDRA October 1, 2020 RNot yourecor average newspaper, not your average reader Volume 51, No. 48 der 75 cents PonteVedraRecorder.com IN FULL SWING Nease graduate Tyler McCumber hits a shot during the Corales Puntacana Championship last weekend. McCumber had a career-best finish with a total 271 to place second at the tournament. Read more in Sports on page 28. Photo provided by PGA TOUR/Andy Lyons with Getty Images What’s Available NOW On Ponte Vedra Recorder · October 1, 2020 CONNECTIONS 11 INSIDE: CHECK IT OUT! The Recorder’s Entertainment “Movie: The Forty-Year-Old “The Haunting of Bly Manor” “Deaf U” This coming-of-age documentary series Version” “The School Nurse Files” The latest chapter in “The Haunting” Radha (writer/director Radha Blank) is a from executive producers Eric Evangelista, From South Korea comes this comedy anthology series from creators Mike down-on-her-luck playwright desperate Shannon Evangelista, Nyle DiMarco and series about a young nurse with an Flanagan and Trevor Macy delves into Brandon Panaligan takes an unfiltered to pen her breakthrough script before apparent ability to chase ghosts, who is the mystery behind a gothic manor with turning 40. When she seemingly blows her look at a tight-knit group of students at hired to work at a high school beset by Connections centuries of dark secrets of love and loss Gallaudet University, a renowned private last opportunity, she reinvents herself as mysterious secrets and occurrences. Yu-mi and the people who inhabit it. Henry college for the deaf and hard of hearing a rapper and then finds herself vacillating Jung, Joo-Hyuk Nam, Dylan J. -

Black D/Deaf Students Thriving Within the Margins Lissa Denielle Stapleton Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2014 The unexpected talented tenth: Black d/Deaf students thriving within the margins Lissa Denielle Stapleton Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Higher Education Administration Commons, and the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Stapleton, Lissa Denielle, "The unexpected talented tenth: Black d/Deaf students thriving within the margins" (2014). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13891. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13891 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The unexpected talented tenth: Black d/Deaf students thriving within the margins by Lissa Denielle Stapleton A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Education (Educational Leadership) Program of Study Committee: Natasha Croom, Major Professor Katherine Bruna Nancy Evans William Garrow Patricia Leigh Robert Reason Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2014 Copyright © Lissa Denielle Stapleton, 2014. All rights reserved ii DEDICATION To my ancestors and all the Unexpected Talented Tenth who answered the call and persisted- We are the hope, aspiration, and promise. I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, and I have remained faithful. -

Incorrect FY 2007 Rals

Incorrect FY 2007 RALs BEN Applicant Name Form 471# FRN 169 QUABOAG REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 556295 1534362 659 ST LOUIS SCHOOL 566347 1562649 909 LINCOLN-SUDBURY REG HIGH SCH 556945 1535775 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 577322 1596793 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 577462 1609374 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 577462 1610182 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 578901 1601734 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 581604 1611687 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 581859 1611705 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 582212 1613176 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 582212 1613250 1365 HARBOR SCHOOLS INC. 582212 1613361 1490 NOTRE DAME ACADEMY 580885 1609297 1606 BOSTON RENAISSANCE CHTR SCH 570331 1574288 1606 BOSTON RENAISSANCE CHTR SCH 570331 1574293 1606 BOSTON RENAISSANCE CHTR SCH 570331 1574298 1606 BOSTON RENAISSANCE CHTR SCH 570331 1574303 1606 BOSTON RENAISSANCE CHTR SCH 570331 1574306 1606 BOSTON RENAISSANCE CHTR SCH 570331 1574309 1611 CATHEDRAL HIGH SCHOOL 552910 1527275 1611 CATHEDRAL HIGH SCHOOL 554323 1529217 1611 CATHEDRAL HIGH SCHOOL 557890 1538161 1611 CATHEDRAL HIGH SCHOOL 557890 1538198 1611 CATHEDRAL HIGH SCHOOL 564536 1557424 1661 SMITH LEADERSHIP ACADEMY CHARTER PUBLIC SCHOOL 583050 1624890 1661 SMITH LEADERSHIP ACADEMY CHARTER PUBLIC SCHOOL 583050 1624933 1661 SMITH LEADERSHIP ACADEMY CHARTER PUBLIC SCHOOL 583050 1625064 1838 BENJAMIN BANNEKER CHTR SCH 562799 1552547 2013 SOLOMON SCHECHTER DAY SCHOOL OF GREATER BOSTON 552463 1524441 2110 GERMAINE LAWRENCE INC. 555802 1533170 2110 GERMAINE LAWRENCE INC. 555802 1535559 2110 GERMAINE LAWRENCE INC. 555802 1584027 2512 CRYSTAL SPRINGS SCHOOL A PROGRAM -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Main Title Design All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Allen v. Farrow The Amber Ruffin Show The American Barbecue Showdown Archer Aunty Donna's Big Ol' House Of Fun B Positive Between The World And Me Biggie: I Got A Story To Tell A Black Lady Sketch Show Black Narcissus Blood Of Zeus The Boy From Medellín Bridgerton Cake Calls Clarice Coastal Elites Coyote Crack: Cocaine, Corruption & Conspiracy The Crime Of The Century Crime Scene: The Vanishing At The Cecil Hotel Cursed Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! The Daily Show With Trevor Noah Presents: Remembering RBG – A Nation Ugly Cries With Desi Lydic Dance Dreams: Hot Chocolate Nutcracker David Byrne's American Utopia Deaf U Death To 2020 Delilah Dolly Parton's Christmas On The Square Dota: Dragon's Blood Earth To Ned Equal The Equalizer Exterminate All The Brutes The Falcon And The Winter Soldier Fargo Firefly Lane The Flight Attendant 40 Years A Prisoner Full Bloom Generation Hustle Genius: Aretha Girls5eva Going To Pot: The High & Low Of It The Good Lord Bird Grand Army The Great North The Haunting Of Bly Manor Heaven's Gate: The Cult Of Cults Helstrom High On The Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America Hip Hop Uncovered History Of Swear Words Hold These Truths With Dan Crenshaw Home Economics Hysterical I'll Be Gone In The Dark Immigration Nation The Irregulars Jupiter's Legacy The Lady And The Dale The Last Narc Lenox Hill The Liberator Little Voice Love Fraud Lovecraft Country Mariah Carey's Magical Christmas Special Marvel 616 Mayans M.C. -

Can You Hear Me Later and Believe Me Now? Behavioral Law and Economics of Chronic Repeated Ambient Acoustic Pollution Causing Noise-Induced (Hidden) Hearing Loss

RLSJ0V29-HUANG-POORE-TO-PRINT.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 11/8/20 3:39 PM CAN YOU HEAR ME LATER AND BELIEVE ME NOW? BEHAVIORAL LAW AND ECONOMICS OF CHRONIC REPEATED AMBIENT ACOUSTIC POLLUTION CAUSING NOISE-INDUCED (HIDDEN) HEARING LOSS ∗ ∗∗ PETER H. HUANG AND KELLY J. POORE ABSTRACT This Article analyzes the public health issues of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss (“NIHL”) and Noise-Induced Hidden Hearing Loss (“NIHHL”) due to Chronic Repeated Ambient Acoustic Pollution (“CRAAP”). This Article examines the clinical and empirical medical data about NIHL and NIHHL and its normative implications. It applies behavioral law and economics and information economics to advance legal policies to reduce CRAAP. Finally, this Article advocates changing individual and social attitudes about deafness and hearing loss to raise ∗ Professor and Laurence W. DeMuth Chair of Business Law, University of Colorado Law School; J.D., Stanford Law School; Ph.D., Harvard University; A.B., Princeton University. Thanks to the University of Colorado Law School for summer research support. Thanks for helpful comments, discussions, and questions to Jane Thompson and audience members of the 2019 Midwestern Behavioral Law and Economics Association annual meeting at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law and the John F. Scarpa Center for Law and Entrepreneurship, and the 2020 annual business law conference of the Pacific Southwest Academy of Legal Studies in Business. Thanks to my co-Author for inspiring my interests in the d/Deaf community and culture. Both authors thank Emma Cunningham and Emily Monroe from the editorial board for their diligence, efficiency, exemplary professionalism, hard work, and edits on this Article.