Black D/Deaf Students Thriving Within the Margins Lissa Denielle Stapleton Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deaf American Historiography, Past, Present, and Future

CRITICAL DISABILITY DISCOURSES/ 109 DISCOURS CRITIQUES DANS LE CHAMP DU HANDICAP 7 The Story of Mr. And Mrs. Deaf: Deaf American Historiography, Past, Present, and Future Haley Gienow-McConnella aDepartment of History, York University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a review of deaf American historiography, and proposes that future scholarship would benefit from a synthesis of historical biography and critical analysis. In recent deaf historical scholarship there exists a tendency to privilege the study of the Deaf community and deaf institutions as a whole over the study of the individuals who comprise the community and populate the institutions. This paper argues that the inclusion of diverse deaf figures is an essential component to the future of deaf history. However, historians should not lapse in to straight-forward biography in the vein of their eighteenth and nineteenth-century predecessors. They must use these stories purposefully to advance larger discussions about the history of the deaf and of the United States. The Deaf community has never been monolithic, and in order to fully realize ‘deaf’ as a useful category of historical analysis, the definition of which deaf stories are worth telling must broaden. Biography, when coupled with critical historical analysis, can enrich and diversify deaf American historiography. Key Words Deaf history; historiography; disability history; biography; American; identity. THE STORY OF MR. AND MRS. DEAF 110 L'histoire de «M et Mme Sourde »: l'historiographie des personnes Sourdes dans le passé, le présent et l'avenir Résumé Le présent article offre un résumé de l'historiographie de la surdité aux États-Unis, et propose que dans le futur, la recherche bénéficierait d'une synthèse de la biographie historique et d’une analyse critique. -

Pigeonhole Podcast 18

Pigeonhole Episode 18 [bright ambient music] Introduction CHORUS OF VOICES: Pigeonholed, pigeonhole, pigeonhole, pigeonhole, pigeonhole, pigeonhole, pigeonhole, pigeonhole. [mellow ambient music plays] CHERYL: Since this is a story-based podcast, I don’t have a lot of interviews. This interview is a rebroadcast from the old podcast from 2017 recorded by Skype. It’s been edited just a bit for length. Talila “TL” Lewis has been named a White House Champion of Change and was also named one of the Top 30 Thinkers Under 30 by Pacific Standard in 2015. Talila is an attorney-organizer and visiting professor at Rochester Institute of Technology and National Technical Institute for the Deaf who founded and works with the all-volunteer organization HEARD, which stands for Helping Educate to Advance the Rights of Deaf communities. HEARD focuses on correcting and preventing deaf wrongful convictions, ending abuse of incarcerated people with disabilities; decreasing recidivism rates for deaf returned citizens; and increasing representation of deaf people in professions that can counter mass incarceration and end the attendant school to prison pipeline. Talila created the only national database of deaf incarcerated individuals. This is something the jails and prisons aren’t tracking themselves. Talila also maintains contact with hundreds of deaf incarcerated individuals. TL also leads intersectional campaigns that advance the rights of multiply-marginalized people, including the #DeafInPrison Campaign, the Deaf Prisoner Phone Justice Campaign, and the American Civil Liberties Union’s “Know Your Deaf Rights” Campaign. The show page and transcript will have a link to the syllabus TL created and uses for a class called Disability Justice in the Age of Mass Incarceration. -

Social Justice, Audism, and the D/Deaf: Rethinking Linguistic and Cultural Differences

Social Justice, Audism, and the d/Deaf: Rethinking Linguistic and Cultural 65 Differences Timothy Reagan Contents Introduction ..................................................................................... 1480 An Introduction to the DEAF-WORLD ....................................................... 1482 Language .................................................................................... 1483 Cultural Identity ............................................................................. 1485 Behavioral Norms and Practices ............................................................ 1487 Endogamy ................................................................................... 1487 Cultural Artifacts ............................................................................ 1488 In-Group Historical Knowledge ............................................................ 1488 Voluntary Social Organizations ............................................................. 1489 Humor ....................................................................................... 1489 Literary and Artistic Tradition .............................................................. 1490 Becoming Deaf .............................................................................. 1494 The Duality of Deaf Identity ................................................................ 1494 Epistemology and the DEAF-WORLD ........................................................ 1495 Social Justice and the DEAF-WORLD ....................................................... -

Ontario's Seniors Strategy

Email: [email protected] Website: seniorpridenetwork.com July 10, 2019 Ontario’s Seniors Strategy Consultation Seniors Policy and Programs Division Ministry for Seniors and Accessibility 777 Bay Street, Suite 601C Toronto, ON M7A 2J4 The Senior Pride Network (Toronto) welcomes this opportunity to provide input into the consultation on Ontario’s Seniors Strategy. The Senior Pride Network (Toronto) is an association of individuals and organizations committed to promoting appropriate services and a positive, caring environment for elders, seniors and older persons who identify as 2 Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, transsexual, queer, intersex and other (2SLGBTTQI+). We envision a series of communities of 2SLGBTTQI+ elders, seniors and older persons that are respectful, affirming, supportive, safe and healthy. The Senior Pride Network (Toronto) asserts and advocates for the human, economic, social and cultural rights of 2SLGBTTQI+ elders, seniors and older persons. We seek to eradicate all forms of oppression including homophobia, heterosexism, lesbophobia, transphobia, biphobia, sexism, cissexism, racism, antisemitism, settler colonialism, xenophobia, islamophobia, ableism and ageism. We demand the right of all 2SLGBTTQI+ elders, seniors and older persons to live their lives free from discrimination, harassment, reprisal, bullying, intimidation, victimization, stigmatization, silencing, being marginalized or being made invisible. 2SLGBTTQI+ Elders, Seniors and Older Persons and Ontario’s Seniors Strategy 2SLGBTTQI+ elders, seniors and older persons face a number of issues that have impacted their lived experiences and may have negatively affected their mental or physical health, their financial and housing circumstances and their overall social well-being. Gaining an understanding of those issues and positively addressing them are necessary to developing and implementing an inclusive and effective Ontario’s Seniors Strategy. -

Attitudes Towards Individuals Who Are Deaf and Hard of Hearing

ffff Attitudes towards individuals who are deaf and hard of hearing Introduction For individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing (DHH), negative attitudes from DHH and hearing individuals can serve as a barrier to healthy social and emotional development22, social integration17, and academic and career success 19. Societal attitudes toward individuals who are deaf is an important research topic because: Attitudes toward DHH individuals are critical aspects of integration into social and academic activities.23 Knowledge of attitudes toward individuals who are DHH contributes to understanding and positive interactions between hearing and DHH individuals.15 What does the research tell us about attitudes toward people who are DHH? Researchers have assessed attitudes toward individuals with disabilities, as well as deaf individuals specifically. Some findings include: Negative attitudes toward individuals with disabilities have existed throughout history and still exist today.8 There are differences in attitudes toward people who are deaf compared to people with other disabilities.16 Hearing people have been found to hold more negative attitudes toward individuals with an intellectual disability than toward individuals who are deaf.7,10 The relationship between attitudes and expectations “Attitudes toward Attitudes can be conveyed through expectations; people tend people with to internalize and fulfill the expectations others have of them.6 disabilities represent Parental expectations strongly influence their deaf childrens’ an individual’s -

Books About Deaf Culture

Info to Go Books about Deaf Culture 1 Books about Deaf Culture The printing of this publication was supported by federal funding. This publication shall not imply approval or acceptance by the U.S. Department of Education of the findings, conclusions, or recommendations herein. Gallaudet University is an equal opportunity employer/educational institution, and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, religion, age, hearing status, disability, covered veteran status, marital status, personal appearance, sexual orientation, family responsibilities, matriculation, political affiliation, source of income, place of business or residence, pregnancy, childbirth, or any other unlawful basis. 2 Books about Deaf Culture There are many books about the culture, language, and experiences that bind deaf people together. A selection is listed in alphabetical order below. Each entry includes a citation and a brief description of the book. The names of deaf authors appear in boldface type. Abrams, C. (1996). The silents. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. A hearing daughter portrays growing up in a close Jewish family with deaf parents during the Depression and World War II. When her mother begins to also lose her sight, the family and community join in the effort to help both parents remain vital and contributing members. 272 pages. Albronda, M. (1980). Douglas Tilden: Portrait of a deaf sculptor. Silver Spring, MD: T. J. Publishers. This biography portrays the artistic talent of this California-born deaf sculptor. Includes 59 photographs and illustrations. 144 pages. Axelrod, C. (2006). And the journey begins. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press. Cyril Axelrod was born into an Orthodox Jewish family and is now deaf and blind. -

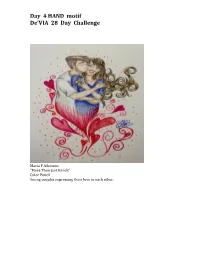

Day 4 HAND Motif De'via 28 Day Challenge

Day 4 HAND motif De’VIA 28 Day Challenge Maria F Atkinson "More Than Just Hands" Color Pencil Young couples expressing their love to each other. Kat Brockway Title: Opening up Made on ipad Art Studio app Description: using hands, we push out the blockage in our way and OPEN UP to many doors of opportunities! David Call Two DeVIA Mothers Color pencil Description: This artwork was inspired by Frida Kahlo's Two Fridas painting. First generation DeVIA mother Betty G Miller and second generation DeVIA mother Nancy Rourke bonded by same DeVIA blood. Betty G Miller colors are based on Betty G Miller's Birth of a Deaf Mother painting and Nancy Rourke colors based on her trademark primary color paintings. It is a challenge for me to capture the essence of both artists' painting style and transfer to this artwork! Patti Durr Hand doodle Description: it has a few De'VIA motifs within it (black and white doodles fill in of a 5 finger hand and wrist) Patti Durr HandEye solidarity fists linocut w/ ink on paper 8 1/2 x 5 1/2 Description: color pix of two cards - one is red on gold ish paper and one is black on white paper - HandEye solidarity fist with streaks around it and the word OBEY at bottom. Bethany Hall "Kiss My Fist" 8.5 by 11 drawing paper, blue pencil Description: Every now and then the hearing community puts their own expectations or opinions on me- such as telling me I don't need an interpreter, indirectly telling me to use TC, expecting me to my voice, relieved that I can lip-read (regardless of the fact when I tell them it's not 100% reliable), giving me attitudes of audism, telling me I'm not deaf (hate that) and acting as if my hearing aid is a miracle. -

University of Idaho Digital Collections

Cd'A .: . - gE"I:;:!."':Vow,,@J.;„',.- human - .,:-,:;;;.:: .': .: Since M!rriott rights:::: ..:;:;::::.:::—::,::.:;:,:'' --' '::,' -'',-- . ''. -;;-,',:,;:'.: took over, there have march,:,::: ':;::",.':::. ', been pay cuts, posi- endorsed tion cuts and Moscow human rights numerous student anti- corn laints. grouP suPPorts APril /Issociated Students —. University of Idaho P racism march. —Karlene Cameron Senate Idaho gives Zinser a red-carpet reception rejects Hundreds flock to meet the Ul's new SBA $115,000 woman funding By ANGELA CURTIS Managing Editor By VIVIANE GILBERT Staff Writer onths of press leaks, M scandalous organiza- he Student Bar Association tional charts and a much- will receive $5,000 less than criticized presidential search they requested from the ASUI were forgotten Thursday. Senate, as a result of the ASUI fis- Elisabeth Zinser came to cal year 1990 budget approved town. Wednesday night. Hundreds of celebrants The SBA, a law student organi- flocked to the University of zation, will receive $3,100 next Idaho Thursday to welcome year —the same amount they the woman many of them had were allotted this year. But this personally invited to accept the year the group requested $8,100 presidency here. Zinser said from the Senate. she had received cards, notes Mike Gotch, senate finance and telegrams encouraging her chairman, said additional funds to become the university's 14th were not given to SBA because president. the association funded some "I feel all have truly HEARTY HANDSHAKE. On her way to a Thursday afternoon reception held in her honor, groups the senate felt were "inap- you fund." embraced me," Zinser said. President-Designate Elisabeth Zinser is greeted in the SUB by members of the Moscow Chamber of propriate to The SBA funds about a dozen "All I can say is it beats being Commerce, Zinser accepted the Idaho Board of Education's job offer Tuesday. -

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH

School State 11TH STREET ALTERNATIVE SCHOOL KY 12TH STREET ACADEMY NC 21ST CENTURY ALTERNATIVE MO 21ST CENTURY COMMUNITY SCHOOLHOUSE OR 21ST CENTURY CYBER CS PA 270 HOPKINS ALC MN 270 HOPKINS ALT. PRG - OFF CAMPUS MN 270 HOPKINS HS ALC MN 271 KENNEDY ALC MN 271 MINDQUEST OLL MN 271 SHAPE ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA HS ALC MN 276 MINNETONKA SR. ALC MN 276-MINNETONKA RSR-ALC MN 279 IS ALC MN 279 SR HI ALC MN 281 HIGHVIEW ALC MN 281 ROBBINSDALE TASC ALC MN 281 WINNETKA LEARNING CTR. ALC MN 3-6 PROG (BNTFL HIGH) UT 3-6 PROG (CLRFLD HIGH) UT 3-B DENTENTION CENTER ID 622 ALT MID./HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 FARMINGTON HS. MN 917 HASTINGS HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 LAKEVILLE SR. HIGH MN 917 SIBLEY HIGH SCHOOL MN 917 SIMLEY HIGH SCHOOL SP. ED. MN A & M CONS H S TX A B SHEPARD HIGH SCH (CAMPUS) IL A C E ALTER TX A C FLORA HIGH SC A C JONES HIGH SCHOOL TX A C REYNOLDS HIGH NC A CROSBY KENNETT SR HIGH NH A E P TX A G WEST BLACK HILLS HIGH SCHOOL WA A I M TX A I M S CTR H S TX A J MOORE ACAD TX A L BROWN HIGH NC A L P H A CAMPUS TX A L P H A CAMPUS TX A MACEO SMITH H S TX A P FATHEREE VOC TECH SCHOOL MS A. C. E. AZ A. C. E. S. CT A. CRAWFORD MOSLEY HIGH SCHOOL FL A. D. HARRIS HIGH SCHOOL FL A. -

From the Invisible Hand to Joined Hands

1 From the Invisible Hand to Joined Hands But for the personal computing movement, there would be no Apple. Nearly all of the technical aspects associated with personal computing—small computers, microproces- sors, keyboard-based interfaces, individual usability—were available in 1972. As early as 1969, Honeywell had released the H316 “Kitchen Computer” priced at $10,600 in the Neiman Marcus catalog, and in 1971 John Blankenbaker had intro- duced the Kenbak-1 priced at $750 and Steve Wozniak and Bill Fernandez had built their Cream Soda Computer—so named because they drank Cragmont cream soda as they built the computer with chips discarded by local semicon- ductor companies. But the idea of using computers as personalized tools that augmented the autonomy of individuals only took root because of the efforts of hobbyists and engineers.1 According to some, the first shot of the personal computing movement was in 1966 when Steven Gray founded the Amateur Com- puting Society and published a newsletter for hobbyists, which became a model for hobbyist clubs around the coun- try. At that time, large firms such as IBM or DEC were dedi- cated to a centralized conception of computing in which the mainframe was tended by a priesthood of managers, engi- neers, and operators who prevented users from touching and working with the computer. Their focus effectively blinkered them to the other possibilities—that fans and tinkerers 1 Chapter 1 should have access and that they could in fact make a bundle by serving that market. As one historian of computing noted, “The most rigid rule was that no one should be able to touch or tamper with the machine itself. -

The Deaf Do Not Beg: Making the Case for Citizenship, 1880-1956

The Deaf Do Not Beg: Making the Case for Citizenship, 1880-1956 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Octavian Elijah Robinson Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Susan Hartmann, Advisor Paula Baker Susan Burch Judy Tzu-Chun Wu Copyright by Octavian Elijah Robinson 2012 Abstract This dissertation examines deaf people’s anxieties about their place in American society and the political economy from 1880 to 1956. My study highlights how deaf people sought to place themselves within mainstream society through their activism to protect and advance their status as citizen-workers. Their activism centered on campaigns against peddling. Those campaigns sought to protect the public image of deaf people as worker-citizens while protecting their language and cultural community. The rhetoric surrounding impostorism and peddling reveals ableist attitudes; anxieties about the oral method supplanting sign language based education for the deaf; fears and insecurities about deaf people’s place in the American economy; class consciousness; and efforts to achieve full social citizenship. Deaf people’s notion of equal citizenship was that of white male citizenship with full access to economic opportunities. Their idea of citizenship extended to the legal and social right to employment and economic self-sufficiency. This is a historical account of the deaf community’s campaign during the late nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century to promote deaf people within American society as equal citizens and to improve their access to economic opportunities. -

Copyright by Jennifer Nichole Asenas 2007

Copyright by Jennifer Nichole Asenas 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Jennifer Nichole Asenas Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Past as Rhetorical Resource for Resistance: Enabling and Constraining Memories of the Black Freedom Struggle in Eyes on the Prize Committee: Dana L. Cloud, Supervisor Larry Browning Barry Brummett Richard Cherwitz Martha Norkunas The Past as Rhetorical Resource for Resistance: Enabling and Constraining Memories of the Black Freedom Struggle in Eyes on the Prize by Jennifer Nichole Asenas, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August, 2007 Dedication For Jeff and Marc Acknowledgements This dissertation is the product of many kind souls with brilliant minds who agreed to helped me throughout this process. I would like to thank my advisor, Dana Cloud, for being a living example of a scholar who makes a difference. I would also like to thank my committee members: Barry Brummett, Richard Cherwitz, Martha Norkunas, and Larry Browning for contributing to this project in integral and important ways. You have all influenced the way that I think about rhetoric and research. Thank you Angela Aguayo, Kristen Hoerl, and Lisa Foster for blazing trails. Jaime Wright, your inner strength is surpassed only by your kindness. Johanna Hartelius, you have reminded me how special it is to be loved. Lisa Perks, you have been a neighbor in all ways. Amanda Davis, your ability to speak truth to power is inspiring.